Thornhill As a Walkable Jewish Suburb Daniel A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KAJ NEWSLETTER a Monthly Publication of K’Hal Adath Jeshurun Volume 48 Number 1

September 5, ‘17 י"ד אלול תשע"ז KAJ NEWSLETTER A monthly publication of K’hal Adath Jeshurun Volume 48 Number 1 MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD .כתיבה וחתימה טובה The Board of Trustees wishes all our members and friends a ,רב זכריה בן רבקה Please continue to be mispallel for Rav Gelley .רפואה שלמה for a WELCOME BACK The KAJ Newsletter welcomes back all its readers from what we hope was a pleasant and restful summer. At the same time, we wish a Tzeisechem LeSholom to our members’ children who have left, or will soon be leaving, for a year of study, whether in Eretz Yisroel, America or elsewhere. As we begin our 48th year of publication, we would like to remind you, our readership, that it is through your interest and participation that the Newsletter can reach its full potential as a vehicle for the communication of our Kehilla’s newsworthy events. Submissions, ideas and comments are most welcome, and will be reviewed. They can be emailed to [email protected]. Alternatively, letters and articles can be submitted to the Kehilla office. מראה מקומות לדרשת מוהר''ר ישראל נתן הלוי מנטל שליט''א שבת שובה תשע''ח לפ''ק בענין תוספת שבת ויו"ט ויום הכפורים ר"ה דף ט' ע"א רמב"ם פ"א שביתת עשור הל' א' ,ד', ו' טור או"ח סי' רס"א בב"י סוד"ה וזמנו, וטור סי' תר"ח תוס' פסחים צ"ט: ד"ה עד שתחשך, תוס' ר' יהודה חסיד ברכות כ"ז. ד"ה דרב תוס' כתובות מ"ז. -

Attachment No. 4

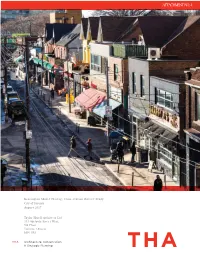

ATTACHMENT NO. 4 Kensington Market Heritage Conservation District Study City of Toronto August 2017 Taylor Hazell Architects Ltd. 333 Adelaide Street West, 5th Floor Toronto, Ontario M5V 1R5 Acknowledgements The study team gratefully acknowledges the efforts of the Stakeholder Advisory Committee for the Kensington Market HCD Study who provided thoughtful advice and direction throughout the course of the project. We would also like to thank Councillor Joe Cressy for his valuable input and support for the project during the stakeholder consultations and community meetings. COVER PHOTOGRAPH: VIEW WEST ALONG BALDWIN STREET (VIK PAHWA, 2016) KENSINGTON MARKET HCD STUDY | AUGUST 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE XIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION 13 2.0 HISTORY & EVOLUTION 13 2.1 NATURAL LANDSCAPE 14 2.2 INDIGENOUS PRESENCE (1600-1700) 14 2.3 TORONTO’S PARK LOTS (1790-1850) 18 2.4 RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT (1850-1900) 20 2.5 JEWISH MARKET (1900-1950) 25 2.6 URBAN RENEWAL ATTEMPTS (1950-1960) 26 2.7 CONTINUING IMMIGRATION (1950-PRESENT) 27 2.8 KENSINGTON COMMUNITY (1960-PRESENT) 33 3.0 ARCHAEOLOGICAL POTENTIAL 37 4.0 POLICY CONTEXT 37 4.1 PLANNING POLICY 53 4.2 HERITAGE POLICY 57 5.0 BUILT FORM & LANDSCAPE SURVEY 57 5.1 INTRODUCTION 57 5.2 METHODOLOGY 57 5.3 LIMITATIONS 61 6.0 COMMUNITY & STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 61 6.1 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 63 6.2 COMMUNITY CONSULTATION 67 7.0 CHARACTER ANALYSIS 67 7.1 BLOCK & STREET PATTERNS i KENSINGTON MARKET HCD STUDY |AUGUST 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS (CONTINUED) PAGE 71 7.2 PROPERTY FRONTAGES & PATTERNS -

Julia Dault National Post Thursday, February 03

Sacred sights: Robert Burley straddles the line between documentary and art with his collection of photographs of Toronto synagogues 'that were - and still are - so important to the Jewish community' Julia Dault National Post Thursday, February 03, 2005 INSTRUMENTS OF FAITH: TORONTO'S FIRST SYNAGOGUES Robert Burley The Eric Arthur Gallery to May 21 - - - In 2002, while Robert Burley's eldest son was studying the Torah and readying himself for his bar mitzvah, his father was embarking on his own mitzvah of sorts. Burley wanted to connect with his son's coming-of-age ceremony, so he started photographing downtown synagogues in an effort to learn even more about Judaism and the history of Toronto's Jewish community. (His interest in the faith and culture began in 1989, after he fell in love with his wife and converted to the religion.) Burley has since turned his scholarship into an exhibition made up of more than 20 images of the First Narayever, the Kiever, Knesseth Israel, Anshei Minsk, the Shaarei Tzedec and the Beaches Hebrew Institute; all are synagogues built by immigrant communities before 1940, and all still function today as sites of worship. "They were built with limited funds during fairly uncertain social and political times," says Burley. "They are small, intimate buildings that were -- and still are -- so important to the Jewish community." Using a panoramic camera borrowed from his friend and fellow photographer Geoffrey James as well as his own four by five, Burley fit himself into the small, holy spaces, capturing the sanctity of the bimah (reading platform), arks (or Aron Kodesh) and the Stars of David (Magen David) in both stark black and white and deep, brilliant colour. -

Synagogue Accessibility in the Greater Toronto Area Evelyn Lilith

Researching Disability: Synagogue Accessibility in the Greater Toronto Area Evelyn Lilith Finkler A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies and the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Magisteriate in Environmental Studies. York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada June, 2003 Library and Archives Biblioth6que et 1^1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'^dition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-80626-5 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-80626-5 NOTICE; AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commercials ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extra its substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced re produ its sans son autorisation. -

12 August 2011 / 12 Av, 5771 Volume 15 Number 30 ‘Boycotting Dialogue’ - a Strange South African Student Bedfellow PAGE 3

THE TABLE - A WARM, COMPLEX A SMALL- LIGHT ON JEWISH CULTURE / 12 TOWN STORY IN ISRAELI FILM DIRECTOR AVI EXOTIC NESHER COMES TO SA /12 INDIA / 13 Subscribe to our FREE epaper - go to www.sajewishreport.co.za www.sajewishreport.co.za Friday, 12 August 2011 / 12 Av, 5771 Volume 15 Number 30 ‘Boycotting dialogue’ - a strange South African student bedfellow PAGE 3 Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu articulating a new position on the pre-1967 lines, NETANYAHU ACCEPTS '67 LINES which was called a "very serious move" by one expert. Netanyahu is shown speaking at the weekly Cabinet meeting in Jerusalem on August 7. On his right is Speaker of the FOR TALKS, WITH CONDITIONS Knesset Reuven Rivlin. (PHOTO: HAIM ZACH / FLASH 90) PAGE 11 Norman Gordon - Cricketer Shirley Ancer - London riots - UK Travel SAICC’s upturn despite of yore scores ‘100’ / 2, 24 Building SA / 8 Jewish response / 10 / 14-15 global economy / 17 YOUTH / 20 SPORT / 24 LETTERS / 18 CROSSWORD & SUDOKU / 22 COMMUNITY BUZZ / 6 WHAT’S ON / 22 2 SA JEWISH REPORT 12 - 19 August 2011 SHABBAT TIMES PARSHA OF THE WEEK August 12/12 Av August 13/13 Av Spring of our national joy Va’etchanan Former SA Starts Ends cricketer 17:29 18:19 Johannesburg Norman 17:56 18:49 Cape Town Gordon, who 17:12 18:04 Durban PARSHAT VA’ETCHANAN Rabbi Ilan Raanan celebrated 17:32 18:24 Bloemfontein his 100th Dean of Yeshiva College Girls’ High School 17:28 18:21 Port Elizabeth birthday last 17:20 18:13 East London weekend. -

Biblioteca Centrală Universitară „Carol I” - Biblioteca De Ştiinţe Politice

Biblioteca Centrală Universitară „Carol I” - Biblioteca de Ştiinţe Politice RELAŢII BILATERALE ROMÂNO-CANADIENE : BIBLIOGRAFIE. II. Emigraţia românească în Canada Silvia-Adriana Tomescu Biblioteca Centrală Universitară „Carol I”Bucureşti Biblioteca de Ştiinţe Politice [email protected] DOCUMENTE DE ARHIVĂ ACNSAS. Fond documentar Bucureşti. Dosar SRI 214 /1969 : Activitatea fugarilor din ţările capitaliste împotriva RPR : 1949. f. 238-279. ACNSAS. Fond documentar Bucureşti. Dosar SRI 1780 : Scrisori ale liderilor PNŢ, interviuri şi comunicate către presă, note informative şi relatări ale evenimentelor de la 8 noiembrie 1945, articole preluate din „Dreptatea”. Textul acordului dintre BNR şi Chase National Bank din New York încheiat pentru obţinerea unui împrumut în vederea achiziţionării de alimente din SUA şi Canada (18 martie 1947). Documente din perioada : [1945-1947] ACNSAS. Fond documentar Bucureşti. Dosar SRI 4101 : Referitor la cereri adresate de cetăţeni de origine stabiliţi în SUA, Canada, Israel, Austria, lui Gheorghiu-Dej în septembrie 1960 pentru soluţionarea unor probleme de reintegrare a familiei sau graţieri. Documente din perioada : [1960] ACNSAS. Fond documentar Bucureşti. Dosar SRI 9539 : Publicaţii prohibite a intra în ţară. Referate şi note cu publicaţii străine interzise (în lb. română) din Canada şi S.U.A., articole din ziare. Documente din perioada : [1947] ACNSAS. Fond documentar Bucureşti. Dosar SRI 10014. Vol. 62 : Relaţiile M.A.I. român cu organele similare din Japonia, Kuweit, Etiopia, Liban, Zair, SUA, Canada, Mexic, Columbia, Brazilia, Israel, Burundi; vizite oficiale, note, impresii, penitenciare, şcolarizare studenţi. Documente din perioada : [aprilie-mai 1977]. ACNSAS. Fond documentar Bucureşti. Dosar SRI 10334 : Note întocmite de C. Olariu în anul 1951 referitoare la activitatea unor fugari români care au părăsit ţara înainte şi după 23 august 1944. -

An Examination of Toronto Synagogue Architecture, 1897-1937

Sharon Graham An Examination of Toronto Synagogue Architecture, 1897-1937 ynagogue architecture often acts as a unique element w ithin Sa city's architectural landsca pe. Toronto's pre-1937 syna gogues appea r to have copied each other styli sti ca ll y, creating a unique symbol of Judaism in the city (1937 marks the opening of the third Holy Bl ossom Temple and the beginning of the Jewish community's move away from the downtown core). On the whole, synagogue architecture in Toronto was very conserva ti ve, echoing trends that had lost their favour in other North Ameri ca n cities. Toronto congregations appeared to have found one style of building and they never strayed fro m it. Fig . 1. Ex terior. Holy Blossom Synagogue, Bond Street. John Wilson Siddall, architect. 1897. Three styli sti c groups of Toronto's pre-1 937 synagogues ca n {photo Sha ron Graham . 2000) be identified . The first group fea tures sma ll , hall-like buildings with plain ex teri ors and, due to their unremarkable architecture, they will not be d iscussed in this pape r. Other major synagogues, ori ginally built as churches and later bought by the Jewish com munity, are the second kind of buildings in Toronto, and they w ill not be discussed in this paper either. ' Holy Bl ossom on Bond Street (1897), Goel Tzedec (1907) and Beth Jacob (1922), Anshe Ki ev (1927) and Anshei Minsk (1 930) were substantial congrega ti ons w hose buildings were constructed o ri ginall y as syna gogues, and comprise the co ll ecti on of buildings that l will be examining. -

98-0335432 990O 200706.Pdf

OMB No 1545—0047 Form 9 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the lntemal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) Department 01 the Treasury Open to Public Internal Revenue Servtce > The organization may have to use a copy of this return to 5.atisfy state reporting reqmrements. Inspection A For the 2007 calendar year. or tax year beginning TEA” ) , 200] , and ending :3 be, 830 , 20 O ’l 8 Check It applicable Please c Name of orgamzat n ‘ 0 Employer identification number [3 Address change ram? U Ytt-Yeng—(ji‘hfl‘t 5* RON-*6 3 D- I] Name Change 11:33:! Number and street (or P.O box it mail is not delivered to street address) Room/swte E Telephone number g 3 are 3.53.3. .1:::,;,:3$D':ZF l "S I'UC- ' ' W, D A::n:::;wm "m ’EfOV‘TD - «Q HQK Z>V 9- C] Other (speCIfy) > applicable to section 527 organizations. [:l Application pending 0 Section 501(c)(3) organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt chantable H and'am "or trusts must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates”) DYes [2’ G WebSIte: b H(b) ll "Yes," enter number of affiliates > ............ H(c) Are all affiliates included? D Yes I: No J Organization type (check only one) > IE€01(c)( )4 Onsert no) 1:) 4947(a)(1) or [:I 527 (If “No,” attach a list. See instructions.) K Check here > [j if the organization IS not a 509(a)(3) supporting organization and its gross H(d) Is this a separate return tiled by an receipts are normally not more than $25,000. -

The Holocaust & Notions of a Jewish Homeland

Postmemory in Canadian Jewish Memoirs: The Holocaust & Notions of a Jewish Homeland Lizy Mostowski We Polish Jews … We, everlasting, who have perished in the ghettos and camps, and we ghosts who, from across seas and oceans, will some day return to the homeland and haunt the ruins in our unscarred bodies and our wretched, presumably spared souls. Julian Tuwim1 In his lecture at Concordia University in March of 2014, Professor Richard Menkis suggested that children of Holocaust survivors’ trauma be compared not to other children of survivors, but rather to those who have not directly inherited the trauma of the Holocaust at all, urging for a less hyperbolic reading of the impact inflicted by the Holocaust on post-Holocaust generations. The transmission of this trauma is generally studied when it is transmitted from Holocaust survivors to their children, with emphasis on particular and peculiar extreme behaviors and tendencies in both generational groups. However, as the second- and third-post-Holocaust generations in Canada have come of age, it has become apparent that Canadian * Lizy Mostowski is currently pursuing her PhD in Comparative and World Literature at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She holds BA and MA degrees in English Literature from Concordia University in Montreal, Canada. This article is a condensed version of her MA thesis, written under the supervision of her thesis advisor, Professor Bina Freiwald. 1 Julian Tuwim, My Żydzy polscy, We, Polish Jews, Magnes Press, Jerusalem 1984. pp. 155-187 ׀ Vol. 8, 2017 ׀ Israelis Jews, as historian Gerald Tulchinsky notes, now “recognize that the Holocaust is part of their collective identity” (Tulchinsky 2008: 459). -

(6 College £Treet

Historical Walking Tour of Kensin~ton Market (6 College £treet Barbara Myrvold T~Toronto Public Library ~. Historical Walking Tour of Kensington Market and College Street Barbara Myrvold Toronto Public Library Board Published with the assistance of Reflections '92 Ontario Ministry of Culture and Communications 1 Prefa< This v. memo' tonM: erston ested' Rosem Info amgn inforrr chives City of Archiv Kidd, I ISBN 0-920601-20-0 chives Copyright © 1993 Toronto Public Library Board Jutras 281 Front St. E. Toronto, Ontario M5A 4L2 Anne, Hospit Designed by Linda Goldman Metro] Printed and bound in Canada by City of Toronto Printing Unit missio ski, B~ Cover lliustration Unite( Kensington Market, Kensington Avenue, 1924. Cultur MTLT 11552 James A half-tone block taken from this photograph appeared in the cal Bo: Toronto Globe, 18 July 1924 (p. 9), with the caption: "Old World who pl scenes of Kensington Avenue, in the heart of Toronto's Jewish Alfred section, where every Thursday a market is held, with every variety of fruit and vegetables dear to the hearts of its patrons and by on sale from shop and wagon." S1 thewa Title Page Illustration Spa dina Avenue Senior Applique wall hanging by Linda Goldman, 1987 CantOl Courtesy of Baycrest Hospital for Geriatric Care Lillian the WE Key to Abbreviations in Picture Credits locatin AO Archives of Ontario tion a! CTA City of Toronto Archives Henry MTRL Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library architE TPL-SLHC Toronto Public Library Sanderson Branch, Westel Local History Collection TPLA Toronto Public Library Archives graph~ I ~ expert acknO\ Comm tions '~ Barba! Toront 2 Preface This walking tour is part of the Toronto 200 celebrations, which com memorate the founding of York, now Toronto. -

Lilith Finkler-Final Formatted

Tzedekah Tzedek and Tikkun Olam: Jusitice for Disabled Jews in the Synagogue By: Lilith Finkler Supervisor: Barbara Rahder Volume 9, Number 9 FES Outstanding Graduate Student Paper Series January 2004 ISSN 1702-3548 (online) ISSN 1702-3521 (print) Faculty of Environmental Studies York University Toronto, Ontario M3J 1P3 © 2004 Lilith Finkler All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written consent from the publisher. FES Outstanding Graduate Student Paper Series ABSTRACT Tzedekah (charity) tzedek (justice) and tikkun olam (social justice) are all elements of Jewish religious thought and practice. Members of the Jewish community sometimes view disability as related to charity. For example, when the need for a ramp is identified, congregants suggest a fundraiser. However, in order for disabled Jews to obtain justice, architectural adjustments must be accompanied by attitudinal changes. The rights of disabled persons must be conceived as human rights rather than as aspects of charity. TZEDEKAH, TZEDEK AND TIKKUN OLAM: JUSTICE FOR DISABLED JEWS IN THE SYNAGOGUE In this paper, I compare and contrast the notions of tzedek , tzedekah and tikkun olam . I argue that while these words may be used interchangeably in certain contexts, they are very different in theory and in practice. By discussing physical and attitudinal accessibility of synagogues and the (in)visibility of disability issues in the Jewish community, I hope to persuade readers that change is necessary. Tzedekah, Tzedek and Tikkun Olam all make reference to aspects of justice within Judaism. The meaning of each word varies, depending on context. Justice for some groups manifests differently than it does for others. -

The Globe and Mail Subject Photography

Finding Aid for Series F 4695-1 The Globe and Mail subject photography The following list was generated by the Globe & Mail as an inventory to the subject photography library and may not be an accurate reflection of the holdings transferred to the Archives of Ontario. This finding aid will be replaced by an online listing once processing is complete. How to view these records: Consult the listing and order files by reference code F 4695-1. A&A MUSIC AND ENTERTAINMENT INC. music stores A.C. CROSBIE SHIP AARBURG (Switzerland) AARDVARK animal ABACO ABACUS adding machine ABBA rock group ABBEY TAVERN SINGERS ABC group ABC TELEVISION NETWORK ABEGWAIT ferry ABELL WACO ABERDEEN city (Scotland) ABERFOYLE MARKET ABIDJAN city (Ivory Coast) ABITIBI PAPER COMPANY ABITIBI-PRICE INC. ABKHAZIA republic ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN Himalayan myth ABORIGINAL JUSTICE INQUIRY ABORIGINAL RIGHTS ABORIGINES ABORTION see also: large picture file ABRAHAM & STRAUS department store (Manhattan) ABU DHABI ABU SIMBEL (United Arab Republic) ACADEMIE BASEBALL CANADA ACADEMY AWARDS ACADEMY OF CANADIAN CINEMA & TELEVISION ACADEMY OF COUNTRY MUSIC AWARDS ACADEMY OF MEDICINE (Toronto) see: TORONTO ACADEMY OF MEDICINE 1 ACADIA steamship ACADIA AXEMEN FOOTBALL TEAM ACADIA FISHERIES LTD. (Nova Scotia) ACADIA steamship ACADIA UNIVERSITY (Nova Scotia) ACADIAN LINES LTD. ACADIAN SEAPLANTS LIMITED ACADIAN TRAIL ACAPULCO city (Mexico) ACCESS NETWORK ACCIDENTS - Air (Up to 1963) - Air (1964-1978) - Air (1979-1988) - Air (1988) - Lockerbie Air Disaster - Air (1989-1998) see also: large picture file - Gas fumes - Level crossings - Marine - Mine - Miscellaneous (up to 1959) (1959-1965) (1966-1988) (1989-1998) see also: large picture file - Railway (up to 1962) (1963-1984) (1985-1998) see also: large picture file - Street car - Traffic (1952-1979) (1980-1989) (1990-1998) see also: large picture file ACCORDIAN ACCUTANE drug AC/DC group ACHILLE LAURO ship ACID RAIN ACME LATHING AND DRYWALL LIMITED ACME SCREW AND GEAR LTD.