PDF Transcript of Recorded Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

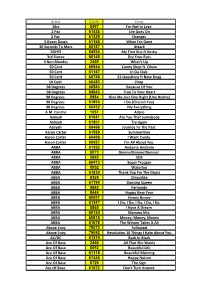

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Skain's Domain – Episode 5

Skain's Domain – Episode 5 Skain's Domain Episode 5 - April 20, 2020 0:00:01 Moderator: Wynton, you're ready? 0:00:02 Wynton Marsalis: I'm ready. 0:00:03 Moderator: Alright. 0:00:06 WM: I wanna thank all of you for joining me once again. This is Skain's Domain, we're talking about subjects significant and trivial, with the same intensity and feeling. We're gonna talk tonight... I'm gonna start off by talking about a series we're gonna start, which is, "How to develop your ability to hear, listen to music." I think that for many years, me and a great seer of the American vernacular, Phil Schaap, argued about the importance of music appreciation. We tend to spend a lot of time with musicians, talking about music, and we forget about the general audience of listeners, so I'm gonna go through 16 steps of hearing, over the time. I'm gonna be announcing when it is, and I'm just gonna talk about the levels of hearing from when you first start hearing music, to as you deepen your understanding of music, and you're able to understand more and more things, till I get to a very, very high level of hearing. Some of it comes from things that we all know from studying music and even what we like, what we listen to, but also it comes from the many different experiences I've had with great musicians, from the beginning. I can always remember hearing when I was a kid, the story of Ben Webster, the great balladeer on tenor saxophone. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

(Hymn by Men of MACC : Rise Up, O

(Hymn by Men of MACC : Rise Up, O Church of God.) (Scripture reading of Matthew 11:16-19, 25-30 by Jonathon Manker.) (Hymn: Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah.) >>FAY: Please be seated. Will you join with me in prayer, please? O God source of all light, love, and peace, holy are you. All our worship and praise is yours this day and may it be acceptable in your sight. Faithful God, as we as a general assembly of the Christian Church Disciples of Christ gather together this week in Indianapolis, may we seek unity and not uniformity above all things. May we have the courage to be a voice for the voiceless, to speak right to wrongs, to offer words of hope to one another and to continue to be a movement for wholeness in a fragmented world. Faithful God, help us to be courageous and to do and be who you are calling us to be. We pray this week will feed and water and fill the empty vessels who serve you and your church. We pray that both the clergy and the laypersons return to their congregations with new energy, that we can be the church that is needed in such a time as this, that we may be the good news from our doorsteps to the end of the earth. Great God of all people, as we gather this day for worship and prayer, we come lifting up to you the many, many people in our communities and around the world who are hurting. We continue to pray for the 65 million people displaced around the world due to war, famine and political unrest. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

08500238 SATB Double Choir a Cappella

P 137 Pastores Loquebantur (Anerio/ed. William B. Wells) • Peace On Earth (with “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear”) ______08500238 SATB Double Choir a cappella.....................$3.50 (Joyce Eilers) Patapan (arr. Lantz III) ______08743765 3-Part Mixed ...............................................$1.50 ______08738331 2-Part..........................................................$1.45 ______08743766 2-Part..........................................................$1.50 Patapan (arr. Ed Lojeski) ______08743769 TTB .............................................................$1.50 ______08406441 SATB ...........................................................$1.25 Peace, Evermore! (Jackson Berkey/Almeda Berkey) ______08406443 SSA.............................................................$1.40 ______08501135 SATB ...........................................................$1.35 Pater Noster (Javier Busto) Peace, Peace (arr. Fred Bock) ______08500175 SATB a cappella ..........................................$1.50 ______08738224 SATB ...........................................................$1.60 Pater Noster (Tchaikovsky/arr. Norman Luboff) ______08738350 3-Part..........................................................$1.40 ______08501030 SATB ...........................................................$1.25 ______08738148 2-Part..........................................................$1.40 Patterns in Performance (Sight Reading Resource Collection) ______08738477 Handbells ....................................................$1.50 (Joyce -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 08/11/2017 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 08/11/2017 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Shape of You - Ed Sheeran Someone Like You - Adele Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Piano Man - Billy Joel At Last - Etta James Don't Stop Believing - Journey Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Wannabe - Spice Girls Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Jackson - Johnny Cash Free Fallin' - Tom Petty Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Look What You Made Me Do - Taylor Swift I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Girl Crush - Little Big Town House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Body Like a Back Road - Sam Hunt Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Santeria - Sublime Summer Nights - Grease Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Turn The Page - Bob Seger Zombie - The Cranberries Crazy - Patsy Cline Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Kryptonite - 3 Doors Down My Girl - The Temptations Despacito (Remix) - Luis Fonsi Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Let It Go - Idina Menzel Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Monster Mash - Bobby Boris Pickett Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Love Shack - The B-52's My Way - Frank Sinatra In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Rolling In The Deep - Adele All Of Me - John Legend These -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Songs by Artist

TOTALLY TWISTED KARAOKE Songs by Artist 37 SONGS ADDED IN SEP 2021 Title Title (HED) PLANET EARTH 2 CHAINZ, DRAKE & QUAVO (DUET) BARTENDER BIGGER THAN YOU (EXPLICIT) 10 YEARS 2 CHAINZ, KENDRICK LAMAR, A$AP, ROCKY & BEAUTIFUL DRAKE THROUGH THE IRIS FUCKIN PROBLEMS (EXPLICIT) WASTELAND 2 EVISA 10,000 MANIACS OH LA LA LA BECAUSE THE NIGHT 2 LIVE CREW CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS ME SO HORNY LIKE THE WEATHER WE WANT SOME PUSSY MORE THAN THIS 2 PAC THESE ARE THE DAYS CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) TROUBLE ME CHANGES 10CC DEAR MAMA DREADLOCK HOLIDAY HOW DO U WANT IT I'M NOT IN LOVE I GET AROUND RUBBER BULLETS SO MANY TEARS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE UNTIL THE END OF TIME (RADIO VERSION) WALL STREET SHUFFLE 2 PAC & ELTON JOHN 112 GHETTO GOSPEL DANCE WITH ME (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & EMINEM PEACHES AND CREAM ONE DAY AT A TIME PEACHES AND CREAM (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS (DUET) 112 & LUDACRIS DO FOR LOVE HOT & WET 2 PAC, DR DRE & ROGER TROUTMAN (DUET) 12 GAUGE CALIFORNIA LOVE DUNKIE BUTT CALIFORNIA LOVE (REMIX) 12 STONES 2 PISTOLS & RAY J CRASH YOU KNOW ME FAR AWAY 2 UNLIMITED WAY I FEEL NO LIMITS WE ARE ONE 20 FINGERS 1910 FRUITGUM CO SHORT 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 21 SAVAGE, OFFSET, METRO BOOMIN & TRAVIS SIMON SAYS SCOTT (DUET) 1975, THE GHOSTFACE KILLERS (EXPLICIT) SOUND, THE 21ST CENTURY GIRLS TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 21ST CENTURY GIRLS 1999 MAN UNITED SQUAD 220 KID X BILLEN TED REMIX LIFT IT HIGH (ALL ABOUT BELIEF) WELLERMAN (SEA SHANTY) 2 24KGOLDN & IANN DIOR (DUET) WHERE MY GIRLS AT MOOD (EXPLICIT) 2 BROTHERS ON 4TH 2AM CLUB COME TAKE MY HAND -

Students - Links -… Page 2 of 5

Printed by: Gabe Gancarz March 23, 2018 2625638 PM Title: 03_B_02_Ramblings_2016 / Glenbard East - Students - Links -… Page 2 of 5 RAMBLINGS 2016 Glenbard East High School Lombard, Illinois Editor in Chief Kelly Womack Co-Editors Cynthia Cabral Ariel Barbee Tara Aggarwal Alyssa Palazzolo Readers Kelly Womack Cynthia Cabral Ariel Barbee Tara Aggarwal Alyssa Palazzolo Maggie Garrett Advisor Mr. Bill Littell Acknowledgements We would like to thank Ms. Wink and Mr. Cho who have provided all of the student artwork for Ramblings this year and years past. We would also Laura Sandoval - The City Printed by: Gabe Gancarz March 23, 2018 2625638 PM Title: 03_B_02_Ramblings_2016 / Glenbard East - Students - Links -… Page 3 of 5 like to thank Mr. Gancarz for helping us with Ramblings’ amazing layout and the many technical problems we stumbled across. And finally, a huge thank you to all the students who submitted work. This magazine just doesn’t happen without YOU! WRITINGS Taylor Harris - I Live In Tori Glaza - Parallels Tara Aggarwal - Villainous Woman Tori Glaza - Dear Mom... Cynthia Cabral - The Eyes of My Sammy Gonzalez - The Brush Lovely Foe Sammy Gonzalez - Questions Ariel Barbee - Valerie Taylor Harris - Character Sketch Alyssa Palazzolo - I Am From Taylor Harris - Skeptics Hymnal Gihan Abushanab - I Wear Taylor Harris - Untitled 1 Gihan Abushanab - Untitled Taylor Harris - Untitled 2 Gihan Abushanab - Where I’m From Jesse Johnson - Crown of Thorns Khadijah Alexander - Nerdy to Flirty Emily Kates - We Are Strangers Ahmed Ali - A Dark Encounter Amber Llorens - Gone Andrea Anton - The Voice Alexis Melvin - The Bonfire Sarah Austin - We're Robbing Alexis Melvin - The People I am Blockbuster on Tuesday From Sam Batjes - Universal Thought BombAlexis Melvin - Tough Love Alex Battaglia - Bird Song Carlos Meyers - I'm From.. -

Karaoke List

Artist Code Song 10cc 8497 I'm Not In Love 2 Pac 61426 Life Goes On 2 Pac 61425 Changes 3 Doors Down 61165 When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars 60147 Attack 3OH!3 84954 My First Kiss ft Kesha 3rd Storee 60145 Dry Your Eyes 4 Non Blondes 2459 What's Up 50 Cent 60944 Candy Shop ft. Olivia 50 Cent 61147 In Da Club 50 Cent 60748 21 Questions ft Nate Dogg 50 Cent 60483 Pimp 98 Degrees 60543 Because Of You 98 Degrees 84943 True To Your Heart 98 Degrees 8984 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 61890 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 60332 My Everything A.M. Canche 1051 Adoro Aaliyah 61681 Are You That Somebody Aaliyah 61801 Try Again Aaliyah 60468 Journey To The Past Aaron Carter 61588 Summertime Aaron Carter 60458 I Want Candy Aaron Carter 60557 I'm All About You ABBA 61352 Andante Andante ABBA 8073 Gimme!Gimme!Gimme! ABBA 2692 SOS ABBA 60413 Super Trooper ABBA 8952 Waterloo ABBA 61830 Thank You For The Music ABBA 8369 Chiquitita ABBA 61199 Dancing Queen ABBA 8842 Fernando ABBA 8444 Happy New Year ABBA 60001 Honey Honey ABBA 61347 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA 8865 I Have A Dream ABBA 60134 Mamma Mia ABBA 60818 Money, Money, Money ABBA 61678 The Winner Takes It All Above Envy 79073 Followed Above Envy 79092 Revolution 10 Things I Hate About You AC/DC 61319 Back In Black Ace Of Base 2466 All That She Wants Ace Of Base 8592 Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 61118 Beautiful Morning Ace Of Base 61346 Happy Nation Ace Of Base 8729 The Sign Ace Of Base 61672 Don't Turn Around Acid House Kings 61904 This Heart Is A Stone Acquiesce 60699 Oasis Adam -

Selena Star - Poems

Poetry Series Selena Star - poems - Publication Date: 2008 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Selena Star(August 5) I Dont Get On Really Anymore And I Have Had Writers Block For Years But You Can Find Me On MySpace... www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 # Missing What Was Once Mine # '08 Heartache is the worst pain It eats at your soul Sending flashbacks, memories Of what once was Like the tickle of your breath Brushing against my skin Oh, but i would get you back! With nothing but a butterfly kiss Or the way i would fall asleep in your arms Feeling so safe, so warm I could lay there for hours As long as you were beside me Ovcourse you're always on my mind Hour to hour each day I'll just be sitting here Letting my heart rip to shreads www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 (sorry i posted such an awful poem) Selena Star www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 3 # The Lease I Can Ask # '08 Our love, Oh it was great! Do you remember our first kiss? In your car after our first date. I know that NOW you must hate me, But babe...i still love you. And the least i can ask, Is for you to STILL love me too. www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 4 I know that NOW you're with her, And probly having a great time. While im here lonely and miserable, Wishing you were still mine.