The Signature of Hip Hop: a Sociological Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

TranscUlturAl, vol. 6.1 (2014), 70-83. http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/TC Conflicts of Interest, Culture Jamming and Subversive (S)ignifications: The High Fashion Logo as Locational Hip Hop Articulation Rebecca Halliday York University In the fall of 2012, an unheard of fashion label called “Conflict of Interest NYC” (C.O.I.) released three black and white, unisex t-shirts for sale online. Each t-shirt took the brand name and/or logo of a storied fashion house – Balenciaga, Bottega Veneta and Givenchy – and imposed a set of urban and sexualized representations and hip hop references to enact a high-end-low-end subversion of the brand’s connotations. The t-shirts came to public attention after Internet “street style” photographer Tommy Ton captured New York fashion editor Shiona Turini wearing a BALLINCIAGA t-shirt on the street at London Fashion Week and posted it on Condé Nast Media’s fashion bible Style.com. This article contextualizes the t-shirts within historical interactions between fashion and hip hop culture and reads the BALLINCIAGA t-shirt for its intertextual connections to hip hop and black oral tradition.1 In this sense, my analysis constitutes a “translation” of and between sets of cultural “codes” (Hall 21): in this instance, a translation of fashion brand names and subcultural references. Conflict of Interest’s t-shirts present a sophisticated incidence of culture jamming that parodies high fashion brands through hip hop references; it thus criticizes high fashion’s historical Eurocentric elitism and articulates urban conditions. While the t-shirts were not created as an explicit political protest, they are indeed subversive, and their creation and proliferation from within fashion illuminates the politics of fashion’s cultural appropriations and socioeconomic identities. -

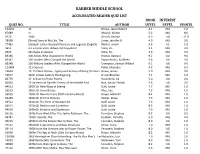

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

Global Hip-Hop Class

AAAS 135b: GLOBAL HIP-HOP Wed 6:30-9:20 pm Mandel G03 Spring 2012 Wayne Marshall [email protected] office hours: by appointment DESCRIPTION Examining how hip-hop travels and is embraced, represented, and transformed in various locales around the world, this course approaches hip-hop as itself constituted by international flows and as a product and set of practices that circulate globally in complex ways, cast variously as American, African-American, and/or black, and recast through the cultural logics of the new spaces it enters, the soundscapes it permeates. A host of questions arise when we consider hip-hopʼs global scope and significance: What does the genre in its various forms (audio, video, sartorial, gestural) carry beyond the US? What do people bring to it in new local contexts? How are US notions of race and nation mediated by hip-hop's global reach? Why do some global (which is to say, local) hip-hop scenes fasten onto the genre's well-rehearsed focus on place, community, and righteous opposition to structural and representational forms of violence, while others appear more enamored with slick portrayals of hustler archetypes, cool machismo, and ruggedly individualist, conspicuous consumption? How can hip-hop circulate in such contradictory forms? In what ways do hip-hop scenes differ from North to South America, West to East Africa, Europe to Asia? What threads unite them? In pursuit of such questions, we will read across the emerging literature on global hip- hop as we explore the growing resources available via the internet, where websites and blogs, MySpace and YouTube and the like have facilitated a further efflorescence of international (and peer-to-peer) exchanges around hip-hop. -

DJ Skills the Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3

The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 1 74 The Rise of The Hip-hop DJ DJs were Hip-hop’s original architects, and remain crucial to its contin- ued development. Hip-hop is more than a style of music; it’s a culture. As with any culture, there are various artistic expressions of Hip-hop, the four principal expressions being: • visual art (graffiti) • dance (breaking, rocking, locking, and popping, collectively known in the media as “break dancing”) • literature (rap lyrics and slam poetry) • music (DJing and turntablism) Unlike the European Renaissance or the Ming Dynasty, Hip-hop is a culture that is very much alive and still evolving. Some argue that Hip-hop is the most influential cultural movement in history, point- ing to the globalization of Hip-hop music, fashion, and other forms of expression. Style has always been at the forefront of Hip-hop. Improvisation is called free styling, whether in rap, turntablism, breaking, or graf- fiti writing. Since everyone is using the essentially same tools (spray paint for graffiti writers, microphones for rappers and beat boxers, their bodies for dancers, and two turntables with a mixer for DJs), it’s the artists’ personal styles that set them apart. It’s no coincidence that two of the most authentic movies about the genesis of the move- ment are titled Wild Style and Style Wars. There are also many styles of writing the word “Hip-hop.” The mainstream media most often oscillates between “hip-hop” and “hip hop.” The Hiphop Archive at Harvard writes “Hiphop” as one word, 2 DJ Skills The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3 with a capital H, embracing KRS-ONE’s line of reasoning that “Hiphop Kool DJ Herc is a culture with its own foundation narrative, history, natives, and 7 In 1955 in Jamaica, a young woman from the parish of Saint Mary mission.” After a great deal of input from many people in the Hip-hop community, I’ve decided to capitalize the word but keep the hyphen, gave birth to a son who would become the father of Hip-hop. -

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

Suriano.Pmd 113 01/12/2011, 15:11 114 Africa Development, Vol

Africa Development, Vol. XXXVI, Nos 3 & 4, 2011, pp. 113–126 © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, 2011 (ISSN 0850-3907) Hip-Hop and Bongo Flavour Music in Contemporary Tanzania:Youths’ Experiences, Agency, Aspirations and Contradictions1 Maria Suriano* Abnstract The beginning of Tanzanian hip-hop along with a genre known as Bongo Flavour (also Bongo Flava, or Fleva, according to the Swahili spelling), can be traced back to the early 1990s. This music, characterised by the use of Swahili lyrics (with a few English and slang words) is also re- ferred to as the ‘music of the new generation’ (muziki wa kikazi kipya). Without the intention to analyse a complex and multifaceted reality, this article aims to make a sense of this popular music as an overall phenom- enon in contemporary Tanzania. From the premise that music, perform- ance and popular culture can be used as instruments to innovate and produce change, this article argues that Bongo Flavour and hip-hop are not only music genres, but also cultural expressions necessary for the understanding of a substantial part of contemporary Tanzanian youths. The focus here is on young male artists living in urban environments. Résumé Le début du hip-hop en Tanzanie ainsi que d’un genre musical appelé Bongo Flavour (aussi Bongo Flava ou Fleva, selon l’orthographe en Swahili) date du début des années 1990. Caractérisée par l’utilisation de textes en swahili (avec quelques mots en anglais et en argot), cette musique est considérée comme ‘la musique de la nouvelle génération’ (muziki wa kikazi kipya). -

Afrofuturism, Critical Race Theory, and Policing in the Year 2044 I

Brooklyn Law School Legal Studies Research Papers Accepted Paper Series Research Paper No. 586 February 2019 Afrofuturism, Critical Race Theory, and Policing in the Year 2044 I. Bennett Capers This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract=3331295 CAPERS-LIVE(DO NOT DELETE) 2/7/19 7:58 PM ARTICLES AFROFUTURISM, CRITICAL RACE THEORY, AND POLICING IN THE YEAR 2044 I. BENNETT CAPERS* In 2044, the United States is projected to become a “majority- minority” country, with people of color making up more than half of the population. And yet in the public imagination— from Robocop to Minority Report, from Star Trek to Star Wars, from A Clockwork Orange to 1984 to Brave New World—the future is usually envisioned as majority white. What might the future look like in year 2044, when people of color make up the majority in terms of numbers, or in the ensuing years, when they also wield the majority of political and economic power? And specifically, what might policing look like? This Article attempts to answer these questions by examining how artists, cybertheorists, and speculative scholars of color— Afrofuturists and Critical Race Theorists—have imagined the future. What can we learn from Afrofuturism, the term given to “speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns [in the context of] techno culture?” And what can we learn from Critical Race Theory and its “father” Derrick Bell, who famously wrote of space explorers to examine issues of race and law? What do they imagine policing to be, and what can we imagine policing to be in a brown and black world? ∗ Copyright © 2019 by I. -

A DJ Perspective Paul Bell Submitted in Fulfilment of the Degree of Phd

Interrogating the Live: A DJ Perspective [Electronic Version] Paul Bell Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD, Newcastle University, 2009 i ii Contents Preface……………………………………………………………………........vi List of Media……………………………………………………………………ix Introduction…………………………………………………………………… xiii Chapter 1: Orientation – The Live and the Recorded……………………...1 1.1. The Poles of the Live and the Recorded…………………………….1 1.2. Technological Permeation………………………………………...... ..5 1.3. Live Electronic Music…………………………………………………..9 Chapter 2: Improvisation and Recording………………………………….. 14 2.1. Why Document? …………………………………………………….. 14 2.2. The Paradox in Documenting Improvisation……………………… 15 2.3. How to Document? ………………………………………………….. 17 2.4. Editing Improvisation………………………………………………… 24 Chapter 3: Gesture and Interface………………………………………….. 29 3.1. Sound as Gesture…………………………………………………… 29 3.2. The Body and the Machine…………………………………………. 31 3.3. Gesture and Interface……………………………………………….. 34 3.4. To Cause or Not to Cause: Music Technologies vs. Musical Instruments…………………………………………………………… 37 3.5. Digital DJ Tools………………………………………………………. 39 3.6. Practical Projects…………………………………………………….. 44 3.6.1. Anti Telos……………………………………………………………... 44 3.6.2. Video and Gesture…………………………………………………… 46 iii 3.7. Considering Immediacy in Digital Media………………………….. 49 Chapter 4: Negotiating Unpredictability…………………………………… 52 4.1. The Creative Process……………………………………………...... 52 4.2. Relinquishing Control………………………………………………... 55 4.3. A Virtuosity in Finding……………………………………………...... 56 4.4. Indeterminacy vs. -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black ..................................