Downloaded/Printed from Heinonline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TT55 Controlling the Student

DOES YOUR SCHOOL TREAT STUDENTS DIFFERENTLY BASED ON THEIR IDENTITY CHARACTERISTICS? IF SO, IT’S TIME FOR A POLICY MAKEOVER. BY ALICE PETTWAY ILLUSTRATION BY REBECCA CLARKE An elementary student is sent home from her Texas school for wearing her hair in Afro puffs. • A Louisiana senior is forbidden to wear her tux to prom. • Three students in Pennsylvania are told they can’t use the bathrooms that match their gender identities. • An Illinois school releases a dress code flier that features two young women, one labeled “distracting” and “revealing,” the other “ladylike.” These are not isolated incidents. Similar stories preventing students from using gender-aligned have been reported in K–12 schools across the facilities send a similar message to students: United States, and more unfold every day. Nor “Your identity is a problem.” are they unrelated. Each situation was the result of a policy that treats students differently based A Culture of Respect on their identities. Thomas Aberli, former principal at Atherton High These policies may be based on good intentions School in Kentucky, says it’s important for school and rely on aspirational words like “respectable,” communities to consider what it really means—on “safe” or “appropriate.” But when, for example, a a practical level—to respect someone whose iden- hair policy disproportionately affects black students, tity is different from yours. Making sure school it reveals a harmful bias: the perception that natural policies are inclusive is a reflection of “how we black hair is none of those things. should treat one another in society,” he says. -

Taking the Kinks out of Your Hair and out of Your Mind: a Study on Black Hair and the Intersections of Race and Gender in the United States

Taking the Kinks Out of Your Hair and Out of Your Mind: A study on Black hair and the intersections of race and gender in the United States Tyler Berkeley Brewington Senior Comprehensive Thesis Urban and Environmental Policy Professor Bhavna Shamasunder Professor Robert Gottlieb April 19, 2013 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank God for giving me the strength to finish this project. All thanks goes to Him for allowing me to develop this project in ways that I didn’t even believe were possible. Secondly, I would like to thank my family and friends for supporting me through this process. Thank you for helping me edit my thesis, for sharing links about natural hair with me, and for connecting me with people to interview. Your love and support enable me to do everything – I am nothing without you! I would also like to thank Professor Shamasunder for being an amazing advisor and for always being there for me. Thank you for all of our office hours sessions, for your critical eye, and also for supporting this project from day one. I appreciate you so much! Also, I would like to thank Professor Gottlieb for helping me remain calm and thinking about the important body of work that I am producing. Thank you also for being such a great advisor to me throughout the years and for helping me find my passion! Finally, I would like to dedicate this report to “all the colored girls who considered going natural when the relaxer is enuf.” Thank you for inspiring me to go natural, this project would not have been possible without you. -

Lightspeed Magazine, Issue 87 (August 2017)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 87, August 2017 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial: August 2017 SCIENCE FICTION Tongue Ashok K. Banker The Sun God At Dawn, Rising From A Lotus Blossom Andrea Kail An Inflexible Truth Christopher East Swing Time Carrie Vaughn FANTASY East of Eden and Just a Bit South Ken Scholes The Shining Hills Susan Palwick A Citizen In Childhood’s Country Seanan McGuire Ink Bruce McAllister NOVELLA Steppin’ Razor Maurice Broaddus EXCERPTS The Clockwork Dynasty Daniel H. Wilson NONFICTION Book Reviews: August 2017 LaShawn M. Wanak TV Review: American Gods Joseph Allen Hill Interview: Annalee Newitz Christian A. Coleman AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Ashok K. Banker Susan Palwick Christopher East Bruce McAllister MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks About the Lightspeed Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2017 Lightspeed Magazine Cover by Reiko Murakami www.lightspeedmagazine.com Editorial: August 2017 John Joseph Adams | 756 words Welcome to issue eighty-seven of Lightspeed! Our cover this month is by Reiko Murakami, illustrating a new original science fiction short from Ashok K. Banker (“Tongue”). Our other original SF this month is from Christopher East (“An Inflexible Truth”). We also have SF reprints by Andrea Kail (“The Sun God At Dawn, Rising From A Lotus Blossom”) and Carrie Vaughn (“Swing Time”). Plus, we have original fantasy by Susan Palwick (“The Shining Hills”) and Bruce McAllister (“Ink”), and fantasy reprints by Ken Scholes (“East of Eden and Just a Bit South”) and Seanan McGuire (“A Citizen in Childhood’s Country”). All that, and of course we also have our book and media review columns, spotlights on our fantastic writers, and an interview with Annalee Newitz. -

DJ Song List by Song

A Case of You Joni Mitchell A Country Boy Can Survive Hank Williams, Jr. A Dios le Pido Juanes A Little Bit Me, a Little Bit You The Monkees A Little Party Never Killed Nobody (All We Got) Fergie, Q-Tip & GoonRock A Love Bizarre Sheila E. A Picture of Me (Without You) George Jones A Taste of Honey Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass A Ti Lo Que Te Duele La Senorita Dayana A Walk In the Forest Brian Crain A*s Like That Eminem A.M. Radio Everclear Aaron's Party (Come Get It) Aaron Carter ABC Jackson 5 Abilene George Hamilton IV About A Girl Nirvana About Last Night Vitamin C About Us Brook Hogan Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Abracadabra Sugar Ray Abraham, Martin and John Dillon Abriendo Caminos Diego Torres Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Nine Days Absolutely Not Deborah Cox Absynthe The Gits Accept My Sacrifice Suicidal Tendencies Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Ace In The Hole George Strait Ace Of Hearts Alan Jackson Achilles Last Stand Led Zeppelin Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Across The Lines Tracy Chapman Across the Universe The Beatles Across the Universe Fiona Apple Action [12" Version] Orange Krush Adams Family Theme The Hit Crew Adam's Song Blink-182 Add It Up Violent Femmes Addicted Ace Young Addicted Kelly Clarkson Addicted Saving Abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted Sisqó Addicted (Sultan & Ned Shepard Remix) [feat. Hadley] Serge Devant Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Addicted To You Avicii Adhesive Stone Temple Pilots Adia Sarah McLachlan Adíos Muchachos New 101 Strings Orchestra Adore Prince Adore You Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel -

Facial Mapping of Stratum Corneum Capacitance of Different Ethnic Groups

HAIR AND SCALP DAMAGE ASSOCIATED WITH ETHNIC HAIRSTYLING APPROACHES IN AFRICAN ALBINO WOMEN IN PRETORIA, SOUTH AFRICA M. Lategan, C. Moeletsi, B. Summers Photobiology Laboratory Sefako Makgatho University of Health Sciences, Pretoria, South Africa e-mail [email protected] Objective: African ethnic hair is closely-curled and as a result is often difficult to manage. It tangles easily and often breaks more readily than Caucasian hair, particularly when wet. The majority of styling options, to enhance manageability and improve appearance, involve either chemical relaxation, physical constraint (e.g. braiding) or close-cropping of the hair. Most of these approaches lead to hair or scalp damage unless well-controlled. For many people hair is one of the most important features to enhance personal beauty and self-confidence. Well-styled hair is seen as a status symbol, particularly in the black community of Southern Africa. This study was conducted to identify the hair styling approaches commonly used by Albino women of African ethnicity as well as the prevalence of hair and scalp damage which they experience. Methodology: A questionnaire was administered to a group of 17 Albino women aged between 24 and 60 who live in the Pretoria area. The questionnaire had previously been used in an ethically-approved, study on university students of African ethnicity, also in Pretoria. The questionnaire covered demographic details, hair styling approaches and related hair and scalp damage. Results: African Albino hair colour ranges from light blonde to red blonde. The most common washing frequency for the Albino group was every 2 weeks (47%), with 35% washing hair monthly. -

Sneak Peek Your Next Book Binge Starts Here

SNEAK PEEK YOUR NEXT BOOK BINGE STARTS HERE American Royals...............................................3 The Babysitters Coven ..................................38 Dear Martin ......................................................72 Gravemaidens ................................................103 Blood Heir .......................................................156 YOUR NEXT BOOK BINGE STARTS HERE SNEAK PEEK This is a work of fiction. All incidents and dialogue, and all characters with the exception of some well- known historical and public figures, are products of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Where real- life historical or public figures appear, the situations, incidents, and dialogues concerning those persons are fictional and are not intended to depict actual events or to change the fictional nature of the work. In all other respects, any resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental. Text copyright © 2019 by Katharine McGee and Alloy Entertainment Jacket art copyright © 2019 by Carolina Melis All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. AMERICAN Random House and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Visit us on the Web! GetUnderlined.com Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com ROYALS Produced by Alloy Entertainment alloyentertainment.com Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: McGee, Katharine, -

University Students' Attitudes Towards Body Hair and Hair Removal: An

Wayne State University DigitalCommons@WayneState Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2010 University Students' Attitudes Towards Body Hair And Hair Removal: An Exploration Of The ffecE ts Of Background Characteristics, Socialization, And Societal Pressures Bessie Rigakos Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Recommended Citation Rigakos, Bessie, "University Students' Attitudes Towards Body Hair And Hair Removal: An Exploration Of The Effects Of Background Characteristics, Socialization, And Societal Pressures" (2010). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 112. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. UNIVERSITY STUDENTS’ ATTITUDES TOWARDS BODY HAIR AND HAIR REMOVAL: AN EXPLORATION OF THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND CHARACTERISTICS, SOCIALIZATION, AND SOCIETAL PRESSURES by BESSIE N. RIGAKOS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2010 MAJOR: SOCIOLOGY Approved by: ____________________________ Advisor Date ____________________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY BESSIE N. RIGAKOS 2010 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION This is dedicated to future sociologists who embark on the dissertation process, "When you feel like giving up, remember why you held on for so long in the first place." ~ Unknown ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS If anyone was to ask, I would describe myself as a “product of Wayne State’s Sociology Department.” Through the years, there have been many people, such as my advisor, committee members, peers, and family members who have taught me about academia, sociology, and life in general. -

The Influence of Colorism and Hair Texture Bias on the Professional and Social Lives of Black Women Student Affairs Professionals

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 The nflueI nce of Colorism and Hair Texture Bias on the Professional and Social Lives of Black Women Student Affairs Professionals Rhea Monet Perkins Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Perkins, Rhea Monet, "The nflueI nce of Colorism and Hair Texture Bias on the Professional and Social Lives of Black Women Student Affairs Professionals" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2510. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2510 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF COLORISM AND HAIR TEXTURE BIAS ON THE PROFESSIONAL AND SOCIAL LIVES OF BLACK WOMEN STUDENT AFFAIRS PROFESSIONALS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Education by Rhea Monet Perkins B.S., Arizona State University, 2008 M.S., Florida International University, 2010 May 2015 This dissertation is for my nieces, C’Briannah, Cristina, Cayla and Crystal. C’Briannah and Cristina are the motivation behind my work with issues related to colorism. You both are beautiful, important, needed, and loved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am honored and excited to thank everyone who made the preparation and completion of this dissertation possible. -

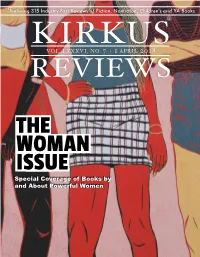

Special Coverage of Books by and About Powerful Women from the Editor’S Desk

Featuring 315 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVI, NO. 7 | 1 APRIL 2018 REVIEWS THE WOMAN ISSUE Special Coverage of Books by and About Powerful Women from the editor’s desk: Chairman Welcome to the Woman Issue HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY MEGAN LABRISE MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] Editor-in-Chief Kirkus believes in women’s worth and the power of words. So CLAIBORNE SMITH [email protected] when our critic calls Meg Wolitzer’s The Female Persuasion “the perfect Vice President of Marketing SARAH KALINA feminist blockbuster for our times,” take note: The use of a word asso- [email protected] ciated with big-budget action movies targeting men isn’t accidental. Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU In fact, it’s the perfect choice for an expansive novel by an American [email protected] Fiction Editor author at the height of her powers. LAURIE MUCHNICK [email protected] The word “blockbuster” was conceived in the 1940s as a term to Children’s Editor VICKY SMITH describe an aerial bomb capable of leveling a large building. The more [email protected] Young Adult Editor Megan Labrise we write, publish, read, and review stories that honor the diverse expe- LAURA SIMEON [email protected] riences of female, trans, and nonbinary characters, the sooner we’ll level the patriarchal Staff Writer MEGAN LABRISE playing field. [email protected] Vice President of Kirkus Indie Centering on Greer Kadetsky and Faith Frank, feminists from different generations KAREN SCHECHNER [email protected] with distinct approaches to fighting for women’s rights, contains more The Female Persuasion Senior Indie Editor DAVID RAPP than the potential to sell a lot of copies and be widely read. -

A Natural Attitude

A Natural Attitude A Naturalista’s Hair Journal Spoken from a Salon Owner’s Perspective: 4th Edition By Schatzi Hawthorne McCarthy A publication of Schatzi's Design Gallery & Day Spa, LLC A Natural Attitude: A Naturalista’s Hair Journal Spoken from a Salon Owner’s Perspective - 4th Edition By Schatzi Hawthorne McCarthy Copyright 2014-2018, Schatzi Hawthorne McCarthy; cover photo by Varick Taylor of one12images.com. Embrace the beauty of you. This book is dedicated to God, the Creator, for Your grace, mercy and omniscience: “Oh lord, though hast searched me and known me…” (Psalm 139) Thank you for guiding me, naturally and super-naturally, to this path of self-discovery that was your vision for my life. To the beautiful women in my life who have loved me unconditionally and have inspired me to be a natural woman: Grandma Mabel McMillan Aunt Joyce McCullom Woodbury Dear Mother Greta Lois McCullom Hawthorne At the footstool of this matriarchy, my natural attitude was nurtured and grown. Prayerfully, the world can learn from your rich and wise example. To my Dad, the late Retired Maj. Arthur Earl Hawthorne. You were always proud of me. Without your unconditional love, I would never have had the confidence to be the natural woman that I am. My love for you is beyond all understanding! To my beautiful family--Lloyd, Jela-ni, Jamar, who have supported me in all of my lifetime endeavors. I am privileged to walk this journey of life with you and pray that we continue to grow and learn together with hearts full of love and understanding. -

The Struggles and Resilience of Black Womanhood Through Stories of Natural Hairstyles While Attending a Predominantly White Institution

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 Getting to the Root: The Struggles and Resilience of Black Womanhood Through Stories of Natural Hairstyles While Attending a Predominantly White Institution Je'Monda Roy University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Roy, Je'Monda, "Getting to the Root: The Struggles and Resilience of Black Womanhood Through Stories of Natural Hairstyles While Attending a Predominantly White Institution" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1687. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1687 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GETTING TO THE ROOT: THE STRUGGLES AND RESILIENCE OF BLACK WOMANHOOD THROUGH STORIES OF NATURAL HAIRSTYLES WHILE ATTENDING A PREDOMINANTLY WHITE INSTITUTION A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts- Documentary Studies in the Department of Southern Studies The University of Mississippi by JE’MONDA S. ROY May 2019 Copyright Je’Monda S. Roy 2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This thesis will provide the framework for black women’s stories of struggle and resilience through natural hairstyles at a Mississippi predominantly white institution – The University of Mississippi. Although the framework of this essay is set in one institution in a state located in the Deep South, the stories and methods apply to the American society and how the lack of black representation in white spaces shape black lives, specifically black women’s lives. -

1 NOVEMBER 2020 from the Editor’S Desk: Still the Greatest Chairman by TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN

Featuring 221 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 21 | 1 NOVEMBER 2020 from the editor’s desk: Still the Greatest Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Muhammad Ali is one of those figures who seemingly exists just for writ- Chief Executive Officer ers to conjure them. Handsome, graceful, powerful, poetic, boastful—with MEG LABORDE KUEHN achievements in the ring to back it all up, not to mention a social conscience— [email protected] Editor-in-Chief he might have sprung from the pages of a novel by Ralph Ellison or Colson TOM BEER Whitehead. Who could resist the challenge of pinning this butterfly—or was [email protected] Vice President of Marketing he a bee?—to the page? SARAH KALINA That’s Ali—born Cassius Clay in 1942—on [email protected] the cover of this issue, as drawn by Dawud Anyab- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU wile to illustrate Becoming Muhammad Ali (Jimmy [email protected] Patterson/HMH Books, Oct. 5), a narrative of Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK the boxer’s childhood written by James Patter- [email protected] Tom Beer son and Kwame Alexander. In a Zoom interview Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH last month, I spoke with Patterson and Alexander [email protected] about the appeal of this larger-than-life figure. Alexander said that read- Young Readers’ Editor ing Ali’s 1975 autobiography, , “turned my reading life around LAURA SIMEON The Greatest [email protected] at age 12,” and both authors were keen to bring Ali’s voice to young read- Editor at Large ers.