Do Dogs Distinguish Rational from Irrational Acts?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Water Spaniel

V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 1 American Water Spaniel Breed: American Water Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: United States First recognized by the AKC: 1940 Purpose:This spaniel was an all-around hunting dog, bred to retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground with relative ease. Parent club website: www.americanwaterspanielclub.org Nutritional recommendations: A true Medium-sized hunter and companion, so attention to healthy skin and heart are important. Visit www.royalcanin.us for recommendations for healthy American Water Spaniels. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 2 Brittany Breed: Brittany Group: Sporting Origin: France (Brittany province) First recognized by the AKC: 1934 Purpose:This spaniel was bred to assist hunters by point- ing and retrieving. He also makes a fine companion. Parent club website: www.clubs.akc.org/brit Nutritional recommendations: Visit www.royalcanin.us for innovative recommendations for your Medium- sized Brittany. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 4 Chesapeake Bay Retriever Breed: Chesapeake Bay Retriever Group: Sporting Origin: Mid-Atlantic United States First recognized by the AKC: 1886 Purpose:This American breed was designed to retrieve waterfowl in adverse weather and rough water. Parent club website: www.amchessieclub.org Nutritional recommendation: Keeping a lean body condition, strong bones and joints, and a keen eye are important nutritional factors for this avid retriever. Visit www.royalcanin.us for the most innovative nutritional recommendations for the different life stages of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 5 Clumber Spaniel Breed: Clumber Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: France First recognized by the AKC: 1878 Purpose:This spaniel was bred for hunting quietly in rough and adverse weather. -

America Debates the Dog's Worth During World War I

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-17-2013 Patriot, Pet, and Pest: America Debates the Dog's Worth During World War I Alison G. Laurence University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Laurence, Alison G., "Patriot, Pet, and Pest: America Debates the Dog's Worth During World War I" (2013). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1644. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1644 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Patriot, Pet, and Pest: America Debates the Dog’s Worth During World War I A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Alison Laurence B.A. -

The Cocker Spaniel Schutzhund Training Walking Down the Aisle

E E R F June 2006 | Volume 3 Issue 6 The Cocker Spaniel Schutzhund Training Walking Down the Aisle with Fido Debunking Common Canine Myths Protecting Family Pets During Domestic Abuse In-FFocus Photography We have a name for people who treat their dogs like children. Customer. There are people who give their dogs commands and those who give them back rubs. There are dogs who are told to stay off the couch and those with a chair at the table. And there are some who believe a dog is a companion and others who call him family. If you see yourself at the end of these lists, you’re not alone. And neither is your dog. We’re Central Visit centralbarkusa.com Bark Doggy Day Care, and we’re as crazy about for the location nearest you. your dog as you are. Franchise opportunities now available. P u b l i s h e r ’ s L e t t e r If your dog is 13 years old (in humane years), is he really 91 years old in dog years? Is the grass your dog eating merely for taste or is it his form of Pepto-Bismol®? When Fido cow- ers behind the couch, does he really know why you're unhappy? There are dozens of myths, or in other words, legends that we as dog lovers either want to believe or simply can't deny. Yet at the end of the day, they are still myths. Flip over to page 18 as we debunk some of the most popular myths found in the canine world. -

Monmouth Boat Club Has Diamond Jubilee

For All Departments Call RED BANK REGISTER RE 6-0013 VOLUME LXXVI, NO. 49 RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, JUNE 3, 1954 10c PER COPY SECTION ONE—PAGES 1 TO 16. Coast Guard Auxiliary to Hold Oceanic Fire Company Celebrates 75th Anniversary Monmouth Boat Club Courtesy Exams This Week-End Has Diamond Jubilee ••- NEW YORK CITY—Roar Ad- This is the diamond jubilee year miral Louis B. Olson, commander save him a g d deal of trouble if of thn Monmouth Boat club cover- of the Coast Guard's eastern area he is inspected later by a regular State Chamber ing 73 years of boating activities. and third Coast Guard district, this Federal Communications commis- Its anniversary program, the birth- week called attention to all pleas- sion official. This check is also day date being May 29, culminates ure boat.owners to the free public rendered as a "courteBy," and no Opposes Bill 9 with thin week's activities. service of the Coast Guard auxili- report Is made to F.C.C. should it The club has Issued a souvenir ary in conducting safety examina- be found that the boat owner has history and roster, 'he introductory tions of pleasure boats. not fully complied with the laws On Teacher Pay page of which carried a message "This season," he said, "presents pertaining to vessel radio stations. from Commodoro Harvey N, a. greator challenge than ever be- Each auxiliary flotilla has its Commissioner Schcnck as follows: fore. Many new boat owners are corps of qualified examiners and "Tho Monmouth Boat club's his- venturing on the waters for the will sponsor certain localities in its Isn't Arbiter, tory over the past 75 years reveals first time with little or no experi- immediate vicinity. -

Use These Color Prints in Conjunction with Match the Correct Breed Names to the Color Prints and Match the Correct Breed Name to Its Specific Traits Situation/Task

89 Breeds Use these color prints in conjunction with Match the correct breed names to the color prints and Match the correct breed name to its specific traits situation/task - tags. statements, and Dog Breeds - Names and Dog Breeds Traits identification Cards, Charts, Diagrwns, Posters. and Prints 90 Beds Use these color prints in conjunction with Match the correct breed names to the color prints and Match the correct breed name to its specifi traits situation/task statements, and Dog Breeds - Names and Dog Breeds - Traits identification tags. Cards. Charts, Diagrams, Posters, and Thints 91 Breeds Use These color prints in conjunction with Match the correct breed names to the color prints and Match the correct breed name to its specific traits situation/task statements, and Dog Breeds - Names and Dog Breeds - Traits identification tags. Cards, Charts, Diagrams, Posters, and P-ints 92 Breeds Use these color prints in conjunction with Match the correct breed names to the color prints and Match the correct breed name to its specific traits situafion/task statements, and Dog Breeds - Names and Dog Breeds - Traits identification tags Cards, Charts, Diagrams, Posters, and PLnts 93 Breeds Use these color prints in conjunction with Match the correct breed names to the color prints and Match the correct breed name to its specific traits situation/task statements, and Dog Breeds - Names and Dog Breeds - Traits identification tags. Canls, Charts, Diagrams, Posters, and Prints 94 Breeds Use these color prints in conjunction with Match the correct breed names to the color prints and Match the correct breed name to its specific traits situation/task statements, and Dog Breeds - Names and Dog Breeds - Traits identification tags. -

Sveriges Hundraser Swedish Breeds of Dogs Sveriges Sweden’S Inhemska Breeds Hundraser of Dogs

Sveriges hundraser Swedish breeds of dogs Sveriges Sweden’s inhemska breeds hundraser of dogs Sverige har elva nationella raser och delar en tolfte med Sweden has eleven national breeds and shares a twelfth Danmark. Åtta av de svenska raserna är erkända av F.C.I. with Denmark. Eight of the Swedish breeds are fully recogni- (Fedération Cynologique Internationale) och den dansk- sed by the F.C.I. (Fedération Cynologique Internationale) svenska gårdshunden blev interimistiskt erkänd 2008. and the Danish-Swedish Farmdog gained preliminary De internationellt erkända jakt- och vallhundsspetsarna recognition in 2008. The Swedish hunting spitzes and i grupp 5 är; svensk lapphund, jämthund, västgötaspets herders in Group 5 that are recognised by the F.C.I. are: och norrbottenspets. Jaktspetsarna, svensk vit älghund Swedish Lapphund, Jämthund, Swedish Vallhund and the och hälleforshund är endast erkända i Sverige. Alla är North Bothnia Spit. Two other hunting spitzes, Swedish ursprungliga raser från den här delen av världen, troligen White Elkhound and Hälleforshund are only recognised in sedan urminnes tider. De drivande raserna i grupp 6 är; Sweden. All are natives to this part of the world since time schillerstövare, hamiltonstövare, smålandsstövare och immortal. The Swedish scent hounds in Group 6 that are drever. Gotlandsstövaren är endast erkänd i Sverige. recognised by the F.C.I. are: Schillerstövare, Hamiltonstö- Den dansk-svenska gårdshunden är av pinschertyp och vare, Smålandsstövare, Drever. The Gotlandsstövare is only finns därmed i grupp 2. recognised in Sweden. The Danish-Swedish Farmdog is of Den första svenska hundrasen blev erkänd 1907, pinscher type, hence in Group 2. det var schillerstövaren. -

Objectives Main Menu Herding Dogs Herding Dogs

12/13/2016 Objectives • To examine the popular species of companion dogs. • To identify the characteristics of common companion dog breeds. • To understand which breeds are appropriate for different settings and uses. 1 2 Main Menu • Herding • Working • Hound Herding Dogs • Sporting • Non-Sporting • Terrier • Toy 3 4 Herding Dogs Herding Dogs • Are born with the instinct to control the • Include the following breeds: movement of animals −Australian Cattle Dog (Blue or Red Heeler) −Australian Shepherd −Collie −Border Collie −German Shepherd −Old English Sheepdog −Shetland Sheepdog −Pyrenean Shepard −Welsh Corgi, Cardigan −Welsh Corgi, Pembroke 5 6 1 12/13/2016 Australian Cattle Dogs Australian Cattle Dog Behavior • Weigh 35 to 45 pounds and • Is characterized by the measure 46 to 51 inches tall following: • Grow short to medium length −alert straight hair which can be −devoted blue, blue merle or red merle −intelligent −loyal in color −powerful • Are born white and gain their −affectionate color within a few weeks −protective of family, home and territory −generally not social with other pets 7 8 Australian Shepherds Australian Shepherds • Males weigh 50 to 65 pounds and measure • Have a natural or docked bobtail 20 to 23 inches in height • Possess blue, amber, hazel, brown or a • Females weigh 40 to 55 pounds and combination eye color measure 18 to 21 inches in height • Grow moderate length hair which can be black, blue merle, red or red merle in color 9 10 Australian Shepherd Behavior Collies • Is characterized by the following: • Weigh -

Measuring Attachments Between Dogs and Their Owners

Measuring Attachments between Dogs and their Owners Submitted by Joanne Wilshaw to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology, September 2010 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following individuals and organisations for their help and support: Alan Brooks of the Guide Dogs for the Blind association Ian Chanter John Dennes and the UK Wolf Conservation Trust Sally Emery Sarah Galley Professor Stephen Lea Professor Peter McGregor Jeri Omlo of Collie Rescue Dr Alan Slater Sally Smart Jean and Keith Wilshaw Grace, Martha and Seth Wilshaw-Chanter 2 Abstract This thesis details the development and testing of a new scale for measuring human attachment to dogs which allows for the measurement of weaker attachment levels as well as stronger ones (the CDA scale). The correlation between dog-owner’s scores on the CDA scale and their dog’s actual attachment behaviour is assessed and discussed, as well as the dog-owners limited ability to predict the behaviour of their dog in a controlled situation (the Strange Situation Test (SST)) whereby the dogs meet a previously unknown person. The CDA scale was formed by utilising items from pre- existing scales (the Comfort from Companion Animals scale and the Lexington Attachment to Pets scale), trialed on the internet with a large self-selected sample of dog-owners and analysed and reduced using factor analysis. -

The T T Times

VOLUME XLXI ISSUE 3 May-June 2017 The T T Times Newsletter of the Tibetan Terrier Club of America President’s M e s s a g e TTCA ESTABLISHES NEW TIBETAN TERRIER PERFORMANCE AWARD As most of you know besides been a show chair know, it is a familiar with. She was loved by being the new President of the daunting job. many and will truly be missed by all. Tibetan Terrier Club of America With that behind me, I will start On a happier note, a thank you (TTCA), I am also the 2017 TTCA out with the sad news, which many of needs to go out to the committee led National Specialty Show Chairman. you have already heard, which is the by Claire Coppola who has been The reason I am noting this is to start passing of our fellow member Pat working so hard on the new “TTCA Versatile Companion Dog Awards.” out apologizing in case this message Nelson on April 8. Our last newsletter is missing some of the new and shared about some of her The area of performance has not important club activities that have accomplishments. Though I never received the attention that I and occurred in the past couple of had the privilege of meeting her, the many others feel it deserves. You months. I have tried to stay on top of impact of her love and dedication to will find an article in this newsletter things, but as any of you who have the breed was something I was very (Continued on page 3) THE TIBETAN TERRIER CLUB OF Deadline for Next Issue Please submit content for the next AMERICA (TTCA) issue of The TT Times by July 1. -

THE PEKINGESE ORIGIN: Pekingese Hail From

THE PEKINGESE ORIGIN: Pekingese hail from the ancient city of Peking, China, now known as Beijing. They were originally bred as a lap dog, watch dog, and companion dog. They are regarded as one of the oldest breeds of dogs. Only the royal class of China was allowed to own a Pekingese. In fact, commoners had to bow to them, and you could be punished by death if you stole one. When an emperor died, his Pekingese was sacrificed so it could go with him to give protection in the afterlife. In 1860, British and French troops overran the Summer Palace during the Second Opium War, and the Imperial Guards who protected the palace were ordered to kill the little dogs to prevent them from falling into the hands of the “foreign devils.” However, five puppies were rescued and given to Queen Victoria. One of the puppies was aptly named “Looty”. It was from these five puppies that the modern Pekingese was formed. They were first recognized in America in 1909. The pronunciation is PEKE-in-ese. PERSONALITY: The Pekingese is brave, self-assured, and independent. They can be extremely affectionate with their owner but wary of strangers. The breed is good with kids as well as other dogs and pets. However, as with any dog, you must teach young children how to properly play with them to avoid any unintentional injuries. Pekingese can be a little difficult to train. A firm and consistent touch is necessary. They are moderately active which makes them ideal for an apartment lifestyle and indoor living. -

2019 CDSP National Rankings

2019 National Rankings Companion Dog Sports Program Starter Novice Top 20 Starter Novice A Rank 1 Border Collie SR Lite D'Lamp Jackson Deb District of Col 2 Golden Retriever Milbrose The Sun Will Shine Once More Swainamer Charlene New Hampshire 3 Labrador Retriever RLZ Times Two Dunn's Marsh Honest Abe Papalia Anne Pennsylvania 4 Doberman Pinscher Crosspointe's Freya Baroni Terry Florida 5 Boston Terrier Let's Catch The Wind On The Charles Cotter, DVM Susan Massachusetts 6 Australian Shepherd Coolibah Better's Best Ace-A-Spades Miles Nancy Florida 7* Shetland Sheepdog (Sheltie) Amber Hill Surf Dancer Hendrickson Anne Massachusetts 7* West Highland White Terrier Borgo's Glorious Shamrock Of Whiteheather Lowden Mary Minnesota 8 Standard Poodle Bella's Lumiere Dirty Harry Norby Linda Florida 9 Portuguese Water Dog Bayswater's Hops And Barley Halsema Beth Indiana 10 Jack Russell Terrier Fleet Street Mister Wilson Ver Sprill Sandi New Jersey 11* Border Collie Poppy Tamman Patricia Florida 11* Border Collie Black Gemstone Kline Lana Pennsylvania 11* English Setter Rocking T Rowan Combs Donna Pennsylvania 12 Nova Scotia Duck Tollling Retriever Baxter Uno Geddis Colleen New Jersey 13* Australian Shepherd Owinto Coco Chanel's Camellia Owings Clare Maryland 13* German Shepherd Dog Jesse Pascucci Elizabeth Pennsylvania 14 Golden Retriever PRR's Better Be Good Droukas Nancy Massachusetts 15 All American Hakuna Matata Fredrickson Danielle Wisconson 16* Briard Tintagel's Faith De Beardsanbrow McMahon Elise Massachusetts 16* Golden Retriever Sunfire's -

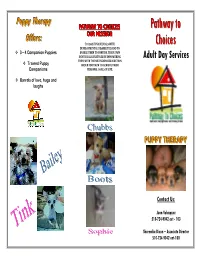

Pathwayto Choices

PPuuppppyy TThheerraappyy PPPPPPAAAAAATTTTTTHHHHHHWWWWWWAAAAAAYYYYYY TTTTTTOOOOOO CCCCCCHHHHHHOOOOOOIIIIIICCCCCCEEEEEESSSSSS PPaatthhwwaayy ttoo OOOOOOUUUUUURRRRRR MMMMMMIIIIIISSSSSSSSSSSSIIIIIIOOOOOONNNNNN OOffffeerrss:: TO ASSIST INDIVIDUALS WITH CChhooiicceess DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES AND TO 3 – 4 Companion Puppies ENABLE THEM TO CONTROL THEIR OWN INDIVIDUAL LIFESTYLES BY EMPOWERING Adult Day Services THEM WITH THE NECESSARY RESOURCES IN Trained Puppy ORDER FOR THEM TO ACHIEVE THEIR Companions PERSONAL GOALS IN LIFE. Barrels of love, hugs and laughs PPUUPPPPYY TTHHEERRAAPPYY “Boots” “Sophie” Contact Us: Juan Velasquez 510-724-9042 ext - 103 Shermeka Dixon – Associate Director 510-724-9042 ext-100 PPPPPPaaaaaattttttttthhhhhhwwwwwwaaaaaayyyyyy tttttttttoooooo CCCCCChhhhhhooooooiiiiiiiiicccccceeeeeessssss brings the Present day Yorkies are a new community together fad for lots of celebs. They carry Yorkies through friendly, around in special purses. One unique loveable companion characteristic of a Yorkies is that they puppiespuppies.... are great with children. FFFFFFeeeeeeaaaaaattttttuuuuuurrrrrriiiiiiiiinnnnnngggggg:::::: She is a 3-year-old teacup Chihuahua. She has had two litters of puppies, 3 the first and 4 the second. She was a He is a 8-year-old teacup Yorkie. wonderful mother and sees all her pups The Yorkshire terrier is a small dog often. breed . He is very quiet and wants to be loved. He has well adjusted to both people and animals. He follows his Through folklore and archeological owner everywhere if allowed to and is finds, there is so content just keeping someone evidence that the company. He absolutely loves car rides breed originated and the idea of getting in and getting out in Mexico. The at a new destination. I would Mamaz is a Yorkie and Silky most common recommend this breed to anyone. Terrier. She is 1½-year-old and she is theory is that going through intensive training to Chihuahuas are descended from the OOuurr PPuuppppyy CCoommppaanniiioonnss become a companion dog.