Celestial Navigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ast 443 / Phy 517

AST 443 / PHY 517 Astronomical Observing Techniques Prof. F.M. Walter I. The Basics The 3 basic measurements: • WHERE something is • WHEN something happened • HOW BRIGHT something is Since this is science, let’s be quantitative! Where • Positions: – 2-dimensional projections on celestial sphere (q,f) • q,f are angular measures: radians, or degrees, minutes, arcsec – 3-dimensional position in space (x,y,z) or (q, f, r). • (x,y,z) are linear positions within a right-handed rectilinear coordinate system. • R is a distance (spherical coordinates) • Galactic positions are sometimes presented in cylindrical coordinates, of galactocentric radius, height above the galactic plane, and azimuth. Angles There are • 360 degrees (o) in a circle • 60 minutes of arc (‘) in a degree (arcmin) • 60 seconds of arc (“) in an arcmin There are • 24 hours (h) along the equator • 60 minutes of time (m) per hour • 60 seconds of time (s) per minute • 1 second of time = 15”/cos(latitude) Coordinate Systems "What good are Mercator's North Poles and Equators Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?" So the Bellman would cry, and the crew would reply "They are merely conventional signs" L. Carroll -- The Hunting of the Snark • Equatorial (celestial): based on terrestrial longitude & latitude • Ecliptic: based on the Earth’s orbit • Altitude-Azimuth (alt-az): local • Galactic: based on MilKy Way • Supergalactic: based on supergalactic plane Reference points Celestial coordinates (Right Ascension α, Declination δ) • δ = 0: projection oF terrestrial equator • (α, δ) = (0,0): -

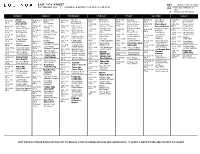

E a S T 7 4 T H S T R E E T August 2021 Schedule

E A S T 7 4 T H S T R E E T KEY St udi o key on bac k SEPT EM BER 2021 SC H ED U LE EF F EC T IVE 09.01.21–09.30.21 Bolld New Class, Instructor, or Time ♦ Advance sign-up required M O NDA Y T UE S DA Y W E DNE S DA Y T HURS DA Y F RII DA Y S A T URDA Y S UNDA Y Atthllettiic Master of One Athletic 6:30–7:15 METCON3 6:15–7:00 Stacked! 8:00–8:45 Cycle Beats 8:30–9:30 Vinyasa Yoga 6:15–7:00 6:30–7:15 6:15–7:00 Condiittiioniing Gerard Conditioning MS ♦ Kevin Scott MS ♦ Steve Mitchell CS ♦ Mike Harris YS ♦ Esco Wilson MS ♦ MS ♦ MS ♦ Stteve Miittchellll Thelemaque Boyd Melson 7:00–7:45 Cycle Power 7:00–7:45 Pilates Fusion 8:30–9:15 Piillattes Remiix 9:00–9:45 Cardio Sculpt 6:30–7:15 Cycle Beats 7:00–7:45 Cycle Power 6:30–7:15 Cycle Power CS ♦ Candace Peterson YS ♦ Mia Wenger YS ♦ Sammiie Denham MS ♦ Cindya Davis CS ♦ Serena DiLiberto CS ♦ Shweky CS ♦ Jason Strong 7:15–8:15 Vinyasa Yoga 7:45–8:30 Firestarter + Best Firestarter + Best 9:30–10:15 Cycle Power 7:15–8:05 Athletic Yoga Off The Barre Josh Mathew- Abs Ever 9:00–9:45 CS ♦ Jason Strong 7:00–8:00 Vinyasa Yoga 7:00–7:45 YS ♦ MS ♦ MS ♦ Abs Ever YS ♦ Elitza Ivanova YS ♦ Margaret Schwarz YS ♦ Sarah Marchetti Meier Shane Blouin Luke Bernier 10:15–11:00 Off The Barre Gleim 8:00–8:45 Cycle Beats 7:30–8:15 Precision Run® 7:30–8:15 Precision Run® 8:45–9:45 Vinyasa Yoga Cycle Power YS ♦ Cindya Davis Gerard 7:15–8:00 Precision Run® TR ♦ Kevin Scott YS ♦ Colleen Murphy 9:15–10:00 CS ♦ Nikki Bucks TR ♦ CS ♦ Candace 10:30–11:15 Atletica Thelemaque TR ♦ Chaz Jackson Peterson 8:45–9:30 Pilates Fusion 8:00–8:45 -

Captain Vancouver, Longitude Errors, 1792

Context: Captain Vancouver, longitude errors, 1792 Citation: Doe N.A., Captain Vancouver’s longitudes, 1792, Journal of Navigation, 48(3), pp.374-5, September 1995. Copyright restrictions: Please refer to Journal of Navigation for reproduction permission. Errors and omissions: None. Later references: None. Date posted: September 28, 2008. Author: Nick Doe, 1787 El Verano Drive, Gabriola, BC, Canada V0R 1X6 Phone: 250-247-7858, FAX: 250-247-7859 E-mail: [email protected] Captain Vancouver's Longitudes – 1792 Nicholas A. Doe (White Rock, B.C., Canada) 1. Introduction. Captain George Vancouver's survey of the North Pacific coast of America has been characterized as being among the most distinguished work of its kind ever done. For three summers, he and his men worked from dawn to dusk, exploring the many inlets of the coastal mountains, any one of which, according to the theoretical geographers of the time, might have provided a long-sought-for passage to the Atlantic Ocean. Vancouver returned to England in poor health,1 but with the help of his brother John, he managed to complete his charts and most of the book describing his voyage before he died in 1798.2 He was not popular with the British Establishment, and after his death, all of his notes and personal papers were lost, as were the logs and journals of several of his officers. Vancouver's voyage came at an interesting time of transition in the technology for determining longitude at sea.3 Even though he had died sixteen years earlier, John Harrison's long struggle to convince the Board of Longitude that marine chronometers were the answer was not quite over. -

Basic Principles of Celestial Navigation James A

Basic principles of celestial navigation James A. Van Allena) Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242 ͑Received 16 January 2004; accepted 10 June 2004͒ Celestial navigation is a technique for determining one’s geographic position by the observation of identified stars, identified planets, the Sun, and the Moon. This subject has a multitude of refinements which, although valuable to a professional navigator, tend to obscure the basic principles. I describe these principles, give an analytical solution of the classical two-star-sight problem without any dependence on prior knowledge of position, and include several examples. Some approximations and simplifications are made in the interest of clarity. © 2004 American Association of Physics Teachers. ͓DOI: 10.1119/1.1778391͔ I. INTRODUCTION longitude ⌳ is between 0° and 360°, although often it is convenient to take the longitude westward of the prime me- Celestial navigation is a technique for determining one’s ridian to be between 0° and Ϫ180°. The longitude of P also geographic position by the observation of identified stars, can be specified by the plane angle in the equatorial plane identified planets, the Sun, and the Moon. Its basic principles whose vertex is at O with one radial line through the point at are a combination of rudimentary astronomical knowledge 1–3 which the meridian through P intersects the equatorial plane and spherical trigonometry. and the other radial line through the point G at which the Anyone who has been on a ship that is remote from any prime meridian intersects the equatorial plane ͑see Fig. -

Printable Celestial Navigation Work Forms

S T A R P A T H ® S c h o o l o f N a v i g a t i o n PRINTABLE CELESTIAL NAVIGATION WORK FORMS For detailed instructions and numerical examples, see the companion booklet listed below. FORM 104 — All bodies, using Pub 249 or Pub 229 FORM 106 — All Bodies, Using NAO Tables FORM 108 — All Bodies, Almanac, and NAO Tables FORM 109 — Solar Index Correction FORM 107 — Latitude at LAN FORM 110 — Latitude by Polaris FORM 117 — Lat, Lon at LAN plus Polaris FORM 111 — Pub 249, Vol. 1 Selected Stars Other Starpath publications on Celestial Navigation Celestial Navigation Starpath Celestial Navigation Work Forms Hawaii by Sextant How to Use Plastic Sextants The Star Finder Book GPS Backup with a Mark 3 Sextant Emergency Navigation Stark Tables for Clearing the Lunar Distance Long Term Almanac 2000 to 2050 Celestial Navigation Work Form Form 104, All Sights, Pub. 249 or Pub. 229 WT h m s date body Hs ° ´ WE DR log index corr. 1 +S -F Lat + off - on ZD DR HE DIP +W -E Lon ft - UTC h m s UTC date / LOP label Ha ° ´ GHA v Dec d HP ° ´ moon ° ´ + 2 hr. planets hr - moon GHA + d additional ° ´ + ´ altitude corr. m.s. corr. - moon, mars, venus 3 SHA + stars Dec Dec altitude corr. or ° ´ or ° ´ all sights v corr. moon, planets min GHA upper limb moon ° ´ tens d subtract 30’ d upper Ho units d ° ´ a-Lon ° ´ d lower -W+E dsd dsd T LHA corr. + Hc 00´ W / 60´ E ° d. -

Understanding Celestial Navigation by Ron Davidson, SN Poverty Bay Sail & Power Squadron

Understanding Celestial Navigation by Ron Davidson, SN Poverty Bay Sail & Power Squadron I grew up on the Jersey Shore very near the entrance to New York harbor and was fascinated by the comings and goings of the ships, passing the Ambrose and Scotland light ships that I would watch from my window at night. I wondered how these mariners could navigate these great ships from ports hundreds or thousands of miles distant and find the narrow entrance to New York harbor. Celestial navigation was always shrouded in mystery that so intrigued me that I eventually began a journey of discovery. One of the most difficult tasks for me, after delving into the arcane knowledge presented in most reference books on the subject, was trying to formulate the “big picture” of how celestial navigation worked. Most texts were full of detailed "cookbook" instructions and mathematical formulas teaching the mechanics of sight reduction and how to use the almanac or sight reduction tables, but frustratingly sparse on the overview of the critical scientific principles of WHY and HOW celestial works. My end result was that I could reduce a sight and obtain a Line of Position but I was unsatisfied not knowing “why” it worked. This article represents my efforts at learning and teaching myself 'celestial' and is by no means comprehensive. As a matter of fact, I have purposely ignored significant detail in order to present the big picture of how celestial principles work so as not to clutter the mind with arcane details and too many magical formulas. The USPS JN & N courses will provide all the details necessary to ensure your competency as a celestial navigator. -

The Mathematics of the Chinese, Indian, Islamic and Gregorian Calendars

Heavenly Mathematics: The Mathematics of the Chinese, Indian, Islamic and Gregorian Calendars Helmer Aslaksen Department of Mathematics National University of Singapore [email protected] www.math.nus.edu.sg/aslaksen/ www.chinesecalendar.net 1 Public Holidays There are 11 public holidays in Singapore. Three of them are secular. 1. New Year’s Day 2. Labour Day 3. National Day The remaining eight cultural, racial or reli- gious holidays consist of two Chinese, two Muslim, two Indian and two Christian. 2 Cultural, Racial or Religious Holidays 1. Chinese New Year and day after 2. Good Friday 3. Vesak Day 4. Deepavali 5. Christmas Day 6. Hari Raya Puasa 7. Hari Raya Haji Listed in order, except for the Muslim hol- idays, which can occur anytime during the year. Christmas Day falls on a fixed date, but all the others move. 3 A Quick Course in Astronomy The Earth revolves counterclockwise around the Sun in an elliptical orbit. The Earth ro- tates counterclockwise around an axis that is tilted 23.5 degrees. March equinox June December solstice solstice September equinox E E N S N S W W June equi Dec June equi Dec sol sol sol sol Beijing Singapore In the northern hemisphere, the day will be longest at the June solstice and shortest at the December solstice. At the two equinoxes day and night will be equally long. The equi- noxes and solstices are called the seasonal markers. 4 The Year The tropical year (or solar year) is the time from one March equinox to the next. The mean value is 365.2422 days. -

Calculating Percentages for Time Spent During Day, Week, Month

Calculating Percentages of Time Spent on Job Responsibilities Instructions for calculating time spent during day, week, month and year This is designed to help you calculate percentages of time that you perform various duties/tasks. The figures in the following tables are based on a standard 40 hour work week, 174 hour work month, and 2088 hour work year. If a recurring duty is performed weekly and takes the same amount of time each week, the percentage of the job that this duty represents may be calculated by dividing the number of hours spent on the duty by 40. For example, a two-hour daily duty represents the following percentage of the job: 2 hours x 5 days/week = 10 total weekly hours 10 hours / 40 hours in the week = .25 = 25% of the job. If a duty is not performed every week, it might be more accurate to estimate the percentage by considering the amount of time spent on the duty each month. For example, a monthly report that takes 4 hours to complete represents the following percentage of the job: 4/174 = .023 = 2.3%. Some duties are performed only certain times of the year. For example, budget planning for the coming fiscal year may take a week and a half (60 hours) and is a major task, but this work is performed one time a year. To calculate the percentage for this type of duty, estimate the total number of hours spent during the year and divide by 2088. This budget planning represents the following percentage of the job: 60/2088 = .0287 = 2.87%. -

How Long Is a Year.Pdf

How Long Is A Year? Dr. Bryan Mendez Space Sciences Laboratory UC Berkeley Keeping Time The basic unit of time is a Day. Different starting points: • Sunrise, • Noon, • Sunset, • Midnight tied to the Sun’s motion. Universal Time uses midnight as the starting point of a day. Length: sunrise to sunrise, sunset to sunset? Day Noon to noon – The seasonal motion of the Sun changes its rise and set times, so sunrise to sunrise would be a variable measure. Noon to noon is far more constant. Noon: time of the Sun’s transit of the meridian Stellarium View and measure a day Day Aday is caused by Earth’s motion: spinning on an axis and orbiting around the Sun. Earth’s spin is very regular (daily variations on the order of a few milliseconds, due to internal rearrangement of Earth’s mass and external gravitational forces primarily from the Moon and Sun). Synodic Day Noon to noon = synodic or solar day (point 1 to 3). This is not the time for one complete spin of Earth (1 to 2). Because Earth also orbits at the same time as it is spinning, it takes a little extra time for the Sun to come back to noon after one complete spin. Because the orbit is elliptical, when Earth is closest to the Sun it is moving faster, and it takes longer to bring the Sun back around to noon. When Earth is farther it moves slower and it takes less time to rotate the Sun back to noon. Mean Solar Day is an average of the amount time it takes to go from noon to noon throughout an orbit = 24 Hours Real solar day varies by up to 30 seconds depending on the time of year. -

The Determination of Longitude in Landsurveying.” by ROBERTHENRY BURNSIDE DOWSES, Assoc

316 DOWNES ON LONGITUDE IN LAXD SUIWETISG. [Selected (Paper No. 3027.) The Determination of Longitude in LandSurveying.” By ROBERTHENRY BURNSIDE DOWSES, Assoc. M. Inst. C.E. THISPaper is presented as a sequel tothe Author’s former communication on “Practical Astronomy as applied inLand Surveying.”’ It is not generally possible for a surveyor in the field to obtain accurate determinationsof longitude unless furnished with more powerful instruments than is usually the case, except in geodetic camps; still, by the methods here given, he may with care obtain results near the truth, the error being only instrumental. There are threesuch methods for obtaining longitudes. Method 1. By Telrgrcrph or by Chronometer.-In either case it is necessary to obtain the truemean time of the place with accuracy, by means of an observation of the sun or z star; then, if fitted with a field telegraph connected with some knownlongitude, the true mean time of that place is obtained by telegraph and carefully compared withthe observed true mean time atthe observer’s place, andthe difference between thesetimes is the difference of longitude required. With a reliable chronometer set totrue Greenwich mean time, or that of anyother known observatory, the difference between the times of the place and the time of the chronometer must be noted, when the difference of longitude is directly deduced. Thisis the simplest method where a camp is furnisl~ed with eitherof these appliances, which is comparatively rarely the case. Method 2. By Lunar Distances.-This observation is one requiring great care, accurately adjusted instruments, and some littleskill to obtain good results;and the calculations are somewhat laborious. -

Equation of Time — Problem in Astronomy M

This paper was awarded in the II International Competition (1993/94) "First Step to Nobel Prize in Physics" and published in the competition proceedings (Acta Phys. Pol. A 88 Supplement, S-49 (1995)). The paper is reproduced here due to kind agreement of the Editorial Board of "Acta Physica Polonica A". EQUATION OF TIME | PROBLEM IN ASTRONOMY M. Muller¨ Gymnasium M¨unchenstein, Grellingerstrasse 5, 4142 M¨unchenstein, Switzerland Abstract The apparent solar motion is not uniform and the length of a solar day is not constant throughout a year. The difference between apparent solar time and mean (regular) solar time is called the equation of time. Two well-known features of our solar system lie at the basis of the periodic irregularities in the solar motion. The angular velocity of the earth relative to the sun varies periodically in the course of a year. The plane of the orbit of the earth is inclined with respect to the equatorial plane. Therefore, the angular velocity of the relative motion has to be projected from the ecliptic onto the equatorial plane before incorporating it into the measurement of time. The math- ematical expression of the projection factor for ecliptic angular velocities yields an oscillating function with two periods per year. The difference between the extreme values of the equation of time is about half an hour. The response of the equation of time to a variation of its key parameters is analyzed. In order to visualize factors contributing to the equation of time a model has been constructed which accounts for the elliptical orbit of the earth, the periodically changing angular velocity, and the inclined axis of the earth. -

Pulsarplane D5.4 Final Report

NLR-CR-2015-243-PT16 PulsarPlane D5.4 Final Report Authors: H. Hesselink, P. Buist, B. Oving, H. Zelle, R. Verbeek, A. Nooroozi, C. Verhoeven, R. Heusdens, N. Gaubitch, S. Engelen, A. Kestilä, J. Fernandes, D. Brito, G. Tavares, H. Kabakchiev, D. Kabakchiev, B. Vasilev, V. Behar, M. Bentum Customer EC Contract number ACP2-GA-2013-335063 Owner PulsarPlane consortium Classification Public Date July 2015 PROJECT FINAL REPORT Grant Agreement number: 335063 Project acronym: PulsarPlane Project title: PulsarPlane Funding Scheme: FP7 L0 Period covered: from September 2013 to May 2015 Name of the scientific representative of the project's co-ordinator, Title and Organisation: H.H. (Henk) Hesselink Sr. R&D Engineer National Aerospace Laboratory, NLR Tel: +31.88.511.3445 Fax: +31.88.511.3210 E-mail: [email protected] Project website address: www.pulsarplane.eu Summary Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Structure of the document 4 1.2 Acknowledgements 4 2 Final publishable summary report 5 2.1 Executive summary 5 2.2 Summary description of project context and objectives 6 2.2.1 Introduction 6 2.2.2 Description of PulsarPlane concept 6 2.2.3 Detection 8 2.2.4 Navigation 8 2.3 Main S&T results/foregrounds 9 2.3.1 Navigation based on signals from radio pulsars 9 2.3.2 Pulsar signal simulator 11 2.3.3 Antenna 13 2.3.4 Receiver 15 2.3.5 Signal processing 22 2.3.6 Navigation 24 2.3.7 Operating a pulsar navigation system 30 2.3.8 Performance 31 2.4 Potential impact and the main dissemination activities and exploitation of results 33 2.4.1 Feasibility 34 2.4.2 Costs, benefits and impact 35 2.4.3 Environmental impact 36 2.5 Public website 37 2.6 Project logo 37 2.7 Diagrams or photographs illustrating and promoting the work of the project 38 2.8 List of all beneficiaries with the corresponding contact names 39 3 Use and dissemination of foreground 41 4 Report on societal implications 46 5 Final report on the distribution of the European Union financial contribution 53 1 Introduction This document is the final report of the PulsarPlane project.