An Analysis at Three Levels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

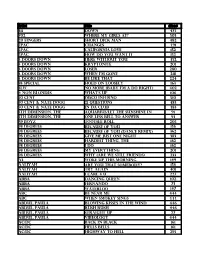

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Partyman by Title

Partyman by Title #1 Crush (SCK) (Musical) Sound Of Music - Garbage - (Musical) Sound Of Music (SF) (I Called Her) Tennessee (PH) (Parody) Unknown (Doo Wop) - Tim Dugger - That Thing (UKN) 007 (Shanty Town) (MRE) Alan Jackson (Who Says) You - Can't Have It All (CB) Desmond Decker & The Aces - Blue Oyster Cult (Don't Fear) The - '03 Bonnie & Clyde (MM) Reaper (DK) Jay-Z & Beyonce - Bon Jovi (You Want To) Make A - '03 Bonnie And Clyde (THM) Memory (THM) Jay-Z Ft. Beyonce Knowles - Bryan Adams (Everything I Do) I - 1 2 3 (TZ) Do It For You (SCK) (Spanish) El Simbolo - Carpenters (They Long To Be) - 1 Thing (THM) Close To You (DK) Amerie - Celine Dion (If There Was) Any - Other Way (SCK) 1, 2 Step (SCK) Cher (This Is) A Song For The - Ciara & Missy Elliott - Lonely (THM) 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) (CB) Clarence 'Frogman' Henry (I - Plain White T's - Don't Know Why) But I Do (MM) 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New (SF) Cutting Crew (I Just) Died In - Coolio - Your Arms (SCK) 1,000 Faces (CB) Dierks Bentley -I Hold On (Ask) - Randy Montana - Dolly Parton- Together You And I - (CB) 1+1 (CB) Elvis Presley (Now & Then) - Beyonce' - There's A Fool Such As I (SF) 10 Days Late (SCK) Elvis Presley (You're So Square) - Third Eye Blind - Baby I Don't Care (SCK) 100 Kilos De Barro (TZ) Gloriana (Kissed You) Good - (Spanish) Enrique Guzman - Night (PH) 100 Years (THM) Human League (Keep Feeling) - Five For Fighting - Fascination (SCK) 100% Pure Love (NT) Johnny Cash (Ghost) Riders In - The Sky (SCK) Crystal Waters - K.D. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Steve Mcdaniel ~ Director on May 22Nd, Our Department Along with Most of Indiana Moved Into Stage 3 of the Governor’S Back on Track Plan

Fort Wayne Parks & Recreation Department Staff Reports May 13, 2020 to June 10, 2020 Steve McDaniel ~ Director On May 22nd, our department along with most of Indiana moved into Stage 3 of the Governor’s Back on Track plan. This stage opened several of our facilities that were closed during stages 1 & 2. To see a complete list, please see the FWPRD’s Back on Track plan. http://www.fortwayneparks.org/images/img/COVID_GRAPH.jpg On May 20th, we cancelled summer camps at both Franke Park and Salomon Farm. Guidelines from the CDC along with research our team has conducted showed that our two camps could not operate in the same capacity that it typically does. It is always our goal to provide quality camp experience and be able to maintain the necessary precautions to keep campers and staff safe. The Marketing team has adjusted the Fun Times with input from all of our program staff showing all of the recreational opportunities that are available this summer. I want to commend the staff for being very versatile and creative in their approaches to providing classes, events, and activities for our community. On May 21st in Governor Holcomb’s Executive Order 20-28, he changed his stance on when playgrounds would open from previous plans. We continue to keep our playgrounds and splash pads closed until he identifies when that directive changes. Additional investigations shows that recommendations from the CDC specifically call out that splash pads should remain closed along with playgrounds. The Theater concert series is the next big decision we have to make this season due to the COVID-19 virus. -

“Smackdown”: a Textual Analysis of Class, Race and Gender in WWE Televised Professional Wrestling

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2012 Ideological “Smackdown”: A Textual Analysis of Class, Race and Gender in WWE Televised Professional Wrestling Casey Brandon Hart University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Hart, Casey Brandon, "Ideological “Smackdown”: A Textual Analysis of Class, Race and Gender in WWE Televised Professional Wrestling" (2012). Dissertations. 550. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/550 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi IDEOLOGICAL “SMACKDOWN”: A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF CLASS, RACE AND GENDER IN WWE TELEVISED PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING by Casey Brandon Hart Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 ABSTRACT IDEOLOGICAL “SMACKDOWN”: A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF CLASS, RACE AND GENDER IN WWE TELEVISED PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING by Casey Brandon Hart May 2012 The focus of this study is an in-depth intertextual examination of how the WWE in 2010 and by extension contemporary professional wrestling in general represents a microcosm of modern cultural ideology. The study examines three major areas in which this occurs. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

AC/DC BONFIRE 01 Jailbreak 02 It's a Long Way to the Top 03 She's Got

AC/DC AEROSMITH BONFIRE PANDORA’S BOX DISC II 01 Toys in the Attic 01 Jailbreak 02 Round and Round 02 It’s a Long Way to the Top 03 Krawhitham 03 She’s Got the Jack 04 You See Me Crying 04 Live Wire 05 Sweet Emotion 05 T.N.T. 06 No More No More 07 Walk This Way 06 Let There Be Rock 08 I Wanna Know Why 07 Problem Child 09 Big 10” Record 08 Rocker 10 Rats in the Cellar 09 Whole Lotta Rosie 11 Last Child 10 What’s Next to the Moon? 12 All Your Love 13 Soul Saver 11 Highway to Hell 14 Nobody’s Fault 12 Girls Got Rhythm 15 Lick and a Promise 13 Walk All Over You 16 Adam’s Apple 14 Shot Down in Flames 17 Draw the Line 15 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 18 Critical Mass 16 Ride On AEROSMITH PANDORA’S BOX DISC III AC/DC 01 Kings and Queens BACK IN BLACK 02 Milk Cow Blues 01 Hells Bells 03 I Live in Connecticut 02 Shoot to Thrill 04 Three Mile Smile 05 Let It Slide 03 What Do You Do For Money Honey? 06 Cheesecake 04 Given the Dog a Bone 07 Bone to Bone (Coney Island White Fish) 05 Let Me Put My Love Into You 08 No Surprize 06 Back in Black 09 Come Together 07 You Shook Me All Night Long 10 Downtown Charlie 11 Sharpshooter 08 Have a Drink On Me 12 Shithouse Shuffle 09 Shake a Leg 13 South Station Blues 10 Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution 14 Riff and Roll 15 Jailbait AEROSMITH 16 Major Barbara 17 Chip Away the Stone PANDORA’S BOX DISC I 18 Helter Skelter 01 When I Needed You 19 Back in the Saddle 02 Make It 03 Movin’ Out AEROSMITH 04 One Way Street PANDORA’S BOX BONUS CD 05 On the Road Again 01 Woman of the World 06 Mama Kin 02 Lord of the Thighs 07 Same Old Song and Dance 03 Sick As a Dog 08 Train ‘Kept a Rollin’ 04 Big Ten Inch 09 Seasons of Wither 05 Kings and Queens 10 Write Me a Letter 06 Remember (Walking in the Sand) 11 Dream On 07 Lightning Strikes 12 Pandora’s Box 08 Let the Music Do the Talking 13 Rattlesnake Shake 09 My Face Your Face 14 Walkin’ the Dog 10 Sheila 15 Lord of the Thighs 11 St. -

Culturehhi Newsletter

CULTUREHHI NEWSLETTER W W W . C U L T U R E H H I . O R G CULTUREHHI NEWSLETTER L o c a l A r t i s t , S o n j a G r i f f i n E v a n s & t h e 4 0 0 Y e a r C o m m e m o r a t i o n Sonja Griffin Evans at work on "The First Family" The 400 Year Commemoration The 400th Anniversary Commemorative Weekend August 23-25 is a multi-day celebration in Hampton, Virginia centered around the First African arrival, including dedication and remembrance ceremonies, gallery exhibits, historical tours, conferences, cultural workshops and music. Congress established the 400 Years of African-American History Commission. For more than two years, the Hampton 2019 Commemoration Commission and Virginia’s, “2019 Commemoration, American Evolution" have sponsored programs that highlight not just the arrival of Africans but also other significant developments in the state’s – and the nation’s – history, including the establishment of the first representative legislative assembly in the New World. CULTUREHHI NEWSLETTER One of the The highlights of the 400 Year Commemoration will be the unveiling of a unique painting entitled, 'The First Family' by international artist Sonja Griffin Evans at the Fort Monroe Visitor and Education Center on Saturday August 24th, 2019 at 2:00 P.M., to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the first Africans to arrive in English North America in 1619. The ship carrying the first enslaved Africans in the New World reached the shores of North America at Point Comfort, now Fort Monroe. -

Jessica Rees [email protected] 760-834-8599

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Jessica Rees [email protected] 760-834-8599 SPOTLIGHT 29 CASINO PROUDLY PRESENTS GRAMMY AWARD-WINNER PETER CETERA Saturday, November 14 at 8 p.m. COACHELLA, CA – (August 18, 2015) – Spotlight 29 Casino is proud to present Grammy Award winning singer and songwriter, Peter Cetera, on Saturday, November 14 at 8 p.m. Tickets are on sale Friday, August 21 at 10 a.m. at www.Spotlight29.com. Spotlight 29 Casino’s Spotlight Showroom offers the premier entertainment experience in the Coachella Valley. From 1968 through 1986, Cetera was the singer, songwriter and bass player for the legendary rock group “Chicago.” In his time with the group, they recorded 18 of the most memorable albums of a generation, including such hits as “If You Leave Me Now,” “Hard to Say I’m Sorry,” “Baby What a Big Surprise,” “You’re the Inspiration,” “Stay the Night,” “Love Me Tomorrow,” “Happy Man,” “Feeling Stronger Every Day” and “Along Comes a Woman.” A solo artist since 1986, Cetera has recorded 10 time-honored CD’s including his #1 hits, the Academy Award nominated song “The Glory of Love” from the hit movie “The Karate Kid II,” “The Next Time I Fall” with Amy Grant, “Feels Like Heaven” with Chaka Kahn, “After All” with Cher from the motion picture “Chances Are,” “No Explanation” from the mega hit film, “Pretty Woman” and the unforgettable “Restless Heart.” Cetera is currently touring with his seven-piece electric band, “The Bad Daddy’s” and still enjoys performing his timeless hits, which continue to touch the lives of so many people worldwide. -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA -

Daily Eastern News: January 22, 1988 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep January 1988 1-22-1988 Daily Eastern News: January 22, 1988 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1988_jan Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: January 22, 1988" (1988). January. 9. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1988_jan/9 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1988 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in January by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOG sets goals for new plan . By MATT HORTENSTINE Staff writer The Board of Governors set up a 17-goal plan to attract and retain minority, female and disabled students at its meeting Thursday at Chicago State University. BOG spokesperson Pam Meyer said the steps taken were in· reaction to a 1985 law that requires the Illinois Board of Higher Education to study the problem of disadvantaged student access to public universities and monitor the progress. For the five BOG univer sities, the IBHE determined that one plan should be developed. The plan was developed for the BOG by the Systemwide Committee on the Specific Student Groups, said Meyer. The proposal's implementing strategy is intended to strengthen relations between school districts and community colleges in which disad vantaged students y Swedringer, a dental hygenist from Lakeland College in afternoon at the dental clinic in the Health Service building. predominate, she said. n, examines Mike Weter, a junior zoology major, Thursday Mollie West, director of public affairs at Chicago State University, said that an annual report from each university stern cutsadmissions off. -

Music List (PDF)

Artist Title disc# 311 Down 475 702 Where My Girls At? 503 20 fingers short dick man 482 2pac changes 491 2Pac California Love 152 2Pac How Do You Want It 152 3 Doors Down Here Without You 452 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 201 3 doors down loser 280 3 Doors Down when I'm gone 218 3 Doors Down Be Like That 224 38 Special Hold On Loosely 163 3lw No more (baby I'm a do right) 402 4 Non Blondes What's Up 106 50 Cent Disco Inferno 510 50 cent & nate dogg 21 questions 483 50 cent & nate dogg in da club 483 5th Dimension, The aquarius/let the sunshine in 91 5th Dimension, The One Less Bell To Answer 93 69 Boyz Tootsee Roll 205 98 Degrees Because Of You 156 98 Degrees Because Of You (Dance Remix) 362 98 degrees Give me just one Night 383 98 Degrees Hardest Thing, the 162 98 Degrees I Do 162 98 Degrees My Everything 201 98 Degrees Why (Are We Still Friends) 233 A3 Woke Up This Morning 149 Aaliyah Are You That Somebody? 156 aaliyah Try again 401 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 227 Abba Dancing Queen 102 ABBA FERNANDO 73 ABBA Waterloo 147 ABC Be Near Me 444 ABC When Smokey Sings 444 ABDUL, PAULA Blowing Kisses In The Wind 446 ABDUL, PAULA Rush Rush 446 ABDUL, PAULA STRAIGHT UP 27 ABDUL, PAULA Vibeology 444 AC/DC Back In Black 161 AC/DC Hells Bells 161 AC/DC Highway To Hell 295 AC/DC Stiff Upper Lip 295 AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie 295 AC/dc You shook me all night long 108 Ace Of Base Beautiful Life 8 Ace of Base Don't Turn Around 154 Ace Of Base Sign, The 206 AD LIBS BOY FROM NEW YORK CITY, THE 49 adam ant goody two shoes 108 ADAMS, BRYAN (EVERYTHING I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU