Kansas Ornithological Society BULLETIN PUBLISHED QUARTERLY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crows and Ravens Wildlife Notes

12. Crows & Ravens Crows and ravens belong to the large family Corvidae, along with more than 200 other species including jays, nutcrackers and magpies. These less-than-melodious birds, you may be surprised to learn, are classified as songbirds. raven American Crow insects, grain, fruit, the eggs and young of other birds, Crows are some of the most conspicuous and best known organic garbage and just about anything that they can find of all birds. They are intelligent, wary and adapt well to or overpower. Crows also feed on the carcasses of winter – human activity. As with most other wildlife species, crows and road-killed animals. are considered to have “good” points and “bad” ones— value judgements made strictly by humans. They are found Crows have extremely keen senses of sight and hearing. in all 50 states and parts of Canada and Mexico. They are wary and usually post sentries while they feed. Sentry birds watch for danger, ready to alert the feeding birds with a sharp alarm caw. Once aloft, crows fly at 25 Biology to 30 mph. If a strong tail wind is present, they can hit 60 Also known as the common crow, an adult American mph. These skillful fliers have a large repertoire of moves crow weighs about 20 ounces. Its body length is 15 to 18 designed to throw off airborne predators. inches and its wings span up to three feet. Both males Crows are relatively gregarious. Throughout most of the and females are black from their beaks to the tips of their year, they flock in groups ranging from family units to tails. -

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge BIRD LIST

Merrritt Island National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service P.O. Box 2683 Titusville, FL 32781 http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Merritt_Island 321/861 0669 Visitor Center Merritt Island U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 1 800/344 WILD National Wildlife Refuge March 2019 Bird List photo: James Lyon Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, located just Seasonal Occurrences east of Titusville, shares a common boundary with the SP - Spring - March, April, May John F. Kennedy Space Center. Its coastal location, SU - Summer - June, July, August tropic-like climate, and wide variety of habitat types FA - Fall - September, October, November contribute to Merritt Island’s diverse bird population. WN - Winter - December, January, February The Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee lists 521 species of birds statewide. To date, 359 You may see some species outside the seasons indicated species have been identified on the refuge. on this checklist. This phenomenon is quite common for many birds. However, the checklist is designed to Of special interest are breeding populations of Bald indicate the general trend of migration and seasonal Eagles, Brown Pelicans, Roseate Spoonbills, Reddish abundance for each species and, therefore, does not Egrets, and Mottled Ducks. Spectacular migrations account for unusual occurrences. of passerine birds, especially warblers, occur during spring and fall. In winter tens of thousands of Abundance Designation waterfowl may be seen. Eight species of herons and C – Common - These birds are present in large egrets are commonly observed year-round. numbers, are widespread, and should be seen if you look in the correct habitat. Tips on Birding A good field guide and binoculars provide the basic U – Uncommon - These birds are present, but because tools useful in the observation and identification of of their low numbers, behavior, habitat, or distribution, birds. -

A Soft Spot for Crows by David Shaw

Read this article. Then answer the questions that follow. A Soft Spot for Crows by David Shaw 1 Crows are probably the most ignored bird species in North America. They are often fiewed as pests, or at the very least as untrustworthy. Even the term for a group of crows, a "murder," hardly creates positive associations. Yet these birds are everywhere. They are as common, and perhaps as despised, as pigeons. But there a lot more to the crow family than most people think. It Runs in the Family 2 The United States has four resident species of crows. The most abundant and widespread is the American crow, which lives across most of the lower 48 and southern Canada. 3 The slightly smaller northwestern crow has a nasal voice and occurs only along the coasts of the Pacific Northwest from Puget Sound to south central Alaska. 4 The fish crow is similar in size and voice to the northwestern crow but lives on the Atlantic coast and in the lower Mississippi River region. 5 And finally there is the Hawaiian crow, which, as the name implies, occurs only in Hawaii, and there only in a small area of forest. (A fifth species, the tamaulipas, dwells in northern Mexico and is sometimes seen in Texas' lower Rio Grande valley. But it doesn't appear to breed north of the border, so it's not considered a true U.S. resident.) 6 I don't remember my first sighting of a crow, though I suspect I was very young. Even after I'd developed as a birder, I'm still not sure when I first put that tick on my list. -

Hellmayr's 'Catalogue of Birds of the Americas'

Vol.1935 LII] J RecentLiterature. 105 RECENT LITERATURE. Hellmayr's 'Catalogue of Birds of the Americas.'--The long awaitedseventh part of this notable work• has appeared, covering the families Corvidae to Sylviidae in almostthe orderof the A. O. U. 'Check-List,'with the neotropicalfamily Zeledo- niidae betweenthe Turdidae and Sylviidae. The volume follows exactly the style of its predecessors,with the same abundanceof foot notes discussingcharacters and relationshipsof many of the forms, and will, we are sure, prove of the sameimpor- tance to systematic studentsof the avifauna of the Americas. It brings the subject up to July 1, 1932. It is impossiblein the space at our disposalto discussall of the innovations in systematic arrangement and in nomenclaturewhich are presentedby Dr. Hel]mayr in these pages and we shall have •o be content, for the most part, with a comparison of his findingsin regard to North American Birds with those of the A. O. U. reittee, as expressedin the fourth edition of the 'Check-List.' The author is very conservativein his treatment of genera six of those recognized in the 'Check-List' beingmerged with others--Penthestesand Baeolophuswith Parus; Telmatodyteswith Cistothorus;Nahnus with Troglodyles;Arceuthornis with Turdus; Corthyliowith Regulus--going back in every case but one to the treatment of the first edition of the 'Check-List,' in 1886, so doesthe pendulumswing from one ex- treme to the other and back again! Generic division is largely a matter of personal opinion and while there is much to be said in favor of someof Dr. Hellmayr's actions it seemsa pity that two well-markedgroups like the Long- and Short-billed Marsh Wrens should have to be merged simply becauseof the discovery of a more or less intermediate speciesin South America. -

Reference Bird List

Species R SP SU FA WI Notes:_________________________________________________ John G. and Susan H. Shrikes Laniidae Loggerhead Shrike (P) U U U U Vireo Vireonidae DuPuis, Jr. ________________________________________________________ White-eyed Vireo (P) C C C C Blue-headed Vireo (W) C Wildlife and Jays & Crows Corvidae American Crow (P) C C C C ________________________________________________________ Fish Crow (P) C C C C Environmental Blue Jay (P) C C C C Red-Cockaded Woodpeckers Swallows Hirundinidae ________________________________________________________ Purple Martin (S) U U Species R SP SU FA WI Area Northern Rough-winged Swallow (W) O O O O Parulidae Barn Swallow (P) O O O O Wood-Warblers Prothonotary Warbler (S) R R Tree Swallow (W) C ________________________________________________________ Pine Warbler (P) C C C C Wrens Troglodytidae Palm Warbler (W) C C C C Carolina Wren (P) C C C C Prairie Warbler (P) C C C C House Wren (W) U Yellow-rumped Warbler (W) C C C ________________________________________________________ Kinglets Regulidae Yellow-throated Warbler (W) C C Ruby-crowned Kinglet (W) C Blue-Gray Gnatcatcher (W) C C C C Black-throated Green Warbler (W) O We are interested in your sightings. Please share your American Redstart (W) O observations with us. Thrushes Turdidae Black and White Warbler (W) C C Eastern Bluebird (P) R R R R Enjoy your visit! American Robin (W) C Northern Parula (W) R Common Yellowthroat (P) C C C C Mockingbirds & Thrashers Mimidae Gray Catbird (W) C C Ovenbird (W) O O Additional contact information: -

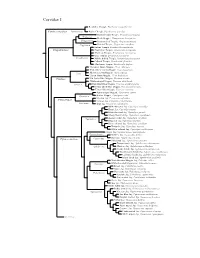

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Birds of the Conecticut River Watershed

www.fws.gov Birds of the Conecticut River Watershed (from the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge Final Action Plan and Environmental Impact Statement, October, 1995, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Hadley, MA) Common name Scientific name Waterfowl Tundra swan Cygnus columbianus Mute swan Cygnus olor Canada goose Branta canadensis Mallard Anas platyrhynchos American black duck Anas rubripes Gadwall Anas strepera Green-winged teal Anas crecca American wigeon Anas americana Northern pintail Anas pintail Northern shoveler Anas acuta Blue-winged teal Anas discors Ruddy duck Oxyura jamaicensis Wood duck Aix sponsa Canvasback Aythya valisineria Redhead Aythya americana Ring-necked duck Aythya collaris Greater scaup Aythya marila Lesser scaup Aythya affinis White-winged scoter Melanitta fusca Surf Scoter Melanitta perspicillata Black scoter Melanitta nigra Oldsquaw Clangula hyemalis Common goldeneye Bucephala clangula Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Common merganser Mergus merganser Red-breasted merganser Mergus serrator Hooded merganser Lophodytes cucullatus Shorebirds Piping plover Charadrius melodus Semipalmated plover Charadrius semipalmatus Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Black-bellied plover Pluvialis squatarola Lesser golden plover Pluvialis dominica Willet Catoptrophorus semipalmatus Greater yellowlegs Tringa melanoleuca Lesser yellowlegs Tringa flavipes Solitary sandpiper Tringa solitaria Spotted sandpiper Actitis macularia Common snipe Gallinago gallinago Semipalmated sandpiper Callidris pusilla Silvio O. Conte National Fish -

Ravens, Crows, and Blackbirds at This Time of Year, Our Present Western Culture Is Consumed with Scary, Creepy, and Mysterious

BirdWalk Newsletter 10.29.2017 Walks Conducted by Perry Nugent Newsletter Written by Jayne J. Matney “Not Really Pitch Black” Photo by Guenter Webber Ravens, Crows, and Blackbirds At this time of year, our present western culture is consumed with scary, creepy, and mysterious. Sometimes the blackbirds, ravens, and crows are used to pull this off. Black may suggest to some people thoughts of evil or death. Of course, it didn’t help their “non-benevolent cause” when Edgar Allan Poe wrote “The Raven”. These birds get a bad rap and then at other times are hardly acknowledged or noticed. At first glance, black birds, such as crows, red-winged blackbirds, ravens, and grackle seem like uninteresting, drab birds. However, if you look at them closely, and study them more thoroughly, they may surprise you. First of all, the black you see has an iridescence to it which shows many glossy colors reflecting off from the sunlight at different angles. Secondly, there are some interesting facts about them that most people would not know. In ancient culture and Native American culture, the black birds represented “good passage and protection” or a benevolent message or happy tiding. Other writings indicate that black birds of any type represent a higher intelligence, higher Photo by Guenter Weber understanding of the universe, secrets, and mysteries. Unable to gage whether they have a higher understanding, researchers have shown that the crow certainly is a good example of high intelligence. They have been known to be one of the few animals that can perceive and solve complex problems and use tools or the environment to gain a solution to those problems. -

Wildlife Sightings J.N

Wildlife Sightings J.N. “Ding” Darling National Wildlife Refuge Includes Wildlife Drive and the Bailey Tract Week Ending Tuesday, May 14, 2019 Birds Mottled Duck Bald Eagle Prairie Warbler Magnificent Frigatebird Red-shouldered Hawk American Redstart Double-crested Cormorant Common Gallinule Northern Cardinal Anhinga Black-bellied Plover Common Grackle Brown Pelican Killdeer Great Blue Heron Black-necked Stilt Great Egret Willet Snowy Egret Dunlin Little Blue Heron Laughing Gull Tricolored Heron Eurasian Collared-Dove Reddish Egret Mourning Dove Green Heron Common Ground Dove Yellow-crowned Night-Heron Mangrove Cuckoo White Ibis Red-bellied Woodpecker Roseate Spoonbill Pileated Woodpecker Black Vulture Great Crested Flycatcher Turkey Vulture White-eyed Vireo Osprey Fish Crow Swallow-tailed Kite Carolina Wren Other Wildlife Northern Raccoon Florida Softshell Turtle Southern Toad Bobcat Florida Red-bellied Turtle Fiddler Crab Coyote Peninsula Cooter Mangrove Tree Crab River Otter Chicken Turtle Horseshoe Crab Diamondback Terrapin Marsh Rabbit Lubber Grasshopper Florida Box Turtle Nine-banded Armadillo Halloween Pennant Dragonfly Gopher Tortoise Virginia Opossum Giant Swallowtail Butterfly Green Iguana Florida Manatee Zebra Longwing Butterfly Brown Anole Lizard Bottlenose Dolphin Gulf Fritillary Butterfly Green Anole Lizard American Alligator White Peacock Butterfly Southern Five-lined Skink Yellow Rat Snake Monarch Butterfly Pig Frog Red Rat Snake/Corn Snake Mangrove Buckeye Butterfly Southern Leopard Frog Black Racer Snake Cloudless Sulphur Butterfly Greenhouse Frog Great Southern White Butterfly Ring-necked Snake Squirrel Tree Frog Blue Ceraunus Butterfly Florida Banded Water Snake Cuban Tree Frog Mangrove Salt Marsh Water Snake A special thanks to volunteer Ed Combs for compiling this list . -

Crow Fact Sheet

The Georgia Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Resources Division CROW FACT SHEET Crows are perhaps one of the most widely recognized birds in the northern latitudes crows exhibit migratory behavior but are United States. While some people view them favorably, others commonly year-long residents in Georgia. consider crows to be a nuisance. But whether liked or not, almost every one agrees that crows are adaptable, inquisitive and intelligent Crows are best classified as opportunistic omnivores. They consume birds. In fact, crows have become the subject of many myths and a wide variety of animal and vegetable foods including commercial legends. agricultural crops, fruits, nuts, insects, small mammals, salamanders, lizards, fledgling birds, bird eggs, carrion and human garbage. As Georgia is home to both the American Crow (Corvus with many other aspects of their life history, they exhibit great brachyrhyncos,), and the Fish Crow (Corvus ossifragus). Crows ingenuity in feeding including dropping hard-shelled nuts and other belong to the family Corvidae, which also includes ravens, jays and foods from great heights to break the items into consumable amounts. magpies. In addition to crows, Common Ravens (Corvus corax) are the only other large solid black birds occurring in Georgia. Ravens Crows begin nesting as early as late February and construct a new are found in extreme northern Georgia and are somewhat easily nest each year from sticks, twigs and other materials. Nests are often distinguished from crows by being much larger in size, having in the fork of a tree next to the trunk, 20 - 60 feet above the ground. -

Foraging Guilds of North American Birds

RESEARCH Foraging Guilds of North American Birds RICHARD M. DE GRAAF ABSTRACT / We propose a foraging guild classification for USDA Forest Service North American inland, coastal, and pelagic birds. This classi- Northeastern Forest Experiment Station fication uses a three-part identification for each guild--major University of Massachusetts food, feeding substrate, and foraging technique--to classify Amherst, Massachusetts 01003, USA 672 species of birds in both the breeding and nonbreeding seasons. We have attempted to group species that use similar resources in similar ways. Researchers have identified forag- NANCY G. TILGHMAN ing guilds generally by examining species distributions along USDA Forest Service one or more defined environmental axes. Such studies fre- Northeastern Forest Experiment Station quently result in species with several guild designations. While Warren, Pennsylvania 16365, USA the continuance of these studies is important, to accurately describe species' functional roles, managers need methods to STANLEY H. ANDERSON consider many species simultaneously when trying to deter- USDI Fish and Wildlife Service mine the impacts of habitat alteration. Thus, we present an Wyoming Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit avian foraging classification as a starting point for further dis- University of Wyoming cussion to aid those faced with the task of describing commu- Laramie, Wyoming 82071, USA nity effects of habitat change. Many approaches have been taken to describe bird Severinghaus's guilds were not all ba~cd on habitat feeding behavior. Comparisons between different studies, requirements, to question whether the indicator concept however, have been difficult because of differences in would be effective. terminology. We propose to establish a classification Thomas and others (1979) developed lists of species scheme for North American birds by using common by life form for each habitat and successional stage in the terminology based on major food type, substrate, and Blue Mountains of Oregon. -

Reproductive Success and Nest Depredation of the Florida Scrub-Jay

The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 119(2):162–169, 2007 REPRODUCTIVE SUCCESS AND NEST DEPREDATION OF THE FLORIDA SCRUB-JAY KATHLEEN E. FRANZREB1 ABSTRACT.—The Florida Scrub-jay (Aphelocoma coerulescens) is listed as a threatened species primarily because of habitat loss throughout much of its range. The Ocala National Forest in Florida contains one of three main subpopulations that must be stable or increasing before the species can be considered for removal from federal listing. However, little information is available on Florida Scrub-jay reproductive success or predation pressure on this forest. I used video cameras during 2002 and 2003 to identify nest predators and timing of predation events. The presence of the video system did not significantly affect the rate of nest abandonment. Thirteen nests were video-monitored of which one was abandoned, five experienced no predation, three were partially depredated, and four had total loss of nest contents. Snakes were responsible for more losses from predation than either mammals or birds. I monitored 195 other scrub-jay nests (no video-monitoring) and mea- sured the mean number of eggs, nestlings, and fledglings produced per breeding pair. No significant difference in reproductive success was detected between years or between year and helper status. Groups with helpers produced significantly more fledglings (0.5 per breeding pair) and had higher daily survival rates of nests in the egg stage, nestling stage, and the entire breeding season than groups lacking helpers. Received 15 July 2005. Accepted 7 October 2006. The Florida Scrub-jay (Aphelocoma coeru- ment, has led to an overall reduction in the lescens), federally listed as a threatened spe- amount of suitable scrub-jay habitat (Fitzpat- cies, occurs primarily on lands containing rick et al.