Methodology of Creating a Neighborhood Where Identity Can Evolve Applied Design Scenario in Makiki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: __Earle Ernst Residence ____________ Other names/site number: __ Samuel Elbert Residence______ ____ Name of related multiple property listing: ___________________N/A_ ________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: ___3293 Huelani Drive ___________________________________ City or town: ___Honolulu____ State: __Hawaii_______ County: __Honolulu_______ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS APRIL 1985 VOL. XXIX NO.2 SAH NOTICES Street, New York, NY 10025. The Preservation and Resto 1985 Annual Meeting-Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (April 17- ration of State Capitols, chaired by Dennis McFadden, 21). Osmund Overby is general chairman of the meeting. Temporary State Commission on the Restoration of the Franklin Toker, University of Pittsburgh and Richard Capitol, Alfred E. Smith Office Building, P.O. Box 7016, Cleary, Carnegie Mellon University, are local chairmen. Albany, NY 12225. Plan and Function in Palaces and Palatial Houses from the Fourteenth through the Seven 1986 Annual Meeting-Washington, D.C. (April 2-6). Gener teenth Centuries, chaired by Patricia Waddy, School of al chairman of the meeting is Osmund Overby of the Architecture, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 13210. University of Missouri. Antoinette Lee, Columbia Histori In addition, there will be workshops and discussions as cal Society, is serving as local chairman. Session titles and follows: chairmen are: Architectural Measured Drawings for Historic Structures, Thursday morning, April3: General Session, chaired by Wednesday, April2, sponsored jointly with the Association Damie Stillman, Department of Art History, University of of Collegiate Schools of Architecture and the Historic Delaware, Newark, DE 19716. Modern Architecture, American Buildings Survey, for further information, write chaired by Norma Evenson, Department of Architecture, John A. Burns, Historic American Buildings Survey, Na University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720. Rules of tional Park Service, P.O. Box 37127, Washington, D.C. Thumb: The Unwritten Design Traditions of Master Masons, 20013-7127. Architectural Records: Progress Towards Surveyors, Carpenters, Builders, and the Like, chaired by Access, for further information, write Mary Ison, Prints Nicholas Adams, Department of Art and Architecture, and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA 18015. -

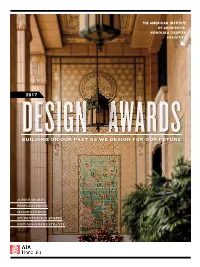

Design Awards 2017 Is Published by Hawaii Business Magazine, in Partnership with AIA Honolulu, October 2017

THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS, HONOLULU CHAPTER PRESENTS DESIGN2017 AWARDS BUILDING ON OUR PAST AS WE DESIGN FOR OUR FUTURE JURIED AWARDS PEOPLE’S CHOICE MAYOR’S CHOICE STUDENT DESIGN AWARDS DISTINGUISHED ENTRANTS Helping Our Clients Succeed Every Step of the Way. I appreciate the partnership with Swinerton throughout the project and even past the opening. The team was always responsive to our needs and had a big part in creating this unique and beautiful property. Robert Friedl General Manager The Laylow, Pyramid Hotel Group REGGIE CASTILLO Superintendent Swinerton Builders ROBERT FRIEDL General Manager, The Laylow, NICK WACHI Pyramid Hotel Group Project Manager Swinerton Builders Envision the Possibilities. A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF AIA HONOLULU 2017 DESIGN AWARDS In 1926 TABLE OF six pioneering architects, Hart Wood, Charles W. Dickey, Walter L. Emory, CONTENTS Marshal H. Webb, Ralph Fishbourne, and Edwin Pettit wrote to the American Institute of Architects (AIA) requesting to charter a local Chapter. On October 13, 1926, a charter was President’s Message granted from the AIA to form the Hawaii 5 Meet the Jurors Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. Today, the American Institute of Architects, through the AIA Mahalo to Our Sponsors Hawaii State Council, AIA Maui and 7 Project Categories & Award Levels AIA Honolulu chapters, continues to represent the interests of AIA members AWARD OF EXCELLENCE throughout Hawaii. 8 This year, the AIA Honolulu Chapter commemorates our founding members AWARDS OF MERIT through the 2017 Design Awards Program 10 as we celebrate over 90 years as an organization in Hawaii. As we pay tribute HONORABLE MENTIONS to our foundation and roots, we must 13 also recognize the new diversity of our growing organization, including cultural, MAYOR’S CHOICE AWARD gender and generational diversity, and PEOPLE’S CHOICE AWARD how each architect and member is 17 continually adapting and contributing to the needs of our community. -

Hawaii Capital Historic District Is an Area That Defines the Central Nexus of Honolulu

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) = UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLAGES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ [NAME HISTORIC AND/OR COMMON Hawaii Gapital Historic District LOCATION STREET & NUMBER As described in district description i ; ^.-A ...< ,s , .,, .',,,«, r\i.v .- J> '-- :'----.^^ 4 ' _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL'i DISTRICT Honolulu ___.VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Hawaii Honolulu 003 <-"' HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP "V STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT .^.PUBLIC :£±OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE .^MUSEUM JfeuiLDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^COMMERCIAL _PARK y —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ^—PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS I —OBJECT —IN PROCESS ^YES: RESTRICTED -f±GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: Various: Individual site forms included STREET & NUMBER Various: Individual site forms included CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. __ Bureau of Conveyances STREET & NUMBER 465 South King Street CITY, TOWN STATE Honolulu Hawaii fl'TLE Hawaii Register of Historic Places - Site #80-14-1321 DATE FEDERAL ^LSTATE COUNTY LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Hawaii Register_ojLJ3_isjtQris_ Places CITY, TOWN STATE Honolulu Hawaii DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE -

Brenda Lam 2512 Manoa Rd. Honolulu, Hawaii 96822

Brenda Lam 2512 Manoa Rd. Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Date: November 2, 2016 To: Review Board for Hawaii Register of Historic Places Dear Board Members, I am resubmitting application LOG No. 201600829, DOC No. 1607MB08: Hart Wood Residence. I am both the owner and preparer of the application for the Hart Wood Residence. I am resubmitting my application to be reviewed at the December 9, 2016 meeting. My original application was reviewed on the agenda of the Historic Places Review Board meeting on August 26, 2016. My application was deferred due to the following: 1. Board requested adding Criterion B- Property is associated with the lives of persons significant in our past. 2. Board requested a floor plan of the second story of the residence. 3. Board inquired why photographs of the upstairs were not included in the application. 4. Board requested further inspection of the second story, beyond viewing the interior staircase and window (which were viewed) which I felt were significant to my application as superior craftsmanship. 5. Board requested adding four elevations of the exterior of the home. These could be sketches, or formal architectural drawings. I am therefore resubmitting the application for reconsideration to be placed on the Hawaii Register of Historic Places. In my revised application I have found new information which is critical to my application and that will be included. I am adding Criterion B, and making the appropriate re-write of the application. I am including a second story floor plan. 1 I am adding five photographs of the upstairs which show the condition of the second floor space prior to roommate moving in. -

Historic Downtown Honolulu

Dillingham Transpor- Hawaiian Electric Hawaii State Library tation Building (1929) Building (1927) (1913) The Mediterranean/ This four-story building is The library’s construc- 11Italian Renaissance style build- 16characteristic of an early 18th 21tion was made possible through ing was designed by architect century Spanish form that features a gift from industrialist Andrew Lincoln Rogers. The building half-stilted arched windows with Carnegie. The Greco-Roman style Historic consists of three wings connected by a covered Churriguera -decorated column supports, a corner building was designed by Henry Witchfi eld and still arcade and spans from Queen Street to Ala Moana cupola and a low-rise, polygonal tiled roof. The serves today as the downtown branch of the Hawaii Boulevard. It features an Art Deco lobby, painted building was designed by York and Sawyer with State Public Library. high ceilings, and a classical cornice. construction overseen by Emory and Webb. Downtown Honolulu Hale (1929) – FINISH LINE Alexander & Baldwin YWCA Building (1927) Designed by Dickey, Wood and others, Building (1929) The fi rst structure in Ha- this Spanish mission style building features open-to-the-sky courtyards, hand-painted Honolulu A design colabora- waii designed completely 22 12tion between Charles W. Dickey 17by a woman. Julia Morgan, known ceiling frescos, 1,500-pound bronze front doors, and and Hart Wood. The building is for her work on Hearst Castle, 4,500-pound courtyard chandeliers. The main entry a unique fusion of eastern designed the building in Spanish, faces King Street, behind a zig-zag pattern of planters and western design elements that features a dou- Colonial and Mediterranean styles. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: _George R. Ward House __________________________ Other names/site number: _Seymour House _____________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: _N/A__________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _2438 Ferdinand Ave__________________________________________ City or town: Honolulu __________ State: _Hawaii__________ County: Honolulu _______ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for -

Official Guide of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, 1915 : San

OtpicialGuipe PANAAA - PACIFIC I NTERNATIONAL EXPOSITION SAN FRANCISCO 19IS W, A Cordial Welcome Awaits You at the Westinghouse Electric Exhibits in The Palace of Transportation The Palace of Machinery The Mine—Palace of Mines and Metallurgy □ □□ Westinghouse Electric products are to be found throughout the Exposition Grounds in the Exhibit Palaces, Nation Buildings, State Buildings, and the “Zone.” Westinghouse Electric achievements have made large Expositions possible. Its devices generate electric energy; transmit this energy long distances to you; haul trains; operate the street cars in which you ride; light your city; convey minerals from vein to surface; drive ma¬ chinery in every kind of factory; bring assistance and comfort to your home; start and light your motor ^ar; drive your electric pleasure vehicle- and do a multitude of other things. Such devices can be seen in these exhibits. See them, and when you buy- Specify Westinghouse Electric Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Co. East Pittsburg, Pa. U. S. A. Sales Offices in 45 American Cities Tin c* TtnciH/^ Ttntn the only hotel with. X ilU lllOlUC XI 111 IN THE GROUNDS OF THE Panama-Pacific International Exposition QPENI NG January 15, 1915. Absolute fire protection. Individual rates $1.00 to $5j00 per day, European plan. American plan rates added. Restaurants and Cafes. All outside rooms have private baths. Telephone in each room. Steam heated throughout. Convention and Banquet Halls for large gatherings._ Under the Supervision of the Exposition Management Exposition B'dg. TheWdlrnn4" Make Your Reservations NOW San Francisco “BOSSY BRAND” MILK In Bottles—Not Canned. Noted for Its Rich, Pure Flavor. -

Reppun House

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: ________Dr. Carl and Emily Reppun Residence ________________ Other names/site number: __ ____ Name of related multiple property listing: ___________________N/A_ ________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: ___2874 Komaia Place ___________________________________ City or town: ___Honolulu____ State: __Hawaii_______ County: __Honolulu_______ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Guard, J.B. House______________ Other names/site number: Lippman House (TMK: (1) 3-9-003:004) Name of related multiple property listing: N/A . (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing _______________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 305A Portlock Road________________________________________ City or town: Honolulu _______ State: Hawaii__________ County: Honolulu________ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ______________________________________________________ ______________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews The First Strange Place: The Alchemy of Race and Sex in World War II Hawaii. By Beth Bailey and David Farber. New York: The Free Press, 1992. ix + 270 pp. Illustrated. Notes. Index. $22.95. The exotic—coconut palms and white sand beaches, tawny-skinned and almost naked young women, something called "Aloooooha!"—has long been the staple of Hawai'i's tourist industry. During World War II, however, the islands' visitors did not come voluntarily, and while some expected the exotic, others didn't know what to expect. They were frightened young men, drafted by their country to fight Hiro- hito. Many had never strayed fifty miles from the Iowa farm, West Virginia val- ley, or Philadelphia ethnic ghetto where they'd been born, reared, and too often ill-educated about the world beyond. In their wonderfully titled, beautifully written The First Strange Place: The Alchemy of Race and Sex in World War II Hawaii, Beth Bailey and David Farber examine the reaction of GIs and war workers to the islands. As the subtitle makes clear, they also look at the relationships between the young soldiers and the women who served as their island hostesses and helped them pass the time before leaving for the less hospitable beaches on Tarawa, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. Bailey and Farber describe a wartime Hawai'i that was, first and foremost, terribly overcrowded. A prewar population of 258,000 soon mushroomed to more than a million, some 550,000 of whom were military. This overnight population expansion could not be accommodated. -

Spring 2013 Newsletter

ma M Mala anoa Malama Manoa N E W S L E T T E R Volume 21, No. 1 / March 2013 Historic Manoa Walking Tour – Hana Hou! by Mamie Lawrence Gallagher Join Mālama Mānoa for our 9th biennial Historic Mānoa Walking Tour on Sunday, May 5th as we explore the ancient agricultural district of Pāhao of West Mānoa. Pāhao is the swath of land which extends from Pu‘uhonua towards Kapunahou above Pu‘upueo along the verdant slopes of ‘Ualaka‘a. In the early 1800s, Pāhao was one of Kamehameha's four farming areas on O‘ahu, featuring a large farmhouse from which the King could view his crops. As foreign ship traffic increased at Honolulu’s harbors, the Crown diversified, - growing potatoes for export along this rich hillside. Pāhao was stew arded by Kamehameha’s high chief Kame‘eiamoku, and in 1850 the area was divided into land grants as a result of the Kuleana Act. By1899, Pāhao had been developed into the Mānoa Heights Addition Tract and Apply for an Education Grant and Malama Your Valley opened for sale. This development, Deadline : June 1, 2013 also known as the Dorch-Schnack neighborhood and ‘Ualaka‘a Tract, features many homes listed on the - Do you know of a worthy community project? Non-profit organizations, educational Hawai‘i Register of Historic Places institutions and community groups can now apply for support from a Mālama Mānoa including the Faus/Durant resi - Education Grant. dence, architect Hart Wood’s own home, and select Mary Jane Mon We seek to fund initiatives that align with the mission of Mālama Mānoa.