The Decline of Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robertson Davies Fifth Business Fifth Business Definition: Those Roles Which, Being Neither Those of Hero Nor Heroine, Confidant

Robertson Davies Fifth Business Fifth Business Definition: Those roles which, being neither those of Hero nor Heroine, Confidante nor Villain, but which were nonetheless essential to bring about the Recognition or the denouement, were called the Fifth Business in drama and opera companies organized according to the old style; the player who acted these parts was often referred to as Fifth Business. —Tho. Overskou, Den Daaske Skueplads I. Mrs. Dempster 1 My lifelong involvement with Mrs. Dempster began at 8 o’clock p.m. on the 27th of December, 1908, at which time I was ten years and seven months old. I am able to date the occasion with complete certainty because that afternoon I had been sledding with my lifelong friend and enemy Percy Boyd Staunton, and we had quarrelled, because his fine new Christmas sled would not go as fast as my old one. Snow was never heavy in our part of the world, but this Christmas it had been plentiful enough almost to cover the tallest spears of dried grass in the fields; in such snow his sled with its tall runners and foolish steering apparatus was clumsy and apt to stick, whereas my low-slung old affair would almost have slid on grass without snow. The afternoon had been humiliating for him, and when Percy as humiliated he was vindictive. His parents were rich, his clothes were fine, and his mittens were of skin and came from a store in the city, whereas mine were knitted by my mother; it was manifestly wrong, therefore, that his splendid sled should not go faster than mine, and when such injustice showed itself Percy became cranky. -

English-Spanish (Dictionnaire)

English−spanish (dictionnaire) English−spanish Dictionary éditions eBooksFrance www.ebooksfrance.com English−spanish Dictionary 1 English−spanish (dictionnaire) Adapted from : http://www.freedict.com/dictionary/index. -

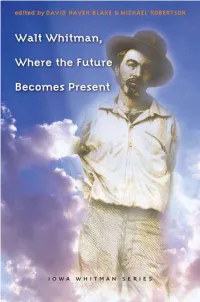

Walt Whitman, Where the Future Becomes Present, Edited by David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson

7ALT7HITMAN 7HERETHE&UTURE "ECOMES0RESENT the iowa whitman series Ed Folsom, series editor WALTWHITMAN WHERETHEFUTURE BECOMESPRESENT EDITEDBYDAVIDHAVENBLAKE ANDMICHAELROBERTSON VOJWFSTJUZPGJPXBQSFTTJPXBDJUZ University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 2008 by the University of Iowa Press www.uiowapress.org All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Richard Hendel No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The University of Iowa Press is a member of Green Press Initiative and is committed to preserving natural resources. Printed on acid-free paper issn: 1556–5610 lccn: 2007936977 isbn-13: 978-1-58729–638-3 (cloth) isbn-10: 1-58729–638-1 (cloth) 08 09 10 11 12 c 5 4 3 2 1 Past and present and future are not disjoined but joined. The greatest poet forms the consistence of what is to be from what has been and is. He drags the dead out of their coffins and stands them again on their feet .... he says to the past, Rise and walk before me that I may realize you. He learns the lesson .... he places himself where the future becomes present. walt whitman Preface to the 1855 Leaves of Grass { contents } Acknowledgments, ix David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson Introduction: Loos’d of Limits and Imaginary Lines, 1 David Lehman The Visionary Whitman, 8 Wai Chee Dimock Epic and Lyric: The Aegean, the Nile, and Whitman, 17 Meredith L. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Interfaith on the Internet

INTERFAITH ON THE INTERNET VIRTUAL REFLECTIONS ON RELIGION COPING WITH CRISIS • THE PERSONAL IS POLITICAL • BORDER & PLACE • PHOTOGRAPHY • SCHOLARSHIP • RITUAL & PRACTICE • ARTS & LITERATURE • EXPERIENCING THE DIVINE Anna Aversa Bryce Couperus Aitan S Maeir Roman Catholicism The Church of Jesus Christ of Judaism Journalism and Religious Studies Latter-day Saints Psychology and Cedarburg, WI Russian Neurobiology (Pre-Med) Mellen, WI Skokie, IL Osama Fattouh Azariah Horowitz Calvin Floyd Islam Judaism Christianity Neurobiology Spanish and French Envr. Studies Madison, WI Milwaukee, WI and History Ann Arbor, MI Milan Stolpman Danielle Wendricks Kally Leidig Roman Catholicism Spirituality Atheism Microbiology, Global Community & Nonprofit Poli Sci, Econ, and Health, and Sustainability Leadership and History Envr. Studies Minneapolis, MN Madison, WI Lino Lakes, MN Grace Landrum Aerin Leigh Lammers Yaseen Najeeb Christianity Reform Judaism Islam Social Work English, Comm Arts, Political Science Green Bay, WI and Poli Sci Milwaukee, WI St. Louis, MO Maya Reinfeldt Amanjot (Amy) Yadev Ethan C. Dickler Russian Orthodoxy Sikhi Roman Catholicism Russian Literature and Neurobiology and Gender & English Literature International Studies Women’s Studies Mineral Point, WI Verona, WI Menomonee Falls, WI Calvin Floyd Jake Henry Laura Alvarez Christianity Judaism Christianity Envr. Studies Microbiology Biological and History Minneapolis, MN Systems Engr Ann Arbor, MI Cali, Colombia Anusha Mehta Mukadas Abdullah Hinduism/Jainism Islam Health Promotion Health -

California Tech Opinion Poll

You1re Congratulations, full-fledged Seniors CaliforniaTech monks at last Associated Students of the Califofl1ia Institute of Technology Volume LXVII. Pasadena, (California, Thursday, May 26, 1966 Number 30 Snake, VR, and TBP Frosh Awards Given at Assembly by Fishbone for his tremendous performances phy for his spirit, teamwork, im Campus personalities present in cross country and track. Fol provement, and attitude. Coach ed honors and awards to House lowing this, Emery presented Mehringer completed the winter and individuals at last Thursday last year's soccer coach Lee An honors with his presentation of evening's Spring Awards Assem drews with a five-stripe sweater the wrestling letter winners. bly at Tournament Park_ for his years of successful serv Lonnie Martin, an outstanding Lloyd led the Houses in hon ice to the soccer team. Finally, all-around frosh athlete, received ors on being presented with the the stUdent body honored Mr. the Alumni Baseball Trophy Goldsworthy Interhouse "Snake" Musselman when Athletic Man from Coach Preisler for his by Dr_ Huttenback and with the ager Craig McAllister presented sportsmanship, moral influence, Discobolus Trophy by IHC Chair him wHh an ASCIT honor key. playing ability, and individual man Eric Young. Coach Nerrie Laureled jocks improvement. Preisler and Coach then presented Page with the Coach Preisler spoke about the Bond also praised the remainder Roving TECH photographer caught these two B&G men slaving away at coveted Interhouse Sports Tro· basketball team, and then hon of the baseball team. their jobs one day last week. phy, while Dabney received the ored Terry Bruns with the Ves Coach Emery awarded the Varsity Rating Trophy from Mr. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Music for Guitar

So Long Marianne Leonard Cohen A Bm Come over to the window, my little darling D A Your letters they all say that you're beside me now I'd like to try to read your palm then why do I feel so alone G D I'm standing on a ledge and your fine spider web I used to think I was some sort of gypsy boy is fastening my ankle to a stone F#m E E4 E E7 before I let you take me home [Chorus] For now I need your hidden love A I'm cold as a new razor blade Now so long, Marianne, You left when I told you I was curious F#m I never said that I was brave It's time that we began E E4 E E7 [Chorus] to laugh and cry E E4 E E7 Oh, you are really such a pretty one and cry and laugh I see you've gone and changed your name again A A4 A And just when I climbed this whole mountainside about it all again to wash my eyelids in the rain [Chorus] Well you know that I love to live with you but you make me forget so very much Oh, your eyes, well, I forget your eyes I forget to pray for the angels your body's at home in every sea and then the angels forget to pray for us How come you gave away your news to everyone that you said was a secret to me [Chorus] We met when we were almost young deep in the green lilac park You held on to me like I was a crucifix as we went kneeling through the dark [Chorus] Stronger Kelly Clarkson Intro: Em C G D Em C G D Em C You heard that I was starting over with someone new You know the bed feels warmer Em C G D G D But told you I was moving on over you Sleeping here alone Em Em C You didn't think that I'd come back You know I dream in colour -

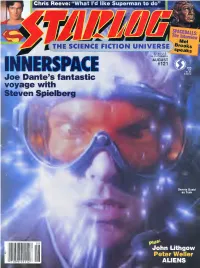

Starlog Magazine Issue

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question