The Experience of Senior Student Affairs Administrators Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIOC P R E S I D E N T , KEN HATFIELD and C H E E T a H CAESAR. C

LIOC President, KEN HATFIELD and cheetah CAESAR. Caesar died recently at the age of 10 years of kidney and liver disease and is sorely missed as he was a great favorite of Ken's, often . ,. - - . h 1 vmT ic nn oaoe 13. Photo: George Collis Branch Representatives A.C.E.C. - Bob Smith, President, P.O. Box 26G, Los Angeles, CA 90026 (213) 621-4635 CANADA - Terry Foreman, Coordinator, R.R. #12, Dawson Rd., Thunder Bay, Ontario Canada P7B 5E3 CASCADE - Shelley Starns, 16635 Longmire Rd. S.E.. YeIm. WA 98597 (206) 894-2684 L.I.O.C. OF CALIFORNIA - Lora Vigne, 22 Isis St., San Francisco, CA 94102 (415) 552-3748 FLORIDA - Ken Hatfield (Acting President) 1991 S.W. 136 Ave., Davie, Florida 33325 (305) 472-7276 GREATER NEW YORK - Arthur Human, 32 Lockwood Ave., Norwalk, CT 06851 (203) 866-0484 PACIFIC NORTHWEST - Gayle Schaecher, 10715 S.E. Orient Dr., Boring, OR 97009 (503) 633-4673 SOUTHWESTERN - Rebecca Morgan, President, P.O. Box 144, Carrollton, TX 75006 (214) 241-6440 LONG ISLAND OCELOT CLUB EXOTIC CATSIGEORGIA - Cat Klass, President, 4704 NEWSLETTER Brownsville Rd., Powder Springs, GA 30073 (404) 943- 2809 Published bi-monthly by Long Island Ocelot Club. 1454 Fleetwood OREGON EDUCATIONAL EXOTIC FELINE CLUB - Drive East, Mobile. Alabama 36605. The Long Island Ocelot Club is a Barbara Wilton, 7800 S.E. Luther Rd., Portland, OR non-profit, non-commercial club. international in membership, 97206 (503) 774-1657 , devoted to the welfare of ocelots and all other exotic felines. Reproduction of the material in this Newsletter may not be made without written permission of the authors and/or the copyright owner L.I.O.C. -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

![YG Entertainment (122870 KQ) [Summary] Korea’S 2019 Media/Entertainment Competitiveness](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7182/yg-entertainment-122870-kq-summary-korea-s-2019-media-entertainment-competitiveness-1707182.webp)

YG Entertainment (122870 KQ) [Summary] Korea’S 2019 Media/Entertainment Competitiveness

2019 Outlook Media platform/Content Most favorable environment in history; focus on PR.I.C.E Analyst Jay Park +822-3774-1652 [email protected] Contents [Summary] 3 I. Outlook by segment 4 II. Medium-/long-term outlook 10 III. Key points to watch 12 IV. Global peer group (valuation) , Investment strategy 21 V. Top Picks 23 Studio Dragon (253450 KQ) YG Entertainment (122870 KQ) [Summary] Korea’s 2019 media/entertainment competitiveness Shares to be driven by content sales (p, US$m) (%) Media/content business model focused on direct sales 500 40 FTSE KOREA MEDIA indx (L) Key words: Global platforms, geopolitics, licensing fees, Domestic ad market growth (R, YoY) blockbusters, investments, leverage Broadcast content export growth (R, YoY) 400 30 Media/content business model focused on ads Key words: Domestic market, ad trends, seasonality, politics/sports 300 20 200 10 100 0 OTT export expansion in 2016-18 Chinese market lull 0 OTT export expansion in 2019F + Chinese market recovery -10 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Note: 2017 exports are based on KOCCA’s estimates; 2018 exports based on our estimates Source: Thomson Reuters, KOCCA, Cheil Worldwide, Mirae Asset Daewoo Research 3| 2019 Outlook [Media platform/Content] Mirae Asset Daewoo Research I. Outlook by segment: Media ads Ad market: Mobile and • We expect the domestic ad market to grow 3% YoY (similar to GDP growth) to W11.3tr, amid the absence of large- generalist/cable TV scale sporting events. • We forecast positive growth across all segments (except print ads), with mobile, generalist channels and cable TV channel ads are growing channels likely to drive growth. -

Colloidal Electronics

Colloidal Electronics by (Albert) Tianxiang Liu B.S. Chemical Engineering, California institute of Technology, 2014 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CHEMICAL ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN CHEMICAL ENGINEERING AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY July 2020 © 2020 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of author ............................................................................................................................. Department of Chemical Engineering July 27, 2020 Certified by ........................................................................................................................................ Michael S. Strano Carbon P. Dubbs Professor of Chemical Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by ....................................................................................................................................... Patrick S. Doyle Robert T. Haslam (1911) Professor of Chemical Engineering Graduate Officer 2 Colloidal Electronics by (Albert) Tianxiang Liu Submitted to the Department of Chemical Engineering on July 27, 2020, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chemical Engineering Abstract Arming nano-electronics with mobility extends artificial systems into traditionally inaccessible environments. Carbon nanotubes (1D), graphene (2D) and other low-dimensional materials with well-defined lattice structures can be incorporated into polymer microparticles, -

"What Is an MC If He Can't Rap?"

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 5-2019 "What Is An MC If He Can't Rap?" Dominique Jimmerson California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Jimmerson, Dominique, ""What Is An MC If He Can't Rap?"" (2019). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 569. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/569 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dominique Jimmerson Capstone Sammons 5-18 -19 “What Is an MC if He Can’t Rap?” Hip hop is a genre that has seen much attention in mainstream media in recent years. It is becoming one of the most dominant genres in the world and influencing popular culture more and more as the years go on. One of the main things that makes hip hop unique from other genres is the emphasis on the lyricist. While many other genres will have a drummer, guitarist, bassist, or keyboardist, hip hop is different because most songs are not crafted in the traditional way of a band putting music together. Because of this, the genre tends to focus on the lyrics. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

The BG News April 19, 2007

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-19-2007 The BG News April 19, 2007 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 19, 2007" (2007). BG News (Student Newspaper). 7757. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/7757 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ESTABLISHED 1920 A daily independent student press serving THE BG NEWS the campus and surrounding community Thursday April 19.2007 Volume 101. Issue 140 WWWBGNEWSCOM I ■ Vigil pays tribute to Castillon Plinko used to educate about study abroad Mother speaks out against domestic violence to honor daughter The peg and puck game was used on By K.lly Day weeks ago by her ex-boyfriend, 100 percent of homicides since campus to answer Senior Reporter Craig Daniels, Ir. 2002 in Wood County have been questions | Page 3 "This is not for what has hap- domestic violence cases. Standing on the front steps of pened, but for what will not Krueger and others who Toledo not a the Wood County Courthouse. happen in the future," Newlove attended the vigil hope to spark Kathy Newlove held a sign that said. change in the court system, city for love or read, "Alicia, My Daughter, Will Newlove is determined put which they believe isn't suf- single males Not Die in Vain.'" a stop to domestic violence. -

847-5325 [email protected]

Abbott, Cathy [RE] Retired (Ar) O: Ernie Abbott 7516 Royal Oak Dr, McLean, VA 22102-2115 H: (703) 847-5325 [email protected] C: (703) 615-8243 Abbott, Dan [RE] Retired (ER) O: 4861 Strand Dr, Virginia Beach, VA 23462-6449 H: (757) 488-4549 [email protected] C: (757) 406-1803 Acklin, Clarence [RE] Retired (W) O: Vinnie Acklin 555 Smithfield Ave, Winchester, VA 22601-5322 H: (540) 722-8928 [email protected] C: (540) 686-2716 Adams, Karen [RL] Paris Mountain (W) O: 10568 N Frederick Pike, Cross Junction, VA 22625-1507 H: (540) 888-3538 [email protected] C: (540) 539-3081 Adams, Larry [RE] Retired (RR) O: Karen S. Adams PO Box 73, Mollusk, VA 22517-0073 H: (804) 462-7737 [email protected] C: (757) 870-9683 Adkins, Cody [SY] Assistant, Saint Paul's (Craigsville) (S) O: 120 Homeplace Ln, Goshen, VA 24439-2636 H: [email protected] C: (540) 784-8829 AdkinsSr., David [RE] Retired (Rd) O: Phyllis Adkins 5000 Belmont Park Rd, Glen Allen, VA 23059-2551 H: [email protected] C: (804) 519-0815 Adkins, Greg [RE] Retired (Rn) O: Denise Adkins 3062 7 Lks W, West End, NC 27376-9315 H: [email protected] C: (703) 346-9407 Agbosu, Esther [FE] Bethany (Hampton) (YR) O: (757) 826-2493 William Agbosu 525 Dunn Cir, Hampton, VA 23666-5010 H: (757) 825-0369 [email protected] C: (804) 580-1504 Aguilar, Norma [PL] Associate, Ramsey Memorial (Rd) O: (804) 276-4628 Leopoldo Aguilar 7918 Belmont Stakes Dr, Midlothian, VA 23112-6431 H: (804) 639-6680 [email protected] C: (804) 245-6662 Ahn, Byong [RE] Retired (Ar) O: Chung Soon Ahn -

Eastern Afromontane Biodiversity Hotspot

Ecosystem Profile EASTERN AFROMONTANE BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT FINAL VERSION 24 JANUARY 2012 Prepared by: BirdLife International with the technical support of: Conservation International / Science and Knowledge Division IUCN Global Species Programme – Freshwater Unit IUCN –Eastern Africa Plant Red List Authority Saudi Wildlife Authority Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Centre for Middle Eastern Plants The Cirrus Group UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre WWF - Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Programme Office Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund And support from the International Advisory Committee Neville Ash, UNEP Division of Environmental Policy Implementation; Elisabeth Chadri, MacArthur Foundation; Fabian Haas, International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology; Matthew Hall, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Centre for Middle Eastern Plants; Sam Kanyamibwa, Albertine Rift Conservation Society; Jean-Marc Froment, African Parks Foundation; Kiunga Kareko, WWF, Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Programme Office; Karen Laurenson, Frankfurt Zoological Society; Leo Niskanen, IUCN Eastern & Southern Africa Regional Programme; Andy Plumptre, Wildlife Conservation Society; Sarah Saunders, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds; Lucy Waruingi, African Conservation Centre. Drafted by the ecosystem profiling team: Ian Gordon, Richard Grimmett, Sharif Jbour, Maaike Manten, Ian May, Gill Bunting (BirdLife International) Pierre Carret, Nina Marshall, John Watkin (CEPF) Naamal de Silva, Tesfay Woldemariam, Matt Foster (Conservation International) -

Zoey Schlemper, Even Though She Wasn’T Course in the Core Cur- the Monday After Gradu- Events

pages 6-7 Top five things to stub your toe on 5. Island counters 4. Couch Top Five Of everything 3. Door frame 2. Stairs 1. Chair leg THE CONCORDIAN ‘IVOL. 91,feel NO. 19 THURSDAY, like APRIL 16, 2015 – MOORHEAD, I MINN. am theTHECONCORDIAN.ORG token minority’ Students of color feel singled out on campus BY KALEY SIEVERT This fall, 2,381 students [email protected] enrolled and only 173 of those students are of color, Imagine going to a col- not including internation- lege where you are the mi- al students. nority. When sensitive soci- Scott Ellingson, Dean etal and cultural aspects of of Admissions, said that your race are brought up is about 7.5 percent of the in class, some people may student body. However, expect you to speak for the that percentage does not race you represent. You are include the few students afraid to speak up. who may not report their TOP PHOTO BY MADDIE MALAT This scenario is similar race when they enroll. El- Top: Kelsey Drayton, left, and Gabriel Walker stand in the Knutson Center Atrium as students walk by. to what Concordia juniors lingson said Admissions Above: Gabriel Walker is featured on Concordia’s website, a picture he thought would be of the entire table he was sit- Gabriel Walker and Kelsey gives students a choice to ting at in dining services. Drayton have felt while at- provide their race, but do ment to show how diverse was featured, Walker was think they used it for diver- and 5.7% of the two years tending Concordia College, not require them to. -

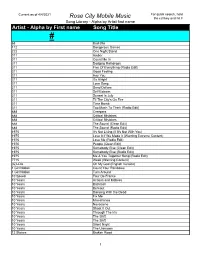

Alpha by First Name Song Title

Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title # 68 Bad Bite 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Amber 311 Count Me In 311 Dodging Raindrops 311 Five Of Everything (Radio Edit) 311 Good Feeling 311 Hey You 311 It's Alright 311 Love Song 311 Sand Dollars 311 Self Esteem 311 Sunset In July 311 Til The City's On Fire 311 Time Bomb 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 888 Creepers 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 The Sound (Clean Edit) 888 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 It's Not Living (If It's Not With You) 1975 Love It If We Made It (Warning Extreme Content) 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 1975 People (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) 1975 Me & You Together Song (Radio Edit) 7715 Week (Warning Content) (G)I-Dle Oh My God (English Version) 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Burnout 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Novacaine 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years The Shift 10 Years The Shift 10 Years Silent Night 10 Years The Unknown 12 Stones Broken Road 1 Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975. -

Open MB Final Revised Dissertation.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications TRAP(PED) MUSIC AND MASCULINITY: THE CULTURAL PRODUCTION OF SOUTHERN HIP-HOP AT THE INTERSECTION OF CORPORATE CONTROL AND SELF-CONSTRUCTION A Dissertation in Mass Communications by Murali Balaji ○c 2009 Murali Balaji Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 The dissertation of Murali Balaji was reviewed and approved* by the following: Matthew P. McAllister Professor of Communications Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee C. Michael Elavsky Assistant Professor of Communications Matthew Jordan Assistant Professor of Communications Keith B. Wilson Professor of Education Ronald L. Jackson Special Member Professor of Communications Dean, College of Media, University of Illinois John S. Nichols Associate Dean, Graduate School College of Communications *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Black masculinity has been represented and reproduced in hip-hop since its beginnings in the 1970s. However, the production of Black masculinity in rap has relied increasingly on problematic cultural tropes, particularly variations of images such as the thug and the playa. Geographic space is also used in this cultural construction. The cultural industries have long conflated ―authentic‖ Blackness with the Northern urban ghetto, particularly in cities such as New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. However, the expansion of the cultural industries in the U.S. South and images of Southern Black masculinity