SIGNATURES Wordsworth's Black Combe Poems:The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Troutal Farm Duddon

High Tilberthwaite Farm Troutal Farm Duddon Troutal Farm Thank you for your interest… In what we think is a great opportunity for the right people to work at Troutal Farm in the coming years with us in the National Trust. Since our current tenants gave notice in September 2018, we’ve been working really hard to look at how farming in balance with nature will continue here and how we will work closely with our new tenants to make a successful partnership for everyone. This farm is in an amazing part of the Lake District that is loved by millions – the area is so special that, in 2017, the Lake District became a World Heritage Site as a Cultural Landscape – in no small part due to the way in which people have interacted with and been influenced by the landscape over hundreds of years. Farming has been one of the key elements of this and we are working to help it continue. It’s a time of real change and uncertainty at the moment as Brexit looms and the future is unclear – but we believe that it is also a time of opportunity for you and for us. We are really clear that we want a successful farming enterprise here that also helps us meet our national strategy, our ambition for the land – a shared purpose for the countryside. We know that we can achieve this by working together – through the period of change and uncertainty and beyond into what we hope will be a strong long term relationship. Thank you again for your interest in Troutal Farm. -

Complete 230 Fellranger Tick List A

THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS – PAGE 1 A-F CICERONE Fell name Height Volume Date completed Fell name Height Volume Date completed Allen Crags 784m/2572ft Borrowdale Brock Crags 561m/1841ft Mardale and the Far East Angletarn Pikes 567m/1860ft Mardale and the Far East Broom Fell 511m/1676ft Keswick and the North Ard Crags 581m/1906ft Buttermere Buckbarrow (Corney Fell) 549m/1801ft Coniston Armboth Fell 479m/1572ft Borrowdale Buckbarrow (Wast Water) 430m/1411ft Wasdale Arnison Crag 434m/1424ft Patterdale Calf Crag 537m/1762ft Langdale Arthur’s Pike 533m/1749ft Mardale and the Far East Carl Side 746m/2448ft Keswick and the North Bakestall 673m/2208ft Keswick and the North Carrock Fell 662m/2172ft Keswick and the North Bannerdale Crags 683m/2241ft Keswick and the North Castle Crag 290m/951ft Borrowdale Barf 468m/1535ft Keswick and the North Catbells 451m/1480ft Borrowdale Barrow 456m/1496ft Buttermere Catstycam 890m/2920ft Patterdale Base Brown 646m/2119ft Borrowdale Caudale Moor 764m/2507ft Mardale and the Far East Beda Fell 509m/1670ft Mardale and the Far East Causey Pike 637m/2090ft Buttermere Bell Crags 558m/1831ft Borrowdale Caw 529m/1736ft Coniston Binsey 447m/1467ft Keswick and the North Caw Fell 697m/2287ft Wasdale Birkhouse Moor 718m/2356ft Patterdale Clough Head 726m/2386ft Patterdale Birks 622m/2241ft Patterdale Cold Pike 701m/2300ft Langdale Black Combe 600m/1969ft Coniston Coniston Old Man 803m/2635ft Coniston Black Fell 323m/1060ft Coniston Crag Fell 523m/1716ft Wasdale Blake Fell 573m/1880ft Buttermere Crag Hill 839m/2753ft Buttermere -

Community Led Plan 2019 – 2024

The Community Plan and Action Plan for Millom Without Parish Community Led Plan 2019 – 2024 1 1. About Our Parish Millom Without Parish Council is situated in the Copeland constituency of South West Cumbria. The Parish footprint is both in the Lake District National Park or within what is regarded as the setting of the Lake District National Park. This picturesque area is predominately pastoral farmland, open fell and marshland. Within its boundary are the villages of The Green, The Hill, Lady Hall and Thwaites. On the North West side, shadowed by Black Combe, is the Whicham Valley and to the South the Duddon Estuary. On its borders are the villages of Silecroft, Kirksanton, Haverigg, Broughton in Furness, Foxfield, Kirkby in Furness, Ireleth, Askam and the town of Millom. On the horizon are the Lake District Fells which include Coniston, Langdale and Scafell Ranges and is the gateway to Ulpha, Duddon and Lickle Valleys. Wordsworth wrote extensively of the Duddon, a river he knew and loved from his early years. The Parish has approximately 900 Residents. The main industry in this and surrounding areas is tourism and its relevant services. Farming is also predominant and in Millom there are a number of small industrial units. The Parish is also home to Ghyll Scaur Quarry. 2. Our Heritage Millom Without is rich in sites of both historic and environmental interest. Historic features include an important and spectacular bronze age stone circle at Swinside, the Duddon Iron furnace, and Duddon Bridge. The landscape of Millom Without includes the Duddon estuary and the views up to the Western and Central Lake District Fells. -

A Tectonic History of Northwest England

A tectonic history of northwest England FRANK MOSELEY CONTENTS Introduction 56x Caledonian earth movements 562 (A) Skiddaw Slate structures . 562 (B) Borrowdale Volcanic structures . 570 (C) Deformation of the Coniston Limestone and Silurian rocks 574 (D) Comment on Ingleton-Austwick inlier 580 Variscan earth movements. 580 (A) General . 580 (B) Folds 584 (C) Fractures. 587 4 Post Triassic (Alpine) earth movements 589 5 References 59 ° SUMMARY Northwest England has been affected by the generally northerly and could be posthumous Caledonian, Variscan and Alpine orogenies upon a pre,Cambrian basement. The end- no one of which is entirely unrelated to the Silurian structures include early N--S and later others. Each successive phase is partially NE to ~NE folding. dependent on earlier ones, whilst structures The Variscan structures are in part deter- in older rocks became modified by succeeding mined by locations of the older massifs and in events. There is thus an evolutionary structural part they are likely to be posthumous upon sequence, probably originating in a pre- older structures with important N-S and N~. Cambrian basement and extending to the elements. Caledonian wrench faults were present. reactivated, largely with dip slip movement. The Caledonian episodes are subdivided into The more gentle Alpine structures also pre-Borrowdale Volcanic, pre-Caradoc and follow the older trends with a N-s axis of warp end-Silurian phases. The recent suggestions of or tilt and substantial block faulting. The latter a severe pre-Borrowdale volcanic orogeny are was a reactivation of older fault lines and rejected but there is a recognizable angular resulted in uplift of the old north Pennine unconformity at the base of the volcanic rocks. -

RR 01 07 Lake District Report.Qxp

A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas Integrated Geoscience Surveys (North) Programme Research Report RR/01/07 NAVIGATION HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT Bookmarks The main elements of the table of contents are bookmarked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub-headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. In addition, the report contains links: from the principal section and subsection headings back to the contents page, from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, from each figure, plate or table caption to the first place that figure, plate or table is mentioned in the text and from each page number back to the contents page. RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RESEARCH REPORT RR/01/07 A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the District and adjacent areas Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2004. D Millward Keywords Lake District, Lower Palaeozoic, Ordovician, Devonian, volcanic geology, intrusive rocks Front cover View over the Scafell Caldera. BGS Photo D4011. Bibliographical reference MILLWARD, D. 2004. A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas. British Geological Survey Research Report RR/01/07 54pp. -

The 'Taint of Sordid Industry'

The ‘Taint of Sordid Industry’: Nicholson and Wordsworth Christopher Donaldson Nicholson was, in the main, deferential towards William Wordsworth as a literary forebear. But he was nevertheless outspokenly critical of Wordsworth’s condemnation of the development of heavy industry in and around the Lake District. Nicholson’s engagement with Wordsworth’s River Duddon sonnets is indicative. I refer, of course, to Nicholson’s chiding of the Romantic poet’s description of the Duddon as being ‘remote from every taint | Of sordid industry’.1 Comet readers will remember Nicholson’s response to these lines in his poem ‘To the River Duddon’. There the poet recalls the ‘nearly thirty years’ he has lived near the Duddon in order to challenge Wordsworth’s account of the river as an idyllic stream. Instead, he writes from personal experience of the Duddon as an industrial waterway: one whereon ‘slagbanks slant | Like screes sheer into the sand,’ and where ‘the tide’ runs ‘Purple with ore back up the muddy gullies’.2 Historically speaking, Nicholson is right. Even in Wordsworth’s time, the Duddon was a river shaped and tinctured by charcoal making and iron mining, among other industries. Yet, as David Cooper has noted, Nicholson’s rebuff to Wordsworth in ‘To the River Duddon’ is couched not in historical terms but in personal ones.3 The power of this poem is rooted in its use of autobiographical perspective. It is to his life-long familiarity with the Duddon that Nicholson appeals in order to challenge his Romantic precursor’s characterisation of the river. This challenge to Wordsworth echoes previous attacks on the Duddon sonnets. -

Next Championship Races

The ‘CFR 30th Anniversary ’- by Tom Chatterley (report below) Cumberland Fell Runners Newsletter- WINTER 2016-17 Welcome to the first newsletter of 2017. There is plenty to read and think about in this issue. Thank you to all contributors. You can find more about our club on our website www.c-f-r.org.uk , Facebook & Twitter. In this issue. Did you know ? –LOST on BLACKCOMBE .Photo Quiz –Jim Fairey Club Meeting news-Jenny Chatterley Winter League Winners –Jane Mottram Next Championship Races Book Club –Paul Johnson Club Kit- Ryan Crellin Juniors News Club Runs WANTED! –Volunteers CFR 30th Anniversary –Jane Mottram Wasdale Wombling- Lindsay Buck CFR at 30- Barry Johnson Race Reports Blake,-Crummock, Jarret’s Jaunt, Carrock, Long Mynd.. Feature Race - Eskdale Elevation – David Jones Other News. View from Latrigg –by Sandra Mason Did You Know!— LOST on BLACK COMBE !!! Several members went walkabout on the Black Combe fell race ! Not surprising as the mist was down to the bottom of the fell! Interesting screen shot from Strava of the flybys from our club... no naming and shaming here though! And... a faithful CFR dog also found himself lost and was rescued by another brave CFR dog! And ... someone lost/forgot their dibber! And... Two club members lost their car after navigating the course perfectly! And...someone lost the contents of their stomach on the way home! Claire and Jennie --‘You did what !!’ Some of the members home safe . Are the others still out there or hiding in shame? Club Meeting Summary Tuesday 14th March –by Jennie Chatterley, Club Secretary Charlotte Akam Matthew Aleixo Nick Moore- Chair Colin Burgess Tamsin Cass Kate Beaty- Treasurer Jenny Jennings Ryan Hutchinson Jennie Chatterley- Secretary Peter Mcavoy Andy Ross Paul Jennings- Membership and website Rosie Watson Andy Bradley- Statistician Official welcome to Hannah & Jen Bradley - Dot Patton- Newsletter completing the full Bradley family as CFR competing Jane Mottram- Press officer members. -

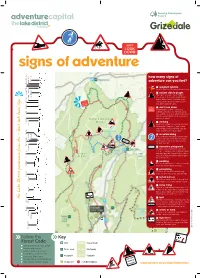

Grizedale Leaflet Innerawk)

DON’T LOOK DOWN signs of adventure how many signs of Harter Fell adventure can you find? Mardale Ill Bell Mardale Thonthwaite Crag spaghetti junction Ignore the directions of the signs and keep on going. Red Screes Red not just elderly people Caudale Moor That’s right…we mean Coniston Old Man! Scandale Pass There is more to the Adventure Capital than fell walking. Want a change? Try mountain biking, Dove Crag DON’T climbing, horse riding or even a hot air balloon Hart Crag LOOK for a different view of the Lakes. DOWN sign ’ DON’T don’t look down Fairfield n LOOK And why would you? With countless walks, DOWN scrambles and climbs in the Adventure Capital the possibilities are endless. Admire the panorama, Helvellyn familiarise yourself with the fell names and choose which one to explore! climbing Helm Crag t look dow Known as the birthplace of modern rock climbing Steel Fell ’ following Walter Parry Haskett Smith’s daring n ascent of Napes Needle in 1884 the Adventure do Capital is home to some classic climbs. ‘ High Raise mountain biking Hours can be spent exploring the network of trails Pavey Ark Pavey and bridleways that cover the Adventure Capital. Holme Fell A perfect place to start is Grizedale’s very own The North Face Trail. Harrison Stickle adventure playground The natural features that make the Lake District Pike of Stickle Pike scenery so stunning also make it a brilliant natural adventure playground. Conquer the fells, scale the crags, hit the trails and paddle or swim the Lakes Pike of Blisco Pike that make it famous. -

February 2008: the Christmas Issue. New Year, New Races

NewsieBlack Combe Runners February 2008: the Christmas issue. New year, new races. New beer. It came as a shock when Will asked me for some words for the Newsie, as I was now Club Captain, but knowing I can’t wriggle out, here they are. Firstly, thanks to those at the AGM for your show of faith in me seeing that I’ve only been in the club a year, and thanks to Penny for her support as Captain. Both Hazel and I have been really pleased with the reception and friendliness of all in the club over the last year and it has made a huge difference to the enjoyment we’ve had running. We all run for fun, for some it is running and chatting on a Tuesday night, for others it is racing and drinking as much as is financially viable at the weekend. Our aim has to be to maintain this and help people to take part and stretch themselves when and where they want to. This photograph was taken by Dave Watson. That’s the only explanation I can offer. Ed. The winter league races, excellently organised by Val with her mallet, have attracted a lot of interest with 26 people We had 9 wanting to run last year so it’s a reasonable having competed in the first four races, most having hope. As a number of us found out in running it for the run two or more. The overall result is still wide open, first time in 2007, it’s a great team day out, with a little particularly as Val hasn’t told us how she will handicap us running thrown in and a few beers afterwards. -

Back Matter (PDF)

Index Note: Page numbers in italic type refer to illustrations; those in bold type refer to tables. Acadian Orogeny 147, 149 Cambrian-Silurian boundary. 45 occurrence of Skiddaw Slates 209 application to England 149 correspondence 43 thrusting 212 cause of 241 Green on 82 topography 78 cleavage 206,240 Hollows Farm 124 Black Combe sheet 130 deformation 207,210,225,237 Llandovery 46 black lead see graphite and granites 295 maps 40-41 Blackie, Robert 176 and lapetus closure 241,294 portrait 40 Blake Fell Mudstones 55 Westmorland Monocline 233,294 section Plate IV Blakefell Mudstone 115 accessory minerals 96 on unconformity below Coniston Limestone Series 83 Blea Crag 75 accretionary prism model 144, 148, 238 Bleaberry Fell 46 accretionary wedge, Southern Uplands 166, 237 Backside Beck 59.70. 174 Bleawath Formation 276,281 Acidispus 30 backthrusts 225,233,241. 295 Blencathra 162 Acritarchs Bad Step Tuff 218, 220 see also Saddleback Bitter Beck 118 Bailey, Edward B. 85, 196 Blengdale 276 Calder River 198 Bakewell, Robert 7,10 Blisco Formation 228 Caradoc 151 Bala Group 60, 82 Boardman, John 266, 269 Charles Downie on 137 Bala Limestone Bohemian rocks, section by Marr 60 Holehouse Gill 169, 211,221,223 Caradoc 21 Bolton Head Farm 276 Llanvirn 133 and Coniston Limestone 19.22, 23.30 Bolton. John 24, 263 Troutbeck 205 and lreleth Limestone 30 Bonney, Thomas 59 zones 119 Middle Cambrian 61 boreholes 55 Actonian 173, 179 Upper Cambrian 20 Nirex 273 Agassiz, Louis 255,257 Bala unconformity 82, 83.85 pumping tests 283, 286 Agnostus rnorei 29 Ballantrae complex 143 Wensleydale 154 Aik Beck 133 Balmae Beds 36 Borrowdale 9, 212,222 Airy, George 9 Baltica 146, 147, 240. -

Morecambe Bay Estuaries and Catchments

Morecambe Bay estuaries and catchments The group of estuaries that comprise Morecambe Bay form the largest area of intertidal mudflats and sands in the UK. The four rivers discharging into the bay are the Leven (with Crake) and Kent (with Bela) in the North, and Lune and Wyre in the East (Figure 1). Fig 1. The four contributory areas of the estuarine system of Morecambe Bay in Northwest England (below) of the Leven, Kent, Lune and Wyre rivers (left). The neighbouring rivers of the Ribble and South West Lakes region are also shown1 The Leven and Kent basins cover over 1,000 km2 (1,426 km2 when grouped with the neighbouring River Duddon), the Lune 1,223 km2 and Wyre 450 km2, with all draining into Morecambe Bay between the towns of Barrow-in-Furness in the Northwest and Blackpool in the South. The city of Lancaster and towns of Ulverston, Broughton-in-Furness, Ambleside, Windermere, Bowness-on- Windermere, Grange-over-Sands, Sedburgh, Kendal, Kirkby Lonsdale, Ingleton, Carnforth, Morecambe, Garstang, Fleetwood and Blackpool lie within the basins. Leven and Kent basins: River Leven is sourced on both Bow Fell (902 m) at the head of the Langdale Valley and Dollywagon Pike (858 m) above Dunmail Raise. These fells comprise of volcanic rocks of the Borrowdale Volcanic Group that characterise the central Cumbrian Mountains. The source on Bow Fell is only 3 km from the wettest place in the UK with the Sprinkling Tarn raingauge recording 6,528 mm in 1954. Both tributary streams flow through Lake Windermere (Fig. 2) that is England’s largest lake with a surface area of 14.7 km2. -

Cumbria Classified Roads

Cumbria Classified (A,B & C) Roads - Published January 2021 • The list has been prepared using the available information from records compiled by the County Council and is correct to the best of our knowledge. It does not, however, constitute a definitive statement as to the status of any particular highway. • This is not a comprehensive list of the entire highway network in Cumbria although the majority of streets are included for information purposes. • The extent of the highway maintainable at public expense is not available on the list and can only be determined through the search process. • The List of Streets is a live record and is constantly being amended and updated. We update and republish it every 3 months. • Like many rural authorities, where some highways have no name at all, we usually record our information using a road numbering reference system. Street descriptors will be added to the list during the updating process along with any other missing information. • The list does not contain Recorded Public Rights of Way as shown on Cumbria County Council’s 1976 Definitive Map, nor does it contain streets that are privately maintained. • The list is property of Cumbria County Council and is only available to the public for viewing purposes and must not be copied or distributed. A (Principal) Roads STREET NAME/DESCRIPTION LOCALITY DISTRICT ROAD NUMBER Bowness-on-Windermere to A590T via Winster BOWNESS-ON-WINDERMERE SOUTH LAKELAND A5074 A591 to A593 South of Ambleside AMBLESIDE SOUTH LAKELAND A5075 A593 at Torver to A5092 via