SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES on the GRADUATE VOICE RECITAL of JEREMY SIMMONS Jeremy L.B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francesco Cavalli One Man. Two Women. Three Times the Trouble

GIASONE FRANCESCO CAVALLI ONE MAN. TWO WOMEN. THREE TIMES THE TROUBLE. 1 Pinchgut - Giasone Si.indd 1 26/11/13 1:10 PM GIASONE MUSIC Francesco Cavalli LIBRETTO Giacinto Andrea Cicognini CAST Giasone David Hansen Medea Celeste Lazarenko Isiile ORLANDO Miriam Allan Demo BY GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL Christopher Saunders IN ASSOCIATION WITH GLIMMERGLASS FESTIVAL, NEW YORK Oreste David Greco Egeo Andrew Goodwin JULIA LEZHNEVA Delfa Adrian McEniery WITH THE TASMANIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Ercole Nicholas Dinopoulos Alinda Alexandra Oomens XAVIER SABATA Argonauts Chris Childs-Maidment, Nicholas Gell, David Herrero, WITH ORCHESTRA OF THE ANTIPODES William Koutsoukis, Harold Lander TOWN HALL SERIES Orchestra of the Antipodes CONDUCTOR Erin Helyard CLASS OF TIMO-VEIKKO VALVE DIRECTOR Chas Rader-Shieber LATITUDE 37 DESIGNERS Chas Rader-Shieber & Katren Wood DUELLING HARPSICHORDS ’ LIGHTING DESIGNER Bernie Tan-Hayes 85 SMARO GREGORIADOU ENSEMBLE HB 5, 7, 8 and 9 December 2013 AND City Recital Hall Angel Place There will be one interval of 20 minutes at the conclusion of Part 1. FIVE RECITALS OF BAROQUE MUSIC The performance will inish at approximately 10.10 pm on 5x5 x 5@ 5 FIVE TASMANIAN SOLOISTS AND ENSEMBLES Thursday, Saturday and Monday, and at 7.40 pm on Sunday. FIVE DOLLARS A TICKET AT THE DOOR Giasone was irst performed at the Teatro San Cassiano in Venice FIVE PM MONDAY TO FRIDAY on 5 January 1649. Giasone is being recorded live for CD release on the Pinchgut LIVE label, and is being broadcast on ABC Classic FM on Sunday 8 December at 7 pm. Any microphones you observe are for recording and not ampliication. -

ARSC Journal

HISTORIC VOCAL RECORDINGS STARS OF THE VIENNA OPERA (1946-1953): MOZART: Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail--Wer ein Liebchen hat gafunden. Ludwig Weber, basso (Felix Prohaska, conductor) ••.• Konstanze ••• 0 wie angstlich; Wenn der Freude. Walther Ludwig, tenor (Wilhelm Loibner) •••• 0, wie will ich triumphieren. Weber (Prohaska). Nozze di Figaro--Non piu andrai. Erich Kunz, baritone (Herbert von Karajan) •••• Voi che sapete. Irmgard Seefried, soprano (Karajan) •••• Dove sono. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, soprano (Karajan) . ..• Sull'aria. Schwarzkopf, Seefried (Karajan). .• Deh vieni, non tardar. Seefried (Karajan). Don Giovanni--Madamina, il catalogo e questo. Kunz (Otto Ackermann) •••• Laci darem la mano. Seefried, Kunz (Karajan) • ••• Dalla sua pace. Richard Tauber, tenor (Walter Goehr) •••• Batti, batti, o bel Masetto. Seefried (Karajan) •.•• Il mio tesoro. Tauber (Goehr) •••• Non mi dir. Maria Cebotari, soprano (Karajan). Zauberfl.Ote- Der Vogelfanger bin ich ja. Kunz (Karajan) •••• Dies Bildnis ist be zaubernd schon. Anton Dermota, tenor (Karajan) •••• 0 zittre nicht; Der Holle Rache. Wilma Lipp, soprano (Wilhelm Furtwangler). Ein Miidchen oder Weibchen. Kunz (Rudolf Moralt). BEETHOVEN: Fidelio--Ach war' ich schon. Sena Jurinac, soprano (Furtwangler) •••• Mir ist so wunderbar. Martha Modl, soprano; Jurinac; Rudolf Schock, tenor; Gottlob Frick, basso (Furtwangler) •••• Hat man nicht. Weber (Prohaska). WEBER: Freischutz--Hier im ird'schen Jammertal; Schweig! Schweig! Weber (Prohaska). NICOLAI: Die lustigen Weiher von Windsor--Nun eilt herbei. Cebotari {Prohaska). WAGNER: Meistersinger--Und doch, 'swill halt nicht gehn; Doch eines Abends spat. Hans Hotter, baritone (Meinhard von Zallinger). Die Walkilre--Leb' wohl. Hotter (Zallinger). Gotterdammerung --Hier sitz' ich. Weber (Moralt). SMETANA: Die verkaufte Braut--Wie fremd und tot. Hilde Konetzni, soprano (Karajan). J. STRAUSS: Zigeuner baron--0 habet acht. -

Lucio Silla Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart S T a G I O N E D I O P E R a 2 0 1 4 / 2 0 1

6 W L u o c l i f o g a S n i l g l a A m a d e u s M o z a r t Lucio Silla Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart S t a g i o n e d i O p e r a 2 0 1 4 / 2 0 1 5 Stagione di Opera 2014 / 2015 Lucio Silla Dramma in musica in tre atti Libretto di Giovanni De Gamerra Musica di Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Nuova produzione In coproduzione con Mozartwoche Salzburg/Fondazione Mozarteum e Festival di Salisburgo EDIZIONI DEL TEATRO ALLA SCALA TEATRO ALLA SCALA PRIMA RAPPRESENTAZIONE Giovedì 26 febbraio 2015, ore 20 - Turno E REPLICHE febbraio Sabato 28 Ore 20 – Turno D marzo Martedì 3 Ore 20 – ScalAperta Giovedì 12 Ore 20 – Turno B Sabato 14 Ore 20 – Turno A Martedì 17 Ore 20 – Turno C SOMMARIO 4 Lucio Silla . Il libretto 28 Il soggetto Argument – Synopsis – Die Handlung – ࠶ࡽࡍࡌ – Сюжет Cesare Fertonani 40 L’opera in breve Cesare Fertonani 42 La musica Giancarlo Landini 45 Luci del crepuscolo Il Lucio Silla di Mozart per Milano Raffaele Mellace 79 Modernità in veste storica Marc Minkowski parla di Mozart e di Lucio Silla 85 Wolfgang A. Mozart - Lucio Silla Ronny Dietrich 104 Lucio Silla alla Scala Luca Chierici 113 Marc Minkowski 115 Marshall Pynkoski 116 Antoine Fontaine 117 Jeannette Lajeunesse Zingg 118 Hervé Gary 119 Lucio Silla . I personaggi e gli interpreti 121 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Cesare Fertonani Cronologia della vita e delle opere 128 Letture Cesare Fertonani 130 Ascolti Luigi Bellingardi 133 Coro del Teatro alla Scala 134 Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala 135 Corpo di Ballo del Teatro alla Scala 136 Teatro alla Scala Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart . -

Showstoppers! Soprano

LIGHT OPERA SHOWSTOPPERS – SHOWSTOPPERS! The list below is a guide to arias from the realm of light opera that are bound to get attention, as they require not only exquisite singing, but also provide opportunities for acting, so necessary in the HAROLD HAUGH LIGHT OPERA VOCAL COMPETITION. Some, although from serious works, are light in nature, and are included. The links below the title, go to performances on YouTube, so you can audition the song. An asterisk (*) indicates the Guild has the score in English. SOPRANO ENGLISH Poor Wand’ring One – Pirates of Penzance (Gilbert and Sullivan)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5QRnwT2EYD8 The Hours Creep On Apace - HMS Pinafore (Gilbert and Sullivan)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lGMnr7tPKKU The Moon and I – The Mikado (Gilbert and Sullivan)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EcNtTm5XEfY I Built Upon a Rock – Princess Ida (Gilbert and Sullivan)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aF_MHyXPui8 I Live, I Breathe – Ages Ago (Gilbert and Clay)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-HalKwnNd8 Light As Thistledown – Rosina (Shield) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9yrQ2boAb50 When William at Eve – Rosina (Shield) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Vc50GGV_SA I Dreamt I Dwelt In Marble Halls – Bohemian Girl (Balfe)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IoM1hYqpRSI At Last I’m Sovereign Here – The Rose Of Castile (Balfe)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hswFzeqY8PY Hark the Ech’ing Air – The Fairy Queen (Purcell)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NeQMxI1S84U VIENNESE Meine Lippen Sie Kussen So Heiss – Giuditta (Lehar) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p_kaOYC_Fww -

Don Giovanni Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards

Opera Box 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards. See the Unit Overview for a detailed explanation. Before returning the box, please fill out the Evaluation Form at the end of the Teacher’s Guide. As this project is new, your feedback is imperative. Comments and ideas from you – the educators who actually use it – will help shape the content for future boxes. In addition, you are encouraged to include any original lesson plans. The Teacher’s Guide is intended to be a living reference book that will provide inspiration for other teachers. If you feel comfortable, include a name and number for future contact from teachers who might have questions regarding your lessons and to give credit for your original ideas. You may leave lesson plans in the Opera Box or mail them in separately. Before returning, please double check that everything has been assembled. The deposit money will be held until I personally check that everything has been returned (i.e. CDs having been put back in the cases). -

Don Giovanni Synopsis 5

Table of Contents An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials 3 Production Information/Meet the Characters 4 The Story of Don Giovanni Synopsis 5 The History of Mozart’s Don Giovanni 8 Guided Listening Notte e giorno faticar 11 Ah! Chi mi dice mai 13 Là ci darem la mano 14 Batti, batti, o bel Masetto 15 Metà di voi qua vadano 16 Sola, sola, in buio loco 17 Il mio tesoro intanto 18 Non mi dir, bell’idol mio 19 Don Giovanni Resources About the Composer 20 Online Resources 22 Additional Resources Reflections after the Opera 23 The Emergence of Opera 24 A Guide to Voice Parts and Families of the Orchestra 28 Glossary 29 References Works Consulted 33 2 An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials The goal of Pathways for Understanding materials is to provide multiple “pathways” for learning about a specific opera as well as the operatic art form, and to allow teachers to create lessons that work best for their particular teaching style, subject area, and class of students. Meet the Characters / The Story/ Resources Fostering familiarity with specific operas as well as the operatic art form, these sections describe characters and story, and provide historical context. Guiding questions are included to suggest connections to other subject areas, encourage higher-order thinking, and promote a broader understanding of the opera and its potential significance to other areas of learning. Guided Listening The Guided Listening section highlights key musical moments from the opera and provides areas of focus for listening to each musical excerpt. -

Migrating Mozart, Or Life As a Substitute Aria in the Eighteenth Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt am Main Migrating Mozart, or Life as a Substitute Aria in the Eighteenth Century ISABELLE EMERSON Hikers, especially in difficult terrain, spend a lot of time looking down at the trail where, among the frequent sights, are deposits by various animals. These droppings, or scat, are packed with information about the local fauna. But they are also a significant factor in the distribution of flora, as animals and birds eat in one location and eliminate in another—a process of dissemination botanists term seed dispersal. The practice in the eighteenth century, of carrying one’s favorite arias around from opera to opera, strikes me as quite similar to this paradigm in nature: the singer ingests the aria in one location, and emits it in another. The result is significantly similar: the dispersal of the material over the geographical range of the carrier. * There has been a tendency to regard the substitute aria as not very welcome baggage, and to assess this practice and its near relative, the pastiche, as not quite respectable. I suggest that we look at the practice, not as detracting from the merits of its host work, but as a means of distribution of music. In the case of Mozart’s presence in London, this may be of some importance since none of his operas was staged in that city until 1806 (La clemenza di Tito)—fifteen years after his death. By that time, however, quite a bit of his operatic music, and many of his instrumental works, had been heard in London. -

Reviewof Formalfunctionsinperspective

Intégral 31 (2017) pp. 97–126 Review of Formal Functions in Perspective, edited by Steven Vande Moortele, Julie Pedneault-Deslauriers, and Nathan John Martin by Graham G. Hunt ne of several major collections of analytical es- This essay is divided into two main sections, the first O says released over the past year or so,1 Formal Func- summarizing and reflecting on the essays, and the second tions in Perspective represents a first of its kind in two ways. taking the analytical baton from one essay and extending On the one hand, it is the inaugural collection of articles it into new case studies. In doing so, I hope to not only pro- employing William Caplin’s resuscitated and refined For- vide a general critical commentary on the book standard to menlehre approach, “Formal Functions”; but on the other, a review of this kind, but also to demonstrate the potential it is the first Festschrift-style tribute to William Caplin, one “lineage” of future work that can spring from these well- of the pre-eminent scholars in our midst, who is well- written and thought-provoking essays. deserving of such a collection of essays in his style and in his honor. The volume boasts such an impressive array of scholars, repertoires, and diversity of approaches that it 1. The Articles proves not only the “usefulness” of Formal-Function the- 1.1 Theoretical Studies in Haydn and Mozart ory2 but provides a taste of its untapped utility in reper- Poundie Burstein opens the proceedings with “Func- toires outside of the Classical canon (for example, Schu- mann and Schoenberg), and in tandem with other an- tial Formanality” in Haydn—a play on words reminiscent alytical methods such as hermeneutic analysis and dra- of the opening to his 2005 article on the auxiliary cadence, maturgical/textual interpretation. -

An Examination of the Role of the Tenor in Mozart's Operas

HINSON, DANIEL ROSS, D.M.A. Are You Serious? An Examination of the Role of the Tenor in Mozart’s Operas Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte. (2009) Directed by Dr. Carla LeFevre. 59 pp. Two tenor roles in Mozart’s late Italian operas, Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni and Ferrando in Così fan tutte , do not precisely fit the musical or dramatic expectations of either opera seria or opera buffa . Although Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte are considered exemplars of the opera buffa style, Mozart and his librettist, da Ponte, use music and text that resemble the antiquated style of opera seria to characterize these tenors. This dichotomy helps to define Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte as drammi giocosi , a hybrid operatic genre that mixes elements of opera seria and opera buffa , and features interactions between three distinct strata of characters: high ( parti serie ), middle (di mezzo carattere ) and low ( parti buffi ). An examination of the late-eighteenth century decline of opera seria , and with it the gradual disappearance of the castrato from the operatic stage, is contrasted with the rise of opera buffa and the eventual ascendancy of the tenor as romantic protagonist. The connections between opera buffa and the commedia dell’arte tradition are examined with particular attention to the character types in Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte . Analysis of the arias from both tenor roles, especially with regard to musical form, tonality, and versification, confirms Don Ottavio and Ferrando as parti serie , and not pure parody of the opera seria style. -

Table of Contents

Don Giovanni By Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart STUDY GUIDE 2018-2019 SEASON Please join us in thanking the generous sponsors of the Education and Outreach Activities of Virginia Opera: Alexandria Commission for the Arts ARTSFAIRFAX Chesapeake Fine Arts Commission Chesterfield County City of Norfolk CultureWorks Dominion Energy Franklin-Southampton Charities Fredericksburg Festival for the Performing Arts Herndon Foundation Henrico Education Fund National Endowment for the Arts Newport News Arts Commission Northern Piedmont Community Foundation Portsmouth Museum and Fine Arts Commission R.E.B. Foundation Richard S. Reynolds Foundation Suffolk Fine Arts Commission Virginia Beach Arts & Humanities Commission Virginia Commission for the Arts Wells Fargo Foundation Williamsburg Area Arts Commission York County Arts Commission Virginia Opera extends sincere thanks to the Woodlands Retirement Community (Fairfax, VA) as the inaugural donor to Virginia Opera’s newest funding initiative, Adopt-A-School, by which corporate, foundation, group and individual donors can help share the magic and beauty of live opera with underserved children. For more information, contact Cecelia Schieve at [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Preface………………………………………………………….4 Objectives………………………………………………………5 What is Opera…………………………………………………..6 The Operatic Voice……………………………………………..8 Opera Production……………………………………………….9 About the Composer……………………………...…………….10 Lorenzo da Ponte………………………………………………12 The Don Juan Legend in Literature and Music..........................14 DON GIOVANNI: Comedy or Tragedy……………………….16 Cast of Characters……………………………………………...18 DON GIOVANNI: A Musical Synopsis……………………….19 Vocabulary: Words to Think About……………………………28 Suggestions for Classroom Discussion………………………....29 Discography…………………………………………………….30 3 Preface Purpose This study guide is intended to aid you in increasing your understanding and appreciation of DON GIOVANNI, and if you are an educator or parent, in sharing some of this content with youth. -

WTO 2019 Audition Tour Aria Frequency Data

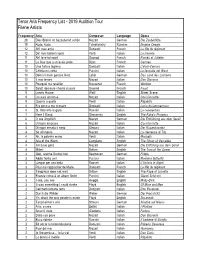

Tenor Aria Frequency List - 2019 Audition Tour Filene Artists Frequency Aria Composer Language Opera 28 Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön Mozart German Die Zauberflöte 19 Kuda, kuda Tchaikovsky Russian Engene Onegin 12 Ah! mes amis Donizetti French La fille du régiment 12 De' miei bollenti spiriti Verdi Italian La traviata 11 Ah! leve-toi soleil Gounod French Roméo et Juliette 11 La fleur que tu m'avais jetée Bizet French Carmen 10 Una furtiva lagrima Donizetti Italian L'elisir d'amore 10 Ch'ella mi creda Puccini Italian La fanciulla del West 10 Dein ist mein ganzes Herz Lehár German Das Land des Lächelns 10 Il mio tesoro Mozart Italian Don Giovanni 10 Pourquoi me reveiller Massenet French Werther 10 Salut! demeure chaste et pure Gounod French Faust 9 Lonely House Weill English Street Scene 9 Un aura amorosa Mozart Italian Cosi fan tutte 9 Questa o quella Verdi Italian Rigoletto 8 Fra poco a me ricovero Donizetti Italian Lucia di Lammermoor 8 Si, ritrovarla io giuro Rossini Italian La cenerentola 7 Here I Stand Stravinsky English The Rake's Progress 6 O wie ängstlich Mozart German Die Entführung aus dem Serail 6 Un'aura amorosa Mozart Italian Cosi fan tutte 5 Di rigori armato il seno Strauss Italian Der Rosenkavalier 4 Se all’impero Mozart Italian La clemenza di Tito 4 Ah, la paterna mano Verdi Italian Macbeth 4 Aria of the Worm Corigliano English The Ghost of Versailles 4 Ich baue ganz Mozart German Die Entfürung aus dem Serail 4 Miles! Britten English The Turn of the Screw 3 Gott, welche Dunkel hier Beethoven German Fidelio 3 Addio fiorito -

DON GIOVANNI Web.Pdf

Foto: Metropolitan opera W. A. Mozart DON GIOVANNI Subota, 29. listopada 2011., 19 sati NOVA PRODUKCIJA! THE MET: LIVE IN HD SERIES IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM ITS FOUNDING SPONZOR Neubauer Family Foundation GLOBAL CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP OF THE MET LIVE IN HD IS PROVIDED BY THE HD BRODCASTS ARE SUPPORTED BY Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart DON GIOVANNI Dramma giocoso u dva ina, K 527 Libreto: Lorenzo da Ponte SUBOTA, 29. LISTOPADA 2011. POČETAK U 19 SATI. Praizvedba: Gräflich Nostitzsches Nationaltheater, Prag, 29. listopada 1787. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Narodno zemaljsko kazalište, Zagreb, 19. siječnja 1875. Prva izvedba u Metropolitanu 28. studenoga 1883. Premijera ove izvedbe u Metropolitanu 13. listopada 2011. DON GIOVANNI Mariusz Kwiecien Zbor i orkestar Metropolitana DONNA ANNA Marina Rebeka ZBOROVOĐA Donald Palumbo DON OTTAVIO Ramón Vargas DIRIGENT Fabio Luisi DONNA ELVIRA Barbara Frittoli REDATELJ Michael Grandage LEPORELLO Luca Pisaroni SCENOGRAF I KOSTIMOGRAF ZERLINA Mojca Erdmann Christopher Oram MASETTO Joshua Bloom OBLIKOVATELJICA RASVJETE Paule Constable KOMTUR Štefan Kocán KOREOGRAF Ben Wright Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: Vaša nada da će se opera iz tragedije razviti u plemenitiji oblik, u novije se vrijeme u najvećoj mjeri ispunila u Don Giovanniju. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe u pismu Friedrichu von Schilleru, 1797. Što je savršenije od svake točke u Don Giovanniju? Gdje je uopće glazba tako bogata i individualna, sposobna da karakterizira s toliko sigurnosti i toliko savršeno i s takvom punoćom obilja kao u tome djelu? Richard Wagner Tekst talijanski Titlovi engleski Stanka poslije prvoga čina. Svršetak oko 22 sata i 35 minuta. Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: PRVI IN upoznajemo tzv.