An Examination of Toronto Synagogue Architecture, 1897-1937

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uva Letzion Goel a Tefillah for Holding It Together Daily

Uva Letzion Goel A Tefillah for Holding it Together Daily Rabbi Zvi Engel ובא לציון גואל קדושה דסדרא - A Tefilla For Holding It Together Daily Lesson 1 (Skill Level: Entry Level) Swimming Against the Undercurrent of “Each Day and Its Curse” Sota 48a Note: What The Gemara (below) calls “Kedusha d’Sidra,” is the core of “Uva Letzion” A Parting of Petition, Praise & Prom Sota 49a Congrega(on Or Torah in Skokie, IL - R. Zvi Engel Uva Letzion Goel: Holding the World Together Page1 Rashi 49a: Kedusha d’sidra [“the doxology”] - the order of kedusha was enacted so that all of Israel would be engaged in Torah study each day at least to am minimal amount, such that he reads the verses and their translation [into Aramic] and this is as if they are engaged in Torah. And since this is the tradition for students and laymen alike, and [the prayer] includes both sanctification of The Name and learning of Torah, it is precious. Also, the May His Great Name Be Blessed [i.e. Kaddish] recited following the drasha [sermon] of the teacher who delivers drashot in public each Shabbat [afternoon], they would have this tradition; and there all of the nation would gather to listen, since it is not a day of work, and there is both Torah and Sanctification of The Name. Ever wonder why we recite Ashrei a second time during Shacharit? (Hint: Ashrei is the core of the praise of Hashem required to be able to stand before Him in Tefilla) What if it is part of a “Phase II” of Shacharit in which there is a restatement—and expansion—of some of its initial, basic themes ? -

Cultural Facilities 030109

A Map of Toronto’s Cultural Facilities A Cultural Facilities Analysis 03.01.10 Prepared for: Rita Davies Managing Director of Culture Division of Economic Development, Culture and Tourism Prepared by: ERA Architects Inc. Urban Intelligence Inc. Cuesta Systems Inc. Executive Summary In 1998, seven municipalities, each with its own distinct cultural history and infrastructure, came together to form the new City of Toronto. The process of taking stock of the new city’s cultural facilities was noted as a priority soon after amalgamation and entrusted to the newly formed Culture Division. City Council on January 27, 2000, adopted the recommendations of the Policy and Finance Committee whereby the Commissioner of Economic Development, Culture and Tourism was requested to proceed with a Cultural Facilities Masterplan including needs assessment and business cases for new arts facilities, including the Oakwood - Vaughan Arts Centre, in future years. This report: > considers the City of Toronto’s role in supporting cultural facilities > documents all existing cultural facilities > provides an approach for assessing Toronto’s cultural health. Support for Toronto’s Cultural Facilities Through the Culture Division, the City of Toronto provides both direct and indirect support to cultural activities. Direct support consists of : > grants to individual artists and arts organizations > ongoing operating and capital support for City-owned and operated facilities. Indirect support consists of: > property tax exemptions > below-market rents on City-owned facilities > deployment of Section 37 development agreements. A Cultural Facilities Inventory A Cultural Facility Analysis presents and interprets data about Toronto’s cultural facilities that was collected by means of a GIS (Global Information System) database. -

The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults Who Is Who? Who Is Behind It?

Human Rights Without Frontiers Int’l Avenue d’Auderghem 61/16, 1040 Brussels Phone/Fax: 32 2 3456145 Email: [email protected] – Website: http://www.hrwf.eu No Entreprise: 0473.809.960 The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults Who is Who? Who is Behind it? By Willy Fautré The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults About the so-called experts of the Israeli Center for Victims of Cults and Yad L'Achim Rami Feller ICVC Directors Some Other So-called Experts Some Dangerous Liaisons of the Israeli Center for Victims of Cults Conclusions Annexes Brussels, 1 September 2018 The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults Who is Who? Who is Behind it? The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults (ICVC) is well-known in Israel for its activities against a number of religious and spiritual movements that are depicted as harmful and dangerous. Over the years, the ICVC has managed to garner easy access to the media and Israeli government due to its moral panic narratives and campaign for an anti-cult law. It is therefore not surprising that the ICVC has also emerged in Europe, in particular, on the website of FECRIS (European Federation of Centers of Research and Information on Cults and Sects), as its Israel correspondent.1 For many years, FECRIS has been heavily criticized by international human rights organizations for fomenting social hostility and hate speech towards non-mainstream religions and worldviews, usually of foreign origin, and for stigmatizing members of these groups.2 Religious studies scholars and the scientific establishment in general have also denounced FECRIS for the lack of expertise of their so-called “cult experts”. -

KAJ NEWSLETTER a Monthly Publication of K’Hal Adath Jeshurun Volume 48 Number 1

September 5, ‘17 י"ד אלול תשע"ז KAJ NEWSLETTER A monthly publication of K’hal Adath Jeshurun Volume 48 Number 1 MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD .כתיבה וחתימה טובה The Board of Trustees wishes all our members and friends a ,רב זכריה בן רבקה Please continue to be mispallel for Rav Gelley .רפואה שלמה for a WELCOME BACK The KAJ Newsletter welcomes back all its readers from what we hope was a pleasant and restful summer. At the same time, we wish a Tzeisechem LeSholom to our members’ children who have left, or will soon be leaving, for a year of study, whether in Eretz Yisroel, America or elsewhere. As we begin our 48th year of publication, we would like to remind you, our readership, that it is through your interest and participation that the Newsletter can reach its full potential as a vehicle for the communication of our Kehilla’s newsworthy events. Submissions, ideas and comments are most welcome, and will be reviewed. They can be emailed to [email protected]. Alternatively, letters and articles can be submitted to the Kehilla office. מראה מקומות לדרשת מוהר''ר ישראל נתן הלוי מנטל שליט''א שבת שובה תשע''ח לפ''ק בענין תוספת שבת ויו"ט ויום הכפורים ר"ה דף ט' ע"א רמב"ם פ"א שביתת עשור הל' א' ,ד', ו' טור או"ח סי' רס"א בב"י סוד"ה וזמנו, וטור סי' תר"ח תוס' פסחים צ"ט: ד"ה עד שתחשך, תוס' ר' יהודה חסיד ברכות כ"ז. ד"ה דרב תוס' כתובות מ"ז. -

This Document Was Retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act E-Register, Which Is Accessible Through the Website of the Ontario Heritage Trust At

This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act e-Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre électronique. tenu aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. ------~---- -- ·- Jeffrey A. Abrams Acting City Clerk • City Clerk's Division Tel: (416) 397-0778 City of Toronto Archives Fax: (416) 392-9685 255 Road Toronto, Ontario M5R 2V3 [email protected] • http://www.city.toronto.on.ca ,. • IN THE l\iATTER OF THE ONTAP.!O HERlTAGE ACT • • ' 1 • R.S.O. 1990 CHAPTER. --~ . & AND 395-397 CITY OF TORONTO, PROVINCE OF ONTARIO NOTICE OF PASSING OF BY-LAW Ontario Heritage Foundation 10 Adelaide Street East I Toronto, Ontario I • MSC 1J3 , Take notice that the Council of the City of Toronto has passed By-law No. 677-2001 to designate 395-397 Markham Street as being of architectural and historical value or interest. • I • Dated at Toronto this 13th day of August, 2001. ' , ' i ' I • ' Jeffrey A. Abrams I Acting City Clerk - • • ' - ---' . ' ' • Authority: Toronto East York Community Council Report No. 6, Clause No. 48, as adopted by City of Toronto Council on July 24, 25 and 26, 2001 Enacted by Council: July 26, 2001 CITY OF TORONTO BY-LAW No. 677-2001 To designate the property at 395-397 Markham Street (T. R. Earl Houses) as being of architectural and historical value or interest. REAS authority was granted by Council to designate the property at 395-397 Markham Street (T. -

Matot-Maasei Copy.Pages

BS”D South Head Youth Parasha Sheet Parashat Matot Parashat Matot teaches us the importance of our words. One might think that the words we speak are not important. However, this is not so. The Torah teaches us that words are very important. A Jew should be careful with the words he uses, particularly when making a promise. This is because when we make a promise we are responsible to keep it. For this reason, it is actually best to avoid making promises, because when a person breaks his promise he has committed a sin. Therefore, rather than making a promise, it’s a good idea to say the words ‘Bli Neder'. These words translate to mean ‘it’s not a promise’. So when a person says that he is going to do something, and adds in the words ‘Bli Neder’ he is not bound by any promises. Therefore, if he forgets to do what he said he was going to do, the person has not committed a sin. Of course, there is the off-chance that we might forget to say the words ‘Bli Neder’ and we might actually promise to do something which for some reason we do not end up doing. Therefore the Torah teaches us a few ways of undoing a promise. A person may go to a Beit Din, a Jewish Court or to a great Torah scholar and explain to the Beit Din or the Torah scholar the promise he made. The Beit Din or Torah scholar can then nullify the promise for the person if they find a good reason to cancel it. -

Attachment No. 4

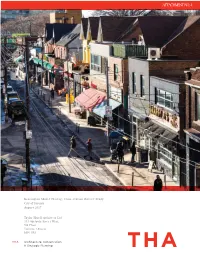

ATTACHMENT NO. 4 Kensington Market Heritage Conservation District Study City of Toronto August 2017 Taylor Hazell Architects Ltd. 333 Adelaide Street West, 5th Floor Toronto, Ontario M5V 1R5 Acknowledgements The study team gratefully acknowledges the efforts of the Stakeholder Advisory Committee for the Kensington Market HCD Study who provided thoughtful advice and direction throughout the course of the project. We would also like to thank Councillor Joe Cressy for his valuable input and support for the project during the stakeholder consultations and community meetings. COVER PHOTOGRAPH: VIEW WEST ALONG BALDWIN STREET (VIK PAHWA, 2016) KENSINGTON MARKET HCD STUDY | AUGUST 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE XIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION 13 2.0 HISTORY & EVOLUTION 13 2.1 NATURAL LANDSCAPE 14 2.2 INDIGENOUS PRESENCE (1600-1700) 14 2.3 TORONTO’S PARK LOTS (1790-1850) 18 2.4 RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT (1850-1900) 20 2.5 JEWISH MARKET (1900-1950) 25 2.6 URBAN RENEWAL ATTEMPTS (1950-1960) 26 2.7 CONTINUING IMMIGRATION (1950-PRESENT) 27 2.8 KENSINGTON COMMUNITY (1960-PRESENT) 33 3.0 ARCHAEOLOGICAL POTENTIAL 37 4.0 POLICY CONTEXT 37 4.1 PLANNING POLICY 53 4.2 HERITAGE POLICY 57 5.0 BUILT FORM & LANDSCAPE SURVEY 57 5.1 INTRODUCTION 57 5.2 METHODOLOGY 57 5.3 LIMITATIONS 61 6.0 COMMUNITY & STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 61 6.1 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 63 6.2 COMMUNITY CONSULTATION 67 7.0 CHARACTER ANALYSIS 67 7.1 BLOCK & STREET PATTERNS i KENSINGTON MARKET HCD STUDY |AUGUST 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS (CONTINUED) PAGE 71 7.2 PROPERTY FRONTAGES & PATTERNS -

Residents Day Virtual Meeting Henry Ford Health System

May 7, 2021 Residents Day Virtual Meeting Hosted by: Henry Ford Health System - Detroit Internal Medicine Residency Program Medical Student Day Virtual Meeting Sponsored by: & Residents Day & Medical Student Day Virtual Program May 7, 2021 MORNING SESSIONS 6:45 – 7:30 AM Resident Program Directors Meeting – Sandor Shoichet, MD, FACP Via Zoom 7:30 – 9:30 AM Oral Abstract Presentations Session One Abstracts 1-10 9:00 – 10:30 AM Oral Abstract Presentations Session Two Abstracts 11-20 10:30 AM – 12:00 PM Oral Abstract Presentations Session Three Abstracts 21-30 KEYNOTE SESSON COVID Perspectives: 1. “ID Perspective: Inpatient Work and Lessons from Infection Control Point of View” – Payal Patel, MD, MPH 12:00 – 1:00 PM 2. “PCCM Perspective: Adding Specific Lessons from ICU Care/Burden and Possible Response to Future Pandemics” – Jack Buckley, MD 3. “Pop Health/Insurance Perspective – Population Health/Social Net of Health/Urban Under-Represented Care During COVID” – Peter Watson, MD, MMM, FACP AFTERNOON SESSIONS RESIDENTS PROGRAM MEDICAL STUDENT PROGRAM Residents Doctor’s Dilemma™ 1:15 – 2:00 PM Nicole Marijanovich MD, FACP 1:00 – 1:30 pm COVID Overview – Andrew Jameson, MD, FACP Session 1 Residents Doctor’s Dilemma™ 2:00 – 2:45 PM 1:30 – 2:15 am COVID – A Medical Students Perspective Session 2 Residents Doctor’s Dilemma™ 4th Year Medical Student Panel: Post-Match Review 2:45 – 3:30 PM 2:15 – 3:00 pm Session 3 of Interviews Impacted by COVID Residents Doctor’s Dilemma™ Residency Program Director Panel: A Residency 3:30 – 4:15 PM 3:00 – 3:45 -

The Relationship Between Religiosity and Mental Illness Stigma in the Abrahamic Religions Emma C

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2018 The Relationship Between Religiosity and Mental Illness Stigma in the Abrahamic Religions Emma C. Bushong [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Bushong, Emma C., "The Relationship Between Religiosity and Mental Illness Stigma in the Abrahamic Religions" (2018). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. 1193. https://mds.marshall.edu/etd/1193 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN RELIGIOSITY AND MENTAL ILLNESS STIGMA IN THE ABRAHAMIC RELIGIONS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate In Psychology by Emma C. Bushong Approved by Dr. Keith Beard, Committee Chairperson Dr. Dawn Goel Dr. Keelon Hinton Marshall University August 2018 © 2018 Emma C. Bushong ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the educators, friends, and family who supported me through this process. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... vii! -

A Jewish Woman's Escape from Iran Community Author and Inspirational Speaker Iranian-Born Dr

Jewish Community AKR NJewishBOARD OF AKRON News September 2019 | 5780 | Vol. 89, No. 7 www.jewishakron.org Fleeing the Hijab: Campaign A Jewish woman's escape from Iran Community Author and inspirational speaker Iranian-born Dr. Her journey began at age thirteen when she Impact Sima Goel will share her story of escape, courage, and spontaneously defended a Baha’i classmate against a freedom on Tuesday, Oct. 29 at 5:30 p.m. in a free, schoolyard bully. This act triggered events that would community-wide presentation on the Schultz Campus eventually take her into danger and far from her Jewish Akron united for Jewish Life. beloved homeland. and ready to respond As an Iranian teenager, she crossed the Following the 1979 Iranian Revolution, in time of crisis most dangerous desert in the world rather every female had to wear a loose dress, Page 6 than accept the restrictions of life in Iran headscarf, and pants that hid the shape of the early 1980s. of one’s legs. Women feared going about without proper attire. Shortly after turning 17, Dr. Goel and another teenage girl traveled, hid and As living conditions worsened and Dr. Spotlight on made their way past smugglers, rapists Goel eventually lost access to education, and murderers out of Iran into Pakistan she desperately sought a better life. After Sarah Foster and then on to the West. being blacklisted at her school and forced into hiding, she ultimately left her home Dr. Goel lived under two dictatorships; Dr. Sima Goel in Shiraz. Her mother knew smugglers Get to know the The Shah and The Ayatollah Khomeini, who could help the young girl flee, but the possibility new Akron Hillel she knows what is at stake. -

Democratic Culture and Muslim Political Participation in Post-Suharto Indonesia

RELIGIOUS DEMOCRATS: DEMOCRATIC CULTURE AND MUSLIM POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN POST-SUHARTO INDONESIA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science at The Ohio State University by Saiful Mujani, MA ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor R. William Liddle, Adviser Professor Bradley M. Richardson Professor Goldie Shabad ___________________________ Adviser Department of Political Science ABSTRACT Most theories about the negative relationship between Islam and democracy rely on an interpretation of the Islamic political tradition. More positive accounts are also anchored in the same tradition, interpreted in a different way. While some scholarship relies on more empirical observation and analysis, there is no single work which systematically demonstrates the relationship between Islam and democracy. This study is an attempt to fill this gap by defining Islam empirically in terms of several components and democracy in terms of the components of democratic culture— social capital, political tolerance, political engagement, political trust, and support for the democratic system—and political participation. The theories which assert that Islam is inimical to democracy are tested by examining the extent to which the Islamic and democratic components are negatively associated. Indonesia was selected for this research as it is the most populous Muslim country in the world, with considerable variation among Muslims in belief and practice. Two national mass surveys were conducted in 2001 and 2002. This study found that Islam defined by two sets of rituals, the networks of Islamic civic engagement, Islamic social identity, and Islamist political orientations (Islamism) does not have a negative association with the components of democracy. -

Julia Dault National Post Thursday, February 03

Sacred sights: Robert Burley straddles the line between documentary and art with his collection of photographs of Toronto synagogues 'that were - and still are - so important to the Jewish community' Julia Dault National Post Thursday, February 03, 2005 INSTRUMENTS OF FAITH: TORONTO'S FIRST SYNAGOGUES Robert Burley The Eric Arthur Gallery to May 21 - - - In 2002, while Robert Burley's eldest son was studying the Torah and readying himself for his bar mitzvah, his father was embarking on his own mitzvah of sorts. Burley wanted to connect with his son's coming-of-age ceremony, so he started photographing downtown synagogues in an effort to learn even more about Judaism and the history of Toronto's Jewish community. (His interest in the faith and culture began in 1989, after he fell in love with his wife and converted to the religion.) Burley has since turned his scholarship into an exhibition made up of more than 20 images of the First Narayever, the Kiever, Knesseth Israel, Anshei Minsk, the Shaarei Tzedec and the Beaches Hebrew Institute; all are synagogues built by immigrant communities before 1940, and all still function today as sites of worship. "They were built with limited funds during fairly uncertain social and political times," says Burley. "They are small, intimate buildings that were -- and still are -- so important to the Jewish community." Using a panoramic camera borrowed from his friend and fellow photographer Geoffrey James as well as his own four by five, Burley fit himself into the small, holy spaces, capturing the sanctity of the bimah (reading platform), arks (or Aron Kodesh) and the Stars of David (Magen David) in both stark black and white and deep, brilliant colour.