Oral History Interview with Ivan C. Karp, 1969 March 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andy Warhol Who Later Became the Most

Jill Crotty FSEM Warhol: The Businessman and the Artist At the start of the 1960s Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg were the kings of the emerging Pop Art era. These artists transformed ordinary items of American culture into famous pieces of art. Despite their significant contributions to this time period, it was Andy Warhol who later became the most recognizable icon of the Pop Art Era. By the mid sixties Lichtenstein, Oldenburg and Rauschenberg each had their own niche in the Pop Art market, unlike Warhol who was still struggling to make sales. At one point it was up to Ivan Karp, his dealer, to “keep moving things moving forward until the artist found representation whether with Castelli or another gallery.” 1Meanwhile Lichtenstein became known for his painted comics, Oldenburg made sculptures of mass produced food and Rauschenberg did combines (mixtures of everyday three dimensional objects) and gestural paintings. 2 These pieces were marketable because of consumer desire, public recognition and aesthetic value. In later years Warhol’s most well known works such as Turquoise Marilyn (1964) contained all of these aspects. Some marketable factors were his silk screening technique, his choice of known subjects, his willingness to adapt his work, his self promotion, and his connection to art dealers. However, which factor of Warhol’s was the most marketable is heavily debated. I believe Warhol’s use of silk screening, well known subjects, and self 1 Polsky, R. (2011). The Art Prophets. (p. 15). New York: Other Press New York. 2 Schwendener, Martha. (2012) "Reinventing Venus And a Lying Puppet." New York Times, April 15. -

Ben Heller, Pioneering Collector of Abstract Expressionism: ‘There’S Nobody Else in That League’

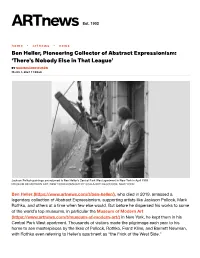

Est. 1902 home • ar tnews • news Ben Heller, Pioneering Collector of Abstract Expressionism: ‘There’s Nobody Else in That League’ BY MAXIMILÍANO DURÓN March 3, 2021 11:00am Jackson Pollock paintings are returned to Ben Heller's Central Park West apartment in New York in April 1959. MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK/LICENSED BY SCALA/ART RESOURCE, NEW YORK Ben Heller (https://www.artnews.com/t/ben-heller/), who died in 2019, amassed a legendary collection of Abstract Expressionism, supporting artists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and others at a time when few else would. But before he dispersed his works to some of the world’s top museums, in particular the Museum of Modern Art (https://www.artnews.com/t/museum-of-modern-art/) in New York, he kept them in his Central Park West apartment. Thousands of visitors made the pilgrimage each year to his home to see masterpieces by the likes of Pollock, Rothko, Franz Kline, and Barnett Newman, with Rothko even referring to Heller’s apartment as “the Frick of the West Side.” When he began seriously collecting Abstract Expressionism during the ’50s, museums like MoMA largely ignored the movement. Heller rushed in headlong. “He wasn’t someone to say, ‘Let me take a gamble on this small picture so that I don’t really commit myself.’ He committed himself a thousand percent, which is what he believed the artists were doing,” Ann Temkin, chief curator of painting and sculpture at MoMA, said in an interview. Though Heller was never formally a board member at MoMA—“I was neither WASP-y enough nor wealthy enough,” he once recalled—he transformed the museum, all the while maintaining close relationships with artists and curators in its circle. -

The New American Art Lily Rothman Oct 09, 2017

The Oct. 13, 1967, cover of TIME TIME MEDIA 50 Years Ago This Week: The New American Art Lily Rothman Oct 09, 2017 Milestone moments do not a year make. Often, it’s the smaller news stories that add up, gradually, to big history. With that in mind, in 2017 TIME History will revisit the entire year of 1967, week by week, as it was reported in the pages of TIME. Catch up on last week’s installment here. Week 41: Oct. 13, 1967 Tony Smith was the "most dynamic, versatile and talented new sculptor in the U.S. art world" proclaimed this week's cover story — but that wasn't the only reason why his work was so newsworthy. The other factor worth considering was what his work at the time looked like. Smoke, the work discussed at the top of the article, was metal, crafted in a fabrication shop from his designs, and it was huge. Smith was TIME's way of looking at a major new trend in contemporary art. As American cities grew and modernized, they needed art that could hold its own. Enter the new American artist: In the year 1967, the styles and statements of America's brash, brilliant and often infuriating contemporary artists have not only become available to the man in the street, but are virtually unavoidable. And with proliferation comes confusion. Whole new schools of painting seem to charge through the art scene with the speed of an express train, causing Pop Artist Andy Warhol to predict the day "when everyone will be famous for 15 minutes." ...Tony Smith, who was thought of as primarily an architect at the time, witnessed the coming of age of the U.S. -

The Painted Word a Bantam Book / Published by Arrangement with Farrar, Straus & Giroux

This edition contains the complete text of the original hardcover edition. NOT ONE WORD HAS BEEN OMITTED. The Painted Word A Bantam Book / published by arrangement with Farrar, Straus & Giroux PUBLISHING HISTORY Farrar, Straus & Giroux hardcover edition published in June 1975 Published entirely by Harper’s Magazine in April 1975 Excerpts appeared in the Washington Star News in June 1975 The Painted Word and in the Booh Digest in September 1975 Bantam mass market edition / June 1976 Bantam trade paperback edition / October 1999 All rights reserved. Copyright © 1975 by Tom Wolfe. Cover design copyright © 1999 by Belina Huey and Susan Mitchell. Book design by Glen Edelstein. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-8978. No part o f this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information address: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 19 Union Square West, New York, New York 10003. ISBN 0-553-38065-6 Published simultaneously in the United States and Canada Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, a division of Random House, Inc. Its trademark, consisting of the words “Bantam Books” and the portrayal of a rooster, is Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada. Bantam Books, New York, New York. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BVG 10 9 I The Painted Word PEOPLE DON’T READ THE MORNING NEWSPAPER, MAR- shall McLuhan once said, they slip into it like a warm bath. -

Hold Still: Looking at Photorealism RICHARD KALINA

Hold Still: Looking at Photorealism RICHARD KALINA 11 From Lens to Eye to Hand: Photorealism 1969 to Today presents nearly fifty years of paintings and watercolors by key Photorealist taken care of by projecting and tracing a photograph on the canvas, and the actual painting consists of varying degrees (depending artists, and provides an opportunity to reexamine the movement’s methodology and underlying structure. Although Photorealism on the artist) of standard under- and overpainting, using the photograph as a color reference. The abundance of detail and incident, can certainly be seen in connection to the history, style, and semiotics of modern representational painting (and to a lesser extent while reinforcing the impression of demanding skill, actually makes things easier for the artist. Lots of small things yield interesting late-twentieth-century art photography), it is worth noting that those ties are scarcely referred to in the work itself. Photorealism is textures—details reinforce neighboring details and cancel out technical problems. It is the larger, less inflected areas (like skies) that contained, compressed, and seamless, intent on the creation of an ostensibly logical, self-evident reality, a visual text that relates are more trouble, and where the most skilled practitioners shine. almost entirely to its own premises: the stressed interplay between the depiction of a slice of unremarkable three-dimensional reality While the majority of Photorealist paintings look extremely dense and seem similarly constructed from the ground up, that similarity is and the meticulous hand-painted reproduction of a two-dimensional photograph. Each Photorealist painting is a single, unambiguous, most evident either at a normal viewing distance, where the image snaps together, or in the reducing glass of photographic reproduction. -

191 Figure 1. Elaine De Kooning, Black Mountain #16, 1948. Private Collection

Figure 1. Elaine de Kooning, Black Mountain #16, 1948. Private Collection. 191 Figure 2. Elaine de Kooning, Untitled, #15, 1948. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 192 Figure 3. Willem de Kooning, Judgment Day, 1946. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 193 Figure 4. Elaine de Kooning, Detail, Untitled #15, 1948. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 194 Figure 5. Hans Hofmann, Ecstasy, 1947. University of California, Berkeley Art Museum. 195 Figure 6. Elaine de Kooning, Untitled 11, 1948. Salander O’Reilly Galleries, New York. 196 Figure 7. Elaine de Kooning, Self Portrait #3, 1946. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 197 Figure 8. Elaine de Kooning, Detail, Self Portrait #3, 1946. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 198 Figure 9. Elaine de Kooning, Detail, Self Portrait #3, 1946. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 199 Figure 10. Elaine de Kooning, Untitled 12, 1948. Salander O’Reilly Galleries, New York. 200 Figure 11. Elaine de Kooning, Black Mountain #6, 1948. Salander O’Reilly Galleries, New York. 201 Figure 12. Grace Hartigan, Frank O’Hara, 1966. National Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 202 Figure 13. Elaine de Kooning, Kaldis #12, 1978. Private Collection. 203 Figure 14. Elaine de Kooning, Frank O’Hara, 1956. Private Collection. 204 Figure 15. Arshile Gorky, The Artist and His Mother, 1926-36. Whitney Museum of Art, New York. 205 Figure 16. Elaine de Kooning, Al Lazar #2, 1954. Private Collection. 206 Figure 17. Elaine de Kooning, Conrad #2, 1950. Private Collection. 207 Figure 18. Elaine de Kooning, JFK, 1963. -

SHFAP and Martha Henry Present

shfap SHFAP and Martha Henry present Pairings: Gandy Brodie / Bob Thompson: The Ecstasy of Influence, an exhibition about the painterly relationship of Gandy Brodie and Bob Thompson in the late 1950’s. Gandy Brodie and Bob Thompson both spent the summer of 1958 in Provincetown, Massachusetts, amidst a community of other artists that included Mimi Gross, Red Grooms, Jay Milder, Wolf Kahn, Emilio Cruz, Lester Johnson, Anne Tabachnick, Dody Müller and Christopher Lane. Art historian Judith Wilson characterized that Provincetown summer as exemplifying an “ecstasy of influence”: the influences of contemporary figurative painters on Thompson’s work. She wrote about this community in the 1998 Whitney Museum exhibition catalogue for Thompson’s retrospective. Jan Müller who died in January of 1958, was undeniably a significant influence on the developing Bob Thompson, despite the fact that they never met. However, the influences of other members of this community on Thompson have been less explored. Wilson touches on this as she quotes a mutual friend of Brodie and Thompson, the painter Emilio Cruz. Cruz has stated that Thompson painted “his first figurative paintings” in response to the influence of Gandy Brodie. In her Whitney essay, Wilson notes that “The gray-brown palette, division of the canvas into large rectangles of contrasting light and dark tones, and the mask- like treatment of faces, as in Brodie’s “The Penetration of a Thought”, 1958 and Thompson’s “Differences”, 1958, seems to bear this out.” This exhibition includes both “The Penetration of a Thought”, 1958 by Brodie and Thompson’s “Differences”, 1958, among 12 paintings all from the period steven harvey fine art projects gallery 24 east 73 street, #2f new york ny 10021 917.861.7312 office 780 riverside drive # 5aa new york ny 10032 212.281.2281 e [email protected] w www.shfap.com shfap between 1958 and 1964, exploring this influence and relationship between these two important post-war figurative painters. -

Oral History Interview with Leo Castelli

Oral history interview with Leo Castelli Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Leo Castelli AAA.castel69may Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Leo Castelli Identifier: AAA.castel69may Date: 1969 May 14-1973 June 8 Creator: Castelli, Leo (Interviewee) Cummings, Paul (Interviewer) Extent: 194 Pages (Transcript) Language: English -

Painterly Representation in New York: 1945-1975

PAINTERLY REPRESENTATION IN NEW YORK, 1945-1975 by JENNIFER SACHS SAMET A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2010 © 2010 JENNIFER SACHS SAMET All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Dr. Patricia Mainardi Chair of the Examining Committee Date Dr. Patricia Mainardi Acting Executive Officer Dr. Katherine Manthorne Dr. Rose-Carol Washton Long Ms. Martica Sawin Supervision Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract PAINTERLY REPRESENTATION IN NEW YORK, 1945-1975 by JENNIFER SACHS SAMET Advisor: Professor Patricia Mainardi Although the myth persists that figurative painting in New York did not exist after the age of Abstract Expressionism, many artists in fact worked with a painterly, representational vocabulary during this period and throughout the 1960s and 1970s. This dissertation is the first survey of a group of painters working in this mode, all born around the 1920s and living in New York. Several, though not all, were students of Hans Hofmann; most knew one another; some were close friends or colleagues as art teachers. I highlight nine artists: Rosemarie Beck (1923-2003), Leland Bell (1922-1991), Nell Blaine (1922-1996), Robert De Niro (1922-1993), Paul Georges (1923-2002), Albert Kresch (b. 1922), Mercedes Matter (1913-2001), Louisa Matthiasdottir (1917-2000), and Paul Resika (b. 1928). This group of artists has been marginalized in standard art historical surveys and accounts of the period. -

A Finding Aid to the Ivan C. Karp Papers and OK Harris Works of Art Gallery Records, 1960-2014, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Ivan C. Karp Papers and OK Harris Works of Art Gallery Records, 1960-2014, in the Archives of American Art Catherine S. Gaines and Joy Goodwin 2014 October 17 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Historical note.................................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1960-2013.................................................................... 5 Series 2: Administrative Files, 1969-2014................................................................ 9 Series 3: Exhibition Files, 1969-2014................................................................... -

Selections from the Archives of American Art Oral History Collection

1958 –2008 Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution | Winterhouse Editions, 2008 Published with the support of the Dedalus Foundation, Inc. 6 Introduction 8 Abraham Walkowitz 14 Charles Burchfield 20 Isamu Noguchi 24 Stuart Davis 32 Burgoyne Diller 38 Dorothea Lange 44 A. Hyatt Mayor 50 Edith Gregor Halpert 56 Jacob Lawrence 62 Emmy Lou Packard 70 Lee Krasner 76 Robert Motherwell 82 Leo Castelli 88 Robert Rauschenberg 92 Al Held 96 Katharine Kuh 102 Tom Wesselmann 106 Agnes Martin 112 Sheila Hicks 120 Jay DeFeo 126 Robert C. Scull 134 Chuck Close 142 Ken Shores 146 Maya Lin 152 Guerrilla Girls Perhaps no experience is as profoundly visceral for the historian than the Mark Rothko Foundation, and the Pasadena Art Alliance. Today to read and listen to individuals recount the stories of their lives and this project remains remarkably vigorous, thanks to support from the careers in an interview. Although the written document can provide Terra Foundation for American Art, the Brown Foundation of Houston, extraordinary insight, the intimacy of the one-on-one interview offers the Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation, the Art Dealers Association of a candor and immediacy rarely encountered on the page. America, and in particular Nanette L. Laitman, who has recently funded nearly 150 interviews with American craft artists. Intro- I am deeply grateful to the many people who have worked so hard to make this publication a success. At the Archives, I wish to thank ductionIn 1958, with great prescience, the Archives of American Art our oral history program assistant Emily Hauck, interns Jessica Davis initiated an oral history program that quickly became a cornerstone of and Lindsey Kempton, and in particular our Curator of Manuscripts, our mission. -

Brick Walk & Harvey

BRICK WALK & HARVEY catalog of works for sale Summer 2 0 0 9 Front cover: Earl Kerkam Head (Self-Portrait with Head on verso) 1950 (detail) Oil on canvasboard 28 x 22 inches Peter Acheson Lennart Anderson Richard Baker Chuck Bowdish Katherine Bradford Gandy Brodie Pat de Groot John Heliker Peter Joyce Earl Kerkam Kurt Knobelsdorf Robert Kulicke Sangram Majumdar Ruth Miller Graham Nickson Seymour Remenick Paul Resika EM Saniga Stuart Shils BRICK WALK & HARVEY Catalog of Works for Sale summer 2009 All right. I may have lied to you and about you, and made a few pronouncements a bit too sweeping, perhaps, and possibly forgotten to tag the bases here or there, And damned your extravagance, and maligned your tastes, and libeled your relatives, and slandered a few of your friends, O.K., Nevertheless, come back. - Kenneth Fearing from Love 20 cents the First Quarter Mile All works are for sale, please inquire to: BW&H .......Contact Kevin Rita BW&H .......Contact Steven Harvey Steven Harvey Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects LLC 780 Riverside Drive, #5aa New York, NY 10032 212-281-2281 [email protected] www.shfap.com or Kevin Rita Brick Walk Fine Art 322 Park Road West Hartford, Ct 06119 860-233-1730 [email protected] www.artnet.com: Brick Walk Fine Art Welcome to the second Brick Walk & Harvey catalog of works for sale. Brick Walk & Harvey is a collaboration between Steven Harvey of steven harvey fine art projects in New York and Kevin Rita of Brick Walk Fine Art in West Hartford, Connecticut. Our mission is to bring works of interest to your attention.