Toward Clarification of New Mexico's Real Property Statutes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Which Deed Should I Use?

FEATURE | TITLEREAL ESTATE LAW Which Deed Should I Use? BY EBEN P. CLARK 34 | COLORADO LAWYER | JANUARY 2019 Tis article discusses the four basic deed forms used in Colorado and when to use each form. hich deed should I use? Tis is c. Tat he warrants to the grantee and his the inevitable question in any heirs and assigns the quiet and peaceable transaction in which real prop- “ possession of such property and will erty is conveyed, regardless of The four basic defend the title thereto against all persons theW form of the transaction or the property to be who may lawfully claim the same. transferred. Every lawyer, realtor, or other real deed forms in While Upton and the Colorado Revised estate professional has faced this question at Statutes lay out with particularity the warranties some point in time. Colorado are included with a general warranty deed, for This article provides an overview of the general warranty, comparison purposes it is worth noting that at diferent types of deed forms available in Col- common law, the standard warranties of title orado. It describes the basic characteristics of special warranty, were referred to as six covenants: each type of deed, and its appropriateness for 1. the covenant of seisin (that the grantor various circumstances. Tis article does not bargain and sale, has the very estate it purports to convey); advocate for the use of a single form of deed for 2. the covenant of right to convey (that a certain transaction. Nor does it seek to provide and quitclaim. the grantor has the right to convey the a formula for determining the appropriate In this order, promised title); deed form in any specifc situation. -

Right of Way Manual, Section 4.1, Land Title

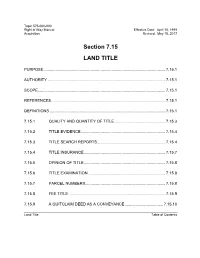

Topic 575-000-000 Right of Way Manual Effective Date: April 15, 1999 Acquisition Revised: May 18, 2017 Section 7.15 LAND TITLE PURPOSE ............................................................................................................... 7.15.1 AUTHORITY ........................................................................................................... 7.15.1 SCOPE .................................................................................................................... 7.15.1 REFERENCES ........................................................................................................ 7.15.1 DEFINITIONS ......................................................................................................... 7.15.1 7.15.1 QUALITY AND QUANTITY OF TITLE .............................................. 7.15.3 7.15.2 TITLE EVIDENCE ............................................................................. 7.15.4 7.15.3 TITLE SEARCH REPORTS .............................................................. 7.15.4 7.15.4 TITLE INSURANCE .......................................................................... 7.15.7 7.15.5 OPINION OF TITLE .......................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.6 TITLE EXAMINATION ...................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.7 PARCEL NUMBERS......................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.8 FEE TITLE ....................................................................................... -

Chapter 12 Questions Transfer of Title

Modern Real Estate Practice, 18th Edition Chapter 12 Questions Transfer of Title 1. The title to real estate passes when a valid deed is a. signed and recorded. b. delivered and accepted. c. filed and microfilmed. d. executed and mailed. 2. The primary purpose of a deed is to a. prove ownership. b. transfer title rights. c. give constructive notice. d. prevent adverse possession. 3. A special warranty deed differs from a general warranty deed in that the grantor's covenant in the special warranty deed a. applies only to a definite limited time. b. covers the time back to the original title. c. is implied and is not written in full. d. protects all subsequent owners of the property. 4. The severalty owner of a parcel of land sells it to a buyer. The buyer insists that the owner's wife join in signing the deed. The purpose of obtaining the wife's signature is to a. waive any marital or homestead rights. b. defeat any curtesy rights. c. provide evidence that the owner is married. d. satisfy the parol evidence rule. 5. A third party holds title to property on behalf of someone else through the use of a a. devise. b. quitclaim deed. c. bequest. d. deed in trust. ©2010 Kaplan, Inc. Modern Real Estate Practice, 18th Edition 6. In a real estate transaction, transfer taxes that are due are charged a. to the buyer unless this is forbidden by statute or regulation. b. according to local custom unless the parties are from different jurisdictions. c. to the parties as agreed in the contract of sale. -

Contract of Sale—Condominium Unit

Contract of Sale—Condominium Unit Note: This form is intended to deal with matters common to most transactions involving the sale of a condominium unit. Provisions should be added, altered or deleted to suit the circumstances of a particular transaction. No representation is made that this form of contract complies with Section 5-702 of the General Obligations Law (“Plain Language Law”). In the event of any alteration to this form which is not clearly indicated as such, the provisions of the original unaltered form as approved by the Cooperative & Condominium Law Committee of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York and the Committee of Condominiums & Cooperatives of the Real Property Law Section of the New York State Bar Association shall be deemed controlling, regardless of such change. CONSULT YOUR LAWYER BEFORE SIGNING THIS AGREEMENT This Contract (the “Contract”) for the sale of the Unit as defined below is made as of ____________________ between “Seller” and “Purchaser” identified below. 1. Certain Definitions and Information 1.1 The “Parties” (each a “Party”) are: 1.1.1 “Seller”: Prior names used by Seller: Address: 1.1.2 “Purchaser”: Prior names used by Purchaser: Address: (For security, social security numbers are not included on this form but shall be provided to the attorneys for the Parties upon request.) 1.2 “Attorneys” (each an “Attorney”) are (name, address telephone and email): 1.2.1 “Seller’s Attorney”: 1.2.2 “Purchaser’s Attorney”: 1.3 “Escrowee” is the [Seller’s] [Purchaser’s] Attorney [or Title Company] (as -

Chapter 8 – Deeds & Transfer of Title

CHAPTER 8 – DEEDS & TRANSFER OF TITLE An * in the left margin indicates a change in the statute, rule or text since the last publication of the manual. Before the modern-day concept of land ownership, title to real estate was evidenced primarily by possession of the land and the power to defend the land against others. The earliest method of transferring title to real property was simply surrender of possession by the claimant to another. The use of deeds to convey real property has a long and colorful history. Personal property has always transferred by giving possession of the thing itself. In feudal land transfers, the seller presented a clod of dirt from the land to the buyer in the presence of witnesses to symbolize delivery of title. Today, the delivery of the deed constitutes the actual transfer of title to the land. Title to real property transfers from one person to another by one of four general means: (1) descent; (2) will; (3) involuntary alienation; or (4) voluntary alienation. Title transfers by descent when a person dies without leaving a will (intestate). All states have statutes of descent and distribution providing for the orderly disposition of real property for those who die intestate. Such statutes typically distribute property to the nearest relatives, on the presumption that this would have been the desire of the deceased. According to the Colorado Probate Code, a portion of which is printed below, distribution of the largest share of the property of the intestate, and never less than half of the estate, descends to the surviving spouse. -

Real Estate II: Issues in Ownership of Real Property

Global Practice Guide Real Estate II: Issues in Ownership of Real Property A Global Practice Guide prepared by the Lex Mundi Real Estate Group This guide is part of the Lex Mundi Global Practice Guide Series which features substantive overviews of laws, practice areas, and legal and business issues in jurisdictions around the globe. View the complete series at: www.lexmundi.com/GlobalPracticeGuides. Lex Mundi is the world’s leading network of independent law firms with in-depth experience in 100+ countries. Through close collaboration, our member firms are able to offer their clients preferred access to more than 21,000 lawyers worldwide – a global resource of unmatched breadth and depth. Lex Mundi – the law firms that know your markets. www.lexmundi.com About this Guide This multi-part Guide of Issues in Real Estate Investment and Finance presents jurisdictional overviews of real estate investment and financing laws in jurisdictions around the world, covering the following four general topics: Part I -- Foreign Investment Part II -- Ownership of Real Property Part III – Finance Part IV – Leasing Table of Contents Argentina ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Austria .......................................................................................................................................... -

82 GENERAL LAWS Whan Act to SEC, 2. This Act Shall Take Effect and Be in Force from and Uke Effect

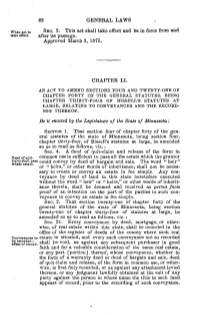

82 GENERAL LAWS Whan act to SEC, 2. This act shall take effect and be in force from and uke effect. after its passage. Approved March 3, 1875. CHAPTER LI. AN ACT TO AMEND SECTIONS FOUR AND TWENTY-ONE OF CHAPTER FORTY OB1 THE GENERAL STATUTES, BEING CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR OF BISSELL'S STATUTES AT LARGE, RELATING TO CONVEYANCES AND THE RECORD- ING THEREOF. Be it enacted by the Legislature of the State of Minnesota : SECTION 1. That section four of chapter forty of the gen- eral statutes of the state of Minnesota, being section four, chapter thirty-four, of Bissell's statutes at large, be amended so as to read as follows, viz.: Sec. 4. A deed of quit-claim and release of the form in Deed of quit- common usois sufficient to pass all the estate which the grantor claimshn.iipans could convey by deed of bargain and sale. The word "heir" whole estate. or ", , heirs• , ,, or othe,1 r word-,s of« inheritance• i , shal11. l no,t ,be neces- sary to create or convey an estate in fee simple. Any con- veyance by deed of land in this state heretofore executed without the word " heir" or " heirs," or other words of inherit- ance therein, shall be deemed and received as prima facie proof of an intention on the part of the parties to such con- veyance to convey an estate in fee simple. SEC. 2. That section twenty-one of chapter forty of the general statutes of the state of Minnesota, being section twenty-one of chapter thirty-four of statutes at large, be amended so as to read as follows, viz.: Sec. -

WATER DUE DILIGENCE: What Real Estate Attorneys Should Understand

WATER DUE DILIGENCE: What real estate attorneys should understand about water rights due diligence when their clients are purchasing property with water rights I. A brief history of salient Colorado water laws: A. In Colorado, we rejected the riparian doctrine of water rights early on. That doctrine holds that if you own land adjacent to a stream, you can make a reasonable use of the water flowing through your land. a. This did not make sense in Colorado because one must often transport water far from a stream to make land productive, because we do not have sufficient rainfall. B. 1861 the Territorial Legislature provided that water could be taken from the streams to lands not adjacent to streams. C. In 1872, the Colorado Territorial Supreme Court recognized rights of way (easements), citing custom and necessity, through the lands of others for ditches carrying irrigation water to its place of use. Yunker v. Nichols, 1 Colo. 551, 570 (1872) D. In 1876 the Colorado Constitution declared: a. “The water of every natural stream, not heretofore appropriated, within the state of Colorado, is hereby declared to be the property of the public, and the same is dedicated to the use of the people of the state, subject to appropriation as hereinafter provided.” Const. of Colo., Art. XVI, Sec. 5. b. “The right to divert the unappropriated waters of any natural stream to beneficial uses shall never be denied. Priority of appropriation shall give the better right as between those using the water….” Const. of Colo., Art. XVI, Sec. 6 c. All persons and corporations shall have the right-of-way across public, private and corporate lands for the construction of ditches, canals and flumes for the purpose of conveying water for domestic purposes, for the irrigation of agricultural lands, and for mining and manufacturing purposes, and for drainage, upon payment of just compensation.” -Const. -

1 / an Introduction to the Real Estate Business

Quiz 27: Transfer of Title 1. In a real estate transaction, transfer taxes that are due are charged a. to the buyer unless this is forbidden by statute or regulation. b. according to local custom unless the parties are from different jurisdictions. c. to the parties as agreed in the contract of sale. d. to the closing agent and real estate broker if the contract does not specify who pays. 2. The title to real estate passes when a valid deed is a. signed and recorded. c. filed and microfilmed. b. delivered and accepted. d. executed and mailed. 3. The severalty/single owner of a parcel of land sells to a buyer. The buyer insists that the owner's wife join in signing the deed. The purpose of obtaining the wife's signature is to a. waive any marital or homestead rights. b. defeat any curtesy rights. c. provide evidence that the owner is married. d. satisfy the parol evidence rule. 4. A third party holds title to property on behalf of someone else through the use of a a. devise. c. bequest. b. quitclaim deed. d. deed in trust. 5. The primary purpose of a deed is to a. prove ownership. c. give constructive notice. b. transfer title rights. d. prevent adverse possession. 6. Which of the following documents is signed by the owner of the real estate? a. A gift deed c. A reconveyance deed b. A trustee's deed d. A tax deed 7. A special warranty deed differs from a general warranty deed in that the grantor's covenant in the special warranty deed a. -

When It Comes to Deeds, It Pays to Pay Attention by Evan L

SEPTEMBER 20, 2002 When it comes to deeds, it pays to pay attention By Evan L. Randall protection against encumbrances upon or inter- seller later acquires title to the property, the Old habits die hard. And they can be expen- ests in the property unknown to the seller and seller’s after acquired title will automatically sive, especially when buying property in Colo- created before the seller acquired title. transfer to the buyer by virtue of the previously rado. Blindly agreeing to the commonly used Thus, the general warranty deed provides delivered deed. general warranty deed to seal your transaction the greatest protection to the buyer. If the buyer may come back to haunt you in later years. (or a successor in interest) suffers a loss because Quitclaim Deeds Similar to a bargain and sale deed, a quitclaim When buying property in Colorado, it pays to of an adverse title matter covered by the seller’s deed does not contain any warranties. A quit- pay attention to what kind of deed you’re sign- warranty, the buyer has the right to bring a claim against the seller. claim deed, however, will not transfer the seller’s ing. after acquired title in the property. Because of Whether you’re a buyer or a seller, it’s im- Special Warranty Deeds these limitations, buyers are usually reluctant portant to understand the types of deeds avail- In residential transactions, it is still common to accept a quitclaim deed in a normal property able, since the contract typically will specify to convey property by general warranty deeds. -

Chapter 10 Summary Deeds

Chapter 10 Summary Deeds Voluntary alienation is an unforced transfer of title by sale or gift from an owner to another party. Involuntary alienation is a transfer of title to real property without the owner's consent. DEEDS • Grantor - The person who transfers the title to real property. • Grantee - The person who receives the property from the grantor. • Act of conveyance - Expresses the grantor's present desire and intention to transfer legal title to the grantee (granting clause). • Consideration - Valuable or good consideration. • Legal description - Accurately locates and identifies the boundaries of the subject parcel of property. • Habendum clause - Describes the type of estate being conveyed. • Designation of limitations - Limitations spelled out in the deed. • Exemptions and reservations affecting the title - A "subject to" clause. • Signature of the grantor - Must be signed by the grantor, but not necessarily by the grantee. • Delivery and acceptance of the deed - Necessary for title to pass. • Acknowledgement - A deed without an acknowledgement tends to endanger a person's claim to a property. • Recording - Not necessary, but gives the public constructive notice of the grantee's ownership. LEGAL DESCRIPTIONS A legal description provides accuracy and consistency over time. It is required for: • Public recording • Creating a valid deed of conveyance or lease • Completing mortgage documents • Executing and recording other legal documents Metes and Bounds • Identifies the boundaries of a parcel of real estate using reference points, distances, and angles. The description always identifies an enclosed area by starting at and returning to the POB. 1 Chapter 10 Summary Deeds Rectangular Survey System Based on sets of intersecting lines principal meridians run north and south; base parallels run east and west. -

Legal Aspects of Real Estate

LEGAL ASPECTS OF REAL ESTATE A DEFINITION OF REAL PROPERTY There are, in the legal sense, two basic classes of property: (1) real property, sometimes referred to as real estate; and (2) personal property. In general and perhaps oversimplified terms, the difference between the two is that real property has to do with an interest in the land itself or something firmly affixed thereto, whereas personal property is readily movable from one place to another. In more specific terms, there are many other distinctions between real property and personal property. Title to real property, for example, is conveyed by means of a legal document known as a deed. An item of personal property normally referred to as a chattel is, on the other hand, commonly transferred by virtue of a bill of sale, or simply by delivery of possession. In a general sense, then, real property may be defined as the land itself, including, under normal circumstances, everything attached to or growing from the earth, whether through the course of nature or as a result of man7s construction. It is, however, more than this. As stated the federal courts in the 1945 case of Causby v.United States: Under the old common law doctrine ... a land owner not only owns the surface of his land, but also owns all that lies beneath the surface even to the bowels of the earth and all the air space above it even unto the periphery of the sky In theory, therefore, ownership of land means ownership of a triangle with its apex at the center of the earth and its base extending upward to infinity.