The GAA to 1891. NLI Cs5a Gaato1891.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Guide 2020

The Ladies Gaelic Football Association Est 1974 Official Guide 2020 6th April The Ladies Gaelic Football Association The Ladies Gaelic Football Association was founded in Hayes Hotel, Thurles, County Tipperary on 18 July 1974. Four counties, Offaly, Kerry, Tipperary and Galway attended the meeting. However, eight counties namely Cork, Kerry, Tipperary, Waterford, Galway, Roscommon, Laois and Offaly participated in the first official All Ireland Senior Championship of that year, which was won by Tipperary. Today, Ladies Gaelic Football is played in all counties in Ireland. It is also played in Africa, Asia, Australia, Britain, Canada, Europe, New Zealand, South America and the USA on an organised basis. It is imperative for our Association to maintain and foster our supportive contact with our International units. Our Association in Ireland must influence and help Ladies Football Clubs Internationally and share the spirit of home with those who are separated physically from their homes and to introduce those who have no connection with Ireland to the enjoyment of our sporting culture and heritage. The structure of the Ladies Gaelic Football Association is similar to that of the GAA with Clubs, County Boards, Provincial Councils, Central Council and Annual Congress. The National President is elected for one term of four years and shall not serve two consecutive terms. The Association was recognised by the GAA in 1982. In the early years of its foundation, the Association used the rules in the Official Guide of the GAA in conjunction with its own rules. The Ladies Gaelic Football Association decided at a Central Council meeting on 7th October 1985 to publish its own Official Guide. -

GAA | Topic Notes

GAA | Topic Notes The situation with sport Before Industrial Revolution Informal, between parishes or towns, no rules, riots common Traditional games had a bad name and were in decline Industrial Revolution Difficult to play traditional games in cities, also less time Had to have something to do with free time though Factory owners and philanthropists began to set up clubs. Led to: Set rules Organised matches Modern games began in England, spread from there (the Empire) In Ireland, these new games such as football, rugby and cricket took over Problems with the Amateur Athletics Association in Ireland Only ‘gentlemen’ could compete – ruled out the working class No Sunday games – only time working class and farmers had to play Nationalists disliked English interference The start of the GAA 1 Michael Cusack and Maurice Davin joined together after Davin saw Cusack’s article in a newspaper saying that an Irish athletics body was needed Foundation of GAA Cusack published a notice with details of the foundation meeting 7 men showed up at Hayes Hotel on the 1st November 1884 Invited Parnell, Davitt, and Archbishop Croke of Cashel to be patrons Second meeting: Rules drawn up for Gaelic football and hurling, then printed on leaflets and distributed by Davin and Cusack Rough, flawed, imprecise Only one GAA club allowed in each parish Members of GAA forbidden to compete at meeting of rival athletics associations This rule abolished by Archbishop Croke later Rapid spread – 600 clubs after 2 years, matches reported in newspapers, inter-county matches -

Intouch March 2019

IssueNo185 March2019 ISSN1393-4813(Print) ISSN2009-6887(Online) School Tour Special Pay equality in the European Court Brexit concerns brought to Brussels Keeping InTouch 3 Interactive dialogue with members, and key news items 4 #NoMorePlasticPaddy Welcome to the March edition of InTouch Magazine and on enhancing social and communication skills of students our annual ‘School Tour Special’ featuring lots of terrific on the autistic spectrum. ideas for your forthcoming school tours. Brexit is on the front pages of all national newspapers Stories are incredibly powerful. With World Book Day most days at the moment. Our own members, some of on the horizon (7 March), we are proud to include a series whom cross the border to work each day have been in touch of age appropriate LGBT+ friendly books which introduce to raise their concerns on mutual recognition, pensions, diverse characters and family types. health insurance and so on. Our President, Joe Killeen and is St Patricks Day (17 March) INTO will be doing Northern Ireland Chair, Paddy McAllister, led a delegation something very special. Our Global Solidarity Campaign to Brussels last month to raise these concerns with key is asking all primary schools in Ireland to ditch single decision makers there. You can read more about the use plastics, a key component of the UN sustainable delegation in the magazine. development goals. Read more about our In just about six weeks’ time we will be gathering in #NoMorePlasticPaddy campaign inside. Galway for our Annual Congress. Delegates representing In a few days our Special Education Conference will take branches all over the country will be in attendance to decide place on 9 March. -

1988 Co Football Final

Co. Tipperary Senior Football Final Match Programme 1988 COIST E CHONTA E T HIOB RAD ARANN CRAOBH PE IL SI NN SEAR 1988 A N CHLUICH e: CHEAN NAIS NA -YRACYALAI v. flOOH ARO •• CILL tSIOLAIN , DDMHNACH 25t9IH8 .. J.15 (i.n.) • Rmeolf: Tomas 0 Lonargam CDISTE THIDBRAD ARANN THEAS IDMAINT SOISIR AN CHLUICHE LEATH CHEANNAIS (Ath·!mlft) v. Fanaithe na Maoille 1.45 (i.11.) Relteolf: Llalll 6 Sa/read ClAR ~IFI G I U ll . : SOp You outt e est In• us. Understanding the needs of our customers, and responding 10 them, is what cvcl)'body at Allied Irish Bank aimslO achieve. And through our sponsorship of the GM Al t [r e l~nd Schools Competitions \ve've learnt a few things, from the young tcams who have so much energy, commitment and determination. They strive to do the very best they can . And so do we at Allied Irish Bank. We aim to he the bl.:~t, not simply to satisfy our own ambitions, but for our C1I51Omers sake. II's your needs that bring out the best in li S. Allied Irish Banks Pic., 65/67 O'Connell St., Clonmel. Tel.: (052) 22500, 22865, 22 191 Allied Irish Banks Pic" 5/6 O'Connell St, Clonmel. Tel.: (052) 21097,21721,22666 Allied Irish Banks Pic., Main St., Carrick-on-Suir. Tel.: (05 1) 40026 / 7, 40890 Allied Irish Banks Pic .• 17 Main St., Fethard. Tel.: (052131408,31155 Allied Irish Banks PIc" Main SI .• Killenaule. Tel.: (052) 562 14 @ Allied Irish Bank You bring out the best in us. -

Annual Report

Introduction GAA Games Development 2014 Annual Report for the Irish Sports Council GAA Games Development 2014 A Annual Report for the Irish Sports Council @GAAlearning GAALearning www.learning.gaa.ie Foreword Foreword At a Forum held in Croke Park in June 2014 over 100 young people aged 15 – 19 were asked to define in one word what the GAA means to them. In their words the GAA is synonymous with ‘sport’, ‘parish’, ‘club’, ‘family’, ‘pride’ ‘passion’, ‘cultúr’, ‘changing’, ‘enjoyment’, ‘fun’, ‘cairdeas’. Above all these young people associated the GAA with the word ‘community’. At its most fundamental level GAA Games Development – through the synthesis of people, projects and policies – provides individuals across Ireland and internationally with the opportunity to connect with, participate in and contribute as part of a community. The nature and needs of this unique community is ever-changing and continuously evolving, however, year upon year GAA Games Development adapts accordingly to ensure the continued roll out of the Grassroots to National Programme and the implementation of projects to deliver games opportunities, skill development and learning initiatives. As recognised by Pierre Mairesse, Director General for Education and Culture in the European Commission, these serve to ‘go beyond the traditional divides between sports, youth work, citizenship and education’. i Annual Report for the Irish Sports Council. GAA Games Development 2014 2014 has been no exception to this and has witnessed some important milestones including: 89,000 participants at Cúl Camps, the introduction of revised Féile competitions that saw the number of players participating in these tournaments increase by 4,000, as well as the first ever National Go Games Week - an event that might have seemed unlikely less than a decade ago. -

Camogie Development Plan 2019

Camogie Development Plan 2019 - 2022 Vision ‘an engaged, vibrant and successful camogie section in Kilmacud Crokes – 2019 - 2022’ Camogie Development Ecosystem; 5 Development Themes Pursuit of Camogie Excellence Funding, Underpinning everything we do: Part of the Structure & ➢ Participation Community Resources ➢ Inclusiveness ➢ Involvement ➢ Fun ➢ Safety Schools as Active part of the Volunteers Wider Club • A player centric approach based on enjoyment, skill development and sense of belonging provided in a safe and friendly environment • All teams are competitive at their age groups and levels • Senior A team competitive in Senior 1 league and championship • All players reach their full potential as camogie players • Players and mentors enjoy the Kilmacud Crokes Camogie Experience • Develop strong links to the local schools and broader community • Increase player numbers so we have a minimum of 40 girls per squad OBJECTIVES • Prolong girls participation in camogie (playing, mentoring, refereeing) • Minimize drop-off rates • Mentors coaching qualifications are current and sufficient for the level/age group • Mentors are familiar with best practice in coaching • Well represented in Dublin County squads, from the Academy up to the Senior County team • More parents enjoying attending and supporting our camogie teams Milestones in Kilmacud Crokes Camogie The Camogie A dedicated section was nursery started U16 Division 1 Teams went from started in 1973 by County 12 a side to 15 a Promoted Eileen Hogan Champions Bunny Whelan side- camogie in -

Grid Export Data

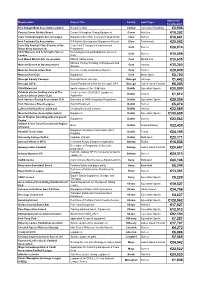

Amount to Organisation Project Title County Sport Type be allocated Irish Dragon Boat Association Limited Buoyancy Aids Carlow Canoeing / Kayaking €3,998 County Cavan Athletic Board Cavan / Monaghan Timing Equipment Cavan Athletics €19,302 Clare Schoolboy/girls Soccer League Equipment for CSSL newly purchased facility Clare Soccer €18,841 Irish Taekwon-Do Association ITA Athlete Development Equipment Project Clare Taekwondo €20,042 Cork City Football Club (Friends of the Cork City FC Equipment Improvement Cork Soccer Rebel Army Society Ltd) Programme €28,974 Cork Womens and Schoolgirls Soccer Increasing female participation in soccer in Cork Soccer League Cork €10,599 Irish Mixed Martial Arts Association IMMAF Safety Arena Cork Martial Arts €10,635 Munster Hockey Funding for Equipment and Munster Branch of Hockey Ireland Cork Hockey Storage €35,280 Munster Cricket Union CLG Increase facility standards in Munster Cork Cricket €29,949 Munster Kart Club Equipment Cork Motor Sport €2,700 Donegal County Camogie Donegal Senior camogie Donegal Camogie €1,442 Donegal LGFA Sports Equipment & Kits for Donegal LGFA Donegal Ladies Gaelic Football €8,005 ChildVision Ltd sports equipment for ChildVision Dublin Equestrian Sports €30,009 Cricket Leinster (trading name of The Cricket Leinster 2020/2021 Equipment Dublin Cricket Leinster Cricket Union CLG) Application €1,812 Irish Harness Racing Association CLG Extension of IHRA Integration Programme Dublin Equestrian Sports €29,354 Irish Homeless Street Leagues Sports Equipment Dublin Soccer €5,474 Leinster -

Revised-Fixture-Booklet2020.Pdf

Armagh County Board, Athletic Grounds, Dalton Road, Armagh, BT60 4AE. Fón: 02837 527278. Office Hrs: Mon-Fri 9AM – 5PM. Closed Daily 1PM – 2PM. CONTENTS Oifigigh An Choiste Contae 1-5 Armagh GAA Staff 6-7 GAA & Provincial Offices 8 Media 9 County Sub Committees 10-11 Club Contacts 12-35 2020 Adult Referees 36-37 County Bye-Laws 38-46 2020 Amended Football & League Reg 47-59 Championship Regulations 60-69 County Fixtures Oct 2020 – Dec 2020 70-71 Club Fixtures 72-94 OIFIGIGH AN CHOISTE CONTAE CATHAOIRLEACH Mícheál Ó Sabhaois (Michael Savage) Fón: 07808768722 Email: [email protected] LEAS CATHAOIRLEACH Séamus Mac Aoidh (Jimmy McKee) Fón: 07754603867 Email: [email protected] RÚNAÍ Seán Mac Giolla Fhiondain (Sean McAlinden) Fón: 07760440872 Email: [email protected] LEAS RÚNAÍ Léana Uí Mháirtín (Elena Martin) Fón: 07880496123 Email: [email protected] CISTEOIR Gearard Mac Daibhéid (Gerard Davidson) Fón: 07768274521 Email: [email protected] Page | 1 CISTEOIR CÚNTA Tomas O hAdhmaill (Thomas Hamill) Fón: 07521366446 Email: [email protected] OIFIGEACH FORBARTHA Liam Rosach (Liam Ross) Fón: 07720321799 Email: [email protected] OIFIGEACH CULTÚIR Barra Ó Muirí Fón: 07547306922 Email: [email protected] OIFIGEACH CAIDRIMH PHOIBLÍ Clár Ní Siail (Claire Shields) Fón: 07719791629 Email: [email protected] OIFIGEACH IOMANA Daithi O’Briain (David O Brien) Fón: 07775176614 Email: [email protected] TEACHTA CHOMHAIRLE ULADH 1 Pádraig Ó hEachaidh (Padraig -

Irish Responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919-1932 Author(s) Phelan, Mark Publication Date 2013-01-07 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/3401 Downloaded 2021-09-27T09:47:44Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh Department of History School of Humanities National University of Ireland, Galway December 2012 ABSTRACT This project assesses the impact of the first fascist power, its ethos and propaganda, on key constituencies of opinion in the Irish Free State. Accordingly, it explores the attitudes, views and concerns expressed by members of religious organisations; prominent journalists and academics; government officials/supporters and other members of the political class in Ireland, including republican and labour activists. By contextualising the Irish response to Fascist Italy within the wider patterns of cultural, political and ecclesiastical life in the Free State, the project provides original insights into the configuration of ideology and social forces in post-independence Ireland. Structurally, the thesis begins with a two-chapter account of conflicting confessional responses to Italian Fascism, followed by an analysis of diplomatic intercourse between Ireland and Italy. Next, the thesis examines some controversial policies pursued by Cumann na nGaedheal, and assesses their links to similar Fascist initiatives. The penultimate chapter focuses upon the remarkably ambiguous attitude to Mussolini’s Italy demonstrated by early Fianna Fáil, whilst the final section recounts the intensely hostile response of the Irish labour movement, both to the Italian regime, and indeed to Mussolini’s Irish apologists. -

![Études Irlandaises, 37-1 | 2012 [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 30 Juin 2014, Consulté Le 24 Septembre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1674/%C3%A9tudes-irlandaises-37-1-2012-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-30-juin-2014-consult%C3%A9-le-24-septembre-2020-631674.webp)

Études Irlandaises, 37-1 | 2012 [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 30 Juin 2014, Consulté Le 24 Septembre 2020

Études irlandaises 37-1 | 2012 Varia Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/2927 DOI : 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.2927 ISSN : 2259-8863 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Caen Édition imprimée Date de publication : 30 juin 2012 ISSN : 0183-973X Référence électronique Études irlandaises, 37-1 | 2012 [En ligne], mis en ligne le 30 juin 2014, consulté le 24 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/2927 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ etudesirlandaises.2927 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 24 septembre 2020. Études irlandaises est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. 1 SOMMAIRE Études d'histoire et de civilisation « Les Irlandais attendent avec une légère impatience » : Paris et la demande d’adhésion de Dublin à la CEE, 1961-1973 Christophe Gillissen German Invasion and Spy Scares in Ireland, 1890s-1914: Between Fiction and Fact Jérôme Aan de Wiel Magdalen Laundries : enjeu des droits de l’homme et responsabilité publique Nathalie Sebbane Mobilisation nationale et solidarité internationale : les syndicats en Irlande et la question du Moyen-Orient Marie-Violaine Louvet “Deposited Elsewhere”: The Sexualized Female Body and the Modern Irish Landscape Cara Delay Art et Image “Doesn’t Mary Have a Lovely Bottom?”: Gender, Sexuality and Catholic Ideology in Father Ted Lisa McGonigle Études littéraires Fair Game? James Joyce, Sean O’Casey, and -

Gaelic Football in Cleveland: Early Days

Gaelic Football in Cleveland: Early Days The Gaelic Athletic Association was founded on November 1, 1884, in County Tipperary, Ireland, to set standards for and invigorate the playing of traditional Irish sports. References in the mainstream American press to Gaelic football matches--at the Pan American games in Buffalo in 1901, the World’s Fair in St. Louis in 1903 and under the auspices of the US Army in 1917— serve as reminders that Irish immigrants brought their passion for Gaelic games with them to the United States. Mention of Gaelic football surfaces in Cleveland newspapers in the 1920s. The close connection between the GAA and the cause of Irish nationalism was heightened by events of the day; in 1920, the Royal Irish Constabulary killed twelve spectators and a player at a Gaelic football match in Croke Park in Dublin. At an Irish picnic held in Cleveland in 1920, to express solidarity with nationalist hunger striker Terence MacSwiney, a Gaelic football match featured prominently. As reported in the Plain Dealer, the players “had starred in the game in their native land and [wished] to perpetuate the game in the United States by engaging in contests under Gaelic rules with teams from other cities.” Throughout the 1920s, various groups--the Young Ireland Gaelic Football team, a Municipal Gaelic Football Association, and the Cleveland Gaelic Football league—make fleeting appearances in Cleveland’s newspapers, often associated with the name of Phil McGovern as organizer. But it proved difficult to find enough players for teams and competition on a consistent basis. In Cleveland, Gaelic football players also found an outlet in soccer, even though playing soccer or other “British” games was anathema to the GAA in Ireland. -

A History of the GAA from Cú Chulainn to Shefflin Education Department, GAA Museum, Croke Park How to Use This Pack Contents

Primary School Teachers Resource Pack A History of The GAA From Cú Chulainn to Shefflin Education Department, GAA Museum, Croke Park How to use this Pack Contents The GAA Museum is committed to creating a learning 1 The GAA Museum for Primary Schools environment and providing lifelong learning experiences which are meaningful, accessible, engaging and stimulating. 2 The Legend of Cú Chulainn – Teacher’s Notes The museum’s Education Department offers a range of learning 3 The Legend of Cú Chulainn – In the Classroom resources and activities which link directly to the Irish National Primary SESE History, SESE Geography, English, Visual Arts and 4 Seven Men in Thurles – Teacher’s Notes Physical Education Curricula. 5 Seven Men in Thurles – In the Classroom This resource pack is designed to help primary school teachers 6 Famous Matches: Bloody Sunday 1920 – plan an educational visit to the GAA Museum in Croke Park. The Teacher’s Notes pack includes information on the GAA Museum primary school education programme, along with ten different curriculum 7 Famous Matches: Bloody Sunday 1920 – linked GAA topics. Each topic includes teacher’s notes and In the Classroom classroom resources that have been chosen for its cross 8 Famous Matches: Thunder and Lightning Final curricular value. This resource pack contains everything you 1939 – Teacher’s Notes need to plan a successful, engaging and meaningful visit for your class to the GAA Museum. 9 Famous Matches: Thunder and Lightning Final 1939 – In the Classroom Teacher’s Notes 10 Famous Matches: New York Final 1947 – Teacher’s Notes provide background information on an Teacher’s Notes assortment of GAA topics which can be used when devising a lesson plan.