Detroit Housing Code Enforcement and Community Renewal: a Study in Futility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

333 North Michigan Buildi·N·G- 333 N

PRELIMINARY STAFF SUfv1MARY OF INFORMATION 333 North Michigan Buildi·n·g- 333 N. Michigan Avenue Submitted to the Conwnission on Chicago Landmarks in June 1986. Rec:ornmended to the City Council on April I, 1987. CITY OF CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Planning and Development J.F. Boyle, Jr., Commissioner 333 NORTH MICIDGAN BUILDING 333 N. Michigan Ave. (1928; Holabird & Roche/Holabird & Root) The 333 NORTH MICHIGAN BUILDING is one of the city's most outstanding Art Deco-style skyscrapers. It is one of four buildings surrounding the Michigan A venue Bridge that defines one of the city' s-and nation' s-finest urban spaces. The building's base is sheathed in polished granite, in shades of black and purple. Its upper stories, which are set back in dramatic fashion to correspond to the city's 1923 zoning ordinance, are clad in buff-colored limestone and dark terra cotta. The building's prominence is heightened by its unique site. Due to the jog of Michigan Avenue at the bridge, the building is visible the length of North Michigan Avenue, appearing to be located in the center of the street. ABOVE: The 333 North Michigan Building was one of the first skyscrapers to take advantage of the city's 1923 zoning ordinance, which encouraged the construction of buildings with setback towers. This photograph was taken from the cupola of the London Guarantee Building. COVER: A 1933 illustration, looking south on Michigan Avenue. At left: the 333 North Michigan Building; at right the Wrigley Building. 333 NORTH MICHIGAN BUILDING 333 North Michigan Avenue Architect: Holabird and Roche/Holabird and Root Date of Construction: 1928 0e- ~ 1QQ 2 00 Cft T Dramatically sited where Michigan Avenue crosses the Chicago River are four build ings that collectively illustrate the profound stylistic changes that occurred in American architecture during the decade of the 1920s. -

M I C H I G a N Real Property Review

MICHIGAN REAL PROPERTY REVIEW Published by the Real Property Law Section State Bar of Michigan Spring 2007 Vol. 34, No. 1 CONTENTS Chairperson’s Report ......................................................................................................5 by Patrick A. Karbowski Counting on Redivision Rights? ...................................................................................... 7 by David W. Charron Enhancing the Deal: Integrating Government Incentives Into Real Estate Transactions ........................................................................................18 by Grant W. Williams Forfeiture Road Map .................................................................................................... 31 by Jonathan T. Walton, Jr. and Laura S. Donnelly Deed Restrictions In Michigan ......................................................................................37 by William E. Hosler Legislation Affecting Real Property ...............................................................................50 by C. Leslie Banas Judicial Decisions Affecting Real Property ....................................................................54 by C. Leslie Banas Continuing Legal Education .........................................................................................60 by David E. Nykanen and Arlene R. Rubinstein MICHIGAN REAL PROPERTY REVIEW Published by the Real Property Law Section State Bar of Michigan Spring 2007 Vol. 34, No. 1 The Michigan Real Property Review is the official journal of the Real Property -

0101 Office of the Governor 0301 Legislative Auditor

SOM Workforce Report - as of March 30, 2016 0101 OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR Count Location Cd Desc County Cd Des Addr1 City State Zip Cd 1 CADILLAC PLACE WAYNE 3040 W GRAND BLVD DETROIT MI 48202 1 GRAND RAPIDS STATE OFC BLDG KENT 350 OTTAWA AVE NW GRAND RAPIDS MI 49503 1 MARQUETTE CO OFFICE MARQUETTE 234 W BARAGA AVE MARQUETTE MI 49855 51 ROMNEY BUILDING INGHAM 111 S CAPITOL AVE LANSING MI 48933 Total For 0101 OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR: 54 0301 LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR GENERAL Count Location Cd Desc County Addr1 City State Zip Cd 154 VICTOR BUILDING INGHAM 201 N WASHINGTON SQ LANSING MI 48933 Total For 0301 LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR GENERAL: 154 0701 TECH, MGMT AND BUDGET - MB Count Location Cd Desc County Addr1 City State Zip Cd 9 ARBAUGH BLDG INGHAM 401 WASHINGTON SQ S LANSING MI 48933 44 CADILLAC PLACE WAYNE 3040 W GRAND BLVD DETROIT MI 48202 21 CAPITOL COMMONS CENTER INGHAM 400 S PINE ST LANSING MI 48933 76 CONSTITUTION HALL INGHAM 525 W ALLEGAN ST LANSING MI 48915 8 CONSTRUCTION & TECHNOLOGY BLDG EATON 8885 RICKS RD LANSING MI 48917 1 DICKINSON CO OFFICE DICKINSON 1238 CARPENTER AVE IRON MOUNTAIN MI 49801 1 ESCANABA STATE OFFICE BLDG DELTA 305 LUDINGTON ST ESCANABA MI 49829 6 FLINT STATE OFFICE BUILDING GENESEE 125 E UNION ST FLINT MI 48502 1 GAYLORD OPRS SERVICE CENTER OTSEGO 1732 W M 32 GAYLORD MI 49735 91 GENERAL OFC BUILDING DIMONDALE EATON 7150 HARRIS DR LANSING MI 48913 101 GENERAL SERVICES EATON 7461 CROWNER DR LANSING MI 48917 5 GRAND RAPIDS STATE OFC BLDG KENT 350 OTTAWA AVE NW GRAND RAPIDS MI 49503 13 GRAND TOWER BLDG INGHAM 235 S GRAND AVE -

LID - Left NONE CDB.Qxp 10/13/2014 4:16 PM Page 1 CDB Living in the D New CD Magazine Sized 10/6/2014 3:18 PM Page 1

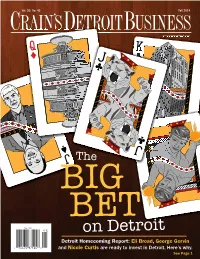

LID - Left _NONE CDB.qxp 10/13/2014 4:16 PM Page 1 CDB Living In The D_New CD Magazine sized 10/6/2014 3:18 PM Page 1 Let’s do this together... We couldn’t be more excited about The District Detroit, a project that engages the entire city, has a far reaching impact for our community, its people, workers and businesses from every corner of the state. We can, and we are, changing the conversation about Detroit. It’s an incredible comeback story in the making. Learn more at DistrictDetroit.com 20141020-SUPP--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 10/15/2014 5:12 PM Page 1 FALL 2014 Page 1 FALL 2006 doing business in our bilities and future of Detroit.” Publisher’s note state. The research is clear: Billionaire/philanthropist Eli Broad spoke Metro areas with strong on the opening night about opportunities in ake no mistake, there is a big bet on core cities do better eco- Detroit and how improving education was key. Detroit. nomically than those that Nicole Curtis, host of “Rehab Addict” on ca- M In this special annual Detroit-fo- don’t. Everybody has a ble TV, announced she would focus the sixth cused supplement, we outline just a few: stake in Detroit’s financial season of her popular show on homes in De- ■ Gov. Rick Snyder bet his political capi- well-being. troit. tal that bankruptcy was Detroit’s best path But to become truly sus- Or this from a top executive in the head- to a sustainable future. tainable, Detroit needs investments to create hunting world: “It felt good to be back in ■ Mayor Mike Duggan, a Democrat, jobs for lower-income — and lower-skilled — Detroit and welcomed by the city that raised took a calculated risk that working with Detroiters, and better schools to attract and me,” wrote Billy Dexter, a Chadsey High Snyder’s Republican team and Emergency keep residents. -

Historical Collections. Collections and Researches Made by the Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society

Library of Congress Historical Collections. Collections and researches made by the Michigan pioneer and historical society ... Reprinted by authority of the Board of state auditors. Volume 10 Henry Fralick. PIONEER COLLECTIONS COLLECTIONS AND RESEARCHES MADE BY THE PIONEER SOCIETY OF THE STATE OF MICHIGAN Michigan pioneer and state historical society. SECOND EDITION VOL. X. LC LANSING WYNKOOP HALLENBECK CRAWFORD COMPANY, STATE PRINTERS 1908 PREFACE TO SECOND EDITION—VOLUME X In comparing this volume with the first edition, not many changes will be found, as the object of the revision was to correct obvious errors and to make brief explanatory comments rather that to substitute the editor's opinions and style for those of the contributors to the archives of the Society. But even this has called for a great amount of research to verify dates and statements of fact. Only errors obviously due to the carelessness of copyists or printers have been corrected without explanation: where there Historical Collections. Collections and researches made by the Michigan pioneer and historical society ... Reprinted by authority of the Board of state auditors. Volume 10 http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.5298c Library of Congress is a probable mistake, a brief comment, or another spelling of the name or word, has been inserted in brackets. The usual plan of using foot notes, was not available, because, by so doing. the paging of the first edition would not have been preserved and the index to the. first fifteen volumes would have been of use only for the first edition: therefore the notes have been gathered into an appendix, each numbered with the page to which it refers. -

The Building Tradesman the Building Tradesman

THETHE BUILDINGBUILDING TRADESMANTRADESMAN Official Publication of the Michigan Building and Construction Trades Council VOL. 70, NO. 3 Since 1952 • Serving the highly skilled men and women in Michigan’s building trade unions 65 Cents February 12, 2021 SHORT Unions, more or less, CUTS held their own during COVID-impacted year Unions elections By Marty Mulcahy going electronic? Editor Labor’s numbers are With the pandemic raging, The annual federal govern- down, but workforce the National Labor Relations ment report on the statistical state Board (NLRB) has had to face of the nation’s labor unions has percentage is up; the reality that in-person voting almost never offered an opportu- not bad, Michigan in a union election might not be nity for a “good news” headline safe. To fix this Congressman for organized labor in any year in Shierholz. “Due to this, unionized Andy Levin (D- MI, 9th District), recent decades. workers have had a voice in how introduced a bill to allow elec- And, 2020 was no different, their employers have navigated tronic voting. but there were some glad tidings the pandemic, including negoti- The bill, known as the for a very difficult year. ating for terms of furloughs or SAFE Worker Act, was intro- The Bureau of Labor Statis- work-share arrangements to save duced into the new Congress in tics reported on Jan. 22 that the jobs. This likely played a role in January. The bill would repeal a nation’s labor unions represented limiting overall job loss among ban on electronic voting and 15.9 million workers, a decline of unionized workers.” would order the NLRB to de- ANCHORAGE POINTS for the foundation that will support the tower on the Detroit side of the 444,000 from 2019. -

Allied Proposal -2014 ISID Design Build Tenat Fit-Out Services 481332 7.Pdf

ORIGINAL Submitted by: Allied Building Service 1801 Howard St Detroit, Michigan 48216 313-230-0800 State of Michigan: Request for Proposal 2014 Indefinite-Scope, Indefinite-Delivery Design-Build Services for Tenant Fit-Out Work Various Locations, Michigan Due Date: January 16, 2014 Time Due: 2:00pm Local Time Submitted to: Michigan Department of Technology, Management and Budget Facilities and Business Services Administration Design and Construction Division 7150 Harris Road Third Floor ‘B’ Wing, General Office Building Dimondale, MI 48821 Table of Contents PART 1 - TECHNICAL PROPOSAL: ............................................................................................................. ….2 I - 1 Understanding of Project Tasks ..............................................................................................................2 I - 2 Personnel.................................................................................................................................................4 I - 3 Management Summary and Work Plan/Schedule ..................................................................................7 I - 4 Questionnaire ..........................................................................................................................................9 PART 2 - COST PROPOSAL:………………………………………………………………………………………… 11 II-1A - Position, Classification & Employee Billable Rate Information………………………………………….11 Appendices Appendix A – Questionnaire Appendix B – Key Personnel Resumes Appendix C – Project Examples -

7344 Filed 09/08/14 Entered 09/08/14 20:47:51 Page 1 of 392

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION ----------------------------------------------------x : : In re: Chapter 9 : CITY OF DETROIT, MICHIGAN, : Case No. 13-53846 : Debtor. Hon. Steven W. Rhodes : : ----------------------------------------------------x SECOND AMENDED STIPULATION TO ENTRY OF SECOND AMENDED JOINT FINAL PRETRIAL ORDER BY DEBTOR AND CERTAIN PLAN OBJECTORS Pursuant to Local Bankruptcy Rule 7016-1 and paragraph 6(c) of the Eighth Amended Order Establishing Procedures, Deadlines and Hearing Dates Relating to the Debtor’s Plan of Adjustment (Aug. 13, 2014) [Dkt. 6699], (a) the City of Detroit, Michigan (the “City”), the proponent of the Sixth Amended Plan for the Adjustment of Debts of the City of Detroit (Aug. 20, 2014) [Dkt. 6908] (as it may be further amended, modified or supplemented, and including all exhibits and attachments thereto, the “Plan”), (b) certain supporters of the Plan (collectively with the City, the “Plan Supporters”), including The Detroit Institute of Arts, a Michigan nonprofit corporation (the “DIA Corp.”), the Official Committee of 13-53846-swr Doc 7344 Filed 09/08/14 Entered 09/08/14 20:47:51 Page 1 of 392 Retirees of the City of Detroit (the “Committee”), the Police and Fire Retirement System of the City of Detroit and the General Retirement System of the City of Detroit (together, the “Retirement Systems”), the Detroit Police Officers Association (the “DPOA”), the Retiree Association Parties, and the State of Michigan, and (c) certain objectors to the Plan (collectively, the “Objectors”), including (i) Syncora Guarantee Inc. and Syncora Capital Assurance Inc. (together, “Syncora”), (ii) Financial Guaranty Insurance Company (“FGIC”), (iii) Assured Guaranty Municipal Corporation (“Assured”), (iv) National Public Finance Guarantee Corporation (“National”), (v) Berkshire Hathaway Assurance Corporation (“BHAC”), (vi) U.S. -

Year Book, 19521953

University of Mississippi eGrove American Institute of Certified Public Association Sections, Divisions, Boards, Teams Accountants (AICPA) Historical Collection 1952 Year Book, 1952-1953 American Woman's Society of Certified Public Accountants American Society of Women Accountants Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_assoc Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation American Woman's Society of Certified Public Accountants and American Society of omenW Accountants, "Year Book, 1952-1953" (1952). Association Sections, Divisions, Boards, Teams. 541. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_assoc/541 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Historical Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Association Sections, Divisions, Boards, Teams by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. American Woman's Society of Certified Public Accountants American Society of Women Accountants Year Book 1952-1953 American Womans' Society of Certified Public Accountants American Society of Women Accountants Year Book 1952-1953 TABLE OF CONTENTS AMERICAN WOMAN'S SOCIETY OF CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS 1952/1953 Officers and Directors Page 3 Past Officers and Directors 4 Purpose and Objective 7 Constitution and By-laws 9 Membership - Alphabetical 14 Membership - Geographical 33 AMERICAN SOCIETY OF WOMEN ACCOUNTANTS 1952/1953 National Officers and Directors Page 43 National Past Officers 44 National Past Directors 45 History 47 By-laws 48 Chapters: Atlanta Charter No. 12 56 Buffalo Charter No. 23 63 Chicago Charter No. 2 67 Cincinnati Charter No. 25 73 Cleveland Charter No. -

Construction Manager at Risk Detroit

Detroit Wayne County Port Authority NEW PUBLIC DOCK & TERMINAL BUILDING SEP-14 FINAL REPORT Innovative Contracting Practices SPECIAL EXPERIMENTAL PROJECT - 14 CONSTRUCTION MANAGER AT RISK for NEW PUBLIC DOCK & TERMINAL BUILDING DETROIT, MICHIGAN ArchivedFINAL REPORT December 1, 2012 Page 1 Detroit Wayne County Port Authority NEW PUBLIC DOCK & TERMINAL BUILDING SEP-14 FINAL REPORT This report has been prepared by the Detroit Wayne County Port Authority and its Director of Economic Development, John Kerr. The following assisted in the project and this report: • Program Managers: SDG Associates LLC assisted by The Mannik & Smith Group. • Architects: Hamilton-Anderson Associates. • Geotechnical, Seawall and Wharf Engineers: NTH • Testing Engineers: NTH • Construction Manager at Risk (CM@R): White-Olson-Korneffel Joint Venture. The Detroit Wayne County Port Authority acknowledges the invaluable assistance on this complex project from the following: • MDOT Central Office, Lansing (Chris Youngs and Kim Johnson) • MDOT Regional Office, Southfield (Vince Ranger) • MDOT Transportation Service Center, Detroit (Victor Judnic succeeded by Tia Klein) • FHWA Lansing Office (Phil Lynwood) Archived December 1, 2012 Page 2 Detroit Wayne County Port Authority NEW PUBLIC DOCK & TERMINAL BUILDING SEP-14 FINAL REPORT SEP-14 FINAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY 2. ABBREVIATIONS AND DEFINITIONS 3. PROJECT BACKGROUND AND HISTORY 4. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 5. FUNDING HISTORY 6. CONSTRUCTION MANAGER PROJECT DELIVERY SYSTEM ALTERNATIVES 7. CONSTRUCTION MANAGER -

CRAIN's LIST: INDUSTRIAL Leasesranked by Square Feet

CRAIN'S LIST: INDUSTRIAL LEASES Ranked by square feet Rank Building Asking rate Owner Tenant Broker Square feet 1. Northline Industrial Center, Romulus $2.85 Northline Comprehensive Logistics Co. B CB Richard Ellis, Colliers 718,684 2. 28301 Schoolcraft Road, Livonia $4.75 Ashley Capital Technicolor Videocassette of Michigan B Ashley Capital 715,096 3. 151 Lafayette, Mt. Clemens $2.00 Steel Pro Metro International Trade Services Signature Associates 674,432 7900 N. Haggerty Road, Canton $4.15 Levco Bay Logistics Co. B Signature Associates, Equity Industrial 442,500 4. L.P. 5. 36501 Van Born Road, Romulus $4.15 Ashley Capital Bay Logistics Co. B Signature Associates 416,487 Pinnacle Logistics Park, Redford $3.95 General Development Co. Technicolor Videocassette of Michigan B Signature Associates, Friedman Real 393,940 6. Estate Group Interchange West Business Center, Van Buren $4.75 Kojaian Management Co. Neapco Driveline L.L.C. CB Richard Ellis, Grubb & Ellis 342,856 7. Township 8. 13600 Fullerton St., Detroit $3.85 Ashley Capital Progressive Distribution Centers Inc. Signature Associates 315,356 9. 4815 Cabot St., Detroit $3.25 Industrial Realty Group Metro International Trade Services Signature Associates 313,388 10. 26195 Bunert Road, Warren $4.75 Ashley Capital Modular Automotive Systems L.L.C. Ashley Capital 276,790 11. 36445 Van Born Road, Romulus $4.15 Ashley Capital Plastipak Packaging Inc. Signature Associates 274,007 12. 36667 Schoolcraft Road, Livonia $2.00 C Kin Properties Inc. NYX Inc. Principal Associates, CB Richard Ellis 252,262 13. 17800 Dix-Toledo Road, Brownstown Township $4.50 Ashley Capital Syncreon US Inc. -

Detroit, Michigan

Detroit Table of Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Detroit in Books, Serials, and Maps ............................................................................................... 5 Books and Serials ........................................................................................................................ 5 Primary Sources ...................................................................................................................... 5 Secondary Sources .................................................................................................................. 6 Detroit in Maps ........................................................................................................................... 7 Early Maps .............................................................................................................................. 7 Physical Features .................................................................................................................... 7 Cultural Features ..................................................................................................................... 8 Early Documents (Before 1850) ................................................................................................... 10