Brexit: the Irish Dimension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Liberties 1/7 (1=Most Free, 7=Least Free)

Ireland | Freedom House Page 1 of 13 Freedom in the World 2018 Ireland Profile FREEDOM Freedom in the World STATUS: Scores Quick Facts FREE Freedom Rating 1/7 Political Rights 1/7 Civil Liberties 1/7 (1=Most Free, 7=Least Free) Aggregate Score: 96/100 (0=Least Free, 100=Most Free) Overview: Ireland is a stable democracy. Political rights and civil liberties are robust, although the government suffers from some incidence of corruption. There is some limited societal discrimination, especially against the traditionally nomadic Irish Travellers. Key Developments in 2017: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2018/ireland 9/21/2018 Ireland | Freedom House Page 2 of 13 • Leo Varadkar—the son of an Indian immigrant, Dàil as the youngest Prime Minister (Taoiseach) ever, following the decision by Enda Kenny to step down after six years. • In July, the Council of Europe criticized the Irish government for failing to uphold its commitments to implementing anticorruption measures. • In March, the country was shocked by the discovery of a mass grave of babies and children at the site of the former Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Galway. The facility had housed orphaned children and the children of unwed mothers, and closed in 1961. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: POLITICAL RIGHTS: 39 / 40 A. ELECTORAL PROCESS: 12 / 12 A1. Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2018/ireland 9/21/2018 Ireland | Freedom House Page 3 of 13 president. Thus, the legitimacy of the prime minister is largely dependent on the conduct of Dàil elections, which historically have free and fair. -

Judging W.T. Cosgrave Free

FREE JUDGING W.T. COSGRAVE PDF Michael Laffan | 340 pages | 22 Nov 2014 | Royal Irish Academy | 9781908996398 | English | Dublin, Ireland History Ireland Jump to navigation. We Judging W.T. Cosgrave scholarship and promote awareness of how science and the humanities enrich our lives and benefit society. We believe that good research needs to be promoted, sustained and communicated. The Academy is run by a Council of its members. Membership is by election and considered the highest academic honour in Ireland. Cosgrave has been neglected by scholars in comparison with Judging W.T. Cosgrave prominent twentieth-century Irish leaders. This biography, by a leading Irish historian, uses sources not previously consulted to examine his career as local politician, rebel, minister, head of government for almost ten years, and opposition leader. In particular, it assesses his role as a state-builder Judging W.T. Cosgrave a key figure in the Irish democratic tradition. Solve our book cover jigsaw puzzle here. Having lectured briefly at the University of East Anglia he took up a post in UCD, where he taught for over three decades and served in various positions, including as head of the School of History and Archives, before retiring in He has lectured widely in Ireland and across the globe. He has published widely on Modern Irish History. The Royal Irish Academy has developed teaching material that Judging W.T. Cosgrave of use in the classroom. Designed to be both stimulating to students and integral to the relevant school curriculum, the goal is to motivate and inspire Judging W.T. Cosgrave, second level and third level students on the island of Ireland. -

Sunday Independent

gjj Dan O'Brien The Irish are becoming EXCLUSIVE ‘I was hoping he’d die,’ Jill / ungovernable. This Section, Page 18Meagher’s husband on her murderer. Page 20 9 6 2 ,0 0 0 READERS Vol. 109 No. 17 CITY FINAL April 27,2014 €2.90 (£1.50 in Northern Ireland) lMELDA¥ 1 1 P 1 g§%g k ■MAY ■ H l f PRINCE PHILIP WAS CHECKING OUT MY ASS LIFE MAGAZINE ALL IS CHANGING, CHANGING UTTERLY. GRAINNE'SJOY ■ Voters w a n t a n ew political p arty Poll: FG gets MICHAEL McDOWELL, Page 24 ■ Public demands more powers for PAC SHANE ROSS, Page 24 it in the neck; ■ Ireland wants Universal Health Insurance -but doesn'tbelieve the Governmentcan deliver BRENDAN O'CONNOR, Page 25 ■ We are deeply suspicious SF rampant; of thecharity sector MAEVE SHEEHAN, Page 25 ■ Royal family are welcome to 1916 celebrations EILISH O'HANLON, Page 25 new partycall LOVE IS IN THE AIR: TV presenter Grainne Seoige and former ■ ie s s a Childers is rugbycoach turned businessman Leon Jordaan celebrating iittn of the capital their engagement yesterday. Grainne's dress is from Havana EOGHAN HARRIS, Page 19 in Donnybrookr Dublin 4. Photo: Gerry Mooney. Hayesfaces defeat in Dublin; Nessa to top Full Story, Page 5 & Living, Page 2 poll; SF set to take seat in each constituency da n ie l Mc Connell former minister Eamon Ryan and JOHN DRENNAN (11 per cent). MillwardBrown Our poll also asked for peo FINE Gael Junior Minister ple’s second preference in Brian Hayes is facing a humil FULL POLL DETAILS AND ANALYSIS: ‘ terms of candidate. -

In-Depth Interview with Minister for Justice Frances Fitzgerald

30 PROFILE law society gazette www.gazette.ie December 2014 Fitz FOR PURPOSE Minister for Justice Frances Fitzgerald speaks to Mark McDermott about her personal goals, the Legal Services Regulation Bill – and the challenges of addressing the ‘severe systemic failings’ Mark McDermott in policing is editor of the Law Society Gazette hen seeking to interview a member of Cabinet, it tends to at a glance become a waiting game. Diary times get ‘hit for six’ when the n On winning and losing in politics Government is dealing with n Her thoughts on being contacted by Enda Kenny hot-potato issues like water to be the new Minister for Justice charges and when you have the chief inspector of the W n The minister’s personal vision for the Irish justice Garda Inspectorate, Robert Olson, trying to beat you to system the door of the office of the Minister for Justice. n Institutional reform, transparency and Once finally through the door, Minister Fitzgerald accountability comes across as extremely friendly and focused, to the n The Legal Services Regulation Bill – its strengths point that her attention remains fully fixed on you, and weaknesses regardless of all other distractions. She speaks of having n Dealing with the breakdown in policing practices had “quite a chequered career” in politics: “You know, you win some, you lose some. You survive in it, you don’t survive in it. When I look at the number of people I’ve known who’ve had very short stays in the Dáil and the Senate, and for me to have had the opportunity to be in the Cabinet and to be a minister in two important but associated with the legal area – for probably 30 years portfolios, it is, really, a great opportunity. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2016 Remarks at the Congressional

Administration of Barack Obama, 2016 Remarks at the Congressional Friends of Ireland Luncheon March 15, 2016 President Obama. Speaker Ryan, Members of Congress, thank you so much for having me here today. Taoiseach and Mrs. Kenny, leaders of Ireland and Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom, honored guests: It is always a privilege to join you for this wonderful St. Patrick's Day celebration. And with names like Obama, Biden, Ryan, and McConnell, you can rest assured that the old sod's stranglehold on power in Washington is as strong as ever. [Laughter] Now, it's true that it's not technically St. Patrick's Day, but that's okay. Most folks who celebrate it aren't Irish either. [Laughter] I can talk about them because I am Irish, as I have been prone to mention on this occasion. [Laughter] Back in 2008, the Corrigan Brothers even penned a song called "There is No One as Irish as Barack Obama." [Laughter] This is true. As the lyrics go: "From Kerry to Cork, let's hear it for Barack from old Moneygall." And somehow, that line did not result in cries for my birth certificate on the campaign trail. [Laughter] Now, to paraphrase something President Reagan once said at this lunch, on St. Patrick's Day, you should spend time with saints and scholars. So the Taoiseach and I have two more stops to make after this. [Laughter] But we do enjoy this tradition. And I want to thank Speaker Ryan for continuing it. It's a welcome break from politics as usual, a moment when we all trade in our red and power blue ties for our green ones. -

OECD Observer Crossword

Ireland’s recovery, by Enda Kenny How inequality hurts growth New evidence on productivity and the environment Digital finance and education Europe’s migration flows No 301 Q4 2014 www.oecdobserver.org STOP PRESS Paris attacks: Tributes The challenge ahead CONTENTS No 301 Q4 2014 TRIBUTES AND REACTIONS SOCIETY 2 In the wake of the Paris attacks, January 2015 16 Digital learning in schools Francesco Avvisati EDITORIALS 18 Migration and jobs: Is Europe’s labour 3 Building the conditions of a safer world market adjusting? Angel Gurría, Secretary-General of the OECD Thomas Liebig 4 Ireland: On the path to recovery Enda Kenny, Taoiseach (Prime Minister), BOOKS Ireland: On the path to recovery, page 4 Ireland 19 Review: Making city ports competitive NEWS BRIEF ECONOMIC OUTLOOK 6 Inequality hurts growth; Tax revenues rise; Soundbites; Economy; Country roundup; 21 Shifting into higher gear and rebuilding the Bribery exposed; Steel warnings; Plus engines of growth ça change Catherine Mann, OECD Chief Economist 23-35 Country snapshots ECONOMY 9 Environmental policies don’t have to hurt OECD.ORG Philanthropy, digital payments and fi nancial inclusion, productivity 37 Jean Tirole: An appreciation page 13 11 A sharing economy Patrick Lenain, OECD Economics Department Interview: Frederic Mazzella, Founder and 38 French minister Taubira attacks bribery; CEO of BlaBlaCar Visits 12 Is inequality good or bad for growth? 39 Recent speeches by Angel Gurría; List of 13 Philanthropy, digital payments and OECD ambassadors fi nancial inclusion 40 Calendar; Frankie.org -

Ireland in Brief in Ireland .Ie Céad Míle Fáilte Reddog Design Www

Ireland in Brief .ie Céad Míle Fáilte reddog design_www. Ireland in Brief A general overview of Ireland’s political, economic and cultural life Iveagh House, headquarters of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Dublin. Map of Ireland overleaf www.dfat.ie Ireland in Brief .ie Céad Míle Fáilte reddog design_www. Ireland in Brief A general overview of Ireland’s political, economic and cultural life Iveagh House, headquarters of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Dublin. Map of Ireland overleaf www.dfat.ie Photo credits 2 Fernando Carniel Machado / Thinkstock 4 Houses of the Oireachtas 7 CAPT Vincenzo Schettini / Department of Defence 8 © National Museum of Ireland 15 Paul Rowe / Educate Together 18 Trinity College Dublin 19 Dublin Port Company 20 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 24 RTE / John Cooney 27 Maxwells 28 Irish Medical News 33 Press Association 35 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 36 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 38 Department of the Taoiseach 39 Irish Aid 41 Department of the Taoiseach 42 Collection Irish Museum of Modern Art, Donation Gordon Lambert Trust, 1992. 45 © John Minehan 46 © National Gallery of Ireland 49 Denis Gilbert 50 Colm Hogan 51 Irish Film Board 52 Irish Film Board 54 Sportsfile / Stephen McCarthy 55 Sportsfile / Brian Lawless 56 Sportsfile / David Maher Ordnance Survey Ireland Permit No. 8670 © Ireland/Government of Contents This booklet provides a general overview of Ireland’s political, economic and cultural life. While it is not possible to include every aspect of life in Ireland in this short publication, we hope that you will discover a little about Ireland and its people. -

Final DBL Text

38 Days of blue loyalty internally and was in a weak position in the party system. Even his most dogged critics within the party invariably paid tribute to his integrity and decency, and most of them acknowledged that, however much responsibility Bruton bore for the party’s uninspiring record during the 1990s, many other factors had also played a part. Bruton’s defenders argued that the heave against him epitomised the way the political process was becoming trivialised, with integrity seen as only a minor counterbalance to the apparently more important factor of a dis- appointing opinion poll result. Those outside the party, and some within it, also pointed to a patchy performance by the party’s spokespersons on various policy areas. Any realistic evaluation of Bruton’s leadership has to take full account of the difficulty of making an impact as the leader of a party in opposition, at a time when there was little to choose between the policies of the various alternative governments and when the country was enjoying unprecedented levels of eco- nomic growth. He was party leader for over 10 years, which is by no means a bad tenure given the demands on politicians. If he was not able to inspire very much enthusiasm among the electorate, or transform the fortunes of his party, it has to be acknowledged that he is not the only party leader about whom this has been said. Once Bruton had lost the confidence motion, the race began for the vote to fill the vacancy. The bookmakers offered prices about eight possible runners, but the odds for Michael Noonan (5 to 2 on) made it clear that the race was not per- ceived as wide open. -

Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 2021 Programme Contents

Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 2021 Programme Contents Foreword from the Minister for Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media 3 Context from the Chair of the Expert Advisory Group (EAG) on Centenary Commemorations 4 Decade of Centenaries Programme 2021 5 Objectives of the Programme 6 Themes under the Programme 7 Strands of the Programme 8 STATE CEREMONIAL STRAND 9 HISTORICAL STRAND 10 COMMUNITY STRAND 27 CREATIVE IMAGINATION STRAND 38 Key contacts and resources 45 click here on each image in the Programme for caption/credit information’ | Page 2 Foreword I am very pleased to present The State’s role is to set a measured, inclusive and The commemorative programme for 2021 the Decade of Centenaries sensitive tone; to faithfully present our history, is supported with a budget of €5 million – a Programme for 2021. even when the historical record is distressing. significant increase of €3 million on last year’s We must also reflect on the great tragedy of all of funding allocation. those who died or whose lives were transformed We have, as all readers will be acutely The programme acknowledges both the because of the events that took place during those aware, now entered the most challenging military aspects as well as the constitutional years. and sensitive period of commemoration, parliamentary traditions and the democratic which includes the Struggle for Historical accuracy, academic integrity, and processes underpinning all traditions on this Independence, Partition, the Foundation archival discovery are key tenets of the island. It explores the social, cultural, and of the State and the Civil War. My commemorative programme, which follows closely economic changes that were taking place during responsibility, as Minister for Tourism, the centenary timeline of the events that occurred this period. -

Dáil Éireann

Vol. 959 Thursday, No. 8 5 October 2017 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DÁIL ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Insert Date Here 05/10/2017A00050Business of Dáil � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 879 05/10/2017B00400Death of Former Taoiseach: Expressions of Sympathy � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 879 DÁIL ÉIREANN Déardaoin, 5 Deireadh Fómhair 2017 Thursday, 5 October 2017 Chuaigh an Ceann Comhairle i gceannas ar 12 p�m� Paidir. Prayer. 05/10/2017A00050Business of Dáil 05/10/2017A00075An Ceann Comhairle: The Minister of State, Deputy Joe McHugh, has a business proposal to put to the House� 05/10/2017A00087Minister of State at the Department of the Taoiseach (Deputy Joe McHugh): Expres- sions of sympathy on the death of former Taoiseach, Liam Cosgrave, will be taken now and on the conclusion of expressions of sympathy, the Dáil shall adjourn forthwith until 1 p�m� on Tuesday, 10 October 2017� 05/10/2017A00093An Ceann Comhairle: Is that agreed? Agreed� 05/10/2017B00400Death of Former Taoiseach: Expressions of Sympathy 05/10/2017B00500The Taoiseach: I was deeply saddened to hear of the death of an t-iarThaoiseach and for- mer Member of this House, Liam Cosgrave� As Taoiseach and leader of Fine Gael, I extend my deepest sympathy to his family and friends� Liam Cosgrave was someone who devoted his life to public service� Today a grateful country thanks and -

How Ireland Voted 2007 This Page Intentionally Left Blank How Ireland Voted 2007: the Full Story of Ireland’S General Election

How Ireland Voted 2007 This page intentionally left blank How Ireland Voted 2007: The Full Story of Ireland’s General Election Edited by Michael Gallagher Michael Marsh palgrave macmillan Editorial Matter and Selection © Michael Gallagher and Michael Marsh 2008 Chapters 1–13 and Appendices © Palgrave Macmillan Ltd 2008 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2008 978-0-230-50038-9 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their right to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2008 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St Martin’s Press LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-0-230-20198-9 paperback ISBN 978-0-230-20198-9 ISBN 978-0-230-59799-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230597990 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

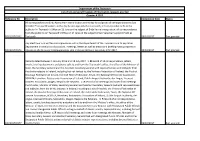

Reference No Description Completion Date Status FOI/2017/0142 All

Department of the Taoiseach List of non-personal Freedom of Information requests granted Quarter 4 2017 Reference No Description Completion Date Status All correspondence to Enda Kenny from world leaders on the day he resigned; all correspondence to Leo Varadkar from world leaders on the day he was appointed as Taoiseach; all correspondence from the public to An Taoiseach's Office on 13 June on the subject of Enda Kenny's resignation; a ll correspondence from the public to An Taoiseach's Office on 14 June on the subject of Leo Varadkar's appointment as FOI/2017/0142 Taoiseach. 06/10/2017 Part granted Any electronic and written correspondence within the Department of the Taoiseach and to any other Department in relation to discussions, meetings, letters as well as emails and briefing notes prepared in FOI/2017/0175 relation to the Strategic Communications Unit in the period June 1st to July 17th 2017. 09/10/2017 Part granted Records dated between 1 January 2016 and 18 July 2017. 1. A record of all correspondence, letters, emails, briefing documents and phone calls to and from the Taoiseach’s office, the office of the Minister of State, the Secretary General and the Assistant Secretary General with representatives and lobbyists from the drinks industry in Ireland, including but not limited to; the Vintners Federation of Ireland, the Alcohol Beverage Federation of Ireland, the Irish Hotels Federation, Tesco, the National Off-Licence Association, RGDATA, Heineken, Restaurants Association of Ireland, Dublin Airport Authority, Aer Lingus, Licensed