Draft Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Institute of Commonwealth Studies

University of London INSTITUTE OF COMMONWEALTH STUDIES INTERVIEW WITH MATTHEW NEUHAUS SO: Sue Onslow (Interviewer) MN: Matthew Newhaus (Respondent) SO: This is Dr Sue Onslow talking to Mr Matthew Neuhaus, Australian Ambassador in Zimbabwe, at Senate House on 5th June, 2013. Matthew, thank you very much indeed for coming to talk to me. Please, I wondered if you could begin by saying, how did your interest and engagement with things Commonwealth begin? MN: My real engagement with the Commonwealth began in late ‘85/1986 when I did my MPhil in International Relations at Cambridge University. I chose as my topic the negotiation of Zimbabwe’s independence and particularly the Commonwealth role in that, especially through the Lusaka CHOGM and the subsequent Lancaster House negotiations where the Commonwealth’s role has often being rather undersold, but was actually quite important. And recently I had the privilege of a breakfast with Andrew Young, in which we recalled that engagement as well. But the other reason for doing the subject at the time, was that I was someone who had spent a lot of my childhood in Africa and had already had my first diplomatic posting in Kenya at the time. But the reason for picking on Zimbabwe was more because of the lessons that could be learnt from that, from the bigger issue of South Africa at the time. And indeed subsequently, when I returned to Canberra, I did write a paper on that, and I do believe that there has always been quite a nexus between developments in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe and South Africa. -

Aussie News Issue 2 June 2011 FINAL for Website

Aussie News ISSUE 2 JUNE 2011 A U S T R A L I A N H I G H C O M M I S S I O N A B U J A PAGE 2 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Aussie News High Commissioner’s 2 Message High Commissioner’s Message Australia Day Event & 3 Honours List It is a great pleasure to write the welcome message for our second edition of the Australian High Commission Abuja International Women’s 4 Newsletter. Day Lunch It has been a busy first six months of 2011 with the successful Presentation of 4 hosting of the Australia Day function at the Residence on Credentials: Niger 26 January, the staging of an Anzac Day dawn service in Abuja in April, a well attended International Women’s Day function Countries of Accredita- 5 at the Residence and the holding of an Australian Film Festival tion: Republic of Niger in honour of Reconciliation Week, featuring the Australian cinema musical comedy, Development Coopera- 6 Bran Nue Dae, at Silverbird Cinema in Abuja on 31 May. tion Programs There have been some very good outcomes in our efforts to engage with the West and Central African region more generally. I was honoured to present credentials in Mining Indaba 2011 7 Niamey in January as the first Australian Ambassador to be accredited to the Republic Australia visit of MFA 8 of Niger. I accompanied the Prime Minister’s Special Envoy to La Francophonie, Bill Permanent Secretary Fisher, on his successful visit to the Republics of Gabon, Cameroon and Congo in March. -

Official Series Document

OPCW Executive Council Ninety-Sixth Session EC-96/2 9 –12 March 2021 12 March 2021 Original: ENGLISH REPORT OF THE NINETY-SIXTH SESSION OF THE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL 1. AGENDA ITEM ONE – Opening of the session The Chairperson of the Executive Council (hereinafter “the Council”), Ambassador Agustín Vásquez Gómez of El Salvador, opened its Ninety-Sixth Session in The Hague at 10:19 on 9 March 2021. The Council observed a minute’s silence in memory of and out of respect for all those around the world who had lost their lives due to the COVID-19 pandemic. 2. AGENDA ITEM TWO – Adoption of the agenda 2.1 The Council considered and adopted the following agenda: 1. Opening of the session 2. Adoption of the agenda 3. Opening statement by the Director-General 4. Reports by the Vice-Chairpersons on the activities conducted under their respective clusters of issues 5. General debate 6. Status of implementation of the Convention: (a) Reports by the Director-General on destruction-related issues (b) Implementation of the Conference of the States Parties and Executive Council decisions on destruction-related issues (c) Elimination of the Syrian chemical weapons programme (d) Other verification-related issues (e) Destruction-related plans and facility agreements (f) Addressing the threat from chemical weapons use CS-2021-2847(E) distributed 19/03/2021 *CS-2021-2847.E* EC-96/2 page 2 (g) Technical Secretariat’s activities: update on the OPCW Fact-Finding Mission in Syria (h) Timely submission of declarations under Article VI of the Convention (i) Implementation by the Technical Secretariat in 2020 of the regime governing the handling of confidential information (j) Status of implementation of the Verification Information System 7. -

ICC-ASP/18/INF.1 Assembly of States Parties

Advance version International Criminal Court ICC-ASP/18/INF.1 Distr.: General Assembly of States Parties 31 December 2019 English, French and Spanish only Eighteenth session The Hague, 2-7 December 2019 Delegations to the eighteenth session of the Assembly of States Parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court The Hague, 2 to 7 December 2019 Délégations présentes à la dix-huitième session de l’Assemblée des États Parties au Statut de Rome de la Cour pénale internationale La Haye, du 2 au 7 décembre 2019 Delegaciones asistentes al decimoctavo período de sesiones de la Asamblea de los Estados Partes en el Estatuto de Roma de la Corte Penal Internacional La Haya, 2 al 7 de diciembre de 2019 I1-EFS-191231 ICC-ASP/18/INF.1 Advance version Content / Table des matières / Índice Page I. States Parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court / États Parties au Statut de Rome de la Cour pénale internationale / Estados Partes en el Estatuto de Roma de la Corte Penal Internacional ................... 3 II. Observer States / États observateurs / Estados observadores .............................................................................................. 32 III. States invited to be present during the work of the Assembly / Les États invités à se faire représenter aux travaux de l’Assemblée / Los Estados invitados a que asistieran a los trabajos de la Asamblea ..................... 35 IV. Entities, intergovernmental organizations and other entities / Entités, organisations intergouvernementales et autres entités / Entidades, Organizaciónes intergubernamentales y otras entidades ....................... 36 V. Non-governmental organizations / Organisations non gouvernementales / Organizaciónes no gubernamentales ....................................................................... 38 2 I1-EFS-191231 Advance version ICC-ASP/18/INF.1 I. -

October - November 2006

centre for democratic institutions CDI.News Newsletter of the Centre for Democratic Institutions October - November 2006 Dear Colleagues, In this issue Welcome to the October-November 2006 issue of CDI.News from the Centre for Democratic Institutions (CDI), Australia. Recent Activities This issue focusses on our recent Respon- 2006 CDI Responsible Parliamentary sible Parliamentary Course and a range of Government Course concludes ....................2 new activities CDI is undertaking. CDI International Political Party CDI was established in 1998 by the Minister for Foreign Assistance Roundtable .................................2 Affairs and Trade, the Hon Alexander Downer, to assist in the development and strengthening of democratic institu- CDI and Senior U.S. Officials Discuss tions in developing countries. CDI’s work combines techni- Democracy Promotion .................................3 cal assistance and capacity building programs, networking, CDI Deputy Director & and interpersonal and knowledge exchange, including the Program Manager Appointed .......................3 dissemination of CDI’s original research on democracy and Dialogue with International Visitors its institutions. Our focus countries comprise Indonesia and August-September '06 ..................................4 Timor-Leste in South East Asia and Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu in Melanesia. CDI appears before the JSCFADT Human Rights Sub-Committee .....................5 CDI’s central goal is to support these regional focus coun- tries in strengthening -

Official Series Document

OPCW Executive Council Ninety-Sixth Session EC-96/DG.19 9 – 12 March 2021 9 March 2021 Original: ENGLISH OPENING STATEMENT BY THE DIRECTOR-GENERAL TO THE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL AT ITS NINETY-SIXTH SESSION (FULL VERSION) 1. I warmly welcome all delegations to the Ninety-Sixth Session of the Executive Council. 2. At the outset, I would like to thank Ambassador Agustín Vásquez Gómez for his continuing able leadership and guidance of the Council. 3. We commence the first Council session of the year by recognising our achievements and preparing for the challenges that lie ahead. 4. At the end of 2020, the first part of the Twenty-Fifth Session of the Conference of the States Parties was held, in an adapted modality, from 30 November to 1 December. The successful organisation and delivery of this event was the result of the goodwill and understanding of States Parties, and of the diligent preparatory efforts of the Secretariat staff. 5. The Secretariat remains committed to ensuring that the session is held in accordance with the statutory requirements of the Convention and with the highest possible standards of health and safety for all delegates and Secretariat staff members. 6. In this context, the Secretariat continues to explore options and modalities for conducting hybrid or fully online meetings of the OPCW policy-making organs. Identification of the requirements for an OPCW remote platform is currently under way. Technical preparations will begin, including the procurement of hardware and software components, installation and integration with existing conference systems, and testing. 7. Once in place, an introductory session on the use of the platform will be offered to State Party delegates in the summer. -

Institute of Commonwealth Studies

University of London INSTITUTE OF COMMONWEALTH STUDIES VOICE FILE NAME: The Hon. John Howard Key: SO: Sue Onslow (Interviewer) JH: Hon. John Howard (Respondent) SO: Sue Onslow talking to Mr John Howard in Sydney on 31st March, 2014. Sir, thank you very much indeed for agreeing to talk to us for this project. I wonder if you could begin, please Sir, by reflecting when you were at the Treasury in the late 1970s and early 1980s while Malcolm Fraser was, of course, an extremely active Commonwealth head as Prime Minister of Australia. Was there a particular Commonwealth dimension to any of your work, or was it focused exclusively on Australian affairs and domestic policy? JH: There wasn’t a particular Commonwealth focus, not even in the context of Australia’s international economic relations. We were a participant in certain Commonwealth programmes and I went to a number of meetings of the Commonwealth Finance ministers. I recall going to several of them, not all of them. I think I went to one in Malta, I went to one in London and I went to one in the Bahamas. I also went to one in Canada in Toronto in probably 1982. But there wasn’t a great Commonwealth emphasis, no. No, there wasn't. SO: It’s been commented those Commonwealth Finance Ministers’ meetings are enormously valuable for smaller states, and I wondered if Australia, as a large power within the Commonwealth, had the same attitude that they were beneficial? JH: Well, I’m trying to recall and when you recall these things, you obviously remember what had the biggest impact on you. -

Corrigé Corrected

Corrigé Corrected CR 2018/22 International Court Cour internationale of Justice de Justice THE HAGUE LA HAYE YEAR 2018 Public sitting held on Tuesday 4 September 2018, at 10 a.m., at the Peace Palace, President Yusuf presiding, on the Legal Consequences of the Separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965 (Request for advisory opinion submitted by the General Assembly of the United Nations) ____________________ VERBATIM RECORD ____________________ ANNÉE 2018 Audience publique tenue le mardi 4 septembre 2018, à 10 heures, au Palais de la Paix, sous la présidence de M. Yusuf, président, sur les Effets juridiques de la séparation de l’archipel des Chagos de Maurice en 1965 (Demande d’avis consultatif soumise par l’Assemblée générale des Nations Unies) ________________ COMPTE RENDU ________________ - 2 - Present: President Yusuf Vice-President Xue Judges Tomka Abraham Bennouna Cançado Trindade Donoghue Gaja Sebutinde Bhandari Robinson Gevorgian Salam Iwasawa Registrar Couvreur - 3 - Présents : M. Yusuf, président Mme Xue, vice-présidente MM. Tomka Abraham Bennouna Cançado Trindade Mme Donoghue M. Gaja Mme Sebutinde MM. Bhandari Robinson Gevorgian Salam Iwasawa, juges M. Couvreur, greffier - 4 - The Republic of South Africa is represented by: H.E. Mr. V. B. Koloane, Ambassador of the Republic of South Africa to the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Ms J. G. S. de Wet, Chief State Law Adviser (International Law), Department of International Relations and Co-operation, Ms T. Steenkamp, State Law Adviser (International Law), Department of International Relations and Co-operation, Mr. P. A. Stemmet, Legal Counsellor, Embassy of the Republic of South Africa in the Kingdom of the Netherlands. -

From Howard to Abbott: Explaining Change in Australia's Foreign Policy Engagement with Africa

From Howard to Abbott: Explaining change in Australia’s foreign policy engagement with Africa Nikola Pijovic MA (Global Studies), University of Wroclaw/Roskilde University BA (Hons) Classics, University of Adelaide A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University. 21 February 2017 © Copyright by Nikola Pijovic 2017 Statement of originality This thesis represents my original work unless otherwise acknowledged. Research from this thesis has also been published in the following journal articles: Nikola Pijovic, “The Commonwealth: Australia’s Traditional ‘Window’ into Africa”, The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs 103:4, August 2014, 383-398. David Mickler and Nikola Pijovic, “Engaging an Elephant in the Room? Locating Africa in Australian Foreign Policy”, Australian Journal of Politics & History 61:1, March 2015, 100-120. Nikola Pijovic, “The Liberal National Coalition, Australian Labor Party and Africa: two decades of partisanship in Australia’s foreign policy”, Australian Journal of International Affairs 70:5, October 2016, 541-562. Nikola Pijovic, 21 February 2017 Acknowledgements In the process of researching and writing this thesis I have become indebted to a whole lot of people, either for their insights and guidance, remarks and criticism, patience, or simple company. I would like to acknowledge and thank my supervisors. I thank Professors John Ravenhill, Roger Bradbury, Michael L’Estrange, and Dr Tanya Lyons for their guidance, support and insights which -

Official-Series Document

THE COU OPCW Executive Council Ninety-Third Session EC-93/2 10 – 12 March 2020 12 March 2020 Original: ENGLISH REPORT OF THE NINETY-THIRD SESSION OF THE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL 1. AGENDA ITEM ONE – Opening of the session The Chairperson of the Executive Council (hereinafter “the Council”), Ambassador Andrea Perugini of Italy, opened its Ninety-Third Session in The Hague at 10:03 on 10 March 2020. 2. AGENDA ITEM TWO – Adoption of the agenda The Council considered and adopted the following agenda: 1. Opening of the session 2. Adoption of the agenda 3. Opening statement by the Director-General 4. Reports by the Vice-Chairpersons on the activities conducted under their respective clusters of issues 5. General debate 6. Status of implementation of the Convention: (a) Reports by the Director-General on destruction-related issues (b) Implementation of the Conference of the States Parties and Executive Council decisions on destruction-related issues (c) Elimination of the Syrian chemical weapons programme (d) Other verification-related issues (e) Addressing the threat from chemical weapons use (f) Technical Secretariat’s activities: update on the OPCW Fact-Finding Mission in Syria (g) Timely submission of declarations under Article VI of the Convention (h) Implementation by the Technical Secretariat in 2019 of the regime governing the handling of confidential information (i) Status of implementation of the Verification Information System CS-2020-2345(E) distributed 12/03/2020 *CS-2020-2345.E* EC-93/2 page 2 7. Countering chemical terrorism 8. Administrative and financial matters: (a) Rules of Procedure of the Advisory Body on Administrative and Financial Matters (b) Report of the Advisory Body on Administrative and Financial Matters (c) Nominations for membership of the Advisory Body on Administrative and Financial Matters (d) Status of implementation of the External Auditor’s recommendations (e) Report on the status of implementation of the enterprise resource planning system (f) New External Auditor of the OPCW (g) Adjustment to the Director-General’s gross salary 9. -

Preparatory Committee for the 1995 Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons

Preparatory Committee for the 1995 Conference NPT/CONF.1995/PC.II/3 21 January 1994 of the Parties to the Treaty ORIGINAL: ENGLISH on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons PROGRESS REPORT OF THE PREPARATORY COMMITTEE FOR THE 1995 CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES TO THE TREATY ON THE NON-PROLIFERATION OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS (Second session) INTRODUCTION 1. Pursuant to the decision of the Preparatory Committee at its first session, held at United Nations Headquarters in New York from 10 to 14 May 1993, the Preparatory Committee for the 1995 Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons held its second session at United Nations Headquarters in New York from 17 to 21 January 1994. 2. The following 118 States Parties participated in the work of the Preparatory Committee at its second session: Afghanistan, Albania, Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belgium, Benin, Botswana, Brunei Darussalam, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, Canada, Cape Verde, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Denmark, Ecuador, Egypt, Estonia, Ethiopia, Fiji, Finland, France, Gabon, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala, Holy See, Hungary, Iceland, Indonesia, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Iraq, Ireland, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Latvia, Lebanon, Lesotho, Liberia, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Mali, Malta, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico, Mongolia, Morocco, -

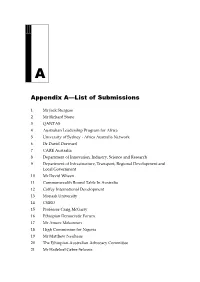

Appendix A: List of Submissions

A Appendix A—List of Submissions 1 Mr Jack Sturgess 2 Mr Richard Stone 3 QANTAS 4 Australian Leadership Program for Africa 5 University of Sydney - Africa Australia Network 6 Dr David Dorward 7 CARE Australia 8 Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research 9 Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Local Government 10 Mr David Wheen 11 Commonwealth Round Table In Australia 12 Coffey International Development 13 Monash University 14 CSIRO 15 Professor Craig McGarty 16 Ethiopian Democratic Forum 17 Mr Amare Mekonnen 18 High Commission for Nigeria 19 Mr Matthew Neuhaus 20 The Ethiopian-Australian Advocacy Committee 21 Mr Haileluel Gebre-Selassie 222 22 Dr David Lucas 23 South African High Commission 24 Universities Australia 25 Kenya High Commission 26 Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry 27 Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research 28 Dr Elizabeth Dimock 29 Dr Tanya Lyons 30 Department of Defence 31 World Vision Australia 32 Mr Peter Wakholi 33 Responsible Investment Consulting Pty Ltd 34 Dr Apollo Nsubuga-Kyobe 35 Associate Professor Geoffrey Hawker 36 The Hon Martin Ferguson, Minister for Resources and Energy, and Minister for Tourism 37 Australian Council for International Development 38 Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations 39 OxFam Australia 40 Australian Conservation Foundation 41 Professor Cherry Gertzel, AM 42 Department of Immigration and Citizenship 43 Australia Africa Business Council, ACT Chapter 44 Mr 'Dele Ogunmola 45 Professor Helen Ware