Sciencedirect.Com Sciencedirect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

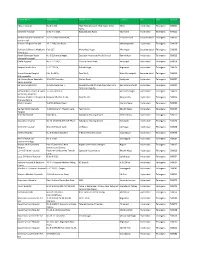

State City Hospital Name Address Pin Code Phone K.M

STATE CITY HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS PIN CODE PHONE K.M. Memorial Hospital And Research Center, Bye Pass Jharkhand Bokaro NEPHROPLUS DIALYSIS CENTER - BOKARO 827013 9234342627 Road, Bokaro, National Highway23, Chas D.No.29-14-45, Sri Guru Residency, Prakasam Road, Andhra Pradesh Achanta AMARAVATI EYE HOSPITAL 520002 0866-2437111 Suryaraopet, Pushpa Hotel Centre, Vijayawada Telangana Adilabad SRI SAI MATERNITY & GENERAL HOSPITAL Near Railway Gate, Gunj Road, Bhoktapur 504002 08732-230777 Uttar Pradesh Agra AMIT JAGGI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL Sector-1, Vibhav Nagar 282001 0562-2330600 Uttar Pradesh Agra UPADHYAY HOSPITAL Shaheed Nagar Crossing 282001 0562-2230344 Uttar Pradesh Agra RAVI HOSPITAL No.1/55, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2521511 Uttar Pradesh Agra PUSHPANJALI HOSPTIAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Pushpanjali Palace, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2527566 Uttar Pradesh Agra VOHRA NURSING HOME #4, Laxman Nagar, Kheria Road 282001 0562-2303221 Ashoka Plaza, 1St & 2Nd Floor, Jawahar Nagar, Nh – 2, Uttar Pradesh Agra CENTRE FOR SIGHT (AGRA) 282002 011-26513723 Bypass Road, Near Omax Srk Mall Uttar Pradesh Agra IIMT HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Ganesh Nagar Lawyers Colony, Bye Pass Road 282005 9927818000 Uttar Pradesh Agra JEEVAN JYOTHI HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTER Sector-1, Awas Vikas, Bodla 282007 0562-2275030 Uttar Pradesh Agra DR.KAMLESH TANDON HOSPITALS & TEST TUBE BABY CENTRE 4/48, Lajpat Kunj, Agra 282002 0562-2525369 Uttar Pradesh Agra JAVITRI DEVI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL 51/10-J /19, West Arjun Nagar 282001 0562-2400069 Pushpanjali Hospital, 2Nd Floor, Pushpanjali Palace, -

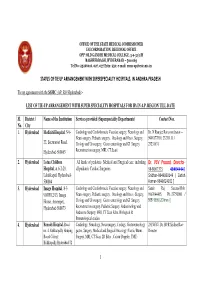

1 Status of Tie up Arrangement With

OFFICE OF THE STATE MEDICAL COMMISSIONER ESI CORPORATION, REGIONAL OFFICE OPP: OLD GANDHI MEDICAL COLLEGE, 5-9-31/1/B BASHEERBAGH, HYDERABAD – 500 063 Tel No: 23266016, 027, 037 Extn: 250; e-mail: [email protected] STATUS OF TIE UP ARRANGEMENT WITH SUPERSPECIALITY HOSPITALS, IN ANDHRA PRADESH Tie up agreement with the SSMC (AP, RO Hyderabad) :- LIST OF TIE-UP ARRANGEMENT WITH SUPER SPECIALITY HOSPITALS FOR IPs IN A.P. REGION TILL DATE Sl. District / Name of the Institution Services provided (Superspeciality Departments) Contact Nos. No. City 1. Hyderabad Mediciti Hospital , 5-9- Cardiology and Cardiothoracic Vascular surgery, Neurology and Dr. N Ramjee Rao,coordinator— Neuro surgery. Pediatric surgery. Oncology and Onco. Surgery, 9908177810, 23231111 / 22, Secretariat Road, Urology and Urosurgery, Gastro enterology and GI Surgery. 23231631 Hyderabad-500063 Reconstruction surgery, MRI, CT Scan) 2. Hyderabad Lotus Children All kinds of pediatric- Medical and Surgical care, including Dr. VSV Prasad, Director - Hospital , at 6-2-29, all pediatric Cardiac Surgeries 9849067373 , 40404444/ Lakdikapul, Hyderabad- Sridhar-9849000149 / Satish 500004 Kumar-9849024011 ] 3. Hyderabad Image Hospital , 8-3- Cardiology and Cardiothoracic Vascular surgery, Neurology and Samir Raj Saxena-Mob. 903/F/12/13, Image Neuro surgery. Pediatric surgery. Oncology and Onco.- Surgery, 9963944495, Ph.-23750000 / House, Ameerpet,, Urology and Urosurgery, Gastro enterology and GI Surgery. 55519999( 20 lines )] Hyderabad-500073 Reconstruction surgery, Pediatric Surgery, Endocrinology and Endocrine Surgery, MRI, CT Scan Echo, Biological & Immunological studies 4. Hyderabad Remedy Hospital, Road Cardiology, Neurology, Neurosurgery, Urology, Gastroenterology 23158787, Dr. BVR Sridhar Rao- no. 4, Kukkatpally Housing gastro. Surgery, Medical and Surgical Oncology, Plastic/ Burns Director Board Colony, Surgery, MRI, CT Scan, 2D Echo , Colour Doppler, TMT) Kukkatpally,Hyderabad-72 1 5. -

EMAILID Andhra Pradesh Hyderabad HO

STATE CITY Hospital ID HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS PINCODE PHONE MOBILE FAX CONTACTPERSON- (desig) EMAILID Andhra Pradesh Hyderabad HOS-HYD-3330 Apoorva Hospital 46 / A Santosh Nagar, Mehindipatnam 500028 040-65503232 NA 04023526757 NA NA Andhra Pradesh Hyderabad HOS-HYD-11 Bapuji Hospital 7-44 Bapujinagar, Nacharam 500076 040-27175567 NA 04027158358 NA NA Andhra Pradesh Hyderabad HOS-HYD-10 Bristlecone Hospital 3-4-136/A, Street No. 6, Near Barkatpura Chaman, Pf Office 500027 040-2756365 NA 040-45999901 NA NA Andhra Pradesh Hyderabad HOS-HYD-2112 Clear Vision Eye Center 3-6-272, Nvk Towers, Himayathnagar 500029 040-23225386 NA 04023221522 NA NA Andhra Pradesh Hyderabad HOS-HYD-6208 Devishetty Hospital A3, Moti Valley, Thirumalagirry, Beside Acer Motors, Secunderabad 500003 04066046245 NA 0 NA NA Andhra Pradesh Hyderabad HOS-HYD-4149 Eashwar Lakshmi Hospital Plot No.9, Gandhi Nagar 500080 040-27618442 NA 04066566665 NA NA Andhra Pradesh Hyderabad HOS-HYD-4206 Gbr Hospital Beside Fruit Market, Chaitanya Puri, Dilshuknagar 502103 040-66802345 NA 04024147890 NA NA Andhra Pradesh Hyderabad HOS-HYD-58 Geetha Multi Speciality Hospital Road No 4, West Maradpally, Secunderabad 500026 040-27801272 NA 040-27716287 NA NA Andhra Pradesh Hyderabad HOS-HYD-6209 Haritha Hospital #1-111/2/2/1, Police Line, Kondapur 500081 040 23002400 NA 04023067193 NA NA Andhra Pradesh Hyderabad HOS-HYD-547 Hope Childrens Hospital 5-9-24 / 81 Lake Hills Road, Basheerbagh 500463 040-23223782 NA 04023261098 NA NA Andhra Pradesh Hyderabad HOS-HYD-5069 Janani Hospital 3-12-58 -

Study of Neuroreceptors in Native ACL Stump and Autologus Hamstring

Journal of Arthroscopy and Joint Surgery 4 (2017) 79–82 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Arthroscopy and Joint Surgery journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jajs Research paper Study of neuroreceptors in native ACL stump and autologus hamstring tendon graft Sandeep T. George*, J.V.S. Vidya Sagar, S Radhaa, Tameem Afroz Aware Global Hospital, L.B. Nagar, Hyderabad, India A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Background: Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is a very common arthroscopic surgery. All Received 23 December 2015 around the world the commonest autograft preferred is hamstring tendon. Present trend is more in favor Received in revised form 21 July 2016 of retaining the native ACL stump as the available neuroreceptors in the stump might help in early Accepted 9 August 2017 recovery of proprioception after ACL reconstruction. Available online 14 August 2017 Methods: This is a prospective study done on 56 cases. We took biopsy samples from knee joints of patients who had undergone arthroscopic ACL reconstruction at our hospital from native ACL stump as Keywords: well as the graft (Semitendinosus) and sent them for immunohistological examination using S-100 ACL deficient knee Protein and NFP (Neural filament protein). Stump preserving ACL reconstruction fi ’ Neuroreceptors Results: Chronicity of ACL de cient knee s (injury to surgery more than 6 months) revealed poor positivity Chronic ACL deficient knee for neuroreceptors in sample A. After 3 months of injury there was a gradual decrease in positivity for Early ACL reconstruction neuroreceptors with persistence of these neural elements upto 6 months within remnant ACL stump. -

RHICL Network Hospital List.Xlsx

Hospital Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Location City State Pincode Aditya Hospital No.4-1-160, Tilak Road,Opposite Tilak Nagar Water Abids Hyderabad Telangana 500001 Tanks, Kamineni Hospital D.No.4-1-1227, Boggulakunta Road, King Kothi Hyderabad Telangana 500001 Krishna Institute Of Medical 1-8-31/1 Ministers Road, Secunderabad Secunderabad Telangana 500003 Sciences Ltd Premier Hospitals Pvt Ltd 12-2-718,Cross Road, Mahedipatnam Hyderabad Telangana 500028 Rainbow Children's Medicare Plot C17, Manovikas Nagar, Vikrampuri Secunderabad Telangana 500009 Private Ltd. Advalli Damodar Reddy No.9-2,Sharada Nagar, Opposite Hyderabad Public School, Ramanthpur Hyderabad Telangana 500013 Memorial Hospital Challa Hospital No.7-1-71/A/1, Dharam Karan Road, Ameerpet Hyderabad Telangana 500016 Swapna Health Care 6-3-1111/19, Nishath Bagh, Begumpet Hyderabad Telangana 500016 Basant Sahney Hospital Plot No 29/A, Road No.1, West Marredpally Secunderabad Telangana 500026 Multispeciality Sai Krishna Super Speciality 3-51,VLR Complex, Station Road, Kachiguda Hyderabad Telangana 500027 Neuro Hospital Sai Vani Hospital Ltd. 1-2-365/36/6 And 7, Ramakrishna Mutt Road,Opposite Indira Ramakrishna Mutt Hyderabad Telangana 500029 Park,Domalaguda, Sathya Kidney Centre & Super 3-6-426,Street-4, Himayath Nagar Hyderabad Telangana 500029 Speaciality Hospitals Rainbow Children's Hospital & Banjara Hills,Plot No 22, Road No 10, Banjara Hills Hyderabad Telangana 500034 Prenatal Centre Mythri Hospital 5-4/12-16,Main Road, Chanda Nagar Hyderabad Telangana 500050 Sai Ram -

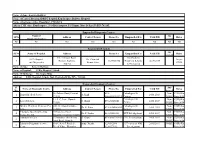

Sl.No Name of Diagnostic Centre Address Contect Person Phone No

Name of Zone:-Eastern Railway Name of Central/Division/SDH/PU hospital:Kanchrapara Railway Hospital Name of Incharge:A.Das Choudhuri, CMS/KPA Adress-CMS office Kanchrapara , P.O-Kanchrapara, P.S-Bizpur, Dist.-24 Pgs (N) PIN-743145, E. Mail:[email protected], Phone:9002027500 Empanelled Diagnostic Centres Name of Any Sl.No Address Contect Person Phone No. Empanelled For Valid Till Rates Diagnostic Centre accredi Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Empanelled Hospitals Any Sl.No Name of Hospital Address Phone No. Empanelled For Valid Till Rates accredi 111,/1 Jessore Road,. For Cashless ECO Hospital Dr. Chanchal As per 1 Barasat, Kolkata- 3325626854 Treatment Scheme 04.05.2019 and Diagnostice Kumar Saha CGHS 700124 in Emergency Name of Zone: Eastern Railway Name of Hospital: E.Rly.Hospital/ Liluah Name Of Incharge: Dr. Gopa Shina Address: E.Rly.Hospital, Liluah, Dist.-Howrah (W.B), PIN - 711204. email : [email protected] Phone no.:033-26545386, 9002029700. Empanelled Diagnostic Centres: Sl. Any Name of Diagnostic Centre Address Contact Person Phone No. Empanelled For Valid Till Rates No. Accred 26/Dobson Road, Howrah – 033- Pathological & Non- CGHS/Ko 1 Bansal Medical Service A.Singh 24.01.2019 711101 26660102/1847/1 Cardiac NABL lkata-2014 11/ I, C. Lane, Howrah – Pathological & Non- CGHS/Ko 2 Lasco Medicare S. Ghosh 033-26320640 24.01.2019 711201. Cardiac NABL lkata-2014 MCKV Health & Medicare Pvt. 243, G.T.Road, Liluah – PathologicalInvestigations & Non- CGHS/Ko 3 Dr. K. Paira 033-26548604/05 24.01.2019 LTd., 711204. Cardiac NABL lkata-2014 Uttarpara Speech & Hearing 4/Chatterjee Street, Non- CGHS/Ko 4 Dr. -

JOURNAL of ARTHROSCOPY and JOINT SURGERY an Official Publication of the International Society for Knowledge for Surgeons on Arthroscopy and Arthroplasty

JOURNAL OF ARTHROSCOPY AND JOINT SURGERY An official publication of the International Society for Knowledge for Surgeons on Arthroscopy and Arthroplasty AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.1 • Editorial Board p.1 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 2214-9635 DESCRIPTION . Journal of Arthroscopy and Joint Surgery (JAJS) is committed to bring forth scientific manuscripts in the form of original research articles, current concept reviews, meta-analyses, case reports and letters to the editor. The focus of the Journal is to present wide-ranging, multi-disciplinary perspectives on the problems of the joints that are amenable with Arthroscopy and Arthroplasty. Though Arthroscopy and Arthroplasty entail surgical procedures, the Journal shall not restrict itself to these purely surgical procedures and will also encompass pharmacological, rehabilitative and physical measures that can prevent or postpone the execution of a surgical procedure. The Journal will also publish scientific research related to tissues other than joints that would ultimately have an effect on the joint function. Benefits to authors We also provide many author benefits, such as free PDFs, special discounts on Elsevier publications and much more. Please click here for more information on our author services. Please see our Guide for Authors for information on article submission. If you require any further information or help, please visit our Support Center. ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING . Scopus Embase EDITORIAL BOARD . Editor-in-Chief Sanjeev Anand, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust Department of Orthopaedics, Leeds, United Kingdom Hemant Pandit, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust Department of Orthopaedics, Leeds, United Kingdom Amol Tambe, Derby Hospital Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Derby, United Kingdom Executive Editor Ravi Gupta, Government Medical College and Hospital Department of Orthopaedics, Chandigarh, India Lalit Maini, Maulana Azad Medical College, Dept. -

Ifko Tokio South Zone

SOUTH NOV IFFCO TOKIO NETWORK HOSPITALS FOR CASHLESS - SOUTH REGION Hospitals in bold & marked with** are Preffered ServiCe Provider, with whom ITGI has Negotiated paCkage rates ANDHRA PRADESH HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS CITY STD code Phone No. SRI SAI MATERNITY & GENERAL HOSPITAL** NEAR RAILWAY GATE , GUNJ ROAD ADILABAD 08732 200103 V.N. NURSING HOME & EMERGENCY HOSPITAL** D.NO. 3-2-117 E, COLLEGE ROAD AMALAPURAM 08856 231166-232166 AASHA HOSPITAL** 7-201, COURT ROAD, ANANTAPUR ANANTAPUR 08554 245755 DR. AKBAR EYE HOSPITAL 12-3-234 , 6TH CROSS SAI NAGAR ANANTAPUR 08554 235009 MYTHRI HOSPITAL** KAMALA NAGAR ANANTAPUR 08554 274630 PADMAVATHI HOSPITALS NEAR GENERAL HOSPITAL , ARAVINDA NAGAR , 2ND CROSS ANANTAPUR 08554 249966 SNEHALATHA HEALTHCARE COMPLEX, NEAR GANGA GAURI CINE COMPLEX, VAATSALYA HOSPITAL ANANTHPUR 08554 277077 KHAZANAGAR DR. AGARWAL'S EYE HOSPITAL LTD.** 22,339/2 , OPP TO S.B.I. COLONY CHITTOOR 08572 222255 ASRAM HOSPITAL** N.H.-5, MALAKA PURAM ELURU 08812 249361-62 SWARUPARANI NURSING HOME** 238-5/90 , RAMACHANDRA RAO PET,WEST GODAVARI ELURU 08812 230935 AMMA CHILDREN'S HOSPITAL D.NO. 13-7-109/D , OLD CLUB ROAD , GUNTURUVARI THOTA GUNTUR 0863 2266000 ARUNA HOSPITAL PRAKASAM ROAD , GANGANAMMAPET , TENALI , GUNTUR GUNTUR 08644 226314 ASWINI HOSPITALS** NEAR R.T.C. , BUS STAND , MANGALAGIRI ROAD GUNTUR 0863 2227000/2228000 B M R HOSPITAL** 6TH LANE , 2ND CROSS ROAD , ARUNDELPET GUNTUR 0863 2241370 8TH LANE , GUNTURIVARTHODA , OLD CLUB ROAD , OPP. RTC BUS STAND , COASTAL CARE HOSPITAL GUNTUR 0863 2233377 KOTHAPET LALITHA SUPERSPECIALITY HOSPITAL GOWRISANKAR THEATRE ROAD KOTHAPET, GUNTUR GUNTUR 0863 2222866/2217401/2217402 D.NO. 5 , 1 16&17 , OLD PALNADU BUS STAND PALNADU ROAD , MOTHER THERESA MULTI SPECIALITY HOSPITAL GUNTUR 08647 227070 NARASARAOPET PADMAVATHY SUPER SPECIALITY HOSPITAL OPP: TELEPHONE EXCHANGE & POST OFFICE, KOTHAPET, GUNTUR GUNTUR 0863 2222222 R K EYE CENTRE OPP. -

NRI's First City - Shamshabad, Hyderabad Freehold Residential Plot in Shamshabad,Hyderabad

https://www.propertywala.com/nris-first-city-hyderabad NRI's First City - Shamshabad, Hyderabad Freehold Residential Plot in Shamshabad,Hyderabad. Well Developed Residential plots (Greater Community) for Sale In Shamshabad. NRI's First surrounded world class Facility like RGI Airport, Metro, corporate Hubs, That are just Ac Gear-shift Away excellent. Project ID : J643119053 Builder: NRI's Properties: Residential Plots / Lands, Agricultural Plots / Lands Location: NRI's First city, Shamshabad, Hyderabad - 500003 (Telangana) Completion Date: Dec, 2016 Status: Started Description NRI's First City Well Developed Residential Plots (Greater Community) for Sale In Shamshabad . It surrounded world class Facility like RGI Airport, Metro, corporate Hubs, That are just A Gear-shift Away Excellent Educational Belt, Hospital,7-star and 5 star Hotels , shopping Malls, Multiplexes, world class Golf course, Metro Link soon to RGI. The Serenity waterfront, A club and resort, is aesthetically integrated within the landscape of NRI’s First City. Developments: Compound wall with common gate Layout planned as per Vaasthu Perfectly laid wide Black Top road Electrical Lines & Underground drainage lines Visitors Guest House area Overhead Tank with active water lines for each plot 24*7 security and Gardner for maintenance Flourished Greenery Park and play area for Children Amenities: Suitable demarcated plots to suit your budget Just 4 kms from Rajiv Gandhi International Airport Just 2 kms from Hyderabad to Bangalore NH-7 to site Well connected by MMTS and APSRTC -

SR No HOSPITAL NAME

HOSPITAL NAME (Hospitals marked with** S R are Preffered Provider STD Telephon Address City Pin Rohini Code State Zone No Network, with whom ITGI code e has Negotiated package rates) 1 Aasha Hospital** 7-201, Court Road Anantapur 515001 08554 245755 8900080169586 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 2 Aayushman The Family Hospital**45/142A1, V.R. ColonyKurnool 518003 08518 254004 8900080172005 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 3 Akira Eye Hospital** Aryapuram Rajahmundry 533104 0883 2471147 8900080180079 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 4 Andhra Hospitals** C.V.R. Complex, PrakasamVijayawada Road 520002 0866 2574757 8900080172531 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 5 Apex Hospital # 75-6-23, PrakashnagarRajahmundry Rajahmundry 533103 0883 2439191 8900080334724 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 6 Apollo Bgs Hospitals** Adichunchanagari RoadMysore Kuvempunagar 570023 0821 2566666 8900080330627 Karnataka South Zone 7 Apollo Hospital 13-1-3, Suryaraopeta, MainKakinada Road 533001 0884 2379141 8900080341647 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 8 Apollo Hospitals,Vizag Waltair, Main Road Visakhapatnam 530002 0891 2727272 8900080177710 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 9 Apoorva Hospital 50-17-62 Rajendranagar,Visakhapatnam Near Seethammapeta530016 Jn. 0891 2701258 8900080178007 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 10 Aravindam Orthopaedic Physiotherapy6-18-3, KokkondavariCentre Street,Rajahmundry T. Nagar, Rajahmundry533101 East0883 Godavari2425646 8900080179547 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 11 Asram Hospital (Alluri Sitarama N.H.-5,Raju Academy Malaka OfPuram MedicalEluru Sciences)** 534005 08812 249361-62 8900080180895 -

Telangana List of Hospitals

LIST OF HOSPITALS RECOGNISED BY TS TRANSCO LIMITED (Located in Telangana) S.No. Name of the Hospital 1 Nizams Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad 2 Mahavir Hospital, Hyderabad 3 Kamineni Hospitals Limited, L.B.Nagar, Hyderabad. 4 Mediciti Hospital, Hyderabad (Name changed as Maxcure Hospitals, (A unit of Sahrudaya Healthcare Pvt. Ltd.), 5-9-22, Secretariat Road, Hyderabad Ph. 91 40-2323 1111 5 Durgabai Deshmukh Hospital & Research Centre, Hyderabad (15.07.2013) 6 Apollo Hospital, Jubilee hills, Hyderabad (Deleted) 7 Medwin Hospital, Hyderabad 8 Yashoda Super Speciality Hospital, Malakpet, Hyderabad 9 CDR Hospital, Hyderabad (Deleted) B279 10 CARE Hospital, Nampally, Hyderabad 11 CARE Hospital, Secunderabad. 12 Poulomi Hospital, Rukminipuri Colony, AS Rao Nagar, Main Road, Sec’bad 13 CARE Hospital, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad. (Renewed vide TOO Ms.No.106, dt.17-5-18) 14 Usha Mullapudi Cardiac Centre, Hyderabad. 15 Image Hospital, Ameerpet, Hyderabad. 16 Indo American Cancer Institute & Research Centre , Hyderabad 17 Global Hospital, Lakdi-ka-Phool, Hyderabad 18 Prime Hospitals, Plot No.4, Mytri Vihar, behind Mytri Vanam Building, Ameerpet, Hyderabad. (Earlier Mythri Multi Speciality Hospital) 19 Sri Sai Kidney Centre, Hyderabad 20 Padmavathi Hospital, Hyderabad 21 Smiline Dental Hospitals, Ameerpet Ph.No.237479,23744075, Vikrampuri (Sec’bad) Ph.No.27843434, Santoshnagar Ph.No.24532977 & Jubilee Hills Ph.No.23540279. 22 Rainbow Children’s Hospital, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad. 23 Sathya Kidney Centre & Super Speciality Hospital, Himayat Nagar, Hyderabad. 24 Aditya Hospitals, Tilak Road, Abids, Hyderabad. (Renewed vide TOO Ms.No.17, dt. 4-2-17 25 Sai Krishna Super Speciality Neuro Hospital, Kachiguda, Hyderabad 26 Aware Hospitals, Shanthivanam, Hyderabad, Nagarjunasagar Road. -

1) Network Hospital

1) Network Hospital Sr.No. Name of Hospital Address City State Pin Apollo Hospitals - New No.1, Old No.28, Platform 1 Sheshadripuram (U/o AHEL) Road, Near Mantri Mall, Bangalore Karnataka Sheshadripuram 560020 Aster CMI Hospital No. 43/2, NH-7, Hebbal, 2 Sahakara Nagar,, Bangalore Bangalore Karnataka Kodigehalli Gate, 560092 3 Bangalore Baptist Hospital Bellary Road,Hebbal., Bangalore Karnataka 560024 BGS Global Hospital BGS Health & Education City, 4 No # 67,Uttarahalli road, Bangalore Karnataka Kengeri, 560060 Columbia Asia - Sarjapura Survey No.46/2, Ward No.150,, 5 Bangalore Karnataka Road Ambalipura 560102 Columbia Asia Hospital - Sy No 10P & 12P 6 Whitefield Ramagondanhalli Village, Bangalore Karnataka Varthur Hobli Whitefield 560066 Columbia Asia Medical Kirloskar Buisiness Park Bellary 7 Bangalore Karnataka Centre Road, 560024 COLUMBIA ASIA REFERRAL 26/1,80 feet,Dr. Rajkumar 8 Bangalore Karnataka HOSPITAL- YESHWA Road, Malleshwaram(west) 560055 Fortis Hospitals Ltd - 9 154/9, Bannergatta, Bangalore Karnataka Bannerghatta Road 560076 Fortis Hospitals Ltd - 10 14, Cunningham Road, Bangalore Karnataka Cunningham Road 560052 Fortis Hospitals Ltd - 23 ,80feet Rd,Gurukripalaya 11 Nagarbhavi layout, opp to fab mall,2nd Bangalore Karnataka stage,Nagarbhavi 560072 12 Manipal Hospital 98, Rustom Bagh, Airport Road Bangalore Karnataka 560017 Manipal Hospitals #143, 212-215, EPIP Industrial 13 Whitefield Pvt. Ltd. (MHEPL) Area, Hoodi Village, KR Puram Bangalore Karnataka Hobli 560066 Narayana Hrudayalaya No. 258 / A, Bommasandra 14 Industrial Area, Hosur main Bangalore Karnataka road, Anekal Taluk 560099 People Tree Hospital(Unit of #2, Service Road, Tumkur Road, 15 TMI Health Care Pvt.) (NH-4), Opp.Hotel Vivanta, Bangalore Karnataka Yeshwantpur 560022 Sagar Hospital - Bangalore Shavige Malleshwara Hills, Behind DSI Campus, 16 Bangalore Karnataka Kumaraswamy Layout,Banashankari 560078 Sakra World Hospital No.