Transparency in the Court of Protection Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women Readers of Middle Temple Celebrating 100 Years of Women at Middle Temple the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple Middle Society Honourable the The of 2019 Issue 59 Michaelmas 2019 Issue 59 Women Readers of Middle Temple Celebrating 100 Years of Women at Middle Temple The Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales Practice Note (Relevance of Law Reporting) [2019] ICLR 1 Catchwords — Indexing of case law — Structured taxonomy of subject matter — Identification of legal issues raised in particular cases — Legal and factual context — “Words and phrases” con- strued — Relevant legislation — European and International instruments The common law, whose origins were said to date from the reign of King Henry II, was based on the notion of a single set of laws consistently applied across the whole of England and Wales. A key element in its consistency was the principle of stare decisis, according to which decisions of the senior courts created binding precedents to be followed by courts of equal or lower status in later cases. In order to follow a precedent, the courts first needed to be aware of its existence, which in turn meant that it had to be recorded and published in some way. Reporting of cases began in the form of the Year Books, which in the 16th century gave way to the publication of cases by individual reporters, known collectively as the Nominate Reports. However, by the middle of the 19th century, the variety of reports and the variability of their quality were such as to provoke increasing criticism from senior practitioners and the judiciary. The solution proposed was the establishment of a body, backed by the Inns of Court and the Law Society, which would be responsible for the publication of accurate coverage of the decisions of senior courts in England and Wales. -

2017 Magdalen College Record

Magdalen College Record Magdalen College Record 2017 2017 Conference Facilities at Magdalen¢ We are delighted that many members come back to Magdalen for their wedding (exclusive to members), celebration dinner or to hold a conference. We play host to associations and organizations as well as commercial conferences, whilst also accommodating summer schools. The Grove Auditorium seats 160 and has full (HD) projection fa- cilities, and events are supported by our audio-visual technician. We also cater for a similar number in Hall for meals and special banquets. The New Room is available throughout the year for private dining for The cover photograph a minimum of 20, and maximum of 44. was taken by Marcin Sliwa Catherine Hughes or Penny Johnson would be pleased to discuss your requirements, available dates and charges. Please contact the Conference and Accommodation Office at [email protected] Further information is also available at www.magd.ox.ac.uk/conferences For general enquiries on Alumni Events, please contact the Devel- opment Office at [email protected] Magdalen College Record 2017 he Magdalen College Record is published annually, and is circu- Tlated to all members of the College, past and present. If your contact details have changed, please let us know either by writ- ing to the Development Office, Magdalen College, Oxford, OX1 4AU, or by emailing [email protected] General correspondence concerning the Record should be sent to the Editor, Magdalen College Record, Magdalen College, Ox- ford, OX1 4AU, or, preferably, by email to [email protected]. -

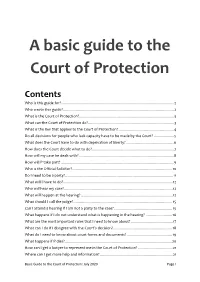

A Basic Guide to the Court of Protection

A basic guide to the Court of Protection Contents Who is this guide for? ................................................................................................................ 2 Who wrote this guide? .............................................................................................................. 2 What is the Court of Protection? .............................................................................................. 3 What can the Court of Protection do? ..................................................................................... 3 What is the law that applies to the Court of Protection? ....................................................... 4 Do all decisions for people who lack capacity have to be made by the Court? .................... 5 What does the Court have to do with deprivation of liberty? ................................................ 6 How does the Court decide what to do? ................................................................................. 7 How will my case be dealt with? .............................................................................................. 8 How will P take part? ................................................................................................................ 9 Who is the Official Solicitor? ................................................................................................... 10 Do I need to be a party? ........................................................................................................... 11 -

4 PAPER BUILDINGS Court of Protection Seminar

4 PAPER BUILDINGS Court of Protection Seminar 5th May 2011 CHAIR Robin Barda TOPICS & SPEAKERS : Court of Protection - Welfare Sally Bradley The Property and Affairs of Mentally Incapacitated Adults: Cases of Interest Following The Coming Into Force of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 James Copley A Mediation process for Court of Protection Matters Angela Lake-Carroll The Chambers of Jonathan Cohen QC INDEX 1. 4 Paper Buildings: Who we are 2. Court of Protection - Welfare Sally Bradley 3. The Property and Affairs of Mentally Incapacitated Adults: -Cases of Interest Following The Coming Into Force of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 James Copley 4. A Mediation process for Court of Protection Matters Angela Lake-Carroll 5. Court of Protection Handout & Crib Sheet (notes only) Henry Clayton 6. Profiles of the speakers 7. Members of Chambers Section 1 4 Paper Buildings: Who we are The Chambers of Jonathan Cohen QC 4 Paper Buildings “This dedicated family set has expanded rapidly in recent years and now has a large number of the leading players in the field.” Chambers UK 2010 At 4 Paper Buildings, Head of Chambers Jonathan Cohen QC has 'developed a really strong team across the board'. 'There is now a large number of specialist family lawyers who provide a real in-depth service on all family matters.' The 'excellent' 4 Paper Buildings 'clerks are very helpful' and endeavor to solve problems, offering quality alternatives if the chosen counsel is not available.' Legal 500 2010 “4 Paper Buildings covers a broad spectrum of civil and family matters. On the family front its best known for its children- related work, although its reputation does extend to matrimonial finance work as well”. -

Cardiff & District Annual Dinner

THE MAGAZINE OF THE CONFEDERATION OF THE SOUTH WALES LAW SOCIETIES LEGAL NEWS Cardiff & District Annual Dinner Booking form on page 10 DECEMBER 2008 Editorial Board Richard Fisher - Editor Michael Walters - Secretary Gaynor Davies CONTENTS David Dixon Philip Griffith 3 CARDIFF & DISTRICT Simon Mumford President’s Letter Editorial copy to . Richard Fisher Charles Crooke 4 FEATURE 51 The Parade Are Some Firms Now Uninsurable? Cardiff CF24 3AB Tel: 029 2049 1271 . Fax: 029 2047 1211 DX 33025 Cardiff 1 5 FEATURE E-mail [email protected] The Coroner’s Tale - Lord Justice Scott Baker on the Diana Inquest . Designed and Produced by PW Media & Publishing Ltd 6 PRESIDENT’S REPORT Tel: 01905 723011 Simon Mumford - December 2008 Managing Editor . Dawn Pardoe Graphic Design 8 UPDATES Paul Blyth Election Fever and Three Courts Walk . Advertising Sales Alison Jones 10 ANNUAL DINNER Email: [email protected] Booking Form Printed By . Stephens & George 11 FREE MEMBERSHIP The articles published in Legal News South West Confederation of Law Societies represent the views of the contributor and are not necessarily the official . views of the Confederation of South Wales Law Societies, Cardiff & District 12 REGULATION Law Society, or of the Editorial Board. Open Day at SRA The magazine or members of the . Editorial Board are in no way liable for such opinions. Whilst every care has 13 MEMBERSHIP MATTERS been taken to ensure that the contents of this issue are accurate, we cannot be It’s Time to Renew Your Membership held responsible for any inaccuracies or . late changes. No article, advertisement or graphic, in whole or in print, may be 14 REGULATION reproduced without written permission Practice Standards Unit - Friend, Foe or Phony? of the publishers. -

Court of Handbook Protection

Court of Court of Court of Court of Protection Protection Protection Protection Court of Court of Court of Court of Protection Protection Protection Protection SUPPLEMENT TO THE SECOND EDITION Court of Court of Protection Protection Handbook Handbook a user’s guide Alex Ruck Keene, Kate Edwards, Professor Anselm Eldergill and Sophy Miles Cover design by Tom Keates the access to the access to justice charity justice charity courtofprotectionhandbook.com Court of Protection Handbook is supported by courtofprotectionhandbook.com On the site, you will find: • links to relevant statutory materials and other guidance that space precluded us from including in the appendices; • precedent orders covering the most common situations that arise before the court; • useful (free) web resources; and • updates on practice and procedure before the Court of Protection. These updates take the form of posts on the site’s blog, and also (where relevant) updates cross-referenced to the relevant paragraphs in the book. ThisRegist supplementer to receive toemail Courtup ofdat Protectiones at www Handbook.courtofprot includesectionhandb theoo Courtk.com of Protection Rules 2017 and commentary from the authors highlighting Follow us on Twitter @COPhandbook developments since the second edition. Readers also have access to courtofprotectionhandbook.com which provides regular updates on practice and procedure before the Court of Protection cross-referenced to the relevant parts of the book, together with links to all the relevant statutory materials and guidance. A revised second edition of Court of Protection Handbook which incorporates this supplementary material and the new rules in a single volume of the work is available: Pb 978 1 912273 10 2 / December 2017 / £65 Order at lag.org.uk Phone 01235 465577 Email [email protected] Available as an ebook at www.lag.org.uk/ebooks The purpose of Legal Action Group is to promote equal access to justice for all members of society who are socially, economically or otherwise disadvantaged. -

Formal Minutes of the Joint Committee on Human Rights – Session 2019-21

Formal minutes of the Joint Committee on Human Rights – Session 2019-21 Wednesday 4 March 2020 Members present: Lord Brabazon of Tara Fiona Bruce MP Lord Dubs Ms Karen Buck MP Baroness Massey of Darwen Joanna Cherry MP Lord Singh of Wimbledon Ms Harriet Harman MP Lord Trimble Mrs Pauline Latham MP Dean Russell MP 1. Declaration of interests Members declared their interests (see Appendix). Members declared their interests, in accordance with the Resolution of the House of 13 July 1992 (see Appendix). 2. Election of Chair Ms Harriet Harman MP was called to the Chair. Ordered, That the Chair report her election to the House of Commons. 3. Confidentiality and priviledge The Committee considered this matter. 4. Procedural and administrative matters The Committee considered this matter. Resolved, That the Committee examine witnesses in public, except where it otherwise orders. Resolved, That witnesses who submit written evidence to the Committee are authorised to publish it on their own account in accordance with Standing Order No. 135, subject always to the discretion of the Chair or where the Committee otherwise orders. Resolved, That where the Committee has evidence, including sent or received correspondence, which, in the Chair's judgement, merits publication by the Committee before it will meet again, the Chair shall have discretion to report it to the House for publication. 5. Publication of submission from Government departments The Committee considered this matter. 6. Future programme The Committee considered this matter. [Adjourned till Wednesday 11 March 2020 at 3.00pm Joint Committee on Human Rights – Formal Minutes Appendix Bruce, Fiona (Congleton) Bruce, Fiona (Congleton) 1. -

Court of Protection Annual Update 16Th October 2018 At

#5sblaw Court of Protection Annual Update 16th October 2018 at Prince Philip House 3 Carlton Terrace London SW1 5DG www.5sblaw.com 2.5 hours 8.30 am Registration and breakfast 9.00 am Introduction – David Rees QC 9.05 am Recent deputyship cases – (Re Appointment of Trust Corporations as Deputies; Re AR) Alexander Drapkin and Mathew Roper 9.30 am Problems with Lasting Powers of Attorney – Re The Public Guardian’s Severance Applications Thomas Entwistle 9.50 am Dispute Resolution in and out of the Court of Protection Barbara Rich 10.15 am Coffee 10.45 am Personal Welfare for the Property and Affairs Practitioner David Rees QC 11.15 am Statutory wills and working with the Official Solicitor Jordan Holland 11.35 am Removing defaulting deputies and attorneys William East and Eliza Eagling 12.00 pm Plenary Session 12.30 pm Close David Rees QC is well known for his experience in wills, trusts, estates and Court of Protection matters. He is ranked for Traditional Chancery and Court of Protection in Chambers UK Bar Guide 2018 where he is described as “experienced, knowledgeable and an expert in his field”. He is regularly instructed by the Official Solicitor and appears before all levels of judge in the Court of Protection. He has appeared in many leading cases under the Mental Capacity Act 2005. His recent cases include: The Public Guardian v DA & Others [2018] EWCOP 26 (Test case on the severance of provisions relating to the termination of life in lasting powers of attorney). PBC v JMA & Others [2018] EWCOP 19 (Authorisation of statutory gifts in excess of £6M). -

VICTORIAN BAR NEWS WINTER 2021 ISSUE 169 WINTER 2021 VICTORIAN BAR Editorial

169 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS BAR VICTORIAN ISSUE 169 WINTER 2021 Sexual The Annual Bar VICTORIAN Harassment: Dinner is back! It’s still happening BAR By Rachel Doyle SC NEWS WINTER 2021 169 Plus: Vale Peter Heerey AM QC, founder of Bar News ISSUE 169 WINTER 2021 VICTORIAN BAR editorial NEWS 50 Evidence law and the mess we Editorial are in GEOFFREY GIBSON Not wasting a moment 5 54 Amending the national anthem of our freedoms —from words of exclusion THE EDITORS to inclusion: An interview with Letters to the Editors 7 the Hon Peter Vickery QC President’s message 10 ARNOLD DIX We are Australia’s only specialist broker CHRISTOPHER BLANDEN 60 2021 National Conference Finance tailored RE-EMERGE 2021 for lawyers. With access to all major lenders Around Town and private banks, we’ll secure the best The 2021 Victorian Bar Dinner 12 Introspectives JUSTIN WHEELAHAN for legal professionals home loan tailored for you. 12 62 Choices ASHLEY HALPHEN Surviving the pandemic— 16 64 Learning to Fail JOHN HEARD Lorne hosts the Criminal Bar CAMPBELL THOMSON 68 International arbitration during Covid-19 MATTHEW HARVEY 2021 Victorian Bar Pro 18 Bono Awards Ceremony 70 My close encounters with Nobel CHRISTOPHER LUM AND Prize winners GRAHAM ROBERTSON CHARLIE MORSHEAD 72 An encounter with an elected judge Moving Pictures: Shaun Gladwell’s 20 in the Deep South portrait of Allan Myers AC QC ROBERT LARKINS SIOBHAN RYAN Bar Lore Ful Page Ad Readers’ Digest 23 TEMPLE SAVILLE, HADI MAZLOUM 74 No Greater Love: James Gilbert AND VERONICA HOLT Mann – Bar Roll 333 34 BY JOSEPH SANTAMARIA -

The UK and the European Court of Human Rights

Equality and Human Rights Commission Research report 83 The UK and the European Court of Human Rights Alice Donald, Jane Gordon and Philip Leach Human Rights and Social Justice Research Institute London Metropolitan University The UK and the European Court of Human Rights Alice Donald, Jane Gordon and Philip Leach Human Rights and Social Justice Research Institute London Metropolitan University © Equality and Human Rights Commission 2012 First published Spring 2012 ISBN 978 1 84206 434 4 Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series The Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series publishes research carried out for the Commission by commissioned researchers. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Commission. The Commission is publishing the report as a contribution to discussion and debate. Please contact the Research Team for further information about other Commission research reports, or visit our website: Research Team Equality and Human Rights Commission Arndale House The Arndale Centre Manchester M4 3AQ Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0161 829 8500 Website: www.equalityhumanrights.com You can download a copy of this report as a PDF from our website: http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/ If you require this publication in an alternative format, please contact the Communications Team to discuss your needs at: [email protected] Contents Page Tables i Acknowledgments ii Abbreviations iii Executive summary v 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Aims of the report 1 1.2 Context of the report 1 1.3 Methodology 3 1.4 Scope of the report 4 1.5 Guide to the report 5 2. -

Barristers ' Clerks the Law's Middlemetr John A

JOHN A. FLOOD Barristers ' clerks The law's middlemetr John A. Flood BARRISTERS' CLERKS THE LAW'S MIDDLEMEN Manchester University Press Copyright @John Anthony Flood 1983 Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road. Manchester M13 9PL, UK 51 Washington Street, Dover, N.H. 03820, USA British Library cataloguing in publication data Flood. John A. Barristers' clerks. 1. Legal assistant-England I. Title 340 KD654 ISBN 0-7190-0928-6 Library of Congress utaloging in publication data Flood, John A. Barristers' clerks. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1.Legal assistants-Great Britain. I. Title KD463.F58 1983 347.42'016 8S912 ISBN 0-7190-0928-6 344.2071 6 Printed in Great Britain by Redwood Burn Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire CONTENTS Acknowledgements page vii Chapter 1 Background to the research 1 2 Career patterns and contingencies 15 3 The clerk and his barrister 34 4 Sources of work and relations with solicitors 65 5 Scheduling court cases 85 6 The social world of barristers' clerks The Barristers' Clerks' ~ssociation Conclusion Biography of a research project Solicitors' responses to requests for payment of counsel's fees BCA examination papers Bibliography Index ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In producing this book, and the thesis from which it derives, I have incurred many debts. I would like to thank those who generously helped: William L. Twining, Anthony Bradley, Barbara Harrell-Bond, Luke C. Harris, John P. Heinz, Spencer L. Kimball, Geoffrey Wilson and David Farrier. I am also grateful to the Barristers' Clerks' Association for permission to reproduce their examination papers; and to its officers, past and present, for their assistance and permission to reproduce from their papers: they are Sydney G. -

English for Law Students (Part 1).Pdf

ENGLISH for Law Students in two parts Part 1 Minsk BSU 1999 Учебник английского языка для студентов-юристов в двух частях Часть 1 Минск БГУ 1999 Рецензент: Л.М. Лещева, доктор филологических наук, профессор кафедры лексикологии английского языка Минского государственного лингвистического университета Утверждено на заседании кафедры английского языка гуманитарных факультетов Белгосуниверситета 3 ноября 1998 г., протокол № 3 Васючкова О.И., Крюковская И.В. и др. Учебник английского языка для студентов-юристов. Учебное пособие для студентов юридического факультета: В 2 ч. Ч.1. – Минск: Белгосуниверситет, 1999. – 169 с. Настоящее пособие представляет собой тематически организованный учебно-методический комплекс по проблемам, представляющим интерес для студентов-правоведов: профессия юриста, история государства и права, конституционное право. Каждый тематический раздел состоит из аутентичных (ам. и брит.) монологических и диалогических текстов с заданиями для разных видов чтения и аудирования, грамматического блока, разработки по домашнему чтению, текстов для дополнительного чтения. Цель пособия — обучить студентов чтению, реферированию, пониманию на слух текстов по специальности и ведению дискуссии. Предназначено для студентов первого курса юридического факультета. UNIT I Agents of the Law READING MATERIAL Text A. “Legal Profession” Task: read and translate the following text. England is almost unique in having two different kinds of lawyers, with separate jobs in the legal system. This division of the legal profession is of long standing and each branch has its own characteristic functions as well as a separate governing body. The training and career structures for the two types of lawyers are quite separate. The traditional picture of the English lawyer is that the solicitor is the general practitioner, confined mainly to the office.