Agricultural Implements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multi-Tasking Hand Tools by Rita Pelczar

GREENc GARAGE® Multi-Tasking Hand Tools by Rita Pelczar hen I head to the garden, I Besides extracting weeds by their roots, it’s usually take just a couple of great for digging holes for transplants or Wtools with me, so they need bulbs; and it cuts through anything from to be able to perform a variety of tasks twine to the roots of perennials that you and they have to feel comfortable in my want to divide. The six-and-three-quarter- hands when I use them. here are a few inch, hardened stainless steel blade is ser- that fit the bill. rated and engraved with millimeter depth I’ve long been a fan of a handcraft- measurements to help ensure accurate ed tool from Lewiston, Idaho, with the odd name of Hoe-dag (available from hoss Tools (www.hosstools.com). It’s a well-balanced, short-handled hoe featur- Multi-Purpose Hori-Hori Knife planting. Its vinyl carrier has a loop that can be attached to a belt to keep it safely sheathed until ready for use. The 10-and-a-half-inch-long Handy Weeder Tool, also from Gardener’s edge, is small and light enough to carry on your belt. The five-inch-long, flat beveled blade is handy for weeding in tight places—between young vegetables or flowers, even in planters—easily cut- ting young weeds at their roots without 2-Tine Cultivator Hand Eye Hoe disturbing nearby plants. It also makes precise furrows for sowing seeds. Crafted in Germany, the 2-Tine Cultivator Hand Eye Hoe, available from Garden Tool Company (www. -

Tools and Equipment Ames® Long Fiberglass Handle Shovel Tempered Steel Blade Shovel with Oversized Cushion Grip on a Fiberglass Handle for Added Comfort

Tools and Equipment Ames® Long Fiberglass Handle Shovel Tempered steel blade shovel with oversized cushion grip on a fiberglass handle for added comfort. A heavy-use tool for frequent jobs and yard maintenance. Suitable for transferring all materials such as dirt, mulch, or gravel. Great value to homeowners with any landscaping and gardening requirements. Digging Tools Square Point - 9.75in L x 5in W x 61.25in H AME25337100-2504 UPC 049206634084 Ames® D-Grip Wood Handle Digging Shovel Min. Buy 6EA Retail $34.39 Make that next gardening project a little Round Point - 8.75in L × 4.8in W x 61in H easier with an ergonomic D-grip that provides AME25332100-2504 UPC 049206634008 comfortable hand placement to grab tool. Min. Buy 6EA Retail $34.39 Durable and dependable, built with Ames heritage quality. Features tempered steel blades Tools & Equipment Tools and North American hardwood handle for strength and durability. 8.75in L × 5.5in W x 42.25in H Ames® Long Handle Round Point Floral Shovel The Ames floral tool line is the perfect size and AME2535800-2270 UPC 049206644755 weight for working in the garden. Ideal for Min. Buy 6EA Retail $31.29 raised bed gardening. The tempered steel blade with power collar will dig in any soil condition. It has a North American hardwood handle for Ames® D-Grip Wood Handle Drain Spade strength and durability with a comfort grip and a Ergonomic D-grip that provides comfortable hand convenient hole for hanging. placement. North American hardwood handle for strength and durability. Designed for digging 2in L x 6in W x 52.875in H narrow trenches and cleaning out previously dug AME2916100-1891 UPC 049206633957 ditches. -

Market Farm Tools and Systems

GROWING A NEW GENERATION OF ILLINOIS FRUIT AND VEGETABLE FARMERS MARKET FARM TOOLS AND SYSTEMS Zachary Grant Bill Shoemaker Adapted from John Hendrickson April 2015 Objectives: • Capitalizing a Market Farm • Capitalization Priorities • The Front End of the Market Farm • The Middle of the Market Farm • The Back End of the Market Farm • Concluding Thoughts and Questions Estimated Equipment Needs for Various Sizes of Vegetable Farms. Power Source and Direct Production Postharvest Seed Starting Tillage Seeding Equipment Cultivation Harvesting Handling Delivery rototiller Field small hoop Earth- Wheel hoe, or Back-pack knives, Bulk tank, Pickup house, grow way hand hoes, 1-3 walking sprayer, hand canopy, with lights, seeder, digging acres tractor, irrigation, boxes, packing topper planting Cyclone forks, custom tools buckets, containers or van trays seeder spades work carts 35-40 hp 1000 sq. ft. tractor, Potato 1-row greenhouse, with Cultivat- digger, Roller track transplant cold frames, creeper Planet ing tractor bed lifter, conveyor, 4-6 er, Cargo field gear, Jr. plate (IH Super wagon, hand carts, acres irrigation, van tunnels, power seeder A or IH more walk-in more planting steering, 140) boxes, cooler tools trays high buckets clearance Market Gardening: A Start-up Guide https://attra.ncat.org/attra-pub/summaries/summary.php?pub=18 Table 2. Estimated Equipment Needs for Various Sizes of Vegetable Farms. P r o d u c t i o Po n w D S er ir E e So ec q H Po e ur t u C ar sth d ce S i ul v arv S St an e p ti e est D c ar d e m v st Ha el a -

Redesigning Agricultural Hand Tools in Western Kenya WYCHE, OLSON, KARANU

Redesigning Agricultural Hand Tools in Western Kenya WYCHE, OLSON, KARANU Research Article Redesigning Agricultural Hand Tools in Western Kenya: Considering Human-Centered Design in ICTD Susan Wyche Jennifer Olson Michigan State University, USA Mary Karanu Rural Outreach Africa, Kenya Abstract Human-centered design (HCD) is a creative approach to technology design that prioritizes users’ needs in the design process. It is characterized by three phases: understanding, ideation, and evaluation. Enthusiasm for using HCD per- sists among ICTD (information and communication technologies for development) researchers; funding agencies continue to support efforts to use the approach in development projects. However, published studies documenting each phase of the approach are few. Here, we present one such case study that documents our use of HCD to under- stand farmers’ hand tools in Kenya and to explore their ideas for new tools—designed to make weeding easier. We also present an evaluation of three redesigned tools, which were manufactured by jua kali (local metal workers). Our ªndings suggest that HCD resulted in improved tools. These ªndings motivate a discussion that elaborates on using HCD in ICTD. We suggest that the most signiªcant impacts of HCD may come from using the approach to under- stand diverse local conditions as they relate to design, and from jua kali integrating the approach into their design practices. Finally, we consider how HCD supports (and challenges) conducting ethical research. Keywords: agriculture, design thinking, human-centered design, HCI4D, jua kali, Kenya Introduction Over the last 15 years, there has been signiªcant enthusiasm among researchers, practitioners, and funding agencies for using a Human-Centered Design (HCD) approach to guide the development of technological solu- tions for socioeconomic problems in the developing world (Bazzano, Martin, Hicks, Faughnan, & Murphy, 2017; Gordon, Kramer, Moore, Yeung, & Agogino, 2017). -

Kisankrafttm Operation Manual

TM POST HOLE DIGGER KisanKraft EQ9800 Operation Manual KisanKraft Machine Tools Pvt. Ltd. Sri Huchhanna Tower, #4,1st Main,7-A Cross, Maruthi Layout, Dasarahalli, HAF Post, Hebbal, Bangalore 560024,Karnataka,INDIA ♦ Bangalore (HO) ♦ Ahmedabad ♦ Bhopal ♦ Bhubaneswar ♦ Coimbatore ♦ ♦ Ernakulam ♦ Guwahati ♦ Shimla ♦ Hinudpur ♦ Hubli ♦ Hyderabad ♦ ♦ Jaipur ♦ Karnal ♦ Kolkata ♦ Lucknow ♦ Nagpur ♦ Patna ♦ Pune ♦ Raipur : www.kisankraft.com : [email protected] : +91.80. 22178200 Page 1of 20 TM POST HOLE DIGGER KisanKraft EQ9800 CONTENTS BEFORE GETTING STARTED ......................................................................................... 3 SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS ................................................................................................ 3 OPERATION .................................................................................................................... 6 STARTING AND STOPPING THE ENGINE ..................................................................... 7 TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS ..................................................................................... 11 MAINTENANCE AND STORAGE ................................................................................... 11 SERVICE AND REPAIR ................................................................................................. 16 TROUBLESHOOTING .................................................................................................... 17 : www.kisankraft.com : [email protected] : +91.80. 22178200 Page 2of 20 TM POST HOLE DIGGER -

Tool Inventory

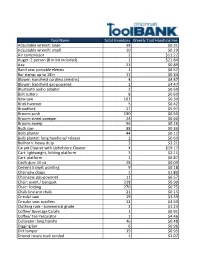

Tool Name Total Inventory Weekly Tool Handling Fee Adjustable wrench: large 38 $0.31 Adjustable wrench: small 10 $0.29 Air compressor 2 $11.22 Auger: 2 person (8 in bit included) 1 $21.84 Axe 23 $0.89 Band saw: portable electric 1 $6.57 Bar clamp: up to 18in 12 $0.34 Blower: handheld cordless (electric) 4 $4.47 Blower: handheld gas-powered 1 $4.47 Bluetooth audio adapter 2 $0.69 Bolt cutters 8 $0.60 Bow saw 103 $0.30 Brick hammer 5 $0.42 Broadfork 17 $5.97 Broom: push 190 $0.50 Broom: street sweeper 24 $0.60 Broom: sweep 96 $0.26 Buck saw 38 $0.33 Bulb planter 44 $0.12 Bulb planter: long handle w/ release 2 $0.69 Bullhorn: heavy duty 3 $3.21 Carpet Cleaner with Upholstery Cleaner 4 $19.17 Cart: lightweight, folding platform 3 $2.11 Cart: platform 1 $6.87 Caulk gun: 10 oz 28 $0.09 Cement trowel: pointing 9 $0.18 Chainsaw chaps 2 $1.80 Chainsaw: gas-powered 11 $6.57 Chair: event / banquet 228 $0.90 Chair: folding 276 $0.75 Chalk line and chalk 21 $0.15 Circular saw 19 $3.39 Circular saw: cordless 12 $4.50 Clothing rack - commercial grade 2 $1.23 Coffee/ Beverage Carafe 1 $0.91 Coffee/ Tea Percolator 1 $4.46 Cultivator: long handle 46 $0.48 Digging bar 6 $0.96 Dirt tamper 35 $0.95 Dremel rotary tool: corded 1 $2.07 Drill: corded 3/8 in chuck 33 $1.50 Drill: cordless 70 $5.25 Drill: drywall screwgun (corded) 1 $2.37 Drywall square: 48 in 6 $0.36 Dust pan 126 $0.14 Ear mufflers 37 $0.30 Easel: folding tripod 18 $0.66 Edger: manual 6 $0.51 Edger: rotary 4 $0.90 Extension cord: 25 ft 8 $0.57 Extension cord: 50 ft 30 $0.75 Extension cord: 100 -

2. Yard Work & Gardening

Chapter 3: Yard Work & Gardening Yard work and gardening may be your hobby, your passion or simply weekend chores. It can be a great source of relaxation &therapy for your mind and body when done with ergonomics in mind. 4 hours in the garden can pose more ergonomic stress to your body than a full work week… Back aches from bending at the waist to plant, clear brush or lift bags of soil Tingling hands from prolonged grasping and squeezing of pruning sheers Sore and irritated elbows from hacking away brush and weeds with a trimmer Loss of grip strength or hand function after using a vibrating weed whacker all day Are your joints withering while your lawn and garden are flourishing? Consider cultivating some good ergonomics techniques so you can enjoy those yard and garden activities and the out-of-doors well into the future. 1 Yard Work and Ergonomic Risks The Ergonomic Risk Factors that contribute to musculoskeletal problems… Excessive or prolonged forward trunk bending to work at ground level Awkward hand/wrist postures due to tool handle size, shape or design Forceful lifting, carrying and placing of heavy loads Overhead use of arms and shoulders working on trees and tall shrubs High impact forceful motions when digging, picking or tilling Squatting and kneeling on knee joints Vibration from power tools such as mowers, weed whackers or clippers 2 Ergonomic Risks ? …not for the garden snail Kneeling, squatting and bending wouldn’t be such a problem if you were like one of those pesky garden snails… spineless invertebrate that can effortlessly conform to any posture or position. -

Adopt-A-Trail Handbook

Town of Reading Adopt-A-Trail Program Handbook What is the Adopt-A-Trail Program? The Town of Reading’s Adopt-A-Trail Program is a volunteer program providing opportunities for members of the community to assist conservation area staff by monitoring, maintaining and enhancing trails and trailhead facilities. Who can adopt a trail? School and youth groups, scout troops, church, community and service organizations, businesses, families, individuals or groups of individuals can adopt a trail. Anyone with an interest in trails and the outdoors is welcome to help preserve our land and provide safe, enjoyable access to the outdoors. What can volunteers do? Adopt-A-Trail volunteers assist Conservation Area staff in managing and maintaining trail systems. Activities include keeping the trail surface free of sticks, rocks and other debris, pruning small limbs from the trail corridor, cleaning waterbars and drainage ditches, and clearing debris from bridges, stairs, and viewing decks. Other responsibilities include litter clean-up, maintaining the trailhead area including parking lot, bulletin board and trail signs, and reporting vandalism, trail hazards or safety issues. Why should you participate? Adopting a trail provides an opportunity for you to be actively involved in conservation. Helping to maintain and enhance existing trails improves the resource for all to enjoy. The effort brings trail and nature enthusiasts closer to the environment and their community. Enjoy the time outdoors and personal satisfaction gained through volunteering on a conservation trail. How to get started: If you have a specific Conservation Area or trail in mind, let us know. If the trail you choose is available for adoption, we'll get you set up right away. -

Garden Tool Binder

Circulating Tools Tools will circulate for one week You can place a hold on a tool All tools will be checked for cleanliness and good condition. You may be charged for any missing or damaged items Tools can NOT be returned to other libraries or in the book drop If you have any questions, please ask the library staff. Thank you! GPL TOOL SHED BORROWING POLICY BASICS 1. Tools may be borrowed for up to seven (7) days. 2. A maximum of three (3) tools may be borrowed at one time. 3. Tools must be returned clean and in good working condition, with all parts and components in their original library package. 4. Tools must be returned inside the Georgetown Peabody Library at the circulation desk during regular hours of operation. 5. Tools must be returned to the circulation desk no later than fifteen (15) minutes before closing time on their due date. 6. Only the borrower is authorized to use the tools. No other persons are permitted to use the tools. 7. The borrower must certify that they are capable of using the tool in a safe and proper manner and will use the tool in a safe and proper manner. 8. The borrower is solely responsible for any loss or damage to a tool while in their possession. 9. The borrower will pay full repair and/or replacement costs should the borrowed tool be stolen, lost, not returned, or damaged. 10.Georgetown Peabody Library staff can refuse to loan any tool to any borrower, or to suspend the borrowing privileges of any borrower for any reason, including but not limited to any perceived violation of the Borrowing Policy. -

THESIS Submitted in P

DESIGN AND DEVELOPEMNT OF A MULTIPURPOSE TOOL CARRIER FOR HOMESTEAD AGRICULTURE By ARYA K.T. (2017-18-006) THESIS Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree Master of Technology In Agricultural Engineering (Farm Power and Machinery) Faculty of Agricultural Engineering and Technology Kerala Agricultural University DEPARTMENT OF FARM MACHINERY AND POWER ENGINEERING KELAPPAJI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY, TAVANUR – 679573 KERALA, INDIA 2019 DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF A MULTIPURPOSE TOOL CARRIER FOR HOMESTEAD AGRICULTURE By ARYA K.T. (2017-18-006) DEPARTMENT OF FARM MACHINERY AND POWER ENGINEERING KELAPPAJI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY, TAVANUR – 679573 KERALA, INDIA 2019 DECLARATION I, hereby declare that this thesis entitled “DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF A MULTIPURPOSE TOOL CARRIER FOR HOMESTEAD AGRICULTURE” is a bonafide record of research work done by me during the course of research and the thesis has not previously formed the basis for the award to me of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship or other similar title, of any other University or Society. Place: Tavanur ARYA K.T. (2017-18-006) Date: CERTIFICATE Certified that this thesis entitled “DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF A MULTIPURPOSE TOOL CARRIER FOR HOMESTEAD AGRICULTURE” is a bonafide record of research work done independently by Ms. Arya K.T. under my guidance and supervision and that it has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma, fellowship or associateship to her. Place: Tavanur Dr. Shaji James P. Date: (Major Advisor, Advisory Committee) Professor, ARS, Mannuthy CERTIFICATE We, the undersigned members of the advisory committee of Ms. ARYA K.T. -

Fiskars Garden Tool Catalogue 2017

The garden catalogue 2017 Fiskars the garden catalogue 12 10 32 14 39 42 51 47 25 4 James Wong in partnership Grass shears 54 Children’s Tools with Fiskars Servo-System™ Weed pullers Please note! All the measurements 6 New products & innovations Xact™ · Light portrayed in the catalogue are packaging Reel Mowers measurements. 8 Wood Preparation StaySharp™ Axes · Handling and preparation tools · Saws 39 Plant Care 18 Soil Care Scissors Shovels, spades & forks Pruners Xact™ · Light™ · Solid™ PowerGear™ · SmartFit™ · Soil care tools SingleStep™ · Quantum™ · Light · Solid™ Inspiration™ Nursery tools Loppers Over 365 years of history are proof of our Premium Planters™ · Solid™ · PowerGear X™ · PowerGear™ · Inspiration™ SmartFit™ · SingleStep™ commitment to quality. Fiskars products are Hedge shears ingeniously functional, uniquely user-friendly, 32 Lawn Care PowerGear X™ · PowerGear™ · Rakes SmartFit™ · SingleStep™ · impressively long-lasting and aesthetically iconic. Light · Solid™ Quantum™ Tree pruners Accessories James Wong Gardening tips from James Wong in partnership with Fiskars 1. Pruning Almost anything that grows benefits from pruning. We didn’t have to think too hard about who should be the Want supersweet apples? A light pruning of face of our award-winning garden hand tool range in the UK. fruit trees in summer lets in more light to the developing crop. Trials have shown that this can TV presenter, ethnobotanist and best-selling author James make them measurably sweeter, double their Wong ticked all the right boxes. After all, we are not your antioxidant content and intensify their colour. average garden tool company…we don’t make old-fashioned Twice the nutrition for five mins of snipping. -

Looking After Your Tools Spade, Fork, Rake, Hoes, Trowel, Dibber, Garden

Looking after your tools Spade, fork, rake, hoes, trowel, dibber, garden line secateurs, hosepipe and watering can, shears and slasher: What could be simpler? Clean, dry or lightly oiled, sharp, properly kept, the right ones for the job, your tools are your best laboursaving friends! Dibbers make ideal holes for your planting out, and pushed beside the plant then fill the hole and firm it in nicely. Storage Gloves can be hung up to dry with pegs on a short clothes line, boots put upside down on two short stakes or hung through a horizontal ladder. Bow- saws should be hung vertically (release the tension). Spades and forks can be hung vertically from a rack (made from an old pallet) so that they dry; sledge hammers, axes, slashers, bill hooks, pitchforks and hoes (perhaps handle downwards) can join them, or hang on the wall. Lightly oil them and protect the blades. Small tools like hammers, pliers, secateurs, trowels, hand forks, scoops, onion hoes, weed augurs etc. are best oiled and hung up - perhaps in open spring-clips screwed to a batten. It is a matter of space and opportunity. Ropes should be coiled - put a half twist in each hawser loop in the same direction as you are coiling it to prevent kinking up. Hosepipes can be coiled and hung on brackets if they do not come with their own reel. Sharpening stones: these are fragile - flat stones, cigar and canoe stones are best stored safely in boxes with padding to steady them. Flat stones need a board with end stops to hold them while in use.