Baseball… the Unfair Sport © 2012 Ted Frank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

Illegal, but Not Against the Rules Commentary by Shanin Specter OK

August 9, 2007 Illegal, but not against the rules Commentary By Shanin Specter OK, so Barry Bonds did it. What should we think? Many believe Bonds used steroids to break Hank Aaron's home run record, but that's only a beginning point for analysis. Here's the polestar: As legendary manager John McGraw said about baseball, "The main idea is to win. " What circumscribes this creed? Only the rules of baseball. If a runner stealing second knows the fielder's tag beat his hand to the base, but the umpire calls him safe, should he stay on the base? Yes. If an outfielder traps a fly ball, can he play it as if he caught it? Yes. The uninitiated might consider this to be fraud or immoral. But some deception is part of the game. This conduct is appropriate simply because it's not forbidden by the rules. Baseball isn't golf. There's no honor code. Yankee Alex Rodriguez's foiling a pop-up catch by yelling may have been bush league, but umpires imposed no punishment. Typical retaliation would be a pitch in the ribs in the next at-bat - assault and battery in the eyes of the law, but just part of the game of baseball. Baseball has a well-oiled response to cheating. Pitchers who scuff the ball are tossed out of that game and maybe the next one, too. Players who cork bats face a similar fate. Anyone thought to be engaged in game- fixing is banned for life. No court of public opinion or law has overturned that sentence. -

Jan-29-2021-Digital

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 64, No. 2 Friday, Jan. 29, 2021 $4.00 Innovative Products Win Top Awards Four special inventions 2021 Winners are tremendous advances for game of baseball. Best Of Show By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Editor/Collegiate Baseball Awarded By Collegiate Baseball F n u io n t c a t REENSBORO, N.C. — Four i v o o n n a n innovative products at the recent l I i t y American Baseball Coaches G Association Convention virtual trade show were awarded Best of Show B u certificates by Collegiate Baseball. i l y t t nd i T v o i Now in its 22 year, the Best of Show t L a a e r s t C awards encompass a wide variety of concepts and applications that are new to baseball. They must have been introduced to baseball during the past year. The committee closely examined each nomination that was submitted. A number of superb inventions just missed being named winners as 147 exhibitors showed their merchandise at SUPERB PROTECTION — Truletic batting gloves, with input from two hand surgeons, are a breakthrough in protection for hamate bone fractures as well 2021 ABCA Virtual Convention See PROTECTIVE , Page 2 as shielding the back, lower half of the hand with a hard plastic plate. Phase 1B Rollout Impacts Frontline Essential Workers Coaches Now Can Receive COVID-19 Vaccine CDC policy allows 19 protocols to be determined on a conference-by-conference basis,” coaches to receive said Keilitz. -

The Brooklyn Nine DISCUSSION GUIDE

The Brooklyn Nine DISCUSSION GUIDE “A wonderful baseball book that is more than the sum of its parts.” The Horn Book About the Book 1845: Felix Schneider cheers the New York 1945: Kat Flint becomes a star in the All- Knickerbockers as they play Three-Out, All-Out. American Girls Baseball League. 1864: Union soldier Louis Schneider plays 1957: Ten-year-old Jimmy Flint deals with bullies, baseball between battles in the Civil War. Sputnik, and the Dodgers leaving Brooklyn. 1893: Arnold Schneider meets his hero King 1981: Michael Flint pitches a perfect game in a Kelly, one of professional baseball's first big stars. Little League game at Prospect Park. 1908: Walter Snider sneaks a black pitcher into 2002: Snider Flint researches a bat that belonged the Majors by pretending he's Native American. to one of Brooklyn's greatest baseball players. 1926: Numbers wiz Frankie Snider cons a con One family, nine generations. with the help of a fellow Brooklyn Robins fan. One city, nine innings of baseball. Make a Timeline Questions for Discussion Create a timeline with pictures of First Inning: Play Ball important events from baseball and American history that Who was the first of your ancestors to come to America? correspond to the eras in each of Where is your family from? Could you have left your home to the nine innings in The Brooklyn make a new life in a foreign land? Nine. Use these dates, and add some from your own research. How is baseball different today from the way it was played by Felix and the New York Knickerbockers in 1845? First Inning: 1845 Felix's dreams are derailed by the injury he suffers during the 1835 – First Great Fire in Great Fire of 1845, but he resolves to succeed anyway. -

The Bloody Nose

THE BLOODY NOSE AND OTHER STORIES A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Emily D. Dressler May, 2008 THE BLOODY NOSE AND OTHER STORIES Emily D. Dressler Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________ ___________________________ Advisor Department Chair Mr. Robert Pope Dr. Diana Reep __________________________ ___________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the College Dr. Mary Biddinger Dr. Ronald F. Levant __________________________ __________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Robert Miltner Dr. George R. Newkome ___________________________ ___________________________ Faculty Reader Date Dr. Alan Ambrisco ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following stories have previously appeared in the following publications: “The Drought,” Barn Owl Review #1; “The Winters,” akros review vol. 35; “An Old Sock and a Handful of Rocks,” akros review vol. 34 and “Flint’s Fire,” akros review vol. 34. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PART I. HELEN……………………………………………………………………………….1 The Bloody Nose……………………………………………………………………......2 Butterscotch………………………………………………………………………….....17 Makeup…………………………………………………………………………………29 The Magic Show………………………………………………………………………..44 The Drought…………………………………………………………………………….65 Important and Cold……………………………………………………………………..77 Someone Else…………………………………………………………………………...89 II. SHORTS…………………………………………………………………………….100 An Old Sock and a Handful of Rocks………………………………………………….101 Adagio………………………………………………………………………………….105 -

ENCYCLOPEDIA of BASEBALL

T HE CHILD’ S WORLD® ENCYCLOPEDIA of BASEBALL VOLUME 3: REGGIE JACKSON THROUGH OUTFIELDER T HE CHILD’ S WORLD® ENCYCLOPEDIA of BASEBALL VOLUME 3: REGGIE JACKSON THROUGH OUTFIELDER By James Buckley, Jr., David Fischer, Jim Gigliotti, and Ted Keith KEY TO SYMBOLS Throughout The Child’s World® Encyclopedia of Baseball, you’ll see these symbols. They’ll give you a quick clue pointing to each entry’s general subject area. Active Baseball Hall of Miscellaneous Ballpark Team player word or Fame phrase Published in the United States of America by The Child’s World® 1980 Lookout Drive, Mankato, MN 56003-1705 800-599-READ • www.childsworld.com www.childsworld.com ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Child’s World®: Mary Berendes, Publishing Director Produced by Shoreline Publishing Group LLC President / Editorial Director: James Buckley, Jr. Cover Design: Kathleen Petelinsek, The Design Lab Interior Design: Tom Carling, carlingdesign.com Assistant Editors: Jim Gigliotti, Zach Spear Cover Photo Credits: Getty Images (main); National Baseball Hall of Fame Library (inset) Interior Photo Credits: AP/Wide World: 5, 8, 9, 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 32, 33, 36, 37, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 50, 52, 56, 57, 59, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 70, 72, 74, 75, 78, 79, 80, 83, 75; Corbis: 18, 22, 37, 39; Focus on Baseball: 7t, 10, 11, 29, 34, 35, 38, 40, 41, 49, 51, 55, 58, 67, 69, 71, 76, 81; Getty Images: 54; iStock: 31, 53; Al Messerschmidt: 12, 48; National Baseball Hall of Fame Library: 6, 7b, 28, 36, 68; Shoreline Publishing Group: 13, 19, 25, 60. -

Nats Win at Last, Backing Good Pitching with Power to Trample

Farm,and Garden ■*•«**,Financial News __Junior Star_ 101(1^ Jgtflf jgptiTlg_Stomps _ WASHINGTON, I). C., APIIIL 21, 1946. :_■__ ___ Nats Win at Last, Backing Good Pitching With Power to Trample Yankees, 7-3 ★ ★ _____# ★ ★ ★ ★ ose or Assault Shines in Wood, Armed Lands Philadelphia at 'Graw By FRANCIS E. STANN --- 4 Heath's Benching Follows Simmons-Bonura Pattern AT LEAST ONE GOT BY —By Gib Crockett Test The benching of Outfielder Jeff Heath by the Nationals after Texas Ace Passes Derby less than a week of play is not without precedent. Heath, you re- Spence's Homer member, was acquired for one purpose—to hit that long, extra-base In Finish at Jamaica wallop for Washington. But so were A1 Simmons and Zeke Bonura Sizzling some years ago. Marine Simmons had been one of the greatest right- Heads Rips by Favored Hampden, Victory hand sluggers m the history of the American Slashing On to Win League. For that matter, iie may have been In Stretch, Goes 2-Length the absolute greatest. Critics generally rated By the Associated Press licked a $22,600 pay check for Simmons and Rogers Hornsby of the National f up 1 lis him a bank as 14-Hit NEW YORK, 20.—The Texas day's work, giving the two modern Attack League best of times. April ■oil of $30,100 for the year and The Milwaukee Pole was over the hill when terror from the wide open spaces,,’ 47,350 for his two seasons. Clark Griffith got him, but he still was a home Leonard, stretch-burning Assault, sizzled to a He’ll take the train ride to the run threat. -

April 2021 Auction Prices Realized

APRIL 2021 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot # Name 1933-36 Zeenut PCL Joe DeMaggio (DiMaggio)(Batting) with Coupon PSA 5 EX 1 Final Price: Pass 1951 Bowman #305 Willie Mays PSA 8 NM/MT 2 Final Price: $209,225.46 1951 Bowman #1 Whitey Ford PSA 8 NM/MT 3 Final Price: $15,500.46 1951 Bowman Near Complete Set (318/324) All PSA 8 or Better #10 on PSA Set Registry 4 Final Price: $48,140.97 1952 Topps #333 Pee Wee Reese PSA 9 MINT 5 Final Price: $62,882.52 1952 Topps #311 Mickey Mantle PSA 2 GOOD 6 Final Price: $66,027.63 1953 Topps #82 Mickey Mantle PSA 7 NM 7 Final Price: $24,080.94 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron PSA 8 NM-MT 8 Final Price: $62,455.71 1959 Topps #514 Bob Gibson PSA 9 MINT 9 Final Price: $36,761.01 1969 Topps #260 Reggie Jackson PSA 9 MINT 10 Final Price: $66,027.63 1972 Topps #79 Red Sox Rookies Garman/Cooper/Fisk PSA 10 GEM MT 11 Final Price: $24,670.11 1968 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Wax Box Series 1 BBCE 12 Final Price: $96,732.12 1975 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Rack Box with Brett/Yount RCs and Many Stars Showing BBCE 13 Final Price: $104,882.10 1957 Topps #138 John Unitas PSA 8.5 NM-MT+ 14 Final Price: $38,273.91 1965 Topps #122 Joe Namath PSA 8 NM-MT 15 Final Price: $52,985.94 16 1981 Topps #216 Joe Montana PSA 10 GEM MINT Final Price: $70,418.73 2000 Bowman Chrome #236 Tom Brady PSA 10 GEM MINT 17 Final Price: $17,676.33 WITHDRAWN 18 Final Price: W/D 1986 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan PSA 10 GEM MINT 19 Final Price: $421,428.75 1980 Topps Bird / Erving / Johnson PSA 9 MINT 20 Final Price: $43,195.14 1986-87 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan -

Coach's Packet

MARLBOROUGH YOUTH BASEBALL ASSOCIATION MYBA 2012 COACHES PACKET 1 Fielding GROUND BALLS If you've ever been to a little league practice before, chances are that you've seen a variation on the following: the coach lines his players up, hits the ball to them, and the ones with some existing skill or innate talent do a good job... while the new player or the less talented athlete struggles. The coach tells them to "get in front of the ball," to "get their glove down," and to "keep the ball in front of them." And that's about the extent of it. Maybe this improves over the course of the season. Unfortunately, this is all too often not the case - instead, the lesser fielders get dropped into the outfield in an effort to minimize their liability to the team. As a result, they get less practice reps than the infielders, and if anything, the disparity between the skill level of infield and outfield widens further. Now, we’re not suggesting that you should place your weakest fielder at shortstop. What we’re suggesting is that you, as the coach, need to make sure that you give all of your players the tools they need in order to succeed. The best way you can do this is by emphasizing - and then consistently teaching - the fundamentals of baseball fielding. How many times have you seen a young player run after a pop-up with their glove extended as if they were expecting the ball to change direction in mid air and fall into the glove? Have you ever seen a player setup for a grounder by placing his/her glove firmly on the ground and then look shocked that the ball skipping by didn't go where it was supposed to? Why, because most kids are used to parents, coaches, and friends rolling or throwing the ball directly at them. -

GLOVE DON't BUY a BASEBALL GLOVE! Softball Players Require

GLOVE DON’T BUY A BASEBALL GLOVE! Softball players require gloves that are slightly longer in length and deeper in the pocket than baseball gloves to help field the bigger ball. Keep these things in mind when buying a softball glove: • Youth gloves are smaller to help kids maintain control (avoid the urge to buy a bigger glove that she'll “grow into”) • Leather gloves are the preferred material • Buy a glove that is comfortable on the hand applicable to the size of the girl Division Glove Size Tee-Ball & 6U 9 – 11 inches 8U 10 – 11 inches 10U 10 ½ – 12 inches 12U/14U/16U 11 ½ – 13 inches CLEATS Baseball and/or softball shoes have one unique feature to look for that makes them different than soccer shoes: the toe cleat. Baseball shoes have a toe cleat at the very tip of the shoe that soccer shoes do not have. This helps players get better traction in quick starts where sudden movement occurs. EGSA requires all players to wear baseball/softball shoes with plastic cleats; however soccer shoes with plastic cleats may be worn. Metal cleats are not allowed by EGSA. SLIDING SHORTS Sliding shorts are worn underneath uniform shorts or pants and can give players the confidence to slide without the fear of getting injured. Although they are not required, EGSA recommends them for the 8U division and above. Sliding shorts can be purchased with heavy padding or little padding. KNEE GUARDS (sliders) Sliders provide extra protection when sliding and fielding. They are optional however EGSA recommends them for all divisions. -

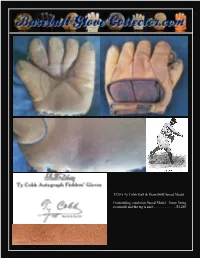

1920'S Ty Cobb Stall & Dean 8045 Speed

= 1920’s Ty Cobb Stall & Dean 8045 Speed Model Outstanding condition Speed Model. Inner lining is smooth and the tag is nice……...………...$5,250 1924-28 Babe Pinelli Ken Wel 550 Glove One of the more desirable Ken Wel NEVERIP models, this example features extremely supple leather inside and out. It’s all original. Can’t find any flaws in this one. The stampings are super decent and visible. This glove is in fantastic condition and feels great on the hand…….…………………………………………………………………..……….$500 1960’s Stall & Dean 7612 Basemitt = Just perfect. Gem mint. Never used and still retains its original shape………………………………………………...$95 1929-37 Eddie Farrell Spalding EF Glove Check out the unique web and finger attachments. This high-end glove is soft and supple with some wear (not holes) to the lining. Satisfaction guaranteed….………………………………………………………………………………..$550 1929 Walter Lutzke D&M G74 Glove Draper Maynard G74 Walter Lutzke model. Overall condition is good. Soft leather and good stamping. Does have some separations and some inside liner issues……………………………………………………………………..…$350 = 1926 Christy Mathewson Goldsmith M Glove Outstanding condition Model M originally from the Barry Halper Collection. Considered by many to be the nicest Matty example in the hobby....……………...$5,250 = 1960 Eddie Mathews Rawlings EM Heart of the Hide Glove Extremely rare Eddie Mathews Heart of the Hide model. You don’t see this one very often…………………………..$95 1925 Thomas E. Wilson 650 Glove This is rarity - top of the line model from the 1925 Thomas E. Wilson catalog. This large “Bull Dog Treated Horsehide” model glove shows wear and use with cracking to the leather in many areas. -

Baseball Devices

The War Amps For Your Information Tel.: 1 877 622-2472 Fax: 1 855 860-5595 [email protected] Baseball Devices for Arm Amputees Throwing Devices he COBRA by TRS can replicate natural, Tinstinctive throwing skills. It is fully adjustable for ball release and throwing angles to optimize control and maximize ball speed for accurate throws. COBRA The COBRA is designed specifically for baseballs and is appropriate for either left or right below elbow amputees aged 12 and up. Batting Devices The Power Swing Ring by TRS is a great aid for batting for the arm amputee. The ring, which screws directly into the bottom of the bat, is grasped with Power Swing Ring the player’s prosthesis (such as a split-hook or ADEPT device), while the sound hand grasps the handle of the bat. When the player swings the bat, the swivel action of the ring simulates the wrist “break” or “rollover” necessary in batting. Using the Power Swing Ring allows the player to swing hard and smoothly with the control and power of both arms. The Grand Slam by TRS provides a powerful, smooth, two-handed swing with an easy on/off design. The Grand Slam slips onto all bats with one inch diameter handles creating proper hand placement. The high performance flexible coupling (with braided steel reinforcing) duplicates anatomical “wrist break.” The Grand Slam will not damage the bat. Prosthetic Limbs and Devices Prosthetic Grand Slam Custom Batting Devices These batting devices (right) were constructed to meet the individual needs of the amputees who own them.