Original Article Sports Skills in Sitting Volleyball Between Disabled And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boccia Bean Bags, Koosh Balls, Paper & Tape Balls, Fluff Balls

Using the Activity Cards Sports Ability is an inclusive activities program There may be some differences concerning rules, equipment that adopts a social / environmental approach and technique. However, teachers, coaches and sports leaders to inclusion. This approach concentrates on the working in a physical activity and sport setting can treat young people with a disability in a similar way to any of their other ways in which teachers, coaches and sports athletes or students. The different stages of learning and the leaders can adjust, adapt and modify the way in basic techniques of skill teaching apply equally for young people which an activity is delivered rather than focus with disabilities. A teacher, coach or sports leader can ensure on individual disabilities. their approach is inclusive by applying the TREE principle. TREE stands for: Teaching / coaching style Observing, questioning, applying and reviewing. Example: a flexible approach to communication to ensure that information is shared by all. Rules In competitive and small-sided activities. Example: allowing two bounces of the ball in a tennis activity, or more lives for some players in a tag game. Equipment Vary to provide more options. Example: using a brighter coloured ball or a sound ball to assist players with tracking. Environment Space, surface, weather conditions. Example: enabling players with different abilities to play in different sized spaces. TREE can be used as a practical tool and a mental map to help teachers, coaches and Try the suggestions provided on the back of sports leaders to adapt and modify game each card when modifying the games and situations to be more inclusive of people activities or use the TREE model to develop with wide range of abilities. -

TDSSA Expert Group Approved By: WADA Executive Committee Date: 145 November 20187 Effective Date: 1 January 20198

WADA Technical Document for Sport Specific Analysis Version Number:4.03.1 Written By: TDSSA Expert Group Approved By: WADA Executive Committee Date: 145 November 20187 Effective Date: 1 January 20198 1. Introduction As part of WADA’s move towards ensuring Anti-Doping Organizations (ADOs) implement more intelligent and effective anti-doping programs, Article 5.4.1 of the 2015 World Anti-Doping Code (WADC2015) states – “WADA, in consultation with International Federations and other Anti-Doping Organizations, will adopt a Technical Document under the International Standard for Testing and Investigations (ISTI) that establishes by means of a risk assessment which Prohibited Substances and/or Prohibited Methods are most likely to be abused in particular sports and sports disciplines.” This Technical Document for Sport Specific Analysis (TDSSA) is intended to ensure that the Prohibited Substances and/or Prohibited Methods within the scope of the TDSSA and other tools that support the detection of Prohibited Substances and/or identify the Use of Prohibited Methods such as the Athlete Biological Passport are subject to an appropriate and consistent level of analysis and adoption by all ADOs that conduct Testing in those sports/disciplines deemed at risk. Compliance with the TDSSA is mandatory under the WADC2015. The development of the TDSSA is based on a scientific approach linking physiological and non- physiological demand of Athlete performance with the potential ergogenic benefit of those Prohibited Substances and/or Prohibited Methods within the scope of the TDSSA. The TDSSA complements other anti-doping tools and programs such as the Athlete Biological Passport (ABP), intelligence gathering and investigations. -

Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games

TOKYO 2020 PARALYMPIC GAMES QUALIFICATION REGULATIONS REVISED EDITION, FEBRUARY 2021 INTERNATIONAL PARALYMPIC COMMITTEE 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games Programme Overview 3. General IPC Regulations on Eligibility 4. IPC Redistribution Policy of Vacant Qualification Slots 5. Universality Wild Cards 6. Key Dates 7. Archery 8. Athletics 9. Badminton 10. Boccia 11. Canoe 12. Cycling (Track and Road) 13. Equestrian 14. Football 5-a-side 15. Goalball 16. Judo 17. Powerlifting 18. Rowing 19. Shooting 20. Swimming 21. Table Tennis 22. Taekwondo 23. Triathlon 24. Volleyball (Sitting) 25. Wheelchair Basketball 26. Wheelchair Fencing 27. Wheelchair Rugby 28. Wheelchair Tennis 29. Glossary 30. Register of Updates INTERNATIONAL PARALYMPIC COMMITTEE 3 INTRODUCTION These Qualification Regulations (Regulations) describe in detail how athletes and teams can qualify for the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games in each of the twenty- two (22) sports on the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games Programme (Games Programme). It provides to the National Paralympic Committees (NPCs), to National Federations (NFs), to sports administrators, coaches and to the athletes themselves the conditions that allow participation in the signature event of the Paralympic Movement. These Regulations present: • an overview of the Games Programme; • the general IPC regulations on eligibility; • the specific qualification criteria for each sport (in alphabetical order); and • a glossary of the terminology used throughout the Regulations. STRUCTURE OF SPORT-SPECIFIC QUALIFICATION -

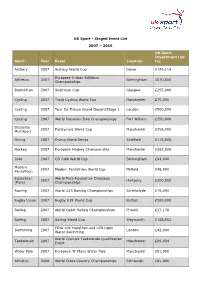

Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 Sport Year Event Location UK

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

Banquet & Event Terms

Banquet & Event Terms Banquet & Event Information Event & Party Ideas Bar & Beverage Packages Appetizers – Display & Passed Dinner Buffets Sports & Group Banquets Party Packages Youth Party Packages Additional Services & Amenities Map & Directions Frequently Asked Questions Example Contract Example Banquet Event Order Games Information House Rules Private and Semi-Private Rooms – We have several Menu - In order for us to provide you with the best service spaces throughout The Wild Game that can be set up possible, we request large parties to use one of our group private or semi-private depending on the needs of your menus. Of course, we will be happy to accommodate spe- group. If you would like to tour or reserve one of these cial vegetarian or dietary needs, as well as design a areas, please contact the Sales Coordinator on site. special menu for your specific event. Your menu must be Signed Contract - All private and semi-private events will finalized at least one week (7 days) in advance of your remain tentative and subject to cancellation until the event. complete signed contract and noted deposit are received Outdoor Functions - In the best interest of our guest, by The Wild Game. The Wild Game reserves the right to move outdoor func- Banquet Fee and Taxes – A Banquet Service Fee of 20% tions inside, if available, on the day of the function due to and all applicable local and state taxes will be added to forecasted weather. The decision made on the day of the the final bill for your event. function is final. Guarantee - The final headcount must be received a min- Room and Table Arrangements - We will do our best to imum of seven (7) days prior to the date of your function accommodate your group in the space preferred by your or event. -

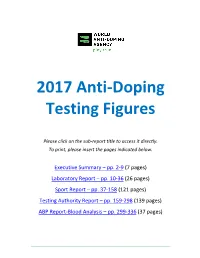

2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report

2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Please click on the sub‐report title to access it directly. To print, please insert the pages indicated below. Executive Summary – pp. 2‐9 (7 pages) Laboratory Report – pp. 10‐36 (26 pages) Sport Report – pp. 37‐158 (121 pages) Testing Authority Report – pp. 159‐298 (139 pages) ABP Report‐Blood Analysis – pp. 299‐336 (37 pages) ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Samples Analyzed and Reported by Accredited Laboratories in ADAMS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary is intended to assist stakeholders in navigating the data outlined within the 2017 Anti -Doping Testing Figures Report (2017 Report) and to highlight overall trends. The 2017 Report summarizes the results of all the samples WADA-accredited laboratories analyzed and reported into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) in 2017. This is the third set of global testing results since the revised World Anti-Doping Code (Code) came into effect in January 2015. The 2017 Report – which includes this Executive Summary and sub-reports by Laboratory , Sport, Testing Authority (TA) and Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) Blood Analysis – includes in- and out-of-competition urine samples; blood and ABP blood data; and, the resulting Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) and Atypical Findings (ATFs). REPORT HIGHLIGHTS • A analyzed: 300,565 in 2016 to 322,050 in 2017. 7.1 % increase in the overall number of samples • A de crease in the number of AAFs: 1.60% in 2016 (4,822 AAFs from 300,565 samples) to 1.43% in 2017 (4,596 AAFs from 322,050 samples). -

Press Release FIVB 2013

Gerflor, official flooring supplier to all World Volleyball Competitions 1/ Taraflex™ by Gerflor, the preferred surface of all Volleyball Competitions Gerflor has a long and proven history in Volleyball. Thanks to its partnership with the FIVB (International Volleyball Federation) since 2005, Gerflor is the exclusive supplier to all official FIVB competitions. 2/ Gerflor, on the road to London Gerflor, through IHF and FIVB agreements, supplied courts for Handball and Volleyball tournaments during the Olympic Games and courts for Sitting Volleyball during the Paralympic Games in London in 2012. Taraflex™ is the most widely specified sports surface in the world, it has been selected for ten consecutive Olympic Games from Montreal in 1976 to London in 2012 for indoor surfaces like Handball, Volleyball, Badminton and Table Tennis. Gerflor floors are the most recognized and enjoyed surface by Top Volleyball nations, players and coaches for their global sport performance. Gerflor guaranties the athletes the most oustanding and safest surface to let them express their best Talent during two weeks time. 3/ Present in over 100 countries With over 60 years of experience in the manufacture of vinyl flooring, Gerflor, manufacturer of Taraflex® Sports Flooring, has the unique position of world champion in indoor sports flooring. With over 2000 employees worldwide and significant investment in sports research and development, Gerflor always stays one step ahead of the competition. Thanks to its Taraflex® Sport brand name and product ranges, Gerflor has supplied more than 70 000 gymnasiums and sport centres (representing more than 40 million square meters) around the world. Professional and amateur athletes, sports enthusiasts and school children alike play on Taraflex® sports floors all around the world. -

Active Kids Paralympic Challenge Showcase Four Sports

FREE online resources, sports equipment and Active Kids vouchers to inspire young people to take part in Paralympic Sport. Exclusive high profile rewards for taking part: • Rio 2016 Paralympic Games trip for your school • Inclusive school playground makeover • ParalympicsGB athlete visits and signed kit for your school To register visit www.activekidsparalympicchallenge.co.uk The Active Kids Paralympic Challenge showcase four sports: Athletics Boccia Goalball At activekidsparalympicchallenge.co.uk Sitting Volleyball 16 Active Kids Paralympic Challenge resources (cards and videos) to motivate and inspire you young can access: people to participate in the challenge sports. Goalball challenge – Skittled! Goalball is a Paralympic sport played by vision impaired athletes. This challenge is based on accuracy and responding to guidance from a team-mate. What you need to do • Get into teams of 3. • The team stands or sits behind a throwing line 10 metres from the target. (10 skittles) – see graphic for set-up. Challenge format • All the players wear eyeshades and use a practice goalball or similar sound ball. • In turn, try to knock down as many Teacher resources skittles as possible in 3 goes by rolling your goalball towards the target. • The other 2 team-mates stand behind the target and call or clap to guide. • Once everyone in the team has had three attempts, add up the number of skittles knocked over to get the total team score! • Note: if all skittles are knocked down in less Travel the distance to Rio - don’t forget to than 9 rolls, re-set and finish your goes. log your activity on the Road to Rio app to stand the chance of winning great Active Kids curriculum and explains how Active Kids Paralympic Click the icon to view a video of the challenge Paralympic Challenge prizes 1 Think about that links the challenges to the PE 2 3 • Practise together to decide the best way for each player to roll the goalball and maximise the score. -

The-Almunecar-Intern

The AIS Development Award Almuñécar International School Enhancing the life skills of our young students 1 CONTENTS -3- Development Areas: Citizenship and Skills -4- Development Areas: Physical/Adventure; Research Project and Essay; Emerald, Ruby, Diamond awards -5- Who will be involved? -6- KS5: The Cambridge IPQ qualification -7- Stage of Development: Emerald – Years 7 and 8 -8- Stage of Development: Ruby – Year 9 -9- Stage of Development: Diamond – Years 10 and 11 -10- Our Learning Powers -11- to -18- Student Log Book -19- Self-Evaluation -20- Extended Ideas List -21- Extended Ideas List Continued 2 The Almuñécar International School Development Award A progressive Award The AIS Development Award: developing our commitment to education for the 21st Century so that children and young people enhance their life skills, knowledge and understanding to make a valuable contribution to their future global marketplace What are the four development areas? Each area has a list of some ideas but for even more look at the Extended Ideas List at the back of this handbook Citizenship Citizenship: students will complete various types of volunteer work. You can volunteer in school in your chosen subject areas or around school. You can also volunteer in the local community or the town where you are living. Evidence can be in the form of signatures from your supervisors. Ideas: helping with displays in classrooms or corridors. Helping departments with specific needs. Helping with our school garden. Outside of school could be helping with the upkeep of your local beach. Any ideas to help others and our communities are welcome. -

Active Schools 10 Anniversary!

ACTIVE SCHOOLS NEWSLETTER ISSUE 12 – DECEMBER 2014 ‘More Children, More Active, More Often’ ‘Tuilleadh Chlann Beothail’ Merry Christmas! Nollaig Chridheil! In this issue… Issue 12: Pupils at the Startrack December 2014 Athletics Programme 2014 Merry Christmas! Active Schools 10th Anniversary! Nollaig Chridheil! A word from the the 24 Islands compete at the LTSPA Team Leader… Commonwealth Games! Active Schools in partnership Well that was 2014! This year we are celebrating the with the Nicolson Institute have An amazing year for 10th anniversary of Active Schools designed a ‘Leadership through Scottish sport with the and over this time our main aim has Sport & Physical Activity’ success of the been to create as many elective for Secondary pupils. Commonwealth Games in Glasgow opportunities as we can for young and golf's Ryder Cup at Gleneagles people to try different sports and Page 7 in Perthshire being the highlights. activities so they go on to lead a Kerry MacPhee Both brought that wee bit closer to healthy lifestyle. This has only been us through the Queen's Baton Relay, made possible through the Local Commonwealth Games Athlete Kerry MacPhee visited South Uist's Kerry Macphee's contributions made by our small the islands to speak to pupils inclusion in the the Scottish army of volunteer coaches, teachers about her experience at the Mountain Bike squad and the visit of and senior pupils throughout the Games and her journey to the Ryder Cup to Scarista Golf Club Outer Hebrides who give up some Commonwealth Athlete. in Harris. These events showed the of their time to run sessions. -

Tribute to Athletes

TRIBUTE TO ATHLETES THE CHAMPAIGN PARK DISTRICT The Champaign Park District is a special unit of local government with its own financial and legal responsibilities. It is governed by five elected residents of Champaign who give their services to the community. The Park Board holds its regular meetings on the second Wednesday of each month at 7 pm at the Bresnan Meeting Center, 706 Kenwood Road. Residents are invited to attend and are welcome to make suggestions or comments to improve the programs or facilities offered. The Champaign Park District’s 60 parks total over 700 acres. Fourteen facilities are available for a wide variety of recreational opportunities. 2016 Commissioners Alvin S. Griggs Craig W. Hays Barbara J. Kuhl Timothy P. McMahon Jane L. Solon 2016 Dedication Ceremony Welcome ..........................................Tim McMahon ..........................................................President, Champaign Park District Board of Commissioners Introductions ...................................Jim Turpin ..........................................................WDWS Radio Words from the Architect ...............Jeffery S. Poss, AIA Remarks from the Athletes Unveiling of Plaques Paralympians .................................Joshua George .........................................................Tatyana McFadden .........................................................Amanda McGrory .........................................................Nichole Millage .........................................................Brian Siemann Mark -

Volleyball: Sitting Volleyball Sportsability

TOP Volleyball: Sitting Volleyball Sportsability Sitting Volleyball is a Paralympic sport using a smaller court and lower net. It provides an ideal activity for mixed ability groups. What you need Any suitable indoor area; ideally the court should measure 10 metres by 6 metres. Net or rope (with ribbons); ); in competition the net height is 1.15 metres (men) and 1.05 metres (women). Beach ball, light plastic or sponge ball, or standard volleyball. How to play Played by 2 teams of 6 players (or any suitable number). Most of the rules are the same as the standing game, but the main exceptions are: when playing the ball; and players are allowed to block the serve. Teams try to send the ball over the net so that it touches the ground on their opponents’ side. Rallies continue until the ball touches the ground, the ball Think about goes ‘out’, or their opponents fail to return it. A point is scored if the ball lands in the opponents’ court or Ideas that can keep the rallies going for longer; for example, they cannot return the ball. some players outside the court area who hit stray balls back into play. Normally, there is a maximum of three hits per team then the ball must cross the net. Ways of ensuring that all the players are equally involved. Volleyball: Sitting Volleyball Use the STEP model to modify this game Space Extension games ‘Go Slide’ Vary the size of the court to suit the number of players; for Sitting volleyball is not a static game; although seated, players example, if there are more players, use a bigger space.