Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) Status Report 31 October 2017 Surveillance Data As of 16 October 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OFFICE of CHIEF ENGINEER (CENTRE) COMMUNICATION & WORKS DEPARTMENT KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PESHAWAR 1-Police Road Peshawar

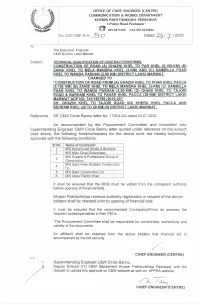

OFFICE OF CHIEF ENGINEER (CENTRE) COMMUNICATION & WORKS DEPARTMENT KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PESHAWAR 1-Police Road Peshawar 091-9211225 FAX 091-9210852 No. CEC/GSP /8-6/ f Dated: t4 / I2020 The Executive Engineer, C&W Division Lakki Marwat. Subject: TECHNICAL QUALIFICATION OF CONTRACTORS/FIRMS. CONSTRUCTION OF ROAD (A) GHAZNI KHEL TO PAR KHEL (5.156-KM) (B) ZANGI KHEL TO MELA MANDRA KHEL (3-KM) AND (C) GAMBILLA PHAR KHEL TO WANDA PASHAN (2.50 KM) DISTRICT LAKKI MARWAT. CHANGED TO "CONSTRUCTION OF ROAD FROM (A) GHAZNI KHEL TO PHAR KHEL PACCA (5.156 KM) (B) ZANGI KHEL TO MELA MANDRA KHEL (3-KM) (C) GAMBILLA PHAR KHEL TO WANDA PASHAN (2.50-KM) (D) GHANI KHEL TO TAJORI ROAD & BARHAM KHEL TO PAHAR KHEL PACCA (29-KM) DISTRICT LAKKI MARWAT ADP NO. 741/150795 (2019-20)" SH: GHAZNI KHEL TO TAJORI ROAD VIA KHERU KHEL PACCA AND BEHRAM KHEL (20 TO 29 KM) IN DISTRICT LAKKI MARWAT. Reference: SE C&W Circle Bannu letter No. 1729/4-GA dated 20-07-2020. As recommended by the Procurement Committee and forwarded vide Superintending Engineer C&W Circle Bannu letter quoted under reference on the subject cited above, the following firms/contractors for the above work are hereby technically approved with the following conditions: SI No. Name of Contractor 1. M/S Muhammad Shafiq & Brothers 2. M/S Mian Ghazi Enterprises M/S Experts & Professional Group of 3. Construction M/S Sabir Khan Bhattani Construction 4. Co. 5. M/S Sabir Construction Co. 6. M/S Abdur Rahim Khan It shall be ensured that the BOQ must be vetted from the competent authority before opening of Financial Bids. -

District. Project Description BE 2016-17 LAKKI MARWAT

District. Project Description BE 2016-17 LAKKI MARWAT LK15D00001-HT/LT Extension and distribution Transfo 6,100,000 LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00001-Training and Distribution of Sewing Machine amongst needy/ Poor 300,000 women i LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00002-Training and Distribution of Sewing Machine amongst needy/ Poor 2,142,067 women LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00003-Equipment for PWDs (hearing aid, white cane, Wheel Chair/ Tri-Cycle) 4,000,000 LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00004-Social uplift and livelihood program for females through Sewing 5,346,933 machine, LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00005-Operationalization of Bacha Khan Women Vocational Center Sarai 1,000,000 Naurang LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00006-Construction of Flood Protection wall at Different Locations in District 1,600,000 LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00007-Construction of Barani Water Tanks at Different Locations in District 300,000 LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00008-Repair & Rehabilitation of Rod Kohi Structure in District 700,000 LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00009-Construction and Lining of Water Courses in District Lakki Marwat 1,333,333 LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00010-Strengthening of Farmer's knowledge through training on safe use 5,566,936 ofpesticides LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00011-Provision of furniture for staff at BHUs 400,000 LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00012-Purchase of Medicine for Mobile Civil Dispensary VC Garzai 600,000 LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00014-Installation of P/Pump and laying of Pipe lines in UC Lakki City I,IIand 2,200,131 UC Takhti Khel, Landiwah, Pahar Khel Thal and Ghazni Khel LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00015-Functionalization of incomplete WSS 250,000 LAKKI MARWAT LK16D00016-Installation -

Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I

Form-V: List of Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I Serial No Name of contestng candidate in Address of contesting candidate Symbol Urdu Alphbeticl order Allotted 1 Sahibzada PO Ashrafia Colony, Mohala Afghan Cow Colony, Peshawar Akram Khan 2 H # 3/2, Mohala Raza Shah Shaheed Road, Lantern Bilour House, Peshawar Alhaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour 3 Shangar PO Bara, Tehsil Bara, Khyber Agency, Kite Presented at Moh. Gul Abad, Bazid Khel, PO Bashir Ahmad Afridi Badh Ber, Distt Peshawar 4 Shaheen Muslim Town, Peshawar Suitcase Pir Abdur Rehman 5 Karim Pura, H # 282-B/20, St 2, Sheikhabad 2, Chiragh Peshawar (Lamp) Jan Alam Khan Paracha 6 H # 1960, Mohala Usman Street Warsak Road, Book Peshawar Haji Shah Nawaz 7 Fazal Haq Baba Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H Ladder !"#$%&'() # 1413, Peshawar Hazrat Muhammad alias Babo Maavia 8 Outside Lahore Gate PO Karim Pura, Peshawar BUS *!+,.-/01!234 Khalid Tanveer Rohela Advocate 9 Inside Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H # 1371, Key 5 67'8 Peshawar Syed Muhammad Sibtain Taj Agha 10 H # 070, Mohala Afghan Colony, Peshawar Scale 9 Shabir Ahmad Khan 11 Chamkani, Gulbahar Colony 2, Peshawar Umbrella :;< Tariq Saeed 12 Rehman Housing Society, Warsak Road, Fist 8= Kababiyan, Peshawar Amir Syed Monday, April 22, 2013 6:00:18 PM Contesting candidates Page 1 of 176 13 Outside Lahori Gate, Gulbahar Road, H # 245, Tap >?@A= Mohala Sheikh Abad 1, Peshawar Aamir Shehzad Hashmi 14 2 Zaman Park Zaman, Lahore Bat B Imran Khan 15 Shadman Colony # 3, Panal House, PO Warsad Tiger CDE' Road, Peshawar Muhammad Afzal Khan Panyala 16 House # 70/B, Street 2,Gulbahar#1,PO Arrow FGH!I' Gulbahar, Peshawar Muhammad Zulfiqar Afghani 17 Inside Asiya Gate, Moh. -

Dera Ismail Khan Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (DERA ISMAIL KHAN DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH DERA ISMAIL KHAN DISTRICT 1,627,132 201,301 DARABAN TEHSIL 123,933 15,007 DARABAN QH 78,938 9591 DARABAN PC 26,932 3135 DARABAN 26,932 3135 058010101 4,721 405 058010102 694 71 058010103 1,777 181 058010104 1,893 210 058010105 2,682 360 058010106 1,161 141 058010107 1,113 135 058010108 471 151 058010109 1,352 163 058010110 1,857 225 058010111 3,636 425 058010112 2,619 281 058010113 2,956 387 GANDI ASHAK PC 6,942 873 DHAUL KA JADID 1,494 196 058010206 1,494 196 GANDI ASHAK 4,165 523 058010201 2,272 267 058010202 696 97 058010203 433 58 058010204 764 101 MOCHI WAL 1,283 154 058010205 1,283 154 GANDI UMAR KHAN PC 7,246 966 GANDI UMAR KHAN 6,972 930 058010401 1,579 229 058010402 1,710 237 058010403 1,792 226 058010404 1,891 238 KHIARA BASHARAT 105 18 058010405 105 18 KHIARA FATEH MOHAMMAD 169 18 058010406 169 18 GARA MAHMOOD PURDIL PC 6,414 771 GARA KHAN WALA 450 56 058010505 450 56 GARA MAHMOOD PURDIL 1,940 230 058010502 1,940 230 KOT ISA KHAN 2,806 341 058010503 1,270 157 Page 1 of 36 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (DERA ISMAIL KHAN DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 058010504 1,536 184 MASTAN 1,218 144 058010501 1,218 144 KIKRI PC 6,058 729 GANDI ISAB 952 118 058010606 952 118 GARA MIR ALAM 996 117 058010604 996 117 GARA MURID SHAH 363 57 058010605 363 57 KIKRI 2,833 330 058010601 1,241 150 058010602 1,592 180 KOT SHAH NAWAZ 914 107 058010603 914 -

Biodiversity of Sedges in Dera Ismail Khan District, Nwfp Pakistan

Sarhad J. Agric. Vol.24, No.2, 2008 BIODIVERSITY OF SEDGES IN DERA ISMAIL KHAN DISTRICT, NWFP PAKISTAN Sarfaraz Khan Marwat* and Mir Ajab Khan** ABSTRAC The present account of Cyperaceae is based on the results of the Taxonomical research work conducted in Dera Ismail Khan (D.I.Khan) district, North West Frontier Province (NWFP), Pakistan, during May 2005 - April 2006. 20 plant species of the family, belonging to 9 genera, were collected, preserved and identified. Plant specimens were mounted and deposited as voucher specimens in the Department of Botany, Quaid-I-University, Islamabad. Complete macro & microscopic detailed morphological features of these species were investigated. Key to the species of the area was developed for easy and correct identification & differentiation. The genera with number of species are: Bolboschoenus ( 1sp.), Cyperus ( 6 sp.), Eleocharis ( 2 sp.), Eriophorum (I sp.), Fimbristylis ( 5 sp.), Juncellus (1sp.), Pycreus ( I sp.), Schoenoplectus ( 2 sp.) and Scirpus (1sp). Key words: Taxonomy, Sedges and Dera Ismail Khan, Pakistan. INTRODUCTION Dera Ismail Khan (D.I.Khan) is the southern most in this family are the underground parts, shape of the district of N.W.F.P. lying between 31°.15’ and aerial stem, presence and arrangement of the leaves, 32°.32’North latitude and 70°.11’ and 71°.20’ East type of inflorescence, number and length of longitude with an elevation of 571ft. from the sea involucral bracts, shape and size of the spikelets, level. It has a total geographical land of 0.896 million arrangement of glumes, persistence of the rachilla, hectares and out of which 0.300 m.ha. -

Floristic Account of Submersed Aquatic Angiosperms of Dera Ismail Khan District, Northwestern Pakistan

Penfound WT. 1940. The biology of Dianthera americana L. Am. Midl. Nat. Touchette BW, Frank A. 2009. Xylem potential- and water content-break- 24:242-247. points in two wetland forbs: indicators of drought resistance in emergent Qui D, Wu Z, Liu B, Deng J, Fu G, He F. 2001. The restoration of aquatic mac- hydrophytes. Aquat. Biol. 6:67-75. rophytes for improving water quality in a hypertrophic shallow lake in Touchette BW, Iannacone LR, Turner G, Frank A. 2007. Drought tolerance Hubei Province, China. Ecol. Eng. 18:147-156. versus drought avoidance: A comparison of plant-water relations in her- Schaff SD, Pezeshki SR, Shields FD. 2003. Effects of soil conditions on sur- baceous wetland plants subjected to water withdrawal and repletion. Wet- vival and growth of black willow cuttings. Environ. Manage. 31:748-763. lands. 27:656-667. Strakosh TR, Eitzmann JL, Gido KB, Guy CS. 2005. The response of water wil- low Justicia americana to different water inundation and desiccation regimes. N. Am. J. Fish. Manage. 25:1476-1485. J. Aquat. Plant Manage. 49: 125-128 Floristic account of submersed aquatic angiosperms of Dera Ismail Khan District, northwestern Pakistan SARFARAZ KHAN MARWAT, MIR AJAB KHAN, MUSHTAQ AHMAD AND MUHAMMAD ZAFAR* INTRODUCTION and root (Lancar and Krake 2002). The aquatic plants are of various types, some emergent and rooted on the bottom and Pakistan is a developing country of South Asia covering an others submerged. Still others are free-floating, and some area of 87.98 million ha (217 million ac), located 23-37°N 61- are rooted on the bank of the impoundments, adopting 76°E, with diverse geological and climatic environments. -

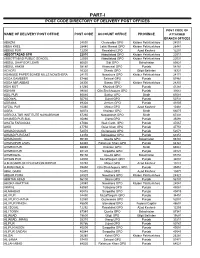

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

Map of District Bannu

Talaum ! Latamber Arangai ! ! Gumbatai ! Dragi Nar Shareef Wala ! ! FR BANNU Lwargai ! Sawye Mela ! Khorgi ! Khalboi ! Jangdad Shadi Khel ! ! Khalwai Kili ! Alamdar Ziandai Sind ! ! Miri Khel Siti ! Gul Akhtar ! ! Saiyid Khel KARAK Warana Mashan Khail Ali Khel ! ! ! Dwa Manzai Miri Khel Kurram Garhi ! ! ! Fazal Shah Garhi Bangi Khel Kozi Khel ! ! ! Manduri ! Pak Ismail Khel Musa Khel Domail Ghari Pal Mast Amir Kili ! ! ! ! ! Ghulam Kili Tonka Bizan Khel Walibat Kili !! Nasruddin !Bizan Khel ! Landi Bazar Degan ! ! ! Nasrat ! ! Mandezai Sharaf Mala Khel ! ! Banda Zar Khan Gala Khel Badshah Aqueduct Dara Shah ! ! ! Mirza Beg ! Sikandar Khel ! Kachozai ! Mara ! ! Kotkai Ibrahim Gul Sorang ! Karam Kili ! Shari Kili Hajigulan ! ! ! Kot Barra Beza Khel Arziman ! ! Bagha Khel ! Koti Sadat ! Garhi Saiyidan ! ! Babu Kili !Nazm Dirman Khel Nazar Dad Din Khojai Kauda ! Bodin Khelan ! ! ! ! ! Nirak Shinkandai Kot Beli Nur Muhammad ! ! Sargul Kili ! Koi Sadat Gulzar Mir Afzai ! Nadamin ! Bizan Khel ! ! ! Kotkai Firoz ! ! Shaikhan ! Umarzai Gulop Khel ! Kotkai Niamat ! ! NORTH WAZIRISTAN Bannu Fatima Khel Sherzad Khan ! Mama Khel (!! ! ! ! Muhammad Khel Jabbar Kili Barat Khel Miryan Abdur Rahman ! ! Sirik Sanzar Khel ! ! Kundi Dawar Shan ! Chaki Azim Mir Khel! ! ! ! !! Sher Ahmad Kili Haji Naurang Raza Ali Kotkai Piran Haji Khel ! ! ! ! Dandai Kili ! ! Wazir Hassan Khel ! Nasar Ali Teli Abezar Drab Khan Bahram Shah ! Nikarab Samandar Khan ! Pankzai ! ! Mian Gul Khel Imam Shah ! ! Swer Tup Mitha Khan ! Painda Khel ! Sherai ! ! ! ! ! Dreghundai Qalanari -

FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT REPORT a Hi-Tech Knowledge Management Tool for Disaster Risk Assessment at UNION COUNCIL Level

2015 FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT REPORT A Hi-Tech Knowledge Management Tool for Disaster Risk Assessment at UNION COUNCIL Level A PROPOSAL IN VIEW OF LESSONS LEARNED ISBN (P) 978-969-638-093-1 ISBN (D) 978-969-638-094-8 205-C 2nd Floor, Evacuee Trust Complex, F-5/1, Islamabad 195-1st Floor, Deans Trade Center, Peshawar Cantt; Peshawar Landline: +92.51.282.0449, +92.91.525.3347 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.alhasan.com ALHASAN SYSTEMS PRIVATE LIMITED A Hi-Tech Knowledge Management, Business Psychology Modeling, and Publishing Company 205-C, 2nd Floor, Evacuee Trust Complex, Sector F-5/1, Islamabad, Pakistan 44000 195-1st Floor, Dean Trade Center, Peshawar Can ; Peshawar, Pakistan 25000 Landline: +92.51.282.0449, +92.91.525.3347 Fax: +92.51.835.9287 Email: [email protected] Website: www.alhasan.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/alhasan.com Twi er: @alhasansystems w3w address: *Alhasan COPYRIGHT © 2015 BY ALHASAN SYSTEMS All rights reserved. No part of this publica on may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmi ed, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior wri en permission of ALHASAN SYSTEMS. 58 p.; 8.5x11.5 = A3 Size Map ISBN (P) 978-969-638-093-1 ISBN (D) 978-969-638-094-8 CATALOGING REFERENCE: Disaster Risk Reduc on – Disaster Risk Management – Disaster Risk Assessment Hyogo Framework for Ac on 2005-2015 Building the Resilience of Na ons and Communi es to Disasters IDENTIFY, ACCESS, AND MONITOR DISASTER RISKS AND ENHANCE EARLY WARNING x Risk assessments -

Census of Pakistan 1951 Village List

< .. Census 51 -No. :lo -i~ (I ) • I \. .' '~ ,; ·I .. - ' , . CEf\JSUS OF PAl<ISTAN, 1951 I )llkLAGE LIST . .. ~ I . l N.-W.F .P.- Banitu Distdcl -, OFFICE OF THE PROVINCIAL SUPERINTENDENT OF CENSUS, ~. 4 NORTH-WEST FRONTIER PnOVINCE, ~ .~ • PESHAWAR. ' .'. : , . ... ! March 1952 Price :'' l/-f- PR1NTED DY THE MANAGE R, GoVERNME I'}~' OF PAKISTAi... Pm;ss, K ARACHI PUBLISH ED DY 'l'HE MANAGER OF PUBLICA'l'JONS, KflRACH1: 1953 ' . -· ;'.~ , - b -· •S... ~ -· ~- .1 - -A~ --- L ·, . .· \ I .~~. ~. --~.~...._~~................... .._., .A£iliirJl1•£ NCE s I c:::::::; DIHR.IC T H'fr . T£14SIL uy 1111oiA wlio . lf!,OVINGf. OA STA Tl -·-"l't.... 011riu'r ----. I• .' ~£J.ISIL ....... ~ . lfAILWAY$ '~ . ~OAD.J R(VEA~ ~ .. ·~ . , lia!'1q ,f~: ict P. 1" ~ ;· Pa)·~fand " . lieJaiveM epe~ \~~i~I BN umd:r·~' l:i:<l tMl"fr,ie~ . out in tli~Fii:st.~~~·1)8 or,~akist~n· duritig . l es the p@p~l:at1on .,0f th~ s~a ~ep areas and thus ~reserves rnformwfion which would . iu ~he sfa:tisi~~al tota:ls of_the ~e ~ ~s Report.. I~ is ·hQped that the preparatien of.- this a has~s :f011 h,e cozyt1mied collection i!>f Village· Siatisp.cs. · . • . • • ·1 ·1·1> • . 'I . --!. .. ~ • • . ~ . ~ !iii ViiU1agq lisHsrin ·three parts ; first, the s~Friary Table of the District showing the p0pulation and ber,ot:houses, 'in tli.ousand.s, and the area in~·- miles; second, the list of Villages in al~habetical oi;der ·µ e~cll R'.e:ve~U!.\~~Fde sh,0win~ revenue nu b~r~, population, number of houses and 10cal de~ails; , a·Tha~p>'hao~u1eall mclex of tiht;i villages.of each e s11. -

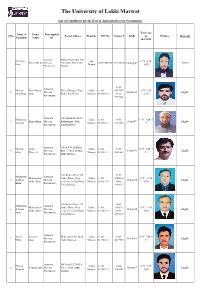

Final Lists of Eligible Candidates For

The University of Lakki Marwat List of Candidates for the Post of Assistant Director Procurment. Total Age Name of Father Post Applied S/No. Postal Address Domicile NIC No Contact # DOB on Pictures Remarks Candidate Name for 10-9-2018 Assistant Mohalla Sifat Khel, Vill Zia Ullah lakki 31 Y- 0 M- 1 Raham Dil Jan Director Abba Khel, Distt Lakki 112017643829-10313-8866327 11-Aug-87 Eligible khan Marwat 30 D Procurment Marwat 0345- Assistant Niamat Noor Nawaz Hostel Manager Kust Lakki 11201- 9857997 36 Y- 2 M- 2 Director 20-Jun-82 Eligible ullah khan khan Kohat B-2 Hostel Marwat 0338164-3 0333- 21 D Procurment 9977202 Assistant Vill, Sipahi khel P/O Muhamma Lakki 11201- 0346- 31 Y- 3 M- 5 3 Kamal khan Director Kotkashmir , Distt 5-Jun-87 Eligible d Ismail Marwat 9517589-1 9183789 D Procurment Lakki Marwat Assistant Vill & P/O Shahbaz Misbah Abdul Lakki 11201- 0345- 28 Y- 5 M- 7 4 Director khel , Tehsill & Distt 3-Apr-90 Eligible ullah Hameed Marwat 5428312-1 9891602 D Procurment lakki Marwat C/O Retired Prof , M. 0344- Muhamma Assistant Muhammad Akbar Home Near Lakki 11201- 9405826 32 Y- 11 M- 5 d Jibran Director 15-Sep-85 Eligible Akbar khan centenneil school Boys Marwat 2933824-7 0969- 26 D Khan Procurment Lakki Marwat 510353 C/O Retired Prof , M. 0969- Muhamma Assistant Muhammad Akbar Home Near Lakki 11201- 510353 32 Y- 11 M- 6 d Aman Director 15-Sep-85 Eligible Akbar khan centenneil school Boys Marwat 8118072-9 0343- 26 D khan Procurment Lakki Marwat 0375337 Assistant Sharif Sikandar Moh, Sifat khel ,Distt Lakki 11201- 0345- 38 Y- 7 M- -

Auditor General of Pakistan

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF TEHSIL MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATIONS IN DISTRICT DERA ISMAIL KHAN KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA AUDIT YEAR 2017-18 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ........................................................................................ i PREFACE ....................................................................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ iii I: Audit Work Statistics ........................................................................................... vi II: Audit observation classified by catagories….……………………………..….…vi III: Outcome Statistics ............................................................................................. vii IV: Irregularities pointed out ..................................................................................... vii V: Cost-Benefit Ratio……………………………...….……………………….…..vii CHAPTER 1 .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Tehsil Muniscipal Administration in District D I Khan ............................................... .. ...…1 1.1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Brief comments on Budget and Expenditure (Variance Analysis)........................ 1 1.1.3 Comments on the