Conversations with Martin Luther's Small Catechism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Synod Assembly Report

Call and Notice of Synod Assembly In accordance with Section S7.13 of the North/West Lower Michigan Synod Constitution, I hereby call and give notice of the 2017 Synod Assembly which will take place at the Comfort Inn and Suites Hotel and Conference Center, 2424 S Mission St, Mt Pleasant MI, beginning with registration at 3pm on Sunday, the 21st day of May, 2017 and concluding on Tuesday, the 23rd day of May, 2017. North/West Lower Michigan Synod Assembly – May 21-23, 2017 – Mt Pleasant MI Page 1 Table of Contents GENERAL INFORMATION Call and Notice of Synod Assembly ............................................................................... 1 Table of Contents.................................................................................................... 2-3 Conference Center Floor Plan, Area Map, etc. .............................................................. 4-6 Voting Member criteria ............................................................................................... 7 Assembly procedures ................................................................................................. 8 Procedural tips for Voting Members .............................................................................. 9 Proposed Agenda .................................................................................................10-14 Guest Speaker information ....................................................................................15-16 STAFF AND OFFICER REPORTS Greeting from Presiding Bishop Elizabeth Eaton ........................................................17-18 -

Popular Christianity, Theology, and Mission Among Tanzanian Lutheran Ministers

Shepherds, Servants, and Strangers: Popular Christianity, Theology, and Mission among Tanzanian Lutheran Ministers by Elaine Christian Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2017 © 2017 Elaine Christian All rights reserved Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from The ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. ABSTRACT Shepherds, Servants, and Strangers: Popular Christianity, Theology, and Mission among Tanzanian Lutheran Ministers Elaine Christian This dissertation is an ethnographic description of how pastors (and other ministers) in the Northern Diocese of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Tanzania understand and carry out their ministry: How they reflect, mediate, and influence local Christian practice and identities; how theology and theologizing forms an integral part of their social worlds; and how navigating and maintaining relationships with Christian mission partnerships (including “short-term mission”) becomes an important part of their ministry. Drawing from fieldwork conducted between June 2014 and September 2015, I present an account of Christianity that adds to anthropological scholarship by emphasizing the role of theology as a grounded social practice, and considers the increasingly divergent character of Christian mission and its role in modern Tanzanian Christianity. -

Can We Still See Calvary from Bethlehem?

Can We Still See Calvary from Bethlehem? By R. Guy Erwin | Volume 3.1 Fall 2016 It may come as a surprise to some that thoughts on Calvary would form the endnote to a collection of reflections on Jesus’s birth, but it shouldn’t. The two are inextricably linked. The story of God’s incarnation in human form in Jesus is at the very heart of Christian teaching, and Jesus’s birth and death are the two moments in which that Incarnation is most poignantly expressed. Both in iconography and Christian folklore, it was in medieval Europe that the conventions of depiction and description of the nativity and crucifixion of Jesus became stylized and standardized. Medieval writers and artists illustrated both the birth and death of Christ with great vividness. Every detail that could be found in the gospels was teased out and harmonized into a single expanded script by devotional writers. Gaps and missing details in the story were filled by pious imagination, each writer adding his own gloss to the versions of earlier authors. By the time of Ludolph of Saxony (ca. 1295–1378), there was a treasury of lore and information about these events; his Vita Christi (1374) filled four volumes of text in its nineteenth-century printed form, much of it focused on Jesus’s passion and death. The same phenomenon can be observed in the visual art of the period: Passion cycles were a tremendously popular and very important form of religious art from Giotto onward. Laid out like a storyboard, medieval altarpiece panels and devotional paintings telling the Passion story shaped forms of piety, such as the Stations of the Cross, that still have power and have influenced the devotion of centuries of Christians. -

Thirtieth Annual Synod Assembly

Thirtieth Annual Synod Assembly Pacifica Synod – ELCA San Diego Town and Country Resort WEDNESDAY, MAY 10 , 201 7 10:30 a.m. Executive Committee Le Sommet 1:00 p.m. Hospitality Training Pacific Ballroom 1:00 p.m. Synod Council Meeting Windsor Rose 5:30 p.m. Staff Dinner Le Sommet THURSDAY, MAY 11 , 201 7 9:00 a.m. Hospitality Training Session Pacific Ballroom 9:30 a.m. Registration Opens Golden Foyer 10:30 a.m. Hearings Budget Hearing Pacific Salon 4 Resolutions Hearing Pacific Salon 5 12:45 p.m. Gathering Music Golden Ballroom BUSINESS MEETING 1 1:00 p.m. Opening of the Assembly (Page 2 - 4) Credentials Report Nominating Committee Report, Open Floor Nominations Grant Recognition Treasurer’s Report Introductions 2:25 p.m. Keynote Address-the Rev. R. Guy Erwin, Bishop, Southwest California Synod 3:10 p.m. Synod Business Report of the Vice President Resolutions 5:00 p.m. Dinner on your own 7:00 p.m. Worship—the Rev. Andrew A. Taylor, First United Methodist Bishop of Pacifica Synod, preaching (off site: see page 2-3) 2 - 1 FRIDAY, MAY 12, 2017 BUSINESS MEETING 2 Golden Ballroom 8:30 a.m. Credentials Report Synod Council Elections 8:45 a.m. Keynote Address—the Rev. Chris Alexander 10:05 a.m. Synod business Anniversary recognition 10:20 a.m. ELCA Report-Mr. Keith Mundy 11:05 a.m. Conference Ministry Recognition 12:00 p.m. Lunch Lion Fountain Court 1:00 p.m. Vote on the Budget Golden Ballroom 1:10 p.m. Election Results 1:15 p.m. -

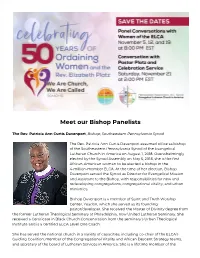

Meet Our Bishop Panelists

Meet our Bishop Panelists The Rev. Patricia Ann Curtis Davenport, Bishop; Southeastern Pennsylvania Synod The Rev. Patricia Ann Curtis Davenport assumed office as bishop of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America on August 1, 2018. Overwhelmingly elected by the Synod Assembly on May 5, 2018, she is the first African-American woman to be elected a bishop in the 4-million-member ELCA. At the time of her election, Bishop Davenport served the Synod as Director for Evangelical Mission and Assistant to the Bishop, with responsibilities for new and redeveloping congregations, congregational vitality, and urban ministries. Bishop Davenport is a member of Spirit and Truth Worship Center, Yeadon, which she served as its founding pastor/developer. She received the Master of Divinity degree from the former Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia, now United Lutheran Seminary. She received a Certificate in Black Church Concentration from the seminary’s Urban Theological Institute and is a certified ELCA Level One Coach. She has served the national church in a variety of capacities, including co-chair of the ELCA’s Guiding Coalition, member of the Congregational Vitality and African Descent Strategy teams, and secretary of the board of Lutheran Services in America. She is a lifetime member of the Philadelphia chapter of the African Descent Lutheran Association and is active with the Black Clergy of Philadelphia, Metropolitan Christian Council, Religious Leaders Council of Greater Philadelphia and Vicinity, and Christians United Against Addictions. She is the widow of Joel Davenport, with three adult children: Joel, Shanena and Jamar; and seven grandchildren, Joel III, Dominic, Chance, Cristian, Kayden, Justice and Kaleb. -

Always Proclaiming God's Saving Gospel

Always proclaiming God’s saving Gospel, living out Christ’s Great Commission, and serving all in response to God’s love —through care, advocacy, reconciliation and solidarity with those in need— the Southwest California Synod will, for the next five years, direct its work toward the following mission goals: Communicating the Gospel message powerfully and clearly Shaping the faith of the baptized through education Fostering congregations in becoming healthy communities Creating opportunities for its rostered leaders to thrive Developing at least four geographical area ministry strategies Establishing clusters of congregations around similar ministries January, 2015 GLOSSARY OF ELCA ACRONYMS AND TERMS GENERAL ELCA TERMS ELCA – Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (Denominational name). Region 2 – One of 9 regions of the ELCA composed of 5 synods (Southwest California, Pacifica, Sierra Pacific, Rocky Mountain and Grand Canyon). Churchwide – A term referring to the entire ELCA. Churchwide Offices – ELCA denominational headquarters in Chicago. Luther Center – The name for the facility in Chicago that houses the ELCA Churchwide offices. Presiding Bishop – The elected clergy responsible for the entire ELCA Churchwide; currently serving is Presiding Bishop Elizabeth Eaton. SYNOD Synod – A geographical group of congregations that are a part of the ELCA. There are 65 synods in the ELCA. SoCalSynod – Southwest California Synod (www.socalsynod.org) Conference – A geographical group of congregations of the synod: 1. Central Coast – 9 congregations located between Solvang and Templeton; 2. Channel Islands – 14 congregations between Goleta and Agoura Hills; 3. Foothill – 15 congregations in the foothills area between Glendale and Monrovia; 4. Greater Long Beach – 13 congregations in Long Beach and surrounding communities; 5. -

From Rev. R. Guy Erwin, Ph.D. President, United Lutheran Seminary

Welcome from Rev. R. Guy Erwin, Ph.D. President, United Lutheran Seminary Welcome to the United Lutheran Seminary Community I’m very glad you are here! You have taken an important step by choosing United Lutheran Seminary as a place to explore your calling to serve God. At ULS, you will be part of a nurturing and inclusive theological institution of higher learning rooted in faith in the grace and mercy of God shown in Jesus Christ. Our mission at ULS is to provide a welcoming and diverse learning community equipping people to proclaim the living Gospel for a changing church and world. ULS is a Reconciling in Christ Seminary. United Lutheran Seminary celebrates a legacy of almost 200 years of the preparation of Christian leaders dedicated to the service of God and humanity. In 2017, the two Lutheran Theological Seminaries in Gettysburg, PA (founded in 1826) and in Philadelphia, PA (founded in 1864), joined forces into one, unified United Lutheran Seminary. Our Distributed Learning community constitutes our “third campus,” and continues to grow with the need for online learning. As God calls you to this Seminary, it will be of significance to you that ULS is centered in the Lutheran confessional witness and connected to the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, and at the same time it is engaged in the truest ecumenical sense with the whole Body of Christ through its partnership with more than 25 Christian denominations. The breadth and quality of our curriculum and scope of programs are enriched by the diversity of our exemplary faculty, who are active scholars, as well as by your student colleagues and our dedicated staff. -

“The Herald” Newsletter St

“The Herald” Newsletter St. Peter’s Evangelical Lutheran Church Worship. Learn. Gather. Serve. July 2020 10 Delp Road - Lancaster, PA 17601 (717) 569-9211 “In the face of the darkness light is near.” Job 17:12 Staff The Rev. Craig A. Ross, Senior Pastor St. Peter’s Take Out Vacation Bible School [email protected] Are you ready for a delicious and fun filled week? We can’t wait! The official start The Rev. Sarah Teichmann, th th Pastor of Christian Formation date for Take Out VBS is July 20 through July 24 . You pick the time of day to [email protected] engage your child on any day that works for you. Participate from your home while Sister Dottie Almoney, social distancing. Pre-registration is required. See page 13 for more information. Parish Deaconess [email protected] The Rev. Richard E. Geib, D.D., Pastor Emeritus [email protected] The Rev. Russell Rockwell, Building Use Safety Protocol Pastor of Word of Life rrockwell@word oflifedeaf.org As our county enters into the "green" phase, we are gradually opening up the church Dr. Adam Lefever Hughes building for church activities. Be informed about what to expect. Check out the June Director of Music 24 Weekly Update for safety protocol for being in the church. Additional information [email protected] can also be found on page 2. Erik Teichmann Inside This Issue . Contemporary Worship Leader Worship Schedule - 2 [email protected] Safe Church Protocol - 2 Cindy Geesey Director of Children’s Ministries United Lutheran Seminary - 4 [email protected] Live streaming worship Adult Christian Ed. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Kirsi Stjerna

1 CURRICULUM VITAE Kirsi Stjerna First Lutheran, Los Angeles/Southwest Synod Professor of Lutheran History and Theology Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary of California Lutheran University, Berkeley, CA. Core Doctoral Faculty, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA. Docent, Theological Faculty, Helsinki University, Finland. EDUCATION Boston University Graduate School, Division of Religious and Theological Studies. Doctor of Philosophy (Religious and Theological Studies) 1995. Dissertation: “St. Birgitta of Sweden: A Study of Her Spiritual Visions and Theology of Love”. Advisor: Prof. of Church History, Carter Lindberg. University of Helsinki, Department of Theological Studies. Master of Theology (Systematic Theology and Ecumenics) 1988 (with “laudatur”). Thesis: “Pyhän Birgitan Käsitys Synnistä” [St. Birgitta's Notion of Sin] (with “laudatur”). Advisor: Prof. of Ecumenical Theology, Tuomo Mannermaa. Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas in Rome, Department of Theological Studies. Visiting scholar, studies in Ecumenical, Feminist, and Spiritual Theology. Research, Vatican Library. Fall Semester 1989. Lyseon Lukio College/High School, Mikkeli, Finland. Equivalent of Bachelor of Arts Degree (with “laudatur”) 1982. University of Helsinki, Faculty of Medical Studies. Studies in Psychiatry and Clinical Psychotherapy, 1988-1989. LANGUAGES English, Finnish (daily languages). Swedish (fluent in reading, moderate competency in writing and conversational skills). (Related languages: Norwegian and Danish – moderate reading ability.) German (fluent in reading, moderate competency in conversational skills). Latin (advanced competency in reading; doctoral level exams). Italian (competency in reading and modest conversation). Greek and Hebrew (reading and grammar; studied). Spanish, beginning. 2 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE AND EMPLOYMENT Teaching/Faculty 2016- Core Doctoral Faculty at Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA. Appointed in April 2016. Christian Theology, Spirituality, and History of Christianity. -

Martin Luther 1483 - 1546

12 Lives: Faith • Action • Witness Presentation by Bishop Guy Erwin, Southwest California Synod ELCA ● November 19, 2017 Trinity Church in the City of Boston Martin Luther 1483 - 1546 “Faith is a living, daring confidence in God's grace, so sure and certain that a man could stake his life on it a thousand times.” “The sin underneath all our sins is to Figure 1: Luther in 1526 (Lucas Cranach) trust the lie of the serpent that we cannot trust the love and grace of Christ and must take matters into our own hands.” “This is the mystery of the riches of divine grace for sinners; for by a wonderful exchange our sins are now not ours but Christ's, and Christ's righteousness is not Christ's but ours.” Figure 2: Woodcut of Luther in 1546 (School of Cranach) 12 Lives: Faith • Action • Witness Presentation by Bishop Guy Erwin, Southwest California Synod ELCA ● November 19, 2017 Trinity Church in the City of Boston Guy Erwin is Bishop of the Southwest California Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Ordained in May 2011, Erwin is the ELCA’s first synod bishop who is gay and partnered. Married to Rob Flynn, a member of the ELCA, Bishop Erwin lives in Los Angeles. Bishop Erwin is part Osage Indian and is active in the Osage Nation of Oklahoma. Erwin also served as interim pastor for two ELCA congregations in California, and as minister for worship and education at St. Matthew’s Lutheran Church in North Hollywood, California. Prior to coming to California in 2000, he was lecturer in church history and historical theology at Yale Divinity School from 1993 to 1999. -

Divinity School 2006–2007

ale university July 25, 2006 2007 – Number 5 bulletin of y Series 102 Divinity School 2006 bulletin of yale university July 25, 2006 Divinity School Periodicals postage paid New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8227 ct bulletin of yale university bulletin of yale New Haven Bulletin of Yale University The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and affirmatively seeks to Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, attract to its faculty, staff, and student body qualified persons of diverse backgrounds. In PO Box 208227, New Haven ct 06520-8227 accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against any individual on PO Box 208230, New Haven ct 06520-8230 account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, status as a special disabled Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut veteran, veteran of the Vietnam era, or other covered veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. Issued seventeen times a year: one time a year in May, November, and December; two times University policy is committed to affirmative action under law in employment of women, a year in June; three times a year in July and September; six times a year in August minority group members, individuals with disabilities, special disabled veterans, veterans of the Vietnam era, and other covered veterans. Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valerie O. -

Contributors

Contributors R. Guy Erwin (The Sacrament of the Altar) is bishop of the Southwest California Synod of the ELCA. He has served as a parish pastor, professor of Lutheran Confessional Theology at California Lutheran University, and, since 2004 as the ELCA representative to the Faith and Order Commission of the World Council of Churches. Mary Jane Haemig (The Lord’s Prayer) is professor of church history and director of the Reformation Research Program at Luther Seminary in Saint Paul, Minnesota. She specializes in the study of the Lutheran Reformation. Her interests include preaching, catechesis, and prayer in that period. She is also associate editor and book review editor of Lutheran Quarterly. Ken Sundet Jones (The Ten Commandments) is Professor of Theology and Philosophy at Grand View University in Des Moines, Iowa. As a church historian, he specializes in Martin Luther and the Reformation. He has served as a pastor in South Dakota and Iowa. Martin J. Lohrmann (Daily Prayer and the Household Chart) is assistant professor of Lutheran Confessions and Heritage at Wartburg Theological Seminary in Dubuque, Iowa. He is a pastor of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and has served congregations in Ohio and Philadelphia. Derek R. Nelson (The Apostles’ Creed) is professor of religion and holds the Stephen S. Bowen chair in the liberal arts at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana. He directs the Wabash Pastoral Leadership Program, and is a pastor of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Kirsi I. Stjerna (The Sacrament of Holy Baptism) is First Lutheran, Los Angeles/Southwest California Synod Professor of Lutheran History and Theology at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary of California Lutheran University and core doctoral faculty at Graduate Theological Union.