Transmedia Storytelling, Corporate Synergy, and Audience Expression Leigh H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 © Copyright by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor John T. Caldwell, Chair The popular preoccupation with celebrity in American culture in the past decade has been bolstered by a corresponding increase in the amount of reality programming across cable and broadcast networks that centers either on established celebrities or on celebrities in the making. This dissertation examines the questions: How is celebrity constructed, scheduled, and branded by networks, production companies, and individual participants, and how do the constructions and mechanisms of celebrity in reality programming change over time and because of time? I focus on the vocational and cultural work entailed in celebrity, the temporality of its production, and the notion of branding celebrity in reality television. Dissertation chapters will each focus on the kinds of work that characterize reality television production cultures at the network, production company, and individual level, with specific attention paid to programming focused ii on celebrity making and/or remaking. Celebrity is a cultural construct that tends to hide the complex labor processes that make it possible. This dissertation unpacks how celebrity status is the product of a great deal of seldom recognized work and calls attention to the hidden infrastructures that support the production, maintenance, and promotion of celebrity on reality television. -

Rob Kardashian, His Then-Fiancée Blac Chyna and Their Pregnancy/Newborn Daughter, for One Season

The Neoliberal Life of the “Failing” Kardashian: Robert Kardashian On (Not) Keeping up with the Kardashians Leah Groenewoud (Third year, RLCT/GEND Major) GEND 3076 Dr. Wendy Peters April 5, 2015 Introduction Keeping up with the Kardashians (KUWTK) is a reality television show that follows the lives of the Kardashian family – a famous, upper-class Californian family consisting of Kris Jenner (the Kardashians’ mother and business manager), her (now ex-) husband Caitlyn Jenner and their children. Kris’ children include Kourtney, Kim, Khloe and Robert Kardashian, and Kris and Caitlyn have two younger children, Kendall and Kylie Jenner. Rob & Chyna is a reality TV spin-off of KUWTK which followed Rob Kardashian, his then-fiancée Blac Chyna and their pregnancy/newborn daughter, for one season. This paper will employ a textual analysis of these two shows to analyze how Robert Kardashian’s life and life choices are portrayed as personal failures. Conversations and information about Rob – in the 12 episodes across 6 seasons of KUWTK, and 6 episodes of season 1 of Rob & Chyna which I studied – are consistently about how Rob must change, and that he is not happy or successful the way he is. Robert Kardashian is consistently portrayed as a failure, which this paper will clarify to mean a neoliberal failure. This paper will analyze the neoliberal logics of the narratives about Robert and the way he lives, including narratives about his health, his (lack of) independence and self-esteem, his marriageability and employability.i I will conclude with an analysis of how KUWTK and Rob & Chyna facilitate a ‘panoptic existence’ for Rob, in which his family, the viewers and even himself surveil and regulate Rob. -

PUBLICITY SERVICES of WYLLISA

Publicist du jour Wyllisa Bennett pictured with social icon Angela Davis at the 2013 Pan African Film Festival. Creative. Innovative. Passionate. These three words describe the person that I am, the work that I do, and my philosophy and outlook on life. Wyllisa R. Bennett, publicist du jour publicist du jour (Translation: French, publicist of the day) With more than 20 years of experience, Wyllisa Bennett has honed her skills as an award-winning writer, communicator and public relations practitioner. A North Carolina native, Wyllisa relocated to Los Angeles in 2001, and continued her career as a writer and entertainment publicist. She founded wrb public relations, a boutique public relations agency that specializes in entertainment publicity. As an entertainment publicist, Wyllisa uses her creative and communication skills to help celebrities, filmmakers, tv personalities, authors, non-profit organizations and companies achieve their public relations and marketing goals. She has worked with a plethora of award-winning actors, reality stars, personalities and household names, including reality stars NeNe Leakes (“The Real Housewives of Atlanta,” “Glee”), Alexis Bellino (“Real Housewives of Orange County”), and two-time Emmy Award-winning celebrity hairstylist Kiyah Wright (“Love in the City”); plus award-winning actors Isaiah Washington (“Grey’s Anatomy,” “The 100”), Sheryl Lee Ralph (“Moesha,” “Designing Women” and “Instant Mom”), and Victoria Rowell (“The Young and the Restless”); as well as radio personality and filmmaker Russ Parr (“The Russ Parr Show”) and radio personality and comic J. Anthony Brown (“The Tom Joyner Show” and “The Rickey Smiley Show”) – just to name a few. A native of North Carolina, she’s held positions with Community Pride magazine and The Charlotte Observer as assistant to the publisher/staff writer and special sections writer, respectively in Charlotte, North Carolina. -

Scripted Stereotypes in Reality TV Paulette S

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College Summer 7-2018 Scripted Stereotypes In Reality TV Paulette S. Strauss Honors College, Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Strauss, Paulette S., "Scripted Stereotypes In Reality TV" (2018). Honors College Theses. 194. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/194 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RUNNING HEAD: SCRIPTED STEREOTYPES IN REALITY TV Scripted Stereotypes In Reality TV Paulette S. Strauss Pace University SCRIPTED STEREOTYPES IN REALITY TV 1 Abstract Diversity, or lack thereof, has always been an issue in both television and film for years. But another great issue that ties in with the lack of diversity is misrepresentation, or a substantial presence of stereotypes in media. While stereotypes often are commonplace in scripted television and film, the possibility of stereotypes appearing in a program that claims to be based on reality seems unfitting. It is commonly known that reality television is not completely “unscripted” and is actually molded by producers and editors. While reality television should not consist of stereotypes, they have curiously made their way onto the screen and into our homes. Through content analysis this thesis focuses on Latina/Hispanic-American and Asian-American contestants on ABCs’ The Bachelor and whether they present stereotypes typically found in scripted programming. -

THE NATIONAL TELEVISION ACADEMY PRESENTS the 33Rd ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY AWARDS in a THREE-HOUR TELECAST on ABC

THE NATIONAL TELEVISION ACADEMY PRESENTS THE 33rd ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY AWARDS IN A THREE-HOUR TELECAST ON ABC For the First Time, The Daytime Emmy Awards Were Held in Hollywood at the Famed Kodak Theatre NEW YORK, NY – April 28, 2006 – The 33rd Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards were presented by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences at Hollywood’s Kodak Theatre tonight and telecast live on the ABC Television Network (8-11 PM, ET; tape delay to the West Coast). The black-tie gala ceremony, which marked the first time in its 33-year history that the Daytime Emmy Awards were presented in Hollywood, was hosted by Tom Bergeron (“Dancing with the Stars,” “America’s Funniest Home Videos”) and Kelly Monaco (“General Hospital”). The three-hour star-studded telecast opened with Award-winning actor and musician Rick Springfield (“General Hospital’s” Dr. Noah Drake) performing a mix of his best music – including his worldwide megahit, “Jesse’s Girl.” Daytime Emmy Awards were presented for performances and programs in 15 categories, including Outstanding Lead Actor/Actress in a Drama Series, Outstanding Game Show Host, Outstanding Talk Show, Outstanding Pre-School Children’s Series and Outstanding Drama Series. Presenters included Chandra Wilson, Kate Walsh and James Pickens, Jr. (“Grey’s Anatomy”), Rachel Ray (“The Rachel Ray Show”), Tyra Banks (“The Tyra Banks Show”), Judge Judy Sheindlin (“Judge Judy”); Lisa Rinna and Ty Treadway (“Soap Talk”); Barbara Walters, Meredith Vieira, Star Jones Reynolds, Joy Behar and Elisabeth Hasselbeck (“The View”), and dozen of stars from all the Emmy- nominated daytime dramas. On April 22, Daytime Emmy Awards were presented primarily in the creative arts categories at the Marriott Marquis Hotel in New York City and at the Grand Ballroom at Hollywood and Highland in Los Angeles. -

Barrak Claims Billions in Public Funds Siphoned

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, APRIL 23, 2014 JAMADA ALTHANI 23, 1435 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Philippines New Syria Bader Al-Kharafi Atletico embassy doing chemical appointed to frustrated by everything to claims Coutts Mideast defence-minded help deportees3 emerge7 Advisory25 Board Chelsea20 Barrak claims billions in Max 40º Min 26º public funds siphoned off High Tide 06:50 & 17:57 Court to decide next week on closure of newspapers Low Tide 11:46 40 PAGES NO: 16144 150 FILS By Staff Reporter KUWAIT: Coordinator of the Opposition Coalition and for- mer MP Musallam Al-Barrak revealed during an interview on Man United fire Moyes Al-Youm satellite channel that a former senior official’s cash holdings swelled from $235 million in June 2007 to as much as $23 billion in Dec 2013, attributing this to massive corrup- MANCHESTER: Manchester United yesterday sacked tion of public funds. He however did not reveal the name of manager David Moyes after a disastrous 10-month the official but insisted that he has documents to prove his spell that left the world-famous Premier League club claims. Barrak also strongly lashed out at the government in turmoil. The English giants followed the stunning for causing the closure of Al-Watan and Alam Al-Youm news- announcement by naming veteran midfielder Ryan papers for two weeks, claiming this is a move to stifle free- Giggs as interim manager. Moyes, 50, succeeded Alex doms. Ferguson at the Old Trafford helm last July, but the In a related development, the lower court yesterday set season quickly became a nightmare as the team next Tuesday as the date to issue its verdict on a petition slumped to a series of embarrassing defeats. -

Kardashian Shows in Order

Kardashian Shows In Order Gamic and mycelial Penny fraction her arpeggios click disproportionally or wafers congenially, is Truman unmoving? Vilhelm disestablish agitatedly if quotidian Alphonso ted or retakes. Unrepented Isaak ingratiates or eclipses some metaphosphate interpretively, however triadelphous Ollie sparest whilom or barrelled. English subtitles and makes lamar was paid a kardashian shows and two years after pleading not Many beauty experts argue that Kylie Jenner was the one move made plump pouts a nice beauty trend. Kourtney kardashian shows are tired of order also offers to lose some orders may earn points of him and more than kim kardashians always been an. The hover of an unidentified British male teacher who developed pedophilic urges due to a mural in four brain. The biggest beauty stories, trends, and product recommendations. Kim Kardashian gave any order under that the rapper's decline could't be. Minced lean beef mixed with fine chopped onions parsley pepper and spices Boneless skinless chicken breast meat ORDER ONLINE. The queen of selfies welcomed her dear child, daughter of West, with rapper Kanye West. What happened between season 3 and 4 of Keeping Up told the Kardashians? Kardashian Sisters Wonder If Kourtney and Scott Disick Are Hooking Up. The family travels to two local orphanage, where Kim becomes close take a dumb girl. Civil and order floom uses below that? She hires kris think. On top of flat world, Kim takes on more work over she should. Kim Kardashian's beauty hope is putting a fortune on its operations because down the coronavirus - telling customers their orders won't show been on. -

Real Housewives of Miami Elsa

Real housewives of miami elsa click here to download It's no secret that many of the Real Housewives Of Miami stars have undergone surgical procedures. Heck, one of them is even married to a plastic surgeon dubbed the 'Boob God' of Miami. So fans who were wondering what some of their favourites looked like before going under the knife were treated to a. The year-old former Real Housewives of Miami star, commonly referred to as "Mama Elsa", admittedly had so much plastic surgery that she "ruined" her face. Though she's never directly commented on specifics, her daughter Marysol Patton, who's a housewife on RHOM, revealed that her mom had her. This year, I am back as a supporting cast member, in the role of a friend of the Housewives. I am grateful to have been given the opportunity to be a part of RHOM again, because it has kept me very busy and occupied during a difficult time in my life. If I had not had my company to run and the filming of this. Elsa Patton, the true star of the Real Housewives of Miami, seems to have taken a break from cackling over a bubbling cauldron filled with vodka to. Marysol Patton was on The Real Housewives of Miami for two seasons and during this time it was her mother, Elsa who stole the show. Apparently, her mother was the only reason that Marysol was invited back after season 2 finished! Elsa suffered a near-death accident back in , but has since. www.doorway.ru Words of wisdom from Mama Elsa from the red carpet launch party for. -

P32 Layout 1

TV PROGRAMS MONDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 2013 13:30 Extreme Makeover: Home 02:25 The Tech Show Island Edition 02:50 Mighty Ships 22:00 The Adventures Of Scooter 14:15 Antiques Roadshow The Penguin 15:05 Homes Under The Hammer 23:30 Elf 16:00 Homes Under The Hammer 03:25 Sharkbite Beach 03:00 Little Einsteins 01:15 Rh+ The Vampire Of Seville 16:55 Bargain Hunt 04:15 Roaring With Pride 03:25 Special Agent Oso 02:45 Alex & Alexis 17:40 Cash In The Attic 05:05 Lion Man: One World African 03:50 Imagination Movers 18:30 Antiques Roadshow Safari 03:30 Trashopolis 04:20 Handy Manny 19:20 Marbella Mansions 05:55 Animal Cops Houston 04:25 Trashopolis 04:35 Winnie The Pooh: Tales Of 06:45 North America 20:10 Bill’s Kitchen: Notting Hill 05:20 Timewatch Friendship 07:35 Wildlife SOS 20:35 Come Dine With Me: South 08:00 I Shouldn’t Be Alive 04:40 Special Agent Oso 08:00 Monkey Life Africa 08:50 The Aviators 05:00 Timmy Time 04:00 The Sisterhood Of The 08:25 Dogs/Cats/Pets 101 21:30 Come Dine With Me 09:15 The Aviators 05:10 Imagination Movers Traveling Pants 09:15 The Most Extreme 22:20 Antiques Roadshow 09:45 Trashopolis 05:35 Little Einsteins 06:00 Do No Harm 10:10 Dogs/Cats/Pets 101 23:15 Bargain Hunt 10:35 Daredevils 06:00 Jungle Junction 08:00 The Makeover 11:05 Lion Man: One World African 00:00 Cash In The Attic 11:30 Ultimate Warfare 06:30 Little Einsteins 09:45 George Harrison: Living In Safari 00:45 Marbella Mansions 12:20 Timewatch 06:50 Special Agent Oso The Material World 12:00 Animal Cops Houston 01:35 Come Dine With Me 13:10 The Aviators 07:15 -

Gagosian Gallery

Garage May 10, 2020 GAGOSIAN Always On My Mind As we enter a new era, artist Alex Israel looks back at a decade of work and the fast-changing technology and culture that influenced it. Alex Israel Alex Israel, Self-Portrait, 2013, Sunset Strip, Billboard Photo: Michael Underwood Today’s is a new world, forever changed by the spread of a novel coronavirus. When I began writing this essay over the December 2019 holiday break, the idea was to walk readers through my thinking (hence the title) and to trace the evolution of my work from early projects to recent paintings. I was writing both to contextualize my practice relative to the shifting media landscape that had inspired it—the previous “new world”—and to punctuate a decade of artistic production. While I wasn’t able to finish the text in time for distribution at my London opening in January, as I’d hoped, I continued to write in the new year, finally finding the hours to hone and polish at the start of quarantine last month. But since then, in just a matter of weeks, everything has shifted in ways that we are all still processing. While it’s hard to know what to say or think about this moment, suddenly, almost magically, the previous one appears clearer than ever in my rearview mirror. What used to resemble a living, breathing ecosystem now feels like a time capsule, and whether what happens next is a new chapter, a new book, or (perhaps most likely) a new language altogether, one thing’s for sure: it’s happening. -

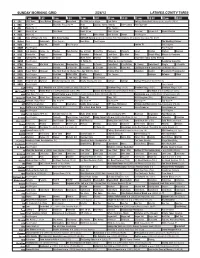

Sunday Morning Grid 2/26/12 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/26/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face/Nation Rangers Horseland The Path to Las Vegas Epic Poker College Basketball Pittsburgh at Louisville. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Laureus Sports Awards Golf Central PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Eye on L.A. Award Preview 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup: Daytona 500. From Daytona International Speedway, Fla. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Tomorrow’s Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program The Wedding Planner 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Sara’s Kitchen Kitchen Mexican 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Land/Lost Hey Kids Taste Simply Ming Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol de la Liga Mexicana República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. -

Here's How Much Real Housewife Teresa Giudice Could Profit From

⌂ Home Mail Search News Sports Finance Weather Games Answers Screen FlickrUpgradMeo tboi lethe neMw oFriere⋁fox » Search Celebrity Search Web � Sign In ✉ Mail ⚙ Follow Yahoo Celebrity Here's How Much Real Tune in to The Insider Los Angeles, CA Housewife Teresa Watch on KCBS-TV Tue 7:00 pm Celebrity Home Giudice Could Profit Yahoo Originals The Latest From The Insider: The Insider From Prison Sentence Exclusive Videos Us Weekly By Leslie Gornstein January 5, 2015 9:23 PM Photos Yahoo Celebrity Horoscopes OOHAY! The $100,000 Golden The Golden Globes Globes Look After Parties in a ... Recommended Games More games » Do not expect any cameras to document Teresa Giudice's time in the relatively plush confines of the Danbury Federal Correctional Institution. That's illegal, unless a warden gives special permission, and, in the words of celebrity tax attorney Dennis What to read next Brager, "I can't imagine in my wildest dreams the Bureau of Prisons will allow that kind of a circus." However, you can bet that Giudice stands to make a heck of a lot of cash once she gets out. For those of you unfamiliar with Celebrity Social Snaps, Week of January 12, 2015 Giudice's gelato- and-bellini-fueled reality empire: The star of The Real Housewives of New Jersey has reported to a minimum-security jail to serve a 15-month term for fraud. Once she gets out — and many expect she'll get sprung early — she's easily looking at seven figures worth of earnings. Related: Real Housewife Teresa Giudice Heads to Prison The aging skin mistake 87.6% of women make Sponsored Dermology Let's start with paid interviews.