Download Full Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of a National Lockdown in Response to COVID-19 Pandemic on the Prevalence of Clinical Symptoms in the Population

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.27.20076000; this version posted December 28, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC 4.0 International license . The effect of a national lockdown in response to COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of clinical symptoms in the population *1,2 *1,2 *1,2 *1,2,3 *1,2 1,2 Ayya Keshet , Amir Gavrieli , Hagai Rossman , Smadar Shilo , Tomer Meir , Tal Karady , Amit 1,2 1,2 1,2 1,2 1,2 4 4 Lavon , Dmitry Kolobkov , Iris Kalka , Saar Shoer , Anastasia Godneva , Ori Cohen, Adam Kariv , Ori Hoch , 4 4 5 5 2 6 4 Mushon Zer-Aviv , Noam Castel , Anat Ekka Zohar , Angela Irony , Benjamin Geiger , Yuval Dor , Dorit Hizi , 7 5, 8 1,2,☨ Ran Balicer , Varda Shalev , Eran Segal * Equal contribution 1 Department of Computer Science and Applied Mathematics, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel. 2 Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel. 3 Pediatric Diabetes Unit, Ruth Rappaport Children’s Hospital, Rambam Healthcare Campus, Haifa, Israel. 4 The public knowledge workshop, 26 Saadia Gaon st. Tel Aviv 5 Epidemiology and Database Research Unit, Maccabi Healthcare Services, Tel Aviv, Israel. 6 School of Medicine-IMRIC-Developmental Biology and Cancer Research, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. 7 Clalit Research Institute, Clalit Health Services, Tel Aviv, Israel. 8 School of Public Health, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel. -

The Beit Shemesh Running Club

The Beit Shemesh Running Club Marathoners Unite Religiously Diverse Israeli City By Hillel Kuttler pon completing each Monday’s 90-min- Strous could also have been referring to the ath- ute group run at 10:30 p.m., Rael Strous letic group to which he belongs, the Beit Shemesh Utakes leave of his mates and drives to a Running Club. The club unites disparate Jewish nearby bakery whose fresh-from-the-oven whole segments of society around a common appetite wheat rolls he craves. for pavement and trails, then sends them and Dripping 10 miles’ worth of street-pounding their differences home until the next workout. sweat and still clad in running shorts, Strous tends Its members and town officials view the run- to draw gazes and conversational interest from the ning club as a stark example of sports’ power to black-hatted, black-coated ultra-Orthodox men foster tolerance and inclusion. That is no small Members of the Beit who likewise visit the bakery for a late nibble here feat, especially following a series of ugly incidents Shemesh Running Club, in Beit Shemesh, an unassuming city of 85,000, in late 2011 near a Beit Shemesh elementary Shlomo Hammer and his 20 miles west of Jerusalem. The curiosity seekers school that had just opened on property that father Naftali Hammer inquire about Strous’ workout; he asks what Jewish adjoins—but also divides—the separate neigh- (front right and front scholarly texts they’ve been studying. borhoods where Modern Orthodox and ultra- left), stretching before “It’s just a bunch of guys getting together, Orthodox Jews live. -

Geography and Politics: Maps of “Palestine” As a Means to Instill Fundamentally Negative Messages Regarding the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center at the Center for Special Studies (C.S.S) Special Information Bulletin November 2003 Geography and Politics: Maps of “Palestine” as a means to instill fundamentally negative messages regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict The maps of “Palestine” distributed by the Palestinian Authority and other PA elements are an important and tangible method of instilling fundamentally negative messages relating to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. These include ignoring the existence of the State of Israel, and denying the bond between the Jewish people and the Holyland; the obligation to fulfill the Palestinian “right of return”; the continuation of the “armed struggle” for the “liberation” of all of “Palestine”, and perpetuating hatred of the State of Israel. Hence, significant changes in the maps of “Palestine” would be an important indicator of a real willingness by the Palestinians to recognize the right of Israel to exist as a Jewish state and to arrive at a negotiated settlement based on the existence of two states, Israel and Palestine, as envisaged by President George W. Bush in the Road Map. The map features “Palestine” as distinctly Arab-Islamic, an integral part of the Arab world, and situated next to Syria, Egypt and Lebanon. Israel is not mentioned. (Source: “Natioal Education” 2 nd grade textbook, page 16, 2001-2002). Abstract The aim of this document is to sum up the findings regarding maps of “Palestine” (and the Middle East) circulated in the Palestinian areas by the PA and its institutions, and by other organizations (including research institutions, charities, political figures, and terrorist organizations such as Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad). -

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Israel Report

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Report Israel National | 1 Table of content: Israel National Report for Habitat III Forward 5-6 I. Urban Demographic Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 7-15 1. Managing rapid urbanization 7 2. Managing rural-urban linkages 8 3. Addressing urban youth needs 9 4. Responding to the needs of the aged 11 5. Integrating gender in urban development 12 6. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 13 II. Land and Urban Planning: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 16-22 7. Ensuring sustainable urban planning and design 16 8. Improving urban land management, including addressing urban sprawl 17 9. Enhancing urban and peri-urban food production 18 10. Addressing urban mobility challenges 19 11. Improving technical capacity to plan and manage cities 20 Contributors to this report 12. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 21 • National Focal Point: Nethanel Lapidot, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry III. Environment and Urbanization: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban of Construction and Housing Agenda 23-29 13. Climate status and policy 23 • National Coordinator: Hofit Wienreb Diamant, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry of Construction and Housing 14. Disaster risk reduction 24 • Editor: Dr. Orli Ronen, Porter School for the Environment, Tel Aviv University 15. Minimizing Transportation Congestion 25 • Content Team: Ayelet Kraus, Ira Diamadi, Danya Vaknin, Yael Zilberstein, Ziv Rotem, Adva 16. Air Pollution 27 Livne, Noam Frank, Sagit Porat, Michal Shamay 17. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 28 • Reviewers: Dr. Yodan Rofe, Ben Gurion University; Dr. -

SCHOLARSHIP OPPORTUNITIES at TAU the International MA

SCHOLARSHIP OPPORTUNITIES AT TAU The International MA Program in Ancient Israel Studies: Archaeology and History of the Land of the Bible at Tel Aviv University is pleased to announce three scholarship opportunities for the academic year 2015-2016. 1. $13,000 US AYALIM TUITION ASSISTANCE SCHOLARSHIP A number of $13,000 US tuition assistance scholarships are offered to students who meet the following requirements: * Applicant's age must range from 21 to 30. * Applicant must be recognized by Masa Israel Journey (according to Masa's criteria for scholarships). 2. $2,500/ 5,000 US TUITION ASSISTANCE SCHOLARSHIPS $2,500/ 5,000 USD tuition assistance scholarships will be granted to a number of students with proven records of academic excellence who wish to broaden their knowledge and understanding of Ancient Israel. Scholarships for the academic year of 2015-2016 will be granted by the academic committee of the Department of Archaeology and Near Eastern Cultures based on the following: * Academic CV * Final transcript from last academic establishment * Abstract of the final paper submitted to the last academic establishment 3. FULL TUITION SCHOLARSHIPS FOR STUDENTS FROM CHINA Full tuition scholarships will be awarded based on academic excellence, and will allow students from China to study the archaeology and history of the Land of the Bible - IN the land of the Bible, at one of the most prestigious programs currently available in the field of Ancient Israel Studies. A number of accepted students will also be awarded free dormitories and living expense grants, in addition to full tuition scholarships. Admission requirements for students from China: * Academic achievements: Students must have a GPA of 3 or above, or an average score of 80% from their BA degree. -

THRESHING FLOORS AS SACRED SPACES in the HEBREW BIBLE by Jaime L. Waters a Dissertation Submitted to the Johns Hopkins Universit

THRESHING FLOORS AS SACRED SPACES IN THE HEBREW BIBLE by Jaime L. Waters A dissertation submitted to The Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland August 2013 © 2013 Jaime L. Waters All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Vital to an agrarian community’s survival, threshing floors are agricultural spaces where crops are threshed and winnowed. As an agrarian society, ancient Israel used threshing floors to perform these necessary activities of food processing, but the Hebrew Bible includes very few references to these actions happening on threshing floors. Instead, several cultic activities including mourning rites, divination rituals, cultic processions, and sacrifices occur on these agricultural spaces. Moreover, the Solomonic temple was built on a threshing floor. Though seemingly ordinary agricultural spaces, the Hebrew Bible situates a variety of extraordinary cultic activities on these locations. In examining references to threshing floors in the Hebrew Bible, this dissertation will show that these agricultural spaces are also sacred spaces connected to Yahweh. Three chapters will explore different aspects of this connection. Divine control of threshing floors will be demonstrated as Yahweh exhibits power to curse, bless, and save threshing floors from foreign attacks. Accessibility and divine manifestation of Yahweh will be demonstrated in passages that narrate cultic activities on threshing floors. Cultic laws will reveal the links between threshing floors, divine offerings and blessings. One chapter will also address the sociological features of threshing floors with particular attention given to the social actors involved in cultic activities and temple construction. By studying references to threshing floors as a collection, a research project that has not been done previously, the close relationship between threshing floors and the divine will be visible, and a more nuanced understanding of these spaces will be achieved. -

IDF Special Forces – Reservists – Conscientious Objectors – Peace Activists – State Protection

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: ISR35545 Country: Israel Date: 23 October 2009 Keywords: Israel – Netanya – Suicide bombings – IDF special forces – Reservists – Conscientious objectors – Peace activists – State protection This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on suicide bombs in 2000 to January 2002 in Netanya. 2. Deleted. 3. Please provide any information on recruitment of individuals to special army units for “chasing terrorists in neighbouring countries”, how often they would be called up, and repercussions for wanting to withdraw? 4. What evidence is there of repercussions from Israeli Jewish fanatics and Arabs or the military towards someone showing some pro-Palestinian sentiment (attending rallies, expressing sentiment, and helping Arabs get jobs)? Is there evidence there would be no state protection in the event of being harmed because of political opinions held? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on suicide bombs in 2000 to January 2002 in Netanya. According to a 2006 journal article published in GeoJournal there were no suicide attacks in Netanya during the period of 1994-2000. No reports of suicide bombings in 2000 in Netanya were found in a search of other available sources. -

The Bedouin Population in the Negev

T The Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Bedouins h in the Negev have rarely been included in the Israeli public e discourse, even though they comprise around one-fourth B Bedouin e of the Negev’s population. Recently, however, political, d o economic and social changes have raised public awareness u i of this population group, as have the efforts to resolve the n TThehe BBedouinedouin PPopulationopulation status of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, P Population o primarily through the Goldberg and Prawer Committees. p u These changing trends have exposed major shortcomings l a in information, facts and figures regarding the Arab- t i iinn tthehe NNegevegev o Bedouins in the Negev. The objective of this publication n The Abraham Fund Initiatives is to fill in this missing information and to portray a i in the n Building a Shared Future for Israel’s comprehensive picture of this population group. t Jewish and Arab Citizens h The first section, written by Arik Rudnitzky, describes e The Abraham Fund Initiatives is a non- the social, demographic and economic characteristics of N Negev profit organization that has been working e Bedouin society in the Negev and compares these to the g since 1989 to promote coexistence and Jewish population and the general Arab population in e equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab v Israel. citizens. Named for the common ancestor of both Jews and Arabs, The Abraham In the second section, Dr. Thabet Abu Ras discusses social Fund Initiatives advances a cohesive, and demographic attributes in the context of government secure and just Israeli society by policy toward the Bedouin population with respect to promoting policies based on innovative economics, politics, land and settlement, decisive rulings social models, and by conducting large- of the High Court of Justice concerning the Bedouins and scale social change initiatives, advocacy the new political awakening in Bedouin society. -

My Life Story Malca Flasterstein

My Life Story Malca Flasterstein Josie Raborar, Storykeeper Acknowledgement As we near the consummation of the Ethnic Life Stories Project, there is a flood of memories going back to the concept of the endeavor. The awareness was there that the project would lead to golden treasures. But I never imagined the treasures would overflow the storehouse. With every Story Teller, every Story Keeper, every visionary, every contributor, every reader, the influence and impact of the project has multiplied in riches. The growth continues to spill onward. As its outreach progresses, "boundaries" will continue to move forward into the lives of countless witnesses. Very few of us are "Native Americans." People from around the world, who came seeking freedom and a new life for themselves and their families, have built up our country and communities. We are all individuals, the product of both our genetic makeup and our environment. We are indeed a nation of diversity. Many of us are far removed from our ancestors who left behind the familiar to learn a new language, new customs, new political and social relationships. We take our status as Americans for granted. We sometimes forget to welcome the newcomer. We bypass the opportunity to ask about their origins and their own journey of courage. But, wouldn't it be sad if we all spoke the same language, ate the same food, and there was no cultural diversity. This project has left me with a tremendous debt of gratitude for so many. The almost overwhelming task the Story Keeper has, and the many hours of work and frustration to bring forth a story to be printed. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2005 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► The o rganization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state re porting requirements. A For the 2005 calendar year , or tax year be and B Check If C Name of organization D Employer Identification number applicable Please use IRS change ta Qachange RICA IS RAEL CULTURAL FOUNDATION 13-1664048 E; a11gne ^ci See Number and street (or P 0. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 0jretum specific 1 EAST 42ND STREET 1400 212-557-1600 Instruo retum uons City or town , state or country, and ZIP + 4 F nocounwro memos 0 Cash [X ,camel ded On° EW YORK , NY 10017 (sped ► [l^PP°ca"on pending • Section 501 (Il)c 3 organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations. must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates ? Yes OX No G Website : : / /AICF . WEBNET . ORG/ H(b) If 'Yes ,* enter number of affiliates' N/A J Organization type (deckonIyone) ► [ 501(c) ( 3 ) I (insert no ) ] 4947(a)(1) or L] 527 H(c) Are all affiliates included ? N/A Yes E__1 No Is(ITthis , attach a list) K Check here Q the organization' s gross receipts are normally not The 110- if more than $25 ,000 . -

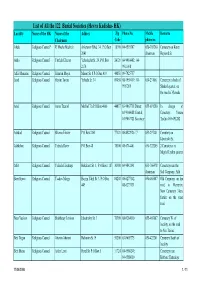

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2009 / 2010

Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2009 / 2010 Maya Choshen, Michal Korach 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Publication No. 402 Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2009/2010 Maya Choshen, Michal Korach This publication was published with the assistance of the Charles H. Revson Foundation, New York The authors alone are responsible for the contents of the publication Translation from Hebrew: Sagir International Translation, Ltd. © 2010, Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies The Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., 92186 Jerusalem [email protected] http://www.jiis.org Table of Contents About the Authors ............................................................................................. 7 Preface ................................................................................................................ 8 Area .................................................................................................................... 9 Population ......................................................................................................... 9 Population size ........................................................................................... 9 Geographical distribution of the population .............................................11 Population growth .................................................................................... 12 Sources of population growth .................................................................. 12 Birth