Unexplained Wealth Orders Global Lessons for the UK Ahead of Implementation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asset Recovery Handbook

Asset Recovery Handbook eveloping countries lose billions each year through bribery, misappropriation of funds, Dand other corrupt practices. Much of the proceeds of this corruption find “safe haven” in the world’s financial centers. These criminal flows are a drain on social services and economic development programs, contributing to the impoverishment of the world’s poorest countries. Many developing countries have already sought to recover stolen assets. A number of successful high-profile cases with creative international cooperation has demonstrated Asset Recovery Handbook that asset recovery is possible. However, it is highly complex, involving coordination and collaboration with domestic agencies and ministries in multiple jurisdictions, as well as the A Guide for Practitioners, Second Edition capacity to trace and secure assets and pursue various legal options—whether criminal confiscation, non-conviction based confiscation, civil actions, or other alternatives. A Guide for Practitioners, This process can be overwhelming for even the most experienced practitioners. It is exception- ally difficult for those working in the context of failed states, widespread corruption, or limited Jean-Pierre Brun resources. With this in mind, the Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR) Initiative has developed and Anastasia Sotiropoulou updated this Asset Recovery Handbook: A Guide for Practitioners to assist those grappling with Larissa Gray the strategic, organizational, investigative, and legal challenges of recovering stolen assets. Clive Scott A practitioner-led project, the Handbook provides common approaches to recovering stolen assets located in foreign jurisdictions, identifies the challenges that practitioners are likely to Kevin M. Stephenson encounter, and introduces good practices. It includes examples of tools that can be used by Second Edition practitioners, such as sample intelligence reports, applications for court orders, and mutual legal assistance requests. -

Code of Practice Issued Under Section 377 of Thye Proceeds Of

CODE OF PRACTICE ISSUED UNDER SECTION 377 OF THE PROCEEDS OF CRIME ACT 2002 Investigations January 2018 CCS1017189378 978-1-5286-0076-7 CODE OF PRACTICE ISSUED UNDER SECTION 377 OF THE PROCEEDS OF CRIME ACT 2002 Investigations January 2018 © Crown copyright 2018 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at Criminal Finances Team Home Office 6th Floor Peel Building 2 Marsham Street LONDON SW1P 4DF Contents Abbreviations used in this code 1 Introduction 1 Appropriate officers and appropriate persons 3 General provisions relating to all orders and warrants 6 Action to be taken before an application is made 6 Reasonable grounds for suspicion 8 Action to be taken in making an application 9 Action to be taken in serving an order or warrant 11 Action to be taken in receiving an application for an extension of a time limit 14 Record of Proceedings 14 Retention of documents and information 15 Variation and discharge application 15 Production orders 16 Definition 16 Persons who can apply for a production order 16 Statutory requirements 16 Particular action to be taken -

Unexplained Wealth Orders and Account Freezing Orders – a Year On

The Law Society UNEXPLAINED WEALTH ORDERS AND ACCOUNT FREEZING ORDERS – A YEAR ON Michael Potts Byrne and Partners LLP Ross Dixon Hickman & Rose The Law Society Contents 1 UWO’s – the law 2 UWO’s – 1+ year on 3 Reluctance of Enforcement Authorities to use UWO’s. 4 What have we learned from Respondent’s challenges? 5 What for the future of UWO’s? 6 AFOs - the law 7 AFOs – 1+ year on 8 AFOs – the future The Law Society Unexplained Wealth Orders – the law The Law Society What is a UWO and what is the law on obtaining an order? What is an Unexplained Wealth Order (“UWO”)? The law on obtaining a UWO? • The Unexplained Wealth Order (“UWO”) is a civil • An application is made to the High Court if an investigation tool requiring either a Politically Exposed enforcement authority has reasonable cause to believe Person (“PEP”) or a person suspected of involvement in that a person holds unexplained property in excess of £50,000 and they are either: serious crime (or association with it), to disclose assets that appear disproportionate to their known legitimate income. It is not a determination that property was • Any non - EU PEP or a person closely associated or obtained as a result of criminal conduct. connected with a PEP (including family); or • that there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that person is or has been involved in serious crime (in the UK or elsewhere) or is connected with such a person. Serious • A UWO is only available to the following identified crime as defined includes money laundering, bribery and enforcement authorities: corruption, slavery, people trafficking, drug trafficking and other offences • the National Crime Agency • Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs • The enforcement agency must prove that there are • the Financial Conduct Authority reasonable grounds for suspecting that the known • the Director of the Serious Fraud Office sources of the individual’s lawfully obtained income • the Crown Prosecution Service would have been insufficient for the purposes of enabling them to obtain the property in question. -

Laundromats: Responding to New Challenges in the International Fight Against Organised Crime, Corruption and Money-Laundering

Provisional version Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Laundromats: responding to new challenges in the international fight against organised crime, corruption and money-laundering Report* Rapporteur: Mr Mart van de VEN, Netherlands, Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe A. Draft resolution 1. The Assembly is deeply concerned by the extent of money-laundering involving Council of Europe member States. The ‘Global Laundromat’, by which at least $21 billion and perhaps as much as $80 billion was illegally transferred from Russia to recipients around the world, and the ‘Azerbaijani Laundromat’, by which $2.9 billion was moved out of Azerbaijan, are the most alarming recent examples. Money laundering, especially on this scale, is a serious threat to democratic stability, human rights and the rule of law in the countries from, through and to which illicit funds are transferred, amongst other things by facilitating, encouraging and concealing corruption and other serious criminal activity. 2. The Global Laundromat was made possible by serious structural issues, at various levels. It originated in the desire of Russian businessmen, organised criminals and, apparently, interests connected to state organs (notably the Federal Security Service, FSB) to illicitly transfer huge amounts of money out of the country, at minimal transaction cost. It typically depended upon corruption in the Moldovan judicial and banking systems; the opaque beneficial ownership of shell companies, often based in the UK or its Overseas Territories; and failures and inadequacies in the anti-money laundering (AML) systems of many banks, especially ABLV bank in Latvia, along with ineffective national AML supervisory regimes. Despite some encouraging developments in the Republic of Moldova and the promise of an investigation in the UK, the Global Laundromat has still not been subject to proper criminal investigation. -

Reaching the Unreachable Attacking the Assets of Serious and Organised Criminality in the UK in the Absence of a Conviction

Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies Occasional Paper Reaching the Unreachable Attacking the Assets of Serious and Organised Criminality in the UK in the Absence of a Conviction Helena Wood Reaching the Unreachable Attacking the Assets of Serious and Organised Criminality in the UK in the Absence of a Conviction Helena Wood RUSI Occasional Paper, June 2019 Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies ii Reaching the Unreachable 188 years of independent thinking on defence and security The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) is the world’s oldest and the UK’s leading defence and security think tank. Its mission is to inform, influence and enhance public debate on a safer and more stable world. RUSI is a research-led institute, producing independent, practical and innovative analysis to address today’s complex challenges. Since its foundation in 1831, RUSI has relied on its members to support its activities. Together with revenue from research, publications and conferences, RUSI has sustained its political independence for 188 years. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not reflect the views of RUSI or any other institution. Published in 2019 by the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Non-Commercial – No-Derivatives 4.0 International Licence. For more information, see <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/>. RUSI Occasional Paper, June 2019. ISSN 2397-0286. Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies Whitehall London SW1A 2ET United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7747 2600 www.rusi.org RUSI is a registered charity (No. -

Unexplained Wealth Orders (Uwos) and Relevant International Experience

Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Background ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Objective ................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3. Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 3 1.4. RUSI’s Expertise....................................................................................................................... 4 1.5. Structure ................................................................................................................................. 5 2. UK’s UWOs in Brief .......................................................................................................................... 5 3. UK’s Introduction of UWOs ............................................................................................................. 6 3.1. Domestic Background ............................................................................................................. 6 3.1.1. Challenges of the UK’s Confiscation Regime .................................................................. 7 3.1.2. Challenges of the UK’s SAR Regime ................................................................................ 8 -

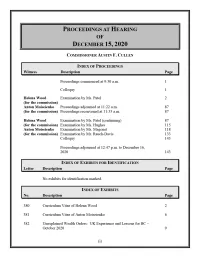

Transcript December 15, 2020.Pdf

Colloquy 1 1 December 15, 2020 2 (Via Videoconference) 3 (PROCEEDINGS COMMENCED AT 9:30 A.M.) 4 THE REGISTRAR: Good morning. The hearing is now 5 resumed, Mr. Commissioner. 6 THE COMMISSIONER: Yes, thank you, Madam Registrar. 7 Ms. Patel, do you have conduct of this 8 portion of the hearing? 9 MS. PATEL: Yes. Thank you, Mr. Commissioner. Today 10 we are hearing from two witnesses who are based 11 in the UK, Helena Wood and Anton Moiseienko of 12 the Royal United Service Institute. 13 THE COMMISSIONER: Yes. 14 MS. PATEL: They're both prepared to affirm. 15 THE COMMISSIONER: Thank you. 16 THE REGISTRAR: Can each of you please state your 17 full name and spell your first name and last 18 name for the record. I will start with 19 Ms. Wood. 20 MS. WOOD: Hello. I'm Helena Wood. My first name is 21 H-e-l-e-n-a, and my surname is W-o-o-d. 22 THE REGISTRAR: Thank you. And Mr. Moiseienko. 23 MR. MOISEIENKO: Hello. I'm Anton Moiseienko. First 24 name A-n-t-o-n, surname, M-o-i-s-e-i-e-n-k-o. 25 Helena Wood (for the commission) 2 Anton Moiseienko (for the commission) Exam by Ms. Patel 1 HELENA WOOD, a witness 2 called for the 3 commission, affirmed. 4 ANTON MOISEIENKO, a 5 witness called for the 6 commission, affirmed. 7 THE COMMISSIONER: Ms. Patel. 8 MS. PATEL: Thank you, Mr. Commissioner. 9 Madam Registrar, if we can please pull up 10 Ms. -

The Practitioner's Guide to Global Investigations

GIR Volume I: Global Investigations in the United Kingdom and the United States Kingdom and the United in the United Investigations I: Global Volume Investigations Global Guide to Practitioner’s The Global Investigations Review The law and practice of international investigations Global Investigations Review TheGIR The law and practiPractitioner’sce of iinnternatiternatioonalnal investigationsinvestigations Guide to Global Investigations Volume I: Global Investigations in the United Kingdom and the United States Fifth Edition Editors Judith Seddon, Eleanor Davison, Christopher J Morvillo, Michael Bowes QC, Luke Tolaini, Ama A Adams, Tara McGrath Fifth Edition 2021 2021 © Law Business Research 2021 The Practitioner’s Guide to Global Investigations Fifth Edition Editors Judith Seddon Eleanor Davison Christopher J Morvillo Michael Bowes QC Luke Tolaini Ama A Adams Tara McGrath © Law Business Research 2021 Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London Meridian House, 34-35 Farringdon Street, London, EC4A 4HL, UK © 2020 Law Business Research Ltd www.globalinvestigationsreview.com No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specific situation, nor does it necessarily represent the views of authors’ firms or their clients. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publishers accept no responsibility for any acts or omissions contained herein. Although the information provided -

Unexplained Wealth Orders 3

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 9098, 8 January 2021 Unexplained Wealth By Ali Shalchi Orders Contents: 1. Background 2. Unexplained Wealth Orders 3. Commentary www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Unexplained Wealth Orders Contents Summary 3 1. Background 4 The pre-2002 position 4 Civil recovery orders 4 The path to Unexplained Wealth Orders 6 2. Unexplained Wealth Orders 8 Who can obtain a UWO? 8 Against whom can a UWO be obtained? 8 How is a UWO obtained? 9 What is a UWO? 10 Interim freezing orders 10 Failure to comply 10 Criminal offence: false statements 11 3. Commentary 12 The first UWO 12 The first recovery of assets 12 The first failed application 13 Number of UWOs used 13 Criticism 14 International comparisons 15 Cover page image copyright: Wendy Wilson 3 Commons Library Briefing, 8 January 2021 Summary For some time the UK has been accused of being a hub for dirty money - especially London’s prime property market. The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 introduced Civil Recovery Orders (CROs) to help tackle the problem. CROs permitted the confiscation of criminal property using a lower “civil” standard of proof. Instead of needing to prove a crime was committed, law enforcement bodies only needed to show a court that on the balance of probabilities (or “more likely that not”) unlawful conduct had occurred, and the property was obtained as a result of that unlawful conduct. However, use of CROs was limited to exceptional cases where the prospect of criminal prosecution was unavailable or undesirable.