Nuremberg and American Justice Matthew Lippman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Nuremberg” Tribunal, and Comparative Historicizing of War Criminals Tribunals Studies

European Studies Vol.20 (2020) 99-101 Panel Session Current judicial interpretations about “Tokyo” and “Nuremberg” Tribunal, and comparative historicizing of war criminals tribunals studies Kensuke Shiba My name is Kensuke Shiba. I’m honored by the preceding making for a total of 13 trials, as is tacitly understood from the introduction. I feel that today’s international symposium is of use of the plural form. However, the subsequent trials had in fact major significance. Having studied the Nuremberg trials as a been forgotten for some reason until recently. Today, from the historian, I have a few comments on the papers delivered today. perspectives of International Criminal Law or the international From a historical perspective as well, I felt that Judge Liu’s code of criminal procedure, experts are gathering to review the talk, in particular, was of extraordinary importance, as it was Tokyo and Nuremberg trials further; in the case of the latter, founded on modern legal practice. For some time we have been however, based on the above issues, I feel that the approach discussing the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials; considering how the thereto must emphasize the subsequent trials alongside the Nuremberg trials have been perceived in Germany, it seems that a International Military Tribunal and include the subsequent trials movement toward reconsidering the image of the trials as a whole when making a comparison with the Tokyo trials as well. In appeared in the late 1980s or just before the end of the Cold War. Germany, even laypeople seem to be developing an awareness of In fact, something that I emphasized in my own book (The a more complex image of the Nuremberg war criminal trials. -

Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context

Goettingen Journal of International Law 2 (2010) 3, 871-892 Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context Jessica Liang Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 872 A. Introduction .......................................................................................... 872 B. Superior Orders and the Soldier‘s Dilemma ........................................ 872 C. A Brief History of the Superior Orders Defense under International Law ............................................................................................. 874 D. Alternative Degrees of Attributing Criminal Responsibility: Finding the Right Solution to the Soldier‘s Dilemma ..................................... 878 I. Absolute Defense ................................................................................. 878 II. Absolute Liability................................................................................. 880 III.Conditional Liability ............................................................................ 881 1. Manifest Illegality ..................................................................... 881 2. A Reasonableness Standard ...................................................... 885 E. Frontiers of the Defense: Obedience to Civilian Orders? .................... 889 I. Operation under the Rome Statute ....................................................... 889 II. How far should the Defense of Superior Orders -

Nuremberg Academy Annual Report 2018

Annual Report International Nuremberg Principles Academy 1 Imprint The Annual Report 2018 has been Executive Board: published by the International Klaus Rackwitz (Director), Nuremberg Principles Academy. Dr. Viviane Dittrich (Deputy Director) It is available in English, German Edited by: and French and can be ordered Evelyn Müller at [email protected] Layout: or be downloaded on the website Martin Küchle Kommunikationsdesign www.nurembergacademy.org. Photos: Egidienplatz 23 International Nuremberg Principles Academy 90403 Nuremberg, Germany p. 9 Strathmore University, p. 20 Wayamo T + 49 (0) 911.231.10379 Foundation F + 49 (0) 911.231.14020 Printed by: [email protected] Druckwerk oHG Table of Contents 2 Foreword 5 The International Nuremberg Principles Academy 7 A Forum for Dialogue 8 • Events 14 • Network and Cooperation 19 Capacity Building 25 Research 29 Publications and Resources 32 Communications 34 Organization 37 Partners and Sponsors We proudly present the second edition of the Annual Report of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy. It reflects the activities and the achieve ments of the Nuremberg Academy throughout the year of 2018. It was another year of growth for the Nu Foreword remberg Academy with an increased num ber of events and activities at a peak level. Important anniversaries such as the 70th anniversary of the judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Rome Statute have been reflected in the Academy’s work and activities. Major international conferences – as far as we can see the largest of their kind, dedicated to these important dates worldwide – were held in Nuremberg in May and in October. -

Nuremberg Icj Timeline 1474-1868

NUREMBERG ICJ TIMELINE 1474-1868 1474 Trial of Peter von Hagenbach In connection with offenses committed while governing ter- ritory in the Upper Alsace region on behalf of the Duke of 1625 Hugo Grotius Publishes On the Law of Burgundy, Peter von Hagenbach is tried and sentenced to death War and Peace by an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges representing differ- ent local polities. The crimes charged, including murder, mass Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, one of the principal rape and the planned extermination of the citizens of Breisach, founders of international law with such works as Mare Liberum are characterized by the prosecution as “trampling under foot (On the Freedom of the Seas), publishes De Jure Belli ac Pacis the laws of God and man.” Considered history’s first interna- (On the Law of War and Peace). Considered his masterpiece, tional war crimes trial, it is noted for rejecting the defense of the book elucidates and secularizes the topic of just war, includ- superior orders and introducing an embryonic version of crimes ing analysis of belligerent status, adequate grounds for initiating against humanity. war and procedures to be followed in the inception, conduct, and conclusion of war. 1758 Emerich de Vattel Lays Foundation for Formulating Crime of Aggression In his seminal treatise The Law of Nations, Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel alludes to the great guilt of a sovereign who under- 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal takes an “unjust war” because he is “chargeable with all the Abolition of the Slave Trade evils, all the horrors of the war: all the effusion of blood, the The first international instrument to condemn slavery, the desolation of families, the rapine, the acts of violence, the rav- Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave ages, the conflagrations, are his works and his crimes . -

1. Outline the Scope of the 'Nuremberg Principles'. What Is

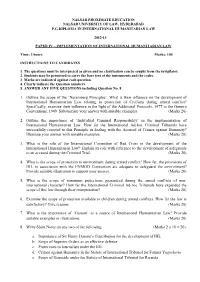

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2012-13 PAPER IV – IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Time: 3 hours Marks: 100 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions must be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator. 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. Marks are indicated against each question. 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers. 5. ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS including Question No. 8 1. Outline the scope of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’. What is their influence on the development of International Humanitarian Law relating to protection of Civilians during armed conflict? Specifically, examine their influence in the light of the Additional Protocols, 1977 to the Geneva Conventions, 1949. Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 2. Outline the importance of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ in the implementation of International Humanitarian Law. How far the International Ad-hoc Criminal Tribunals have successfully resorted to this Principle in dealing with the Accused of Crimes against Humanity? Illustrate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 3. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. (Marks 20) 4. What is the scope of protection to environment during armed conflict? How far, the provisions of IHL in association with the ENMOD Convention are adequate to safeguard the environment? Provide suitable illustration to support your answer. -

1. Examine the Impact of the 'Nuremberg Principles' on The

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2009-10 PAPER IV – Implementation of International Humanitarian Law Time: 2 hours and 30 minutes Marks: 75 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions to be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. All questions carry equal marks (15 marks each) 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS 1. Examine the impact of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’ on the development of IHL in the post Geneva Conventions phase. How far, the Nuremberg Principles have facilitated the implementation of the IHL? Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. 2. Examine the scope of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ as an important principle of International humanitarian law. How far this principle has been invoked at the International Plane for the effective implementation of IHL? Support your answer with suitable examples. 3. Write Short Notes on any three of the following a. Importance of Marten’s Clause b. Principle of Complimentarity c. Protections to witnesses during criminal trial d. Scope of War Crimes in the Statute of International Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia e. Scope of Crimes against in the Statute of International Tribunal for Rwanda 4. Examine the scope of ‘Rape’ as interpreted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda committed during the course of Non International Armed Conflict. Refer to leading case laws. 5. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. -

Amicus Brief of Nuremberg Scholars Omer Bartov Et

Supreme Court, U.S. No. 09-1262 2 0 2910 OFFICE OF: I HE ULERK upreme ourt of t e/l tnite btate PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH OF THE SUDAN, ET AL., Petitioners, V. TALISMAN ENERGY, INC., Respondent. On Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Second Circuit BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE NUREMBERG SCHOLARS OMER BARTOV, MICHAEL J. BAZYLER, DONALD BLOXHAM, CHRISTOPHER BROWNING, VIVIAN CURRAN, LAWRENCE DOUGLAS, HILARY EARL, HON. BRUCE J. EINHORN, RET., DAVID FRASER, STANLEY A. GOLDMAN, GREGORY S. GORDON, MICHAEL J. KELLY, MATTHEW ~LIPP ~MAN, MICHAEL MARRUS, FIONNUALA D. NI AOLAIN, BURT NEUBORNE, PIER PAOLO RIVELLO, AND CHRISTOPH J.M. SAFFERLING IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS JENNIFER GREEN MICHAEL BAZYLER Associate Professor Counsel of Record Director, Human Rights Professor of Law and Litigation and Inter- The "1939" Club Law national Advocacy Clinic Scholar in Holocaust and UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Human Rights Studies LAW SCHOOL CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY 225 19th Avenue South SCHOOL OF LAW Minneapolis, MN 55455 1 University Drive [email protected] Orange, CA 92866 612-625-7247 bazyler@chapman, edu 714-628-2500 Counsel for Amici Curiae May 20, 2010 COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. {800) 225-6964 OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831 Blank Page TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................. ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ......................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .............................. 3 ARGUMENT ........................................................ 4 I. CUSTOMARY INTERNATIONAL LAW AS FORMULATED AND APPLIED AT NUREMBERG PROVIDES A KNOWL- EDGE STANDARD FOR AIDING AND ABETTING LIABILITY ............................ 4 A. Nuremberg-Era British and French Military Courts Found that Knowl- edge Was the Proper Mens Rea for Aiding and Abetting Liability .............5 B. -

Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 46 | Issue 3 Article 4 5-2017 A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J. Sfekas Circuit Court for Baltimore City, Maryland Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons, International Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Sfekas, Stephen J. (2017) "A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 46 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol46/iss3/4 This Peer Reviewed Articles is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COURT PURE AND UNSULLIED: JUSTICE IN THE JUSTICE TRIAL AT NUREMBERG* Hon. Stephen J. Sfekas** Therefore, O Citizens, I bid ye bow In awe to this command, Let no man live Uncurbed by law nor curbed by tyranny . Thus I ordain it now, a [] court Pure and unsullied . .1 I. INTRODUCTION In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the common understanding was that the Nazi regime had been maintained by a combination of instruments of terror, such as the Gestapo, the SS, and concentration camps, combined with a sophisticated propaganda campaign.2 Modern historiography, however, has revealed the -

An American Tragedy

[Vol.119 NUREMBERG AND VIETNAM: AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY. By TELFORD TAYLOR. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, Inc., 1970. Pp. 224. $5.95. Joseph W. Bishop, Jr.- I have very little fault to find with Professor Taylor's exposition of the law, both our own constitutional law and the international law of war, applicable to the hostilities in Vietnam. It appears accurate, lucid, and reasonable-an extraordinarily good summary, for the lay as well as the legal reader, of some extraordinarily difficult legal problems. In particular, I am in complete agreement with his conclusion that the law of war, as difficult as it may be to apply and enforce, is very much better than no law at all. Its existence has averted a great deal of suffering in the wars which have afflicted our species during the last half century or so.' I have, of course, a few caveats about some of Professor Taylor's suggestions. For example, while agreeing that it might well be preferable to try the American soldiers accused of war crimes in the Song My incident before special military commissions composed of civilian lawyers and judges, instead of before courts-martial, I have some doubt whether that could legally be done. Certainly, if I were counsel for one of the accused, I could make a strong argument that under the Uniform Code of Military Justice 2 he is entitled to trial by general court-martial, with all the protection that implies. Likewise, I have greater doubt than Professor Taylor as to the validity of the so-called "Nuremberg defense," a concept which in essence would permit an individual lawfully to refuse to obey orders to participate in training for combat in Vietnam, to go to Vietnam, or even to report for induction, on the ground that compliance with such orders would put him in a position in which he would be compelled to commit violations of the law of war.3 My trouble with the concept is that I do not believe its basic premise. -

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society Series Editor: Stephen McVeigh, Associate Professor, Swansea University, UK Editorial Board: Paul Preston LSE, UK Joanna Bourke Birkbeck, University of London, UK Debra Kelly University of Westminster, UK Patricia Rae Queen’s University, Ontario, Canada James J. Weingartner Southern Illimois University, USA (Emeritus) Kurt Piehler Florida State University, USA Ian Scott University of Manchester, UK War, Culture and Society is a multi- and interdisciplinary series which encourages the parallel and complementary military, historical and sociocultural investigation of 20th- and 21st-century war and conflict. Published: The British Imperial Army in the Middle East, James Kitchen (2014) The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars, Gajendra Singh (2014) South Africa’s “Border War,” Gary Baines (2014) Forthcoming: Cultural Responses to Occupation in Japan, Adam Broinowski (2015) 9/11 and the American Western, Stephen McVeigh (2015) Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War, Gerben Zaagsma (2015) Military Law, the State, and Citizenship in the Modern Age, Gerard Oram (2015) The Japanese Comfort Women and Sexual Slavery During the China and Pacific Wars, Caroline Norma (2015) The Lost Cause of the Confederacy and American Civil War Memory, David J. Anderson (2015) Filming the End of the Holocaust Allied Documentaries, Nuremberg and the Liberation of the Concentration Camps John J. Michalczyk Bloomsbury Academic An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc LONDON • OXFORD • NEW YORK • NEW DELHI • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 Paperback edition fi rst published 2016 © John J. -

UNDERSTANDING POWER the INDISPENSABLE CHOMSKY Edited by Peter R

THE FOOTNOTES FOR: UNDERSTANDING POWER THE INDISPENSABLE CHOMSKY Edited by Peter R. Mitchell and John Schoeffel. Preface 1. For George Bush's statement, see "Bush's Remarks to the Nation on the Terrorist Attacks," New York Times, September 12, 2001, p. A4. For the quoted analysis from the New York Times's first "Week in Review" section following the September 11th attacks, see Serge Schmemann, "War Zone: What Would ‘Victory’ Mean?," New York Times, September 16, 2001, section 4, p. 1. Understanding Power: Preface Footnote Chapter One Weekend Teach-In: Opening Session 1. On Kennedy's fraudulent "missile gap" and major escalation of the arms race, see for example, Fred Kaplan, Wizards of Armageddon, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983, chs. 16, 19 and 20; Desmond Ball, Politics and Force Levels: The Strategic Missile Program of the Kennedy Administration, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980, ch. 2. On Reagan's fraudulent "window of vulnerability" and "military spending gap" and the massive military buildup during his first administration, see for example, Jeff McMahan, Reagan and the World: Imperial Policy in the New Cold War, New York: Monthly Review, 1985, chs. 2 and 3; Franklyn Holzman, "Politics and Guesswork: C.I.A. and D.I.A. estimates of Soviet Military Spending," International Security, Fall 1989, pp. 101-131; Franklyn Holzman, "The C.I.A.'s Military Spending Estimates: Deceit and Its Costs," Challenge, May/June 1992, pp. 28-39; Report of the President's Commission on Strategic Forces, Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, April 1983, especially pp. 7-8, 17, and Brent Scowcroft, "Final Report of the President's Commission on Strategic Forces," Atlantic Community Quarterly, Vol. -

Emotion and Memory of the Holocaust

Mark Goldstein 4.14.04 Professor Kansteiner Emotion and Memory of the Holocaust Surviving what was arguably the greatest act of genocide in human history, the Holocaust, entitles one the opportunity to recount one’s feeling and memories of the horror. In the aftermath of the Holocaust, an outpouring of eyewitness accounts by both survivors and perpetrators has surfaced as historical evidence. For many, this has determined what modern popular culture remembers about this atrocious event. Emotion obviously plays a vital role in the accounts of the survivors, yet can it be considered when discussing the historical significance of and the truth behind the murder of six million European Jews by the Third Reich? Emotion is the expression of thoughts and beliefs affected by feeling and sensibility of an individual regarding a certain event or individual. In terms of the Holocaust, emotion is overwhelmingly prevalent in the survivors’ tales of their experiences almost sixty years ago, conveyed in terms of life, death, and survival. As scholars often point out, the Holocaust evokes strong sentiments, and transmits and reinforces basic societal values. Through in- depth observation of various forms of media sources, this paper will argue that emotion and the lack thereof, as a repercussion of the Holocaust, through the testimonies of those who survived its trials and tribulations, has played an enormous role in determining historical knowledge of the genocide. In analyzing the stories which survivors of the concentration camps and their perpetrators have put forth as historical evidence supporting the findings of scholars, one must pose the question: where does fact end and emotional distortion of the subject begin? It is critical to approach this question with great care, so as to note that not all historical accounts of the Holocaust by survivors and perpetrators are laden with emotional input and a multilayered interpretation of the event.