An Economic Analysis of Madison County in Northwest Arkansas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Agricultural Practices on Nutrient Concentrations and Loads in Two Small Watersheds, Northwestern Arkansas Robin G

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 52 Article 15 1998 Effects of Agricultural Practices on Nutrient Concentrations and Loads in Two Small Watersheds, Northwestern Arkansas Robin G. Roggio University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Kenneth F. Steele University of Arkansas, Fayetteville P. F. Vendrell University of Arkansas, Fayetteville M. A. Nelson University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Environmental Monitoring Commons, Fresh Water Studies Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Roggio, Robin G.; Steele, Kenneth F.; Vendrell, P. F.; and Nelson, M. A. (1998) "Effects of Agricultural Practices on Nutrient Concentrations and Loads in Two Small Watersheds, Northwestern Arkansas," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 52 , Article 15. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol52/iss1/15 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 52 [1998], Art. 15 Effects of Agricultural Practices on Nutrient Concentrations and Loads in Two Small Watersheds, Northwestern Arkansas Robin G. -

Revised Bedrock Geology of War Eagle Quadrangle, Benton County, Arkansas Robert A

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 56 Article 27 2002 Revised Bedrock Geology of War Eagle Quadrangle, Benton County, Arkansas Robert A. Sullivan University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Stephen K. Boss University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Geographic Information Sciences Commons, and the Stratigraphy Commons Recommended Citation Sullivan, Robert A. and Boss, Stephen K. (2002) "Revised Bedrock Geology of War Eagle Quadrangle, Benton County, Arkansas," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 56 , Article 27. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol56/iss1/27 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 56 [2002], Art. 27 Revised Bedrock Geology of War Eagle Quadrangle, Benton County, Arkansas Robert A. Sullivan and Stephen K.Boss* Department of Geosciences 113 Ozark Hall University of Arkansas Fayetteville, AR 72701 ¦"Corresponding Author Abstract A digital geologic map of War Eagle quadrangle (WEQ) was produced at the 1:24000 scale using the geographic information system (GIS) software ArcView® by digitizing geological contacts onto the United States Geological Survey (USGS) digital raster graphic (DRG). -

Beaver Watershed Alliance Food Sources, and Holistic Community Quality USDA NRCS to Manage Vegetation (Nrcs.Usda

Sugar 62 Loaf Panorama 187 Bella L Point 72 Elkhorn Williams Devil’s Eye Brow BB EE AAVista VV EE RR Natural Area LL AA KK EE Pea Ridge National Henry Trimble Round Military Indian Lake Pea Park Creek 187 Leatherwood WATERSHEDS Glasscock Gentry WATERSHEDS BENTON Ridge CARROL Watersheds are separated BEAVER LAKE WATERSHED Garfield Dam Site River Park by topographic divides off Source water from 7 sub-watersheds Rich Dam Site North Park which water flows to one side flows into Beaver Lake/White River. or the other. Beaver Lake- Indian Creek Park USACE/Beaver Dam 187 White River WS 62 Humphery Dam Site Lake Park Lake Sequoyah-WR WS Pond Beaver Dam Middle Fork-WR WS 94 Carroll-Boone Water District War Eagle Lost Bridge Public Rolloff West Fork-WR WS Creek WS Avoca Lost Miles Richland Creek Use Area Creek WS “Two Ton” Benton/Washington Bridge Hollow Sugar Headwaters of Posy Regional Public Ford WR WS Water Authority Village Starkey Public Use Area 62 Coose Little Flock Hollow Like stacking bowls, a watershed W may be part of one that is larger and W Grindstone also have any number of smaller Prairie Creek Ventris “SUB-WATERSHEDS” inside it. Beaver Lake Park Pond The WHITE RIVER flows 722 miles from Project Office North its HEADWATERS near Boston, Arkansas in Larue the Beaver Lake Watershed, Clifty northward into Missouri, then Prairie 23 Creek south to the lowest point in Lake Creek 3D21 Buck its watershed where it joins Atalanta Rocky Branch the Arkansas RIver, ultimately Former 12 Park draining into the MISSISSIPPI Water Supply RIVER. -

An Economic Analysis of Benton County in Northwest Arkansas

AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF BENTON COUNTY IN NORTHWEST ARKANSAS Center for Business and Economic Research Reynolds Center Building 217 Sam M. Walton College of Business 1 University of Arkansas Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701-1201 (479) 575-4151 August 30, 2002 1 An Economic Analysis of Benton County in Northwest Arkansas I. Geographic Description Benton County is comprised of 846 square miles and borders Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma in the northwest corner of the state in the Springfield Plateau physiographic region. Figure 1 highlights the counties that comprise the Norwest Arkansas region, as defined by the Arkansas Department of Economic Development. Benton County is shown in red; all other counties in the region are shown in yellow. Figure 1 – Benton County’s Location The extreme southeastern region of the county is comprised of the Ozark National Forest. The county is also home to Beaver Lake, located in the eastern portion of the county, and Pea Ridge National Military Park, located in the northeast portion of the county. Sources: United States Census Bureau. State and County QuickFacts. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/05/05005.html Chart 2-5: Physiographic Regions. Arkansas Statistical Abstract – 2000. April 2000. Census State Data Center, University of Arkansas at Little Rock. Page 72. The Rand McNally Road Atlas, 2002 Edition. II. Demographic Characteristics Population In 1980, the population of Benton County was 78,155 persons. The county ranked 5th in terms of population among Arkansas’ 75 counties and 3rd behind Washington and Sebastian County among the 16 counties in Northwest Arkansas. By 1990, the population of the county had increased 24.8 percent to 97,499 to rank 4th among Arkansas’ counties and 3rd behind Washington and Sebastian County among the counties in Northwest Arkansas. -

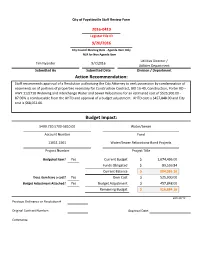

Action Recommendation

City of Fayetteville Staff Review Form 2016-0419 Legistar File ID 9/20/2016 City Council Meeting Date - Agenda Item Only N/A for Non-Agenda Item Utilities Director / Tim Nyander 9/7/2016 Utilities Department Submitted By Submitted Date Division / Department Action Recommendation: Staff recommends approval of a Resolution authorizing the City Attorney to seek possession by condemnation of easements on of portions of properties necessary for Construction Contract, BID 16-49, Construction, Porter RD – HWY 112/71B Widening and Interchange Water and Sewer Relocations for an estimated cost of $525,900.00 - 87.06% is reimbursable from the AHTD and approval of a budget adjustment. AHTD cost is $457,848.00 and City cost is $68,052.00. Budget Impact: 5400.720.5700-5810.00 Water/Sewer Account Number Fund 11011.1501 Water/Sewer Relocations-Bond Projects Project Number Project Title Budgeted Item? Yes Current Budget $ 1,074,496.00 Funds Obligated $ 89,559.84 Current Balance $ 984,936.16 Does item have a cost? Yes Item Cost $ 525,900.00 Budget Adjustment Attached? Yes Budget Adjustment $ 457,848.00 Remaining Budget $ 916,884.16 Must Attach Completed Budget Adjustment! V20140710 Previous Ordinance or Resolution # Original Contract Number: Approval Date: Comments: MEETING OF SEPTEMBER 20, 2016 TO: Mayor Jordan and City Council THRU: Don Marr, Chief of Staff Tim Nyander, Utilities Director Water & Sewer Committee FROM: Jim Beavers, P.E. DATE: September 6, 2016 SUBJECT: Approval of a Resolution authorizing the City Attorney to seek condemnation and orders of possession for water and sewer easements necessary for the City of Fayetteville, Arkansas; Construction Contract, BID 16-49, Construction, Porter RD – HWY 112/71B Widening and Interchange Water and Sewer Relocations for an estimated cost of $525,900.00 and approval of a budget adjustment. -

November 2018 Data Report

August 2012 – November 2018 Data Report Prepared by: Angela Danovi Beaver LakeSmart / StreamSmart Coordinator Ozarks Water Watch 1200 W. Walnut Street, Suite 3405 Rogers, AR 72756 Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................iii Water Quality Parameter Descriptions ............................................................................................................................... iii Alkalinity ......................................................................................................................................................................... iii Conductivity.................................................................................................................................................................... iii pH ................................................................................................................................................................................... iv Total Dissolved Solids ...................................................................................................................................................... v Total Nitrogen ................................................................................................................................................................. v Total Phosphorus ............................................................................................................................................................ -

002.01.20-012P-20015.Pdf

Christian N. Parks James F. Goodhart General Counsel Assistant General Counsel John P. Marks Rob Brown Sr. Assistant General Counsel Assistant General Counsel Phone: 501-223-6327 Fax: 501-223-6463 April 17, 2020 Ms. Jayme Franco Arkansas Secretary of State, Rules & Regulation Filing 500 Woodlane Drive, Room 26 Little Rock, AR 72201 Via email only: [email protected] RE: Legal Notice for Proposed Rules or Regulations – May 2020 meeting Dear Ms. Franco: Attached please find for filing and immediate publication on the Secretary of State’s website the following: Legal Notice for upcoming Commission Meeting to be held on May 21, 2020, which will run in the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette on April 19, 20, and 21, 2020. Yesterday April Soman provided a link to the proposed regulation changes that will be reviewed by the Commission at the upcoming meeting (96 proposals). Please get in touch which her if you have any difficulty accessing the file. Should you have any questions or comments concerning this filing, please do not hesitate to contact me at (501) 223-6327 at your convenience. Sincerely, James F. Goodhart General Counsel Cc: Ms. Barbara Brown, Bureau of Legislative Research [email protected] ARKANSAS REGISTER Proposed Rule Cover Sheet Secretary of State John Thurston 500 Woodlane, Suite 026 Little Rock, Arkansas 72201-1094 (501) 682-5070 www.sos.arkansas.gov Name of Department Legal Division Agency or Division Name Arkansas Game & Fish Commission Other Subdivision or Department, If Applicable Previous Agency Name, If Applicable Contact Person April M. Soman Contact E-mail [email protected] Contact Phone 501-223-6327 Name of Rule 1.00-C Definition of Terms Newspaper Name Arkansas Democrat Gazette Date of Publishing March 22, 23, and 24, 2020 and April 19, 20, and 21, 2020 Final Date for Public Comment May 21, 2020 Location and Time of Public Meeting AGFC Auditorium, 2 Natural Resources Drive, Little Rock AR 72205, at 10:00 a.m. -

2017-18 Arkansas Hunting Guidebook

2017-18 Arkansas Hunting Guidebook Pick up an AGFC conservation license plate at your c=85 m=19 y=0 k=0 c=57 m=80 y=100 k=45 c=20 m=0 y=40 k=6 local revenue office. Learn more atwww.agfc.com. c=15 m=29 y=33 k=0 c=100 m=0 y=91 k=42 c=30 m=0 y=5 k=0 Arkansas Game and Fish Commission Main Office Contact Information 2 Natural Resources Drive • Little Rock, AR 72205 501-223-6300 • 800-364-4263 • www.agfc.com Important Numbers Regional Office Contact Information Stop Poaching Hotline WMD Region 1 • Northeast Office 600-B East Lawson • Jonesboro, AR 72404 Toll-free: 800-482-9262 Toll-free: 877-972-5438 #TIP (#847) for AT&T users (charges apply) 24 hours a day, 7 days a week WMD Region 2 • East Central Office Text a Tip (TIP411) 1201 North Highway 49 • Brinkley, AR 72021 Toll-free: 877-734-4581 Text AGFC and your tip to TIP411 (847411) Texts are completely anonymous WMD Region 3 • Southeast Office Game Checking 771 Jordan Drive • Monticello, AR 71655 Toll-free: 877-731-5627 Toll-free: 877-367-3559 24 hours a day, 7 days a week WMD Region 4 • South Central Office www.agfc.com 500 Ben Lane • Camden, AR 71701 Wildlife Hotline Toll-free: 877-836-4612 Toll-free: 800-440-1477 WMD Region 5 • Southwest Office Deer, Turkey or Elk Permits 7004 Highway 67 East • Perrytown, AR 71801 Toll-free: 877-777-5580 501-223-6359 (office hours only) WMD Region 6 • Hot Springs Office Boating Education Classes 350 Fish Hatchery Road • Hot Springs, AR 71913 Toll-free: 877-493-6424 (office hours only) Toll-free: 877-525-8606 Triple Trophy Program 501-223-6351 (office hours only) WMD Region 6 • Fort Smith Office 8000 Taylor Ave. -

Minutes.Form

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS BOARD OF TRUSTEES UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS AT LITTLE ROCK DONAGHEY STUDENT CENTER CALVIN R. LEDGETTER JR. ASSEMBLY HALL LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS 1:00 P.M., MARCH 17, 2015 AND 8:30 A.M., MARCH 18, 2015 TRUSTEES PRESENT: Chairman Ben Hyneman; Trustees Jane Rogers; Reynie Rutledge; David Pryor; John Goodson; Stephen A. Broughton, MD; Cliff Gibson; Morril Harriman; and Jim von Gremp. TRUSTEE ABSENT: Mark Waldrip. UNIVERSITY ADMINISTRATORS AND OTHERS PRESENT: System Administration: President Donald R. Bobbitt, Vice President for Agriculture Mark J. Cochran, Vice President for Academic Affairs Michael K. Moore, Vice President for Finance and CFO Barbara Goswick, Vice President for Administration Ann Kemp, Director of Internal Audit Jacob Flournoy, Interim Director of Communications Nate Hinkel, General Counsel Fred Harrison, Assistant to the President Angela Hudson and Associate for Administration Sylvia White. UAF Representatives: Chancellor G. David Gearhart, Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Sharon L. Gaber, Interim Vice Chancellor for Finance and Administration Tim O’Donnell, Vice Chancellor for Advancement Chris Wyrick, and Vice Chancellor for Governmental Relations Randy Massanelli. Board of Trustees Meeting March 17-18, 2015 Page 2 UAMS Representatives: Chancellor Daniel W. Rahn; Dean, College of Medicine Richard Smith; Chief Executive Officer Roxane Townsend; Chief Medical Quality Officer Chris Cargile; Chief Financial Officer Hospital Daniel J. Riley; Vice Chancellor and Chief Financial Officer Bill Bowes; Vice Chancellor Communications and Marketing Leslie Taylor and Professor Ron Robertson, M.D. UALR Representatives: Chancellor Joel E. Anderson, Director Budget and Strategic Initiatives Sandra Robertson, Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost Zulma Toro, and Vice Chancellor for Finance and Administration Bob Adams. -

War Eagle Creek Watershed Drinking Water Source for War Eagle Creek Watershedis One of Seven Subwatersheds in the Beaver Lake Watershed

Northwest Arkansas’ Beaver Lake is the War Eagle Creek Watershed drinking water source for War Eagle Creek Watershedis one of seven subwatersheds in the Beaver Lake Watershed. one in eight Beaver Lake Watershed is a part of the White River Watershed. Arkansans. Blackburn Creek Polecat Mountain 23 MADISON CARROLL Pension Mountain Bluff Field Mountain White Hobbs State Park Swain Mountain River Stanley Mountain Beaver Lake Sandstone Mountain Madison County Flower Pot Point Watershed Mississippi Wilderness Management Area River Lookout Samuel Mountain Warm Fork ARKANSAS Kenars Mountain War Eagle Mill 127 BEAVER LAKE Ozark Natural Science Center Bear Hollow Natural Area Piney Creek Clear Creek Best 12 Rockhouse Creek Clifty Creek War Eagle Creek Clifty 23 Madison County Beaver Lake Watershed is a Wilderness Management Area subwatershed of the White River Basin. The White River is a tributary of the Mississippi River. BENTON 45 WAR WASHINGTON 303 EAGLE Pine Creek Nob Hill CREEK Water from War Eagle 21 412 Been Mountain Forum Dry Fork 23S Creek Watershed and other Withrow Springs State Park subwatersheds flows in a Roberts Creek BEAVER LAKE- 303 HINDSVILLE LAKE WHITE RIVER Whitener Branch 412 Alabam northerly direction Hindsville Tater Hill 23 127 Vaughan Mountain into Beaver Lake. War Eagle Creek 412 45 Smyrna Branch Old Berry Branch Keefer Mountain Alabam 412 Horine Mountain Slaven Mountain Goshen Diera Mountain Mill Branch Carlock Mountain Big Onion Creek Boatright Creek Benson Mountain Kings River Dry Creek Bohannan Mountain Mitchell Branch -

An Economic Analysis of Washington County in Northwest Arkansas

AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF WASHINGTON COUNTY IN NORTHWEST ARKANSAS Center for Business and Economic Research Reynolds Center Building 217 Sam M. Walton College of Business 1 University of Arkansas Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701-1201 (479) 575-4151 August 30, 2002 An Economic Analysis of Washington County in Northwest Arkansas I. Geographic Description Washington County is comprised of 950 square miles and is located along the Oklahoma- Arkansas border in the physiographic regions of the Springfield Plateau in the northern portion of the county and the Boston Mountains in the southern portion of the county. Figure 1 highlights the counties that comprise the Northwest Arkansas region, as defined by the Arkansas Department of Economic Development. Washington County is shown in red; all other counties in the region are shown in yellow. Figure 1 – Washington County’s Location A small portion of the Ozark National forest is located in extreme northern and southern Washington County. The White River flows north from Madison County through Washington County into Beaver Lake. Sources: United States Census Bureau. State and County QuickFacts. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/05/05143.html Chart 2-5: Physiographic Regions. Arkansas Statistical Abstract – 2000. April 2000. Census State Data Center, University of Arkansas at Little Rock. Page 72. The Rand McNally Road Atlas, 2002 Edition. Page 10. II. Demographic Characteristics Population In 1980, the population of Washington County was 100,494 persons. The county ranked second in terms of population among Arkansas’ 75 counties behind Pulaski County and first among the 16 counties in Northwest Arkansas. By 1990, the population of the county had increased 12.9 percent to 113,409 to rank second among Arkansas’ counties behind Pulaski County and first among the counties in Northwest Arkansas. -

A Eutrophication Model of the White River Basin Above Beaver Reservoir in Northwest Arkansas Robert A

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Technical Reports Arkansas Water Resources Center 1-1-1973 A Eutrophication Model of the White River Basin Above Beaver Reservoir in Northwest Arkansas Robert A. Gearhart University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Dee Mitchell University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Louis Thibodeaux University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Richard Meyers University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/awrctr Part of the Fresh Water Studies Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Gearhart, Robert A.; Mitchell, Dee; Thibodeaux, Louis; and Meyers, Richard. 1973. A Eutrophication Model of the White River Basin Above Beaver Reservoir in Northwest Arkansas. Arkansas Water Resources Center, Fayetteville, AR. PUB015. 109 This Technical Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Arkansas Water Resources Center at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Technical Reports by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A EUTROPHICATION MODEL OF THE WHITE RIVER BASIN ABOVE BEAVER RESERVOIR IN NORTHWEST ARKANSAS by Robert A. Gearheart WATER RESOURCES RESEARCH CENTER Publication No. 15 In Cooperation With ENGINEERING EXPERIMENT STATION Research Report No. 22 UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS FAYETTEVILLE 1973 PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT PROJECT NO.: B-012-ARK AGREEMENT NO.: 14-01-0001-1877 Starting Date: