English Suites BWV806-811

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J. S. BACH English Suites Nos

J. S. BACH English Suites Nos. 4–6 Arranged for Two Guitars Montenegrin Guitar Duo Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) with elegantly broken chords. This is interrupted by a The contrasting pair of Gavottes with a perky walking bass English Suites Nos. 4–6, BWV 809–811 sudden burst of semiquavers leading to a moment’s accompaniment brings in the atmosphere of a pastoral reflection before plunging into an extended and brilliant dance in the market square. The second Gavotte evokes (Arranged for two guitars by the Montenegrin Guitar Duo) fugal Allegro. Of the Préludes in the English Suites this is images of wind instruments piping together in rustic chorus. The English Suites is the title given to a set of six suites for Bach scholar, David Schulenberg has observed that while the longest and most elaborate. The Allemande which The Gigue, in 12/16 metre, is virtuosic in both keyboard believed to have been composed between 1720 the beginning of the Gigue presents a normal three-part follows is, in comparison, an oasis of calm, with superb compositional aspects and the technical demands on the and the early 1730s. During this period, Bach also explored fugal exposition, from then on, no more than two voices are contrapuntal writing and ingenious tonal modulations. The performers. Bach’s incomparable art of fugal writing is at the suite form in the six French Suites and the seven large heard at a time. Courante unites a French-style melodic line with a full stretch here, the second half representing, as in mirror suites under the title of Partitas (six in all) and an English Suite No. -

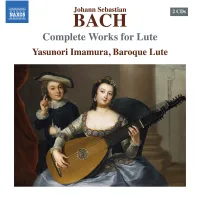

Imamura-Y-S03c[Naxos-2CD-Booklet

573936-37 bk Bach EU.qxp_573936-37 bk Bach 27/06/2018 11:00 Page 2 CD 1 63:49 CD 2 53:15 CD 2 Arioso from St John Passion, BWV 245 1Partita in E major, BWV 1006a 20:41 1Suite in E minor, BWV 996 18:18 # # Prelude 2:51 Consider, O my soul 2 Prelude 4:13 2 Betrachte, meine Seel’ Allemande 3:02 3 Loure 3:58 3 Betrachte, meine Seel’, mit ängstlichem Vergnügen, Consider, O my soul, with fearful joy, consider, Courante 2:40 4 Gavotte en Rondeau 3:29 4 Mit bittrer Lust und halb beklemmtem Herzen in the bitter anguish of thy heart’s affliction, Sarabande 4:24 5 Menuet I & II 4:43 5 Dein höchstes Gut in Jesu Schmerzen, thy highest good is Jesus’ sorrow. Bourrée 1:33 6 Bourrée 1:51 6 Wie dir auf Dornen, so ihn stechen, For thee, from the thorns that pierce Him, Gigue 2:27 Gigue 3:48 Die Himmelsschlüsselblumen blühn! what heavenly flowers spring. Du kannst viel süße Frucht von seiner Wermut brechen Thou canst the sweetest fruit from his wormwood gather, 7Suite in C minor, BWV 997 22:01 7Suite in G minor, BWV 995 25:15 Drum sieh ohn Unterlass auf ihn! then look on Him for evermore. Prelude 6:11 8 Prelude 3:11 8 Allemande 6:18 9 Fugue 7:13 9 Sarabande 5:28 0 Courante 2:35 Recitativo from St Matthew Passion, BWV 244b 0 $ $ Gigue & Double 6:09 ! Sarabande 2:50 Gavotte I & II 4:43 Ja freilich will in uns Yes! Willingly will we ! @ Prelude in C minor, BWV 999 1:55 Gigue 2:38 Ja freilich will in uns das Fleisch und Blut Yes! Willingly will we, Flesh and blood, Zum Kreuz gezwungen sein; Be brought to the cross; @ Fugue in G minor, BWV 1000 5:46 #Arioso from St John Passion, BWV 245 2:24 Je mehr es unsrer Seele gut, The harsher the pain Arioso: Betrachte, meine Seel’ Je herber geht es ein. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

Southern California Junior Bach Festival

The SCJBF 3 year, cyclical repertoire list for the Complete Works Audition Students may enter the Complete Works Audition (CWA) only once each year as a soloist on the same instrument and must perform the same music in the same category that they performed at the Branch and Regional Festivals, but complete as indicated on this list. Students will be disqualified if photocopied music is presented to the judges or used by accompanists (with the exception of facilitating page turns). Note: Repertoire lists for years in parentheses are not finalized and are subject to change Category I – SHORT PRELUDES AND FUGUES Year Composition BWV Each year Select any two of the following: Preludes: BWV 924-943 and 999 Fugues: BWV 952, 953 and 961 Select one of the following: 1. Prelude and Fugue in a m 895 2. Prelude and Fughetta in d m 899 3. Prelude and Fugue in e m 900 4. Prelude and Fughetta in G M 902 Category II – VARIOUS DANCE MOVEMENTS The dance movements listed below – from one of the listed Suites or Partitas – are required for the Complete Works Audition. Year Composition BWV 2021 English Suites: 1. From the A Major #1 806 The Bourree I and the Bourree II 2. From the e minor #5 810 The Passepied I and the Passepied II French Suites: 1. From the d minor #1 812 The Menuet I and the Menuet II 2. From the G Major #5 816 The Gavotte, Bourree and Loure Partitas: 1. From the a min or #3 827 The Burlesca and the Scherzo 2. -

Alumnews2007

C o l l e g e o f L e t t e r s & S c i e n c e U n i v e r s i t y D EPARTMENT o f o f C a l i f o r n i a B e r k e l e y MUSIC IN THIS ISSUE Alumni Newsletter S e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 7 1–2 Special Occasions Special Occasions CELEBRATIONS 2–4 Events, Visitors, Alumni n November 8, 2006, the department honored emeritus professor Andrew Imbrie in the year of his 85th birthday 4 Faculty Awards Owith a noon concert in Hertz Hall. Alumna Rae Imamura and world-famous Japanese pianist Aki Takahashi performed pieces by Imbrie, including the world premiere of a solo piano piece that 5–6 Faculty Update he wrote for his son, as well as compositions by former Imbrie Aki Takahashi performss in Hertz Hall student, alumna Hi Kyung Kim (professor of music at UC Santa to honor Andrew Imbrie. 7 Striggio Mass of 1567 Cruz), and composers Toru Takemitsu and Michio Mamiya, with whom Imbrie connected in “his Japan years.” The concert was followed by a lunch in Imbrie’s honor in Hertz Hall’s Green Room. 7–8 Retirements Andrew Imbrie was a distinguished and award-winning member of the Berkeley faculty from 1949 until his retirement in 1991. His works include five string quartets, three symphonies, numerous concerti, many works for chamber ensembles, solo instruments, piano, and chorus. His opera Angle of 8–9 In Memoriam Repose, based on Wallace Stegner’s book, was premeiered by the San Francisco Opera in 1976. -

Charles Dieupart Ruth Wilkinson Linda Kent PREMIER RECORDING

Music for the Countess of Sandwich Six Suites for Flûte du Voix and Harpsichord Charles Dieupart Ruth Wilkinson Linda Kent PREMIER RECORDING A rare opportunity to experience the unusual, haunting colours of the “voice flute”. Includes two suites copied by J.S. Bach. First release of the Linda Kent Ruth Wilkinson complete suites of Charles Dieupart. Six Suites for Flûte du Voix and Harpsichord (1701) by Charles Dieupart Music for the Countess of Sandwich P 1995 MOVE RECORDS Suitte 1 A major (13’35”) Suitte 4 e minor (12’23”) AUSTRALIA Siutte 2 D major (10’10”) Suitte 3 b minor (12’44”) Suitte 6 f minor (13’46”) Suitte 5 F major (14’19”) move.com.au harles Dieupart was of the 17th century for her health: a French violinist, it was possible that she became C harpsichordist and Dieupart’s harpsichord pupil composer who spent the last before returning to England. 40 years of his life in England. Two versions of the Suites He was known as Charles to his were published simultaneously contemporaries in England but about his final years. One story in Amsterdam by Estienne there is some evidence from letters claimed that Dieupart was on the Roger: one for solo harpsichord signed by Dieupart that he was known brink of going to the Indies to follow and the other with separate parts as Francois in his native France. He a surgeon who proposed using music for violin or flute with a continuo was active in the operatic world: as an anaesthetic for lithotomies. part for bass viol or theorbo and we learn from Sir John Hawkins Hawkins gives us the following figured bass. -

GOLDBERG VARIATIONS - English Suite No

BHP 901 - BACH: GOLDBERG VARIATIONS - English Suite No. 5 in e - Millicent Silver, Harpsichord _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ This disc, the first in our Heritage Performances Series, celebrates the career and the artistry of Millicent Silver, who for some forty years was well-known as a regular performer in London and on BBC Radio both as soloist and as harpsichordist with the London Harpsichord Ensemble which she founded with her husband John Francis. Though she made very few recordings, we are delighted to preserve this recording of the Goldberg Variations for its musical integrity, its warmth, and particularly the use of tonal dynamics (adding or subtracting of 4’ and 16’ stops to the basic 8’) which enhances the dramatic architecture. Millicent Irene Silver was born in South London on 17 November 1905. Her father, Alfred Silver, had been a boy chorister at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor where his singing attracted the attention of Queen Victoria, who had him give special performances for her. He earned his living playing the violin and oboe. His wife Amelia was an accomplished and busy piano teacher. Millicent was the second of their four children, and her musical talent became evident in time-honoured fashion when she was discovered at the age of three picking out on the family’s piano the tunes she had heard her elder brother practising. Eventually Millicent Silver won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London where, as was more common in those days, she studied equally both piano and violin. She was awarded the Chappell Silver Medal for piano playing and, in 1928, the College’s Tagore Gold Medal for the best student of her year. -

The Harpsichord: a Research and Information Guide

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository THE HARPSICHORD: A RESEARCH AND INFORMATION GUIDE BY SONIA M. LEE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch, Chair and Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus Donald W. Krummel, Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus John W. Hill Associate Professor Emerita Heidi Von Gunden ABSTRACT This study is an annotated bibliography of selected literature on harpsichord studies published before 2011. It is intended to serve as a guide and as a reference manual for anyone researching the harpsichord or harpsichord related topics, including harpsichord making and maintenance, historical and contemporary harpsichord repertoire, as well as performance practice. This guide is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather to provide a user-friendly resource on the subject. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation advisers Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch and Professor Donald W. Krummel for their tremendous help on this project. My gratitude also goes to the other members of my committee, Professor John W. Hill and Professor Heidi Von Gunden, who shared with me their knowledge and wisdom. I am extremely thankful to the librarians and staff of the University of Illinois Library System for assisting me in obtaining obscure and rare publications from numerous libraries and archives throughout the United States and abroad. -

Bach and Schumann As Keyboard Pedagogues: a Comparative and Critical Overview of The

Bach and Schumann as Keyboard Pedagogues: A Comparative and Critical Overview of the “Notebook of Anna Magdalena,” and the “Album for the Young.” Esther M. Joh A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Craig Sheppard, Chair Steven J. Morrison Ronald Patterson Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2013 Esther M. Joh University of Washington Abstract Bach and Schumann as Keyboard Pedagogues: A Comparative and Critical Overview of the “Notebook of Anna Magdalena,” and the “Album for the Young.” Esther M. Joh Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Craig Sheppard School of Music This dissertation compares and critically evaluates the keyboard pedagogies and teaching philosophies of J.S. Bach and Robert Schumann as expressed in their important collections intended for young, beginning students—Notebook for Anna Magdalena and Album for the Young, Op. 68, respectively. The terms Method or Method Book will be used throughout in their 18th and 19th centuries’ context. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................................. ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ......................................................................................................... iii CONTENTS ONE. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1 TWO. BACH AND SCHUMANN AS PEDAGOGUES -

J. S. Bach's English and French Suites with an Emphasis on the Courante

J. S. Bach’s English and French Suites with an emphasis on the Courante Renate McLaughlin Introduction Religious confl icts brought about the Figure 1. The Courante from French Suite #1, BWV 812 Thirty Years War (1618–1648), which devastated Germany. Reconstruction took at least one hundred years,1 en- compassing the entire lifetime of Bach. The Treaty of Westphalia (1648), which ended the war, gave each sovereign of the over 300 principalities, which make up modern Germany, the right to deter- mine the religion of the area under his (yes, they were all male) control. This resulted in a cultural competition among the numerous sovereigns, and it also led to the importing of French culture and its imitation (recall that Louis XIV, the “Sun King,” reigned from 1643 to 1715). social standing during his entire career!). French Suites and English Suites the importance of these suites in stu- Bach encountered French language, An elite group of professional musicians In the Baroque era, a suite consisted dents’ progress from the Inventions to music, dance, and theater throughout his stood at his disposal,6 and his duties fo- of a collection of dance tunes linked by the Well-Tempered Clavier. formative years. In the cities where Bach cused on secular chamber music. Since the same key and often with some com- (5) Writing in 2000, Christoph Wolff lived, he would have heard frequent per- the court belonged to the reformed mon thematic material. Concerning the stated as a fact that the “so-called” Eng- formances of minuets, gavottes, couran- church, Bach’s employer expected nei- origin of the suite, Bach scholar Albert lish Suites originated in Bach’s later Wei- tes, sarabandes, etc.2 ther liturgical music nor organ music. -

Doblinger, 1975. OS1 ALB Albrechtsberger, Johann Georg,8 Kleine 1736-1809

OS1 ALB Albrechtsberger, Johann Georg,5 Praeludien 1736-1809. für Orgel / Wien : Doblinger, 1975. OS1 ALB Albrechtsberger, Johann Georg,8 kleine 1736-1809. Praeludien : für Orgel / Wien : Doblinger, c1975. OS1 ARN Arnold, Samuel, 1740-1802.Six overtures for the harpsichord or piano forte, opera VIII / New York : Performers' Facsimiles, [1992] OS1 BAC Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel,Preludium 1714-1788, and composer. six sonatas = (Preludium en zes sonates) / Hilversum, Holland : Internationale Muziekuitgeverij Harmonia-Uitgave, [between 1950 and 1959?] OS1 BAC Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel,Organ 1714-1788. works / Los Altos, Calif. : Packard Humanities Institute, 2008 OS1 BAC Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel,Sonaten 1714-1788. für Orgel = Organ sonatas / Wien : Wiener Urtext Edition, c1995 OS1 BAC Bach, Johann Sebastian, 1685-1750,Orgelwerke composer. = Organ works / Kassel ; Basel ; London : Bärenreiter, 1958-1984. OS1 BAC Bach, Johann Sebastian, 1685-1750,Das wohltemperierte composer. Klavier = The well-tempered clavier / Kassel ; Basel ; London : Bärenreiter, [1989?-1996?] OS1 BAC Bach, Johann Sebastian, 1685-1750,Choralpartiten composer. ; einzeln überlieferte Choralbearbeitungen A-G = Chorale partitas ; individually tra Wiesbaden : Breitkopf & Härtel, [2018] OS1 BAC Bach, Johann Sebastian, 1685-1750,Die sechs Französischencomposer. Suiten : BWV 812-817 : ältere Fassung (A) und jüngere Fassung (B) mit VerKassel ; Basel ; London : Bärenreiter, [1980?] OS1 BAC Bach, Johann Sebastian, 1685-1750,Einzeln überlieferte composer. Choralbearbeitungen H-Z = Individually transmitted organ chorales H-Z / Wiesbaden : Breitkopf & Härtel, [2018] OS1 BAC Bach, Johann Sebastian, 1685-1750,Fantasien composer.; Fugen = Fantasias ; Fugues / Wiesbaden : Breitkopf & Härtel, [2016] OS1 BAC Bach, Johann Sebastian, 1685-1750,Inventionen composer. und Sinfonien = Inventions and symphonies / Kassel ; Basel ; London : Bärenreiter, [1972?] OS1 BAC Bach, Johann Sebastian, 1685-1750,Orgelchoräle composer. -

Guest Artist: Susan Toman, Harpsichord Susan Toman

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-3-2009 Guest Artist: Susan Toman, harpsichord Susan Toman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Toman, Susan, "Guest Artist: Susan Toman, harpsichord" (2009). All Concert & Recital Programs. 4591. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/4591 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. VISITING ARTISTS SERIES 2008-9 Susan Toman, harpsichord Robert A. Iger Lecture Hall Friday, April 3, 2009 8:15 p.m. f1 ,."..,···. PROGRAM Six suittes de clavessin, 1700 Charles Dieupart Cinquieme suite (c.1667-1740 Ouverture . Allemande Courante Sarabande Gavotte Gigue Suite No. 2 in D Georg Bohm Chaconne (1661-1733) Sonata ind, BWV 964 Johann~ Sebastian Bach Adagio (1685-17 50) Allegro Andante Allegro Puga in C Johann Pachelbel (1653-1706) Musicalische Vorstellung Johann Kuhnau einiger biblischer Historien, 1700 (1660-1722) Sonata quarta: The mortally ill then restored Hezekiah Il lament di Hiskia La di lui confidenza in Iddio L'allegrezza del Re convalescente Praludium, Johann Sebastian Bach Fuge und Allegro Es-Dur filr Laute oder Cembalo, BWV 998 To receive occasional emails from the School of Music about upcoming concerts, send an email with your name and address to: [email protected] Canadian harpsichordist Susan Toman holds this year's fourth prize from the Brugge International Harpsichord Competition. She has been featured at.the Bloomington Early Music Festival, the London Early Music Festival, and is the harpsichordist with Montreal-based ensembles Tarantella and Dionysos, the latter of which won • second prize at the 2007 Montreal.Baroque Competition.