STEPHANIE COONTZ the Way We Never Were

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

They Hate US for Our War Crimes: an Argument for US Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the Post-Human Rights

UIC Law Review Volume 52 Issue 4 Article 4 2019 They Hate U.S. for Our War Crimes: An Argument for U.S. Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the ost-HumanP Rights Era, 53 UIC J. MARSHALL. L. REV. 1011 (2019) Michael Drake Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Michael Drake, They Hate U.S. for Our War Crimes: An Argument for U.S. Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the Post-Human Rights Era, 53 UIC J. MARSHALL. L. REV. 1011 (2019) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol52/iss4/4 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THEY HATE U.S. FOR OUR WAR CRIMES: AN ARGUMENT FOR U.S. RATIFICATION OF THE ROME STATUTE IN LIGHT OF THE POST-HUMAN RIGHTS ERA MICHAEL DRAKE* I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................... 1012 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................ 1014 A. Continental Disparities ......................................... 1014 1. The International Process in Africa ............... 1014 2. The National Process in the United States of America ............................................................ 1016 B. The Rome Statute, the ICC, and the United States ................................................................................. 1020 1. An International Court to Hold National Leaders Accountable ...................................................... 1020 2. The Aims and Objectives of the Rome Statute .......................................................................... 1021 3. African Bias and U.S. -

Download Transcript

Gaslit Nation Transcript 17 February 2021 Where Is Christopher Wray? https://www.patreon.com/posts/wheres-wray-47654464 Senator Ted Cruz: Donald seems to think he's Michael Corleone. That if any voter, if any delegate, doesn't support Donald Trump, then he's just going to bully him and threaten him. I don't know if the next thing we're going to see is voters or delegates waking up with horse's heads in their bed, but that doesn't belong in the electoral process. And I think Donald needs to renounce this incitement of violence. He needs to stop asking his supporters at rallies to punch protestors in the face, and he needs to fire the people responsible. Senator Ted Cruz: He needs to denounce Manafort and Roger Stone and his campaign team that is encouraging violence, and he needs to stop doing it himself. When Donald Trump himself stands up and says, "If I'm not the nominee, there will be rioting in the streets.", well, you know what? Sol Wolinsky was laughing in his grave watching Donald Trump incite violence that has no business in our democracy. Sarah Kendzior: I'm Sarah Kendzior, the author of the bestselling books The View from Flyover Country and Hiding in Plain Sight. Andrea Chalupa: I'm Andrea Chalupa, a journalist and filmmaker and the writer and producer of the journalistic thriller Mr. Jones. Sarah Kendzior: And this is Gaslit Nation, a podcast covering corruption in the United States and rising autocracy around the world, and our opening clip was of Senator Ted Cruz denouncing Donald Trump's violence in an April 2016 interview. -

National Occupational Research Agenda Update July, 1997

National Occupational Research Agenda Update July, 1997 National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Howard Hoffman (National Institute on Rolf Eppinger (National Highway Transporta- NORA Teams Deafness and Communicative Disorders) tion Safety Administration) John Casali (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and Stephen Luchter (National Highway State University) Transportation Safety Administration) Bold type indicates team leader(s) Patricia Brogan (Ford Motor Company) Tim Pizatella (NIOSH) 1. Allergic & Irritant Dermatitis Randy Tubbs (NIOSH) 8. Indoor Environment Boris Lushniak (NIOSH) Mark Mendell (NIOSH) Alan Moshell (National Institute of Arthritis 5. Infectious Diseases William Fisk (Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory) and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases) William Cain (University of California San Carol Burnett (NIOSH) Robert Mullan (NIOSH) Diego) David Bernstein (University of Cincinnati) William Denton (Denton International) Cynthia Hines (NIOSH) Frances Storrs (Oregon Health Sciences Craig Shapiro (National Center for Infectious Darryl Alexander (American Federation of University) Diseases) Teachers) G. Frank Gerberick (Proctor & Gamble Adelisa Panlilio (National Center for David Spannbauer (General Services Company) Infectious Diseases) Administration) Mark Boeniger (NIOSH) Jack Parker (NIOSH) Donald Milton (Harvard University) Michael Luster (NIOSH) Joel Breman (Fogarty -

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 02/16/2021 11:18:01 AM

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 02/16/2021 11:18:01 AM 02/12/21 Friday This material is distributed by Ghebi LLC on behalf of Federal State Unitary Enterprise Rossiya Segodnya International Information Agency, and additional information is on file with the Department of Justice, Washington, District of Columbia. Lincoln Project Faces Exodus of Advisers Amid Sexual Harassment Coverup Scandal by Morgan Artvukhina Donald Trump was a political outsider in the 2016 US presidential election, and many Republicans refused to accept him as one of their own, dubbing themselves "never-Trump" Republicans. When he sought re-election in 2020, the group rallied in support of his Democratic challenger, now the US president, Joe Biden. An increasing number of senior figures in the never-Trump political action committee The Lincoln Project (TLP) have announced they are leaving, with three people saying Friday they were calling it quits in the wake of a sexual assault scandal involving co-founder John Weaver. "I've always been transparent about all my affiliations, as I am now: I told TLP leadership yesterday that I'm stepping down as an unpaid adviser as they sort this out and decide their future direction and organization," Tom Nichols, a “never-Trump” Republican who supported the group’s effort to rally conservative support for US President Joe Biden in the 2020 election, tweeted on Friday afternoon. Nichols was joined by another adviser, Kurt Bardella and by Navvera Hag, who hosted the PAC’s online show “The Lincoln Report.” Late on Friday, Lincoln Project co-founder Steve Schmidt reportedly announced his resignation following accusations from PAC employees that he handled the harassment scandal poorly, according to the Daily Beast. -

Flores, Sarah Isgur

Document ID: 0.7.13976.5130 From: Shawna Thomas <[email protected]> To: Flores, Sarah Isgur (OPA) <[email protected]> Cc: Bcc: Subject: Re: Follow up Date: Thu Mar 02 2017 09:19:33 EST Attachments: Thanks. On 2 March 2017 at 07:57, Flores, Sarah Isgur (OPA) <[email protected]> wrote: Sessions answered honestly and correctly the questions that he was asked by Franken and Leahy in written testimony. He did not speak to any Russian officials as a surrogate of the campaign nor any Russian official about the 2016 campaign. From: Flores, Sarah Isgur (OPA) [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, March 2, 2017 7:56 AM To: Shawna Thomas <[email protected]>; Flores, Sarah Isgur. (OPA) <Sarah.Isgur. [email protected]> Subject: RE: Follow up It wasn’t false From: Shawna Thomas [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, March 2, 2017 7:50 AM To: Flores, Sarah Isgur. (OPA) <[email protected]> Subject: Follow up Thanks. Are you concerned about his testimony in his confirmation hearing being false? Isn't that perjury? Shawna Thomas DC Bureau Chief - Vice News c: (b)(6) @shawna On Mar 2, 2017, at 6:39 AM, Sarah Isgur Flores <(b)(6) > wrote: cc'ing my do one so you have it. I think its important to note that this was in the regular course of his work on armed services. He met 25 times with ambassadors last year. The day after this meeting, he met with the Ukranian ambassador. The meeting was in his senate office with two defense policy staffers--meaning, this wasn't some secret. -

Kellyanne Conway and Postfeminism: 'The Desert of the Real'

Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research Volume 18 Article 7 2019 Kellyanne Conway and Postfeminism: 'The Desert of the Real' L. Shelley Rawlins Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/kaleidoscope Recommended Citation Rawlins, L. Shelley (2019) "Kellyanne Conway and Postfeminism: 'The Desert of the Real'," Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research: Vol. 18 , Article 7. Available at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/kaleidoscope/vol18/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kellyanne Conway and Postfeminism: 'The Desert of the Real' Cover Page Footnote Acknowledgements: I thank my advisor and friend Dr. Craig Gingrich-Philbrook for his invaluable input on this work. I thank my mother Sandy Rawlins for sharing inspiring conversations with me and for her keen editing eye. I appreciate the reviewers’ helpful feedback and thank Kaleidoscope’s editorial staff, especially Shelby Swafford and Alex Davenport, for facilitating this publication process. L. Shelley Rawlins is a Doctoral Candidate at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale This article is available in Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/kaleidoscope/vol18/iss1/7 Kellyanne Conway and Postfeminism: ‘The Desert of the Real’ L. Shelley Rawlins Postfeminism is a slippery, contested, ambivalent, and inherently contradictory term – deployed alternately as an “empowering” identity label and critical theoretical lens. -

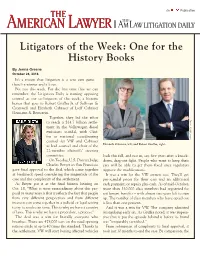

Litigators of the Week: One for the History Books

Litigators of the Week: One for the History Books By Jenna Greene October 28, 2016 It’s a truism that litigation is a zero sum game— there’s a winner and a loser. But not this week. For the first time that we can remember, the Litigation Daily is naming opposing counsel as our co-litigators of the week, a historic honor that goes to Robert Giuffra Jr. of Sullivan & Cromwell and Elizabeth Cabraser of Lieff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein. Together, they led the effort Photos: ALM/Courtesy to reach a $14.7 billion settle- ment in the Volkswagen diesel emissions scandal, with Giuf- fra as national coordinating counsel for VW and Cabraser as lead counsel and chair of the Elizabeth Cabraser, left, and Robert Giuffra, right. 22-member plaintiffs’ steering committee. back this fall, and not in, say, five years after a knock- On Tuesday, U.S. District Judge down, drag-out fight. People who want to keep their Charles Breyer in San Francisco cars will be able to get them fixed once regulators gave final approval to the deal, which came together approve the modifications. at breakneck speed considering the magnitude of the It was a win for the VW owners too. They’ll get case and the complexity of the settlement. pre-scandal prices for their cars and an additional As Breyer put it at the final fairness hearing on cash payment, or repairs plus cash. As of mid-October, Oct. 18, “What is most extraordinary about this pro- more than 330,000 class members had registered for posal in many ways is that it reflects the fact that people settlement benefits – with almost two years left to sign from very different perspectives and from different up. -

PCG Annual Report 2014-2015

HARVARD LAW SCHOOL Program on Corporate Governance Report of Activities, July 1, 2014 – June 30, 2015 A. Introduction and Executive Summary The Program on Corporate Governance seeks to contribute to policy, public discourse, and education in the field of corporate governance. It seeks to advance this mission in two inter- related ways: • Bridging the gap between academia and practice: The Program seeks to foster interaction between the worlds of academia and practice that will enrich both. Such interaction enables academic researchers to better understand the issues and the environment facing practitioners, thereby facilitating research that will be more relevant for practice. Interaction between academia and practice also keeps public and private decision-makers better informed about research activities in corporate governance, and enhances the public discourse on corporate governance. • Fostering policy-relevant research: The Program fosters empirical and policy research that sheds light on corporate governance questions facing public and private decision- makers. By providing relevant research that is grounded in the best methods of academic research, such projects can have an important impact on decision-making and public discourse in the field. The Program’s director is Professor Lucian Bebchuk, and other Harvard Law School faculty members contributing to its activities during 2014-15 were Robert Clark, John Coates, Alma Cohen, Allen Ferrell, Jesse Fried, Oliver Hart, Howell Jackson, Reinier Kraakman, Mark Ramseyer, Mark Roe, Robert Sitkoff, Holger Spamann, Leo Strine, Jr., and Guhan Subramanian. Also contributing to the Program’s activities were its Senior Fellows, Alon Brav, Stephen Davis, Assaf Hamdani, Oliver Hart, Ben W. Heineman, Jr., Robert J. -

As Clinics Collapse, a Rift in Trust Trump’S Camp Sunday, with Prospect of a Reprieve

ABCDE Prices may vary in areas outside metropolitan Washington. SU V1 V2 V3 V4 Cloudy, rain 36/33 • Tomorrow: Morning rain, breezy 53/26 B8 Democracy Dies in Darkness MONDAY, FEBRUARY 15, 2021 . $2 Many GOP Acquittal o∞cials see Inside the rise and swift downfall of P hiladelphia’s mass vaccination start-up virus relief widens as a lifeline divide Mayors, governors say in GOP Biden’s proposal i s vital to blunt economic pain FACTIONS SPLIT O N PATH FORWARD BY GRIFF WITTE Graham sees Trump as the ‘most potent force’ The pandemic has not been kind to Fresno, the poorest major city in California. The unemploy- BY AMY B WANG ment rate spiked above 10 per- cent and has stubbornly re- One day after the Senate ac- mained there. Violent crime has quitted former president Donald surged, as has homelessness. Tax Trump in his second impeach- revenue has plummeted as busi- ment trial, Republicans contin- nesses have shuttered. Lines at ued to diverge in what the future food banks are filled with first- of their party should be, with a timers. chasm widening between those But as bad as it’s been, things who want nothing to do with the could soon get worse: Having former president and those who frozen hundreds of jobs last year, openly embrace him. The divi- the city is now being forced to sion is playing out as Trump consider laying off 250 people, promises a return to politics and including police and firefighters, as both factions within the GOP to close a $31 million budget vow they will prevail in the 2022 shortfall. -

RUTH BEN-GHIAT Departments of History and Italian Studies, New York University [email protected], @Ruthbenghiat ______

1 RUTH BEN-GHIAT Departments of History and Italian Studies, New York University [email protected], www.ruthbenghiat.com, @ruthbenghiat _______________________________________________________________________ EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Professor of History and Italian Studies, New York University. Author. Commentator. Board and academic administrator experience. Advisor, Protect Democracy. Publisher, Lucid: A Newsletter about Abuses of Power: LinkedIn profile: https://www.linkedin.com/profile/view?id=77153272&trk=nav_responsive_tab_profile FIELDS OF EXPERTISE Fascism; Authoritarianism; Propaganda; World War Two; Empire; Modern and Contemporary Europe and Italy. EDUCATION PhD, Comparative History, Brandeis University. BA, History, magna cum laude, University of California, Los Angeles. GRANTS, FELLOWSHIPS, AWARDS Institute for Advanced Study, Andrew W. Mellon Member, School of Historical Studies, spring 2020. Edinburgh Gadda Prize for Best Book on 20th Century Italian Culture, 2019. Aldo and Jeanne Scaglione Award for Best Unpublished Manuscript in Italian Studies. Modern Language Association, 2014 (for Italian Fascism’s Empire Cinema). University Research Challenge Fund Grant, NYU, 2013-2014. Outstanding Service Award, Institute of International Education (for work with Scholar Rescue Fund), 2013. Modern Italian Studies Fellowship, Collegio Carlo Alberto, Turin, 2011-2012. John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, 2004-2005. National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship, 2004-2005. Trinity College Cesare Barbieri Grant in Italian History, 2003. Faculty Fellowship, Remarque Institute, NYU, spring 2002. Kluge Fellowship, Library of Congress, 1999-2000. Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Research Grant, 1999-2000. Faculty Fellowship and Ames Fund Junior Faculty Grant, Fordham University, 1997. Fulbright Research Scholar to Italy, 1993-1994. Fellow, Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1992-1993. American Philosophical Society Research Grant, 1993. -

Elezioniusa2020. Il Conto Alla Rovescia. Meno 70 Giorni

#elezioniUsa2020. Il conto alla rovescia. Meno 70 giorni Si apre oggi la convention repubblicana. Nonostante il Covid-19, non sarà virtuale ma in un luogo fisico, anche se in numeri ridotti. Trump non sarà presente in loco nella giornata della sua re-investitura come candidato repubblicano ma parlerà, inusitatamente per un evento di partito, dalla Casa Bianca. Secondo gli organizzatori la convention dovrebbe assomigliare alle puntate di “The Apprentice”, lo show condotto da Trump prima di lanciarsi in politica: sarà prevista quindi un’apparizione del presidente alla fine di ogni serata di convenzione. Tra i dieci interventi che andranno in prime time cinque saranno di familiari di Trump (la moglie Melania e i quattro figli). Nessun candidato presidente o vice delle passate elezioni sarà presente alla convention. Tra gli interventi vi saranno anche quelli dei McCloskey, la coppia di St. Louis che brandiva dei fucili contro i manifestanti di Black Lives Matter. Tra gli interventi che hanno suscitato perplessità in campo democratico vi è quello di Vernon Jones Vernon Jones, un deputato statale democratico in Georgia che ha deciso di sostenere Trump. I temi delle serate dovrebbero essere l’ordine pubblico, la ripresa economica e la lotta contro la “cancel culture”. La consigliera della Casa Bianca Kellyanne Conway ha annunciato che lascerà l’amministrazione alla fine di agosto. Suo marito, George Conway III, un feroce critico del presidente, ha annunciato che si ritirerà dal Lincoln Project, un’organizzazione che lavora per sconfiggere Trump a novembre. I Conway avevano trascorso gli ultimi anni in una faida pubblica su Trump: Kellyanne Conway lo difende in regolari apparizioni televisive e George Conway lo critica duramente su Twitter e in editoriali sul Washington Post. -

Next Solicitor General Can Expect Tough Road Under Trump by Andrew Strickler

Portfolio Media. Inc. | 111 West 19th Street, 5th Floor | New York, NY 10011 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] Next Solicitor General Can Expect Tough Road Under Trump By Andrew Strickler Law360, New York (February 15, 2017, 7:55 PM EST) -- President Donald Trump's pick for the usually coveted position of solicitor general should expect an unusually rocky tenure, experts say, given the legal battles already underway, criticisms the president has heaped on the judiciary and the likely difficulty of dissuading a president who shoots from the hip from pursuing untenable legal positions. Often described as the best legal job in the government, most solicitors general in recent decades have been able to focus on a short list of executive branch legal goals and high-profile cases headed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and have enjoyed a high level of deference from the justices. But fast-moving policy changes promised by the Trump administration on a wide range of complex issues like tax and trade will force the next SG to juggle a greater range of legal questions with wide repercussions and more politically fraught cases. And in light of Trump’s professed desire for undivided loyalty from his underlings, some experts are raising concerns that the SG's traditional behind-the-scenes role as an independent sounding board for the president and attorney general on legal issues will be eroded if Trump’s pick can’t dissuade his or her bosses from taking shaky positions. Mayer Brown LLP managing partner Kenneth Geller, who served in the Solicitor General’s Office during the Ford, Carter and Reagan administrations, said the executive branch wins so many cases at the Supreme Court in large part because of the office’s credibility with the court, built up over decades of well-reasoned arguments and through shifting political winds.