The Incidence of Hip Fractures in Norway –Accuracy of the National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MHSUDS Information Notice No.: 16-051

State of California—Health and Human Services Agency Department of Health Care Services JENNIFER KENT EDMUND G. BROWN JR. DIRECTOR GOVERNOR DATE: October 7, 2016 MHSUDS INFORMATION NOTICE N O.: 16-051 TO: COUNTY BEHAVIORAL HEALTH DIRECTORS COUNTY BEHAVIORAL HEALTH DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION OF CALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA COUNCIL OF COMMUNITY BEHAVIORAL HEALTH AGENCIES CALIFORNIA ALLIANCE OF CHILD AND FAMILY SERVICES SUBJECT: IMPLEMENTATION OF THE DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL OF MENTAL DISORDERS (DSM-5), FIFTH EDITION REFERENCES: MHSD INFORMATION NOTICE 13-22 MHSUDS INFORMATION NOTICE 14-040 MHSUDS INFORMATION NOTICE 15-003 MHSUDS INFORMATION NOTICE 15-030 PURPOSE The purpose of this Information Notice is to direct Mental Health Plans (MHPs) to use the American Psychiatric Association (APA) DS M-5 to make diagnostic determinations for the purposes of determining if beneficiaries meet medical necessity criteria for Medi-Cal specialty mental health services (SMHS). This Information Notice updates information previously provided in Mental Health Services Division (MHSD) Information Notice 13-22. BACKGROUND The APA issued the DSM-5 on May 20, 2013. The DSM-5 provides diagnostic criteria and codes as well as corresponding International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) codes. Since March 2013, the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) has collaborated with internal and external stakeholders and partners to address implementation issues specific to SMHS related to the DSM-5. Mental Health & Substance Use Disorder Services 1501 Capitol Avenue, MS 4000, P.O. Box 997413 Sacramento, CA 95899-7413 Phone: (916) 440-7800 Fax: (916) 319-8219 Internet Address: www.dhcs.ca.gov MHSUDS INFORMATION NOTICE N O.: 16-051 October 7, 2016 Page 2 DHCS has issued previous MHSUDS Information Notices1 that instruct MHPs to report only ICD-10 codes for claiming and diagnoses reporting purposes and provide ICD-10 procedural and diagnosis crosswalk documents f or SMHS. -

ICD-10 International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

ICD-10 International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision Volume 2 Instruction manual 2010 Edition WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. - 10th revision, edition 2010. 3 v. Contents: v. 1. Tabular list – v. 2. Instruction manual – v. 3. Alphabetical index. 1.Diseases - classification. 2.Classification. 3.Manuals. I.World Health Organization. II.ICD-10. ISBN 978 92 4 154834 2 (NLM classification: WB 15) © World Health Organization 2011 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (http://www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Clinical Vocabularies for Global Real World Evidence (RWE) | Evidera

Clinical Vocabularies for Global RWE Analysis Don O’Hara, MS Senior Research Associate, Real-World Evidence, Evidera Vernon F. Schabert, PhD Senior Research Scientist, Real-World Evidence, Evidera Introduction significant volume of real-world evidence (RWE) analyses continue to be conducted with data A repurposed from healthcare administrative Don O’Hara Vernon F. Schabert databases. The range of sources represented by those databases has grown in response to demand for richer description of patient health status and outcomes. information for improved quality and coordination Data availability, including the range of available data of care, often using standardized messaging systems sources, has grown unevenly across the globe in response such as Health Level 7 (HL7). These messages are to country-specific market and regulatory dynamics. only as good as the standardization of codes between Nonetheless, as demand globalizes for RWE insights from message senders and receivers, which motivates the databases, those demands increase pressure on analysts encoding of facts using common code sets. The second to find ways to bridge differences between local data is the increased availability of common data models to sources to achieve comparable insights across regions. standardize the extraction and analysis of these data for RWE and drug safety purposes. While common data One of the challenges in bridging differences across models make compromises on the structure of tables databases is the codes used to represent key clinical and fields extracted from healthcare systems such as facts. Historically, RWE database studies have leveraged electronic medical records (EMR) and billing systems, local code sets for cost-bearing healthcare services they can improve consistency and replicability of analyses such as drugs, procedures, and laboratory tests. -

Non-Interventional (Ni) Study Report

Apixaban B0661018 NON-INTERVENTIONAL STUDY REPORT FINAL, 20 May 2015 NON-INTERVENTIONAL (NI) STUDY REPORT PASS information Title Post-approval safety study (PASS) of the utilization pattern of apixaban in the Netherlands Protocol number B0661018 Version identifier of the final study report 1.0 Date of last version of the final study 20 May 2016 report EU Post Authorisation Study (PAS) ENCEPP/SDPP/5177 register number Active substance B01AF02 apixaban Medicinal product Eliquis -2016 15:22 y Product reference EU/1/11/691/001-015 Procedure number EMEA/H/C/002148 Marketing Authorisation Holder (MAH) Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer EEIG roved On: 23-Ma Joint PASS No pp Research question and objectives This is a descriptive study using roved\A retrospectively collected data from pp electronic health record databases. The study describes the utilization pattern of apixaban in the Netherlands (01 Dec 2011 through 31 Dec 2014). The study aimed 1) to estimate the proportions of apixaban users who receive the drug for the approved indications at the time of the first apixaban dispensing and 2) to describe the characteristics of the patients who were prescribed apixaban for 090177e188105755\A PFIZER CONFIDENTIAL Page 1 Approved v 1.0 930102376 1.0 Apixaban B0661018 NON-INTERVENTIONAL STUDY REPORT FINAL, 20 May 2015 on-label and off-label indications. Country(-ies) of study The Netherlands Author Marketing Authorisation Holder(s) Marketing Authorisation Holder(s) Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer EEIG -2016 15:22 y MAH contact person roved On: 23-Ma pp roved\A pp This document contains confidential information belonging to Pfizer. -

(Child Core Set) Technical Specifications and Reso

Core Set of Children's Health Care Quality Measures for Medicaid and CHIP (Child Core Set) Technical Specifications and Resource Manual for Federal Fiscal Year 2019 Reporting February 2019 Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services This page left blank for double-sided copying ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For Proprietary Codes: CPT® codes copyright 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. CPT is a trademark of the American Medical Association. No fee schedules, basic units, relative values or related listings are included in CPT. The AMA assumes no liability for the data contained herein. Applicable FARS/DFARS restrictions apply to government use. SNOMED CLINICAL TERMS (SNOMED CT®) copyright 2004-2018 The International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation. All Rights Reserved. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) is published by the World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-9-CM is an official Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standard. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Procedure Coding System (ICD-9-PCS) is published by the World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-9-PCS is an official Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standard. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) is published by the World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-10-CM is an official Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standard. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS) is published by the World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-10-PCS is an official Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standard. This material contains content from LOINC® (http://loinc.org). -

Inappropriate Primary Diagnosis Codes Policy, Professional

Commercial Reimbursement Policy CMS 1500 Policy Number 2020R0122C Inappropriate Primary Diagnosis Codes Policy, Professional IMPORTANT NOTE ABOUT THIS REIMBURSEMENT POLICY You are responsible for submission of accurate claims. This reimbursement policy is intended to ensure that you are reimbursed based on the code or codes that correctly describe the health care services provided. UnitedHealthcare reimbursement policies may use Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®*), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) or other coding guidelines. References to CPT or other sources are for definitional purposes only and do not imply any right to reimbursement. This reimbursement policy applies to all health care services billed on CMS 1500 forms and, when specified, to those billed on UB04 forms. Coding methodology, industry-standard reimbursement logic, regulatory requirements, benefits design and other factors are considered in developing reimbursement policy. This information is intended to serve only as a general reference resource regarding UnitedHealthcare’s reimbursement policy for the services described and is not intended to address every aspect of a reimbursement situation. Accordingly, UnitedHealthcare may use reasonable discretion in interpreting and applying this policy to health care services provided in a particular case. Further, the policy does not address all issues related to reimbursement for health care services provided to UnitedHealthcare enrollees. Other factors affecting reimbursement may supplement, modify or, in some cases, supersede this policy. These factors may include, but are not limited to: legislative mandates, the physician or other provider contracts, the enrollee’s benefit coverage documents and/or other reimbursement, medical or drug policies. Finally, this policy may not be implemented exactly the same way on the different electronic claims processing systems used by UnitedHealthcare due to programming or other constraints; however, UnitedHealthcare strives to minimize these variations. -

G11.11: New Icd-10-Cm (Diagnosis) Code for Friedreich's Ataxia

G11.11: NEW ICD-10-CM (DIAGNOSIS) CODE FOR FRIEDREICH’S ATAXIA EFFECTIVE OCTOBER 1, 2020 CALL TO ACTION – PROVIDE THIS INFO TO YOUR CLINICIANS Starting on October 1, 2020, at your next appointments with any clinician, ask that your ICD-10 diagnosis code for FA be updated to G11.11 (previous code for FA was G11.1 > add a “1” > G11.11). Your clinician can use multiple ICD-10 diagnosis codes based on your need for medical care (e.g. G11.11 – FA, I49.9 - cardiac arrhythmia, Z13.1 – encounter for screening for diabetes mellitus). Please email [email protected] if you or your clinician has questions regarding use of G11.11 PREVIOUS CODING FOR FRIEDREICH’S ATAXIA ICD-9 system had a specific code for FA: 334.0 In conversion to ICD-10, the code for FA became less specific because it covered a group of conditions described as “early-onset cerebellar ataxias”. The previous FA ICD-10 diagnosis code was G11.1. BENEFITS OF THE NEW FA-SPECIFIC ICD-10-CM CODE G11.11 • Fewer rejected health insurance claims • Payer coverage determinations without need for direct access to patients’ medical records for review of medical necessity • Monitor adherence to clinical management guidelines and track care outcomes • Evaluate symptom progression of FA; additional ICD-10 codes can be applied to reflect context of FA diagnosis, such as for falls, surgeries, medications, and co-morbidities • Enhanced ability to track disease prevalence BACKGROUND ON ICD CODING SYSTEM ICD = International Classification of Diseases The ICD coding system was established by the World Health Organization; currently used by ~100 countries for reporting cause of death and epidemiology statistics. -

ROR*1.5*36 User Manual

Clinical Case Registries (CCR) Version 1.5 User Manual Documentation Revised May 2020 For Patch ROR*1.5*36 Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Enterprise Development Health Data Systems – Registries THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Revision History Date Description Author Role May, 2020 Final release for Patch ROR*1.5*36. See Table REDACTED Project Manager 54Table 52 for Details. M Developer M Developer Software QA Analyst Software QA Analyst Delphi Developer November, Final release for Patch ROR*1.5*35. See Table REDACTED Project Manager 2019 52Table 52 for Details. M Developer M Developer Software QA Analyst Delphi Developer March, 2019 Final release for Patch ROR*1.5*34. See Table REDACTED Project Manager 50 for Details. M Developer M Developer Software QA Analyst Delphi Developer July, 2018 Final release for Patch ROR*1.5*33. See Table REDACTED Project Manager 48Table 52 for Details. M Developer M Developer Software QA Analyst Delphi Developer April, 2018 Final release for Patch ROR*1.5*32. See Table REDACTED Project Manager 46Error! Reference source not found. for Details. M Developer Software QA Analyst Delphi Developer May, 2020 Clinical Case Registries ROR*1.5*36 i User Manual Date Description Author Role November, Final release for Patch ROR*1.5*31. See Table REDACTED Project Manager 2017 44 for Details. M Developer M Developer Software QA Analyst Software QA Analyst Delphi Developer May, 2017 Final release for Patch ROR*1.5*30. See Table REDACTED Project Manager 42 for Details. M Developer SQA Analyst Delphi Developer December, Final release for Patch ROR*1.5*29. -

ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting FY 2018 (October 1, 2017 - September 30, 2018)

ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting FY 2018 (October 1, 2017 - September 30, 2018) Narrative changes appear in bold text Items underlined have been moved within the guidelines since the FY 2017 version Italics are used to indicate revisions to heading changes The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), two departments within the U.S. Federal Government’s Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) provide the following guidelines for coding and reporting using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM). These guidelines should be used as a companion document to the official version of the ICD-10- CM as published on the NCHS website. The ICD-10-CM is a morbidity classification published by the United States for classifying diagnoses and reason for visits in all health care settings. The ICD-10-CM is based on the ICD-10, the statistical classification of disease published by the World Health Organization (WHO). These guidelines have been approved by the four organizations that make up the Cooperating Parties for the ICD-10-CM: the American Hospital Association (AHA), the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA), CMS, and NCHS. These guidelines are a set of rules that have been developed to accompany and complement the official conventions and instructions provided within the ICD-10-CM itself. The instructions and conventions of the classification take precedence over guidelines. These guidelines are based on the coding and sequencing instructions in the Tabular List and Alphabetic Index of ICD-10-CM, but provide additional instruction. -

The Aftershocks of ICD-10 MAOFP

The Aftershocks of ICD-10 MAOFP Presented by Traci Cook, CPC Affiliated Medical Billing, LLC January 22, 2016 Alma | Ann Arbor | Flint | Greater Detroit | Kalamazoo | Lansing | Midland | Saginaw (866) 493-9830 | www.yeoandyeo.com Topics . The Benefits of ICD-10 . Glitches & How We Detect Them . Where Do You Go for Help for ICD-10 Related Issues? The Benefits of ICD-10 Benefits The American Health Information Management Association reported that…. “The mountain of new data that will be generated by ICD- 10 can also be mined for the greater good of public health, allowing the U.S. to track and respond to global health threats faster and compare best practices with the international community.” Benefits Replacing ICD-9-CM with ICD-10-CM provides higher quality information for measuring healthcare service, quality, safety, and efficacy. This in turn provides better data for: • Quality measurement and medical error reduction (patient safety) • Outcomes measurement • Clinical research • Clinical, financial, and administrative performance measurement • Health policy planning • Operational and strategic planning and healthcare delivery system design • Payment systems design and claims processing • Reporting on use and effects of new medical technology • Provider profiling Benefits • Refinements to current reimbursement systems, such as severity- adjusted DRG systems • Pay-for-performance programs • Public health and bioterrorism monitoring • Managing care and disease processes • Educating consumers on costs and outcomes of treatment options Benefits- Laterality . Laterality in the diagnostic codes can explain that the treatment provided is for the contralateral side. Laterality in the diagnostic codes may help to define that treatment today is not related to treatment provided in the global period. -

Using SAS® to Analyze ICD-9 and ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes Found in Administrative Health-Care Data Kathy Fraeman, Evidera

Paper 3117-2019 Using SAS® to Analyze ICD-9 and ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes Found in Administrative Health-Care Data Kathy Fraeman, Evidera ABSTRACT Administrative health-care data – including insurance claims data, electronic medical records (EMR) data, and hospitalization data – contains standardized diagnosis codes to identify diseases and other medical conditions. These codes use the short-form name of ICD, which stands for International Classification of Diseases. Much of the currently available health-care data contains the ninth version of these codes, referred to as ICD-9. Although, the more recent 10th version, ICD-10, is becoming more common in health-care data. These diagnosis codes are typically saved as character variables, are often stored in arrays of multiple codes representing primary and secondary diagnoses and can be associated with either outpatient medical visits or inpatient hospitalizations. SAS® text processing functions, array processing, and the SAS colon modifier can be used to analyze the text of these codes and to identify similar codes or ranges of ICD codes. In epidemiologic analyses, groups of multiple ICD diagnosis codes are typically used to define more general comorbidities or medical outcomes. These disease definitions based on multiple ICD diagnosis codes, also known as coding algorithms, can either be hardcoded in a SAS program or defined externally from the programming. When coding algorithm definitions based on ICD codes are stored externally, the definitions can be read into SAS, transformed to SAS format, and dynamically converted into SAS programming statements. INTRODUCTION The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is maintained by the World Health Organization (WHO) and is described by the WHO as the international “…standard diagnostic tool for epidemiology, health management and clinical purposes.” ICD diagnosis codes provide a standardized system for classifying diseases, and for classifying a variety of signs, symptoms, and external causes of injury or disease. -

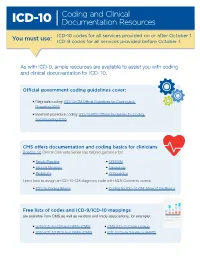

ICD-10: Coding and Clinical Documentation Resources

Coding and Clinical ICD-10 Documentation Resources You must use: ICD-10 codes for all services provided on or after October 1 ICD-9 codes for all services provided before October 1 As with ICD-9, ample resources are available to assist you with coding and clinical documentation for ICD-10. Official government coding guidelines cover: • Diagnosis coding: ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting 2016 • Inpatient procedure coding: ICD-10-PCS Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting 2016 CMS offers documentation and coding basics for clinicians Road to 10 Clinical Concepts Series has tailored guidance for: • Family Practice • OB/GYN • Internal Medicine • Cardiology • Pediatrics • Orthopedics Learn how to assign an ICD-10-CM diagnosis code with MLN Connects videos: • ICD-10 Coding Basics • Coding for ICD-10-CM: More of the Basics Free lists of codes and ICD-9/ICD-10 mappings are available from CMS as well as vendors and trade associations, for example: • 2016 ICD-10-CM and GEMs (CMS) • CMS ICD-10 Code Lookup • 2016 ICD-10-PCS and GEMs (CMS) • ICD-10 Code Translator (AAPC) Coding and Clinical ICD-10 Documentation Resources • Several free and low-cost smartphone apps are available on Google Play and the Apple Store. • Many electronic health record (EHR) products and practice management systems prompt users for required documentation and feature computer-assisted coding. • Some system vendors and clearinghouses offer training to customers and potential customers. • Some health care trade associations and medical societies provide coding resources at no or little cost to their members, with premium costs sometimes charged to nonmembers.