Bassoon Playing in Perspective Character and Performance Practice from 1800 to 1850

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 5-2016 The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument Victoria A. Hargrove Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Hargrove, Victoria A., "The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 236. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/236 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT Victoria A. Hargrove COLUMBUS STATE UNIVERSITY THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO HONORS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE HONORS IN THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC SCHWOB SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE OF THE ARTS BY VICTORIA A. HARGROVE THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT By Victoria A. Hargrove A Thesis Submitted to the HONORS COLLEGE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Degree of BACHELOR OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS Thesis Advisor Date ^ It, Committee Member U/oCWV arcJc\jL uu? t Date Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz A Honors College Dean ABSTRACT The purpose of this lecture recital was to reflect upon the rapid mechanical progression of the clarinet, a fairly new instrument to the musical world and how these quick changes effected the way composers were writing music for the instrument. -

A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 4-2018 State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First- Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy Tamara Tanner University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Tanner, Tamara, "State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 115. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/115 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY by Tamara J. Tanner A Doctoral Document Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Flute Performance Under the Supervision of Professor John R. Bailey Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2018 STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY Tamara J. Tanner, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2018 Advisor: John R. Bailey During the Baroque flute revival in 1970s Europe, American modern flute instructors who were interested in studying Baroque flute traveled to Europe to work with professional instructors. -

Joana Carneiro Music Director

JOANA CARNEIRO MUSIC DIRECTOR Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 16 Berkeley Sound Composer Fellows & Full@BAMPFA 18 Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Calendar 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 37 About Music Director Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Artists & Composers 43 About Berkeley Symphony 44 Music in the Schools 47 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 49 Annual Membership Support 58 Broadcast Dates 61 Contact 62 Advertiser Index Media Sponsor Gertrude Allen • Annette Campbell-White & Ruedi Naumann-Etienne Official Wine Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Getty • Jill Grossman Sponsor Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Tricia Swift S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. October 5 & 6, 2017 3 4 October 5 & 6, 2017 Message from the Music Director Dear Friends, Happy New Season 17/18! I am delighted to be back in Berkeley after more than a year. There are three beautiful reasons for photo by Rodrigo de Souza my hiatus. I am so grateful for all the support I received from the Berkeley Symphony musicians, members of the Board and Advisory Council, the staff, and from all of you throughout this special period of my family’s life. -

2006 Heft 1 Zum Heft

MAGAZIN FÜR HOLZBLÄSER Eine Vierteljahresschrift · Einzelheft € 6,50 Heft 1/2006 Heft SSppiieellrrääuummee –– MOECK Seminare Termin: jeweils Samstags von 10.00 – 17.00 Uhr 2006 Ort: Kreismusikschule Celle, Kanonenstr. 4, 29221 Celle Carin van Heerden Peter Holtslag Der singende Telemann Der „gute“ Klang und die Blockflöte Seminar 1: 18. Februar 2006 – Widerspruch, Utopie oder Realität? Seminar 2: 6. Mai 2006 Werke von Georg Philipp Telemann für und mit Was macht einen guten Blockflötenklang aus und Blockflöte werden in diesem Workshop in Einzel- wie entsteht er? Welche Rolle spielt mein Körper? und Kammermusikstunden erarbeitet. Telemanns Muss man jeden Tag einen Marathon laufen und 2 Leitsatz Singen ist das Fundament zur Music in Liter Vitaminsaft trinken, um körperlich fit zu sein allen Dingen … Wer die Composition ergreifft, für den guten Klang? Reicht es schon aus, ein muß in seinen Sätzen singen soll die gemeinsame Instru ment der Spitzenklasse zu kaufen? Welche Arbeit an seinen Solo- und Kammermusikwerken Rol le spielen Vorstellungsvermögen und Suggesti- prägen. Eingeladen sind alle Block flötistInnen die vität? Welcher Klang passt zu welcher Musik? Wel- das Melodische bei Telemann lieben. che aufführungspraktischen Tendenzen spielen Ein Cembalo in 440 und 415 Hz sowie ein Beglei- eine Rolle für den Klang? Und: was bedeutet ter stehen bei Bedarf zur Verfügung. eigentlich „guter“ Geschmack und „guter“ Klang? In der ersten Stunde findet eine Einführung ins Folgende Werke können u. a. erarbeitet werden: Thema statt, veranschaulicht mit Klangbeispielen. – 6 Partitas (Die kleine Kammermusik für Block - Dann folgen gemeinsame Übungen und das Erar- flöte und B.c.) beiten von Stücken. – 12 Fantasien für Blockflöte solo Literaturvorschläge: – Sonaten für Altblockflöte und B.c. -

The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1966 The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions J. Wayne Johnson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, J. Wayne, "The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions" (1966). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 2804. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/2804 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IDENTIFICATION OF BAS~C PROBLEMS FOUND IN THE BASSOON PARTS OF A SELECTED GROUP OF BAND COMPOSITI ONS by J. Wayne Johnson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the r equ irements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Music Education UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan , Ut a h 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE BASSOON 3 THE I NSTRUMENT 20 Testing the bassoon 20 Removing moisture 22 Oiling 23 Suspending the bassoon 24 The reed 24 Adjusting the reed 25 Testing the r eed 28 Care of the reed 29 TONAL PROBLEMS FOUND IN BAND MUSIC 31 Range and embouchure ad j ustment 31 Embouchure · 35 Intonation 37 Breath control 38 Tonguing 40 KEY SIGNATURES AND RELATED FINGERINGS 43 INTERPRETIVE ASPECTS 50 Terms and symbols Rhythm patterns SUMMARY 55 LITERATURE CITED 56 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. -

Magnus Lindberg 1

21ST CENTURY MUSIC FEBRUARY 2010 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. ISSN 1534-3219. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $96.00 per year; subscribers elsewhere should add $48.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $12.00. Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. email: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2010 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Copy should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors are encouraged to submit via e-mail. Prospective contributors should consult The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), in addition to back issues of this journal. -

Alternative Strategies for the Refinement of Bassoon Technique Through the Concert Etudes, Op

Alternative Strategies for the Refinement of Bassoon Technique Through the Concert Etudes, Op. 26, by Ludwig Milde Item Type Electronic Dissertation; text Authors Zuniga Chanto, Fernando Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 13:14:01 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/145124 ALTERNATIVE STRATEGIES FOR THE REFINEMENT OF BASSOON TECHNIQUE THROUGH THE CONCERT ETUDES, OP. 26, BY LUDWIG MILDE by Fernando Zúñiga Chanto ______________________________ Copyright © Fernando Zúñiga Chanto 2011 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2011 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Fernando Zúñiga Chanto entitled Alternative Strategies for the Refinement of Bassoon Technique Through The Concert Etudes, Op. 26, by Ludwig Milde and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Date: 4/18/2011 William Dietz Date: 4/18/2011 Jerry Kirkbride Date: 4/18/2011 Brian Luce Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Magnus Lindberg Al Largo • Cello Concerto No

MAGNUS LINDBERG AL LARGO • CELLO CONCERTO NO. 2 • ERA ANSSI KARTTUNEN FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU MAGNUS LINDBERG (1958) 1 Al largo (2009–10) 24:53 Cello Concerto No. 2 (2013) 20:58 2 I 9:50 3 II 6:09 4 III 4:59 5 Era (2012) 20:19 ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cello (2–4) FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU, conductor 2 MAGNUS LINDBERG 3 “Though my creative personality and early works were formed from the music of Zimmermann and Xenakis, and a certain anarchy related to rock music of that period, I eventually realised that everything goes back to the foundations of Schoenberg and Stravinsky – how could music ever have taken another road? I see my music now as a synthesis of these elements, combined with what I learned from Grisey and the spectralists, and I detect from Kraft to my latest pieces the same underlying tastes and sense of drama.” – Magnus Lindberg The shift in musical thinking that Magnus Lindberg thus described in December 2012, a few weeks before the premiere of Era, was utter and profound. Lindberg’s composer profile has evolved from his early edgy modernism, “carved in stone” to use his own words, to the softer and more sonorous idiom that he has embraced recently, suggesting a spiritual kinship with late Romanticism and the great masters of the early 20th century. On the other hand, in the same comment Lindberg also mentioned features that have remained constant in his music, including his penchant for drama going back to the early defiantly modernistKraft (1985). -

The Rise and Fall of the Bass Clarinet in a the RISE and FALL of the BASS CLARINET in A

Keith Bowen - The rise and fall of the bass clarinet in A THE RISE AND FALL OF THE BASS CLARINET IN A Keith Bowen The bass clarinet in A was introduced by Wagner in Lohengrin in 1848. Unlike the bass instruments in C and Bb, it is not known to have a history in wind bands. Its appearance was not, so far as is known, accompanied by any negotiations with makers. Over the next century, it was called for by over twenty other composers in over sixty works. The last works to use the bass in A are, I believe, Strauss’ Sonatine für Blaser, 1942, and Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie (1948, revised 1990) and Gunther Schuller’s Duo Sonata (1949) for clarinet and bass clarinet. The instrument has all but disappeared from orchestral use and there are very few left in the world. It is now often called obsolete, despite the historically-informed performance movement over the last half century which emphasizes, inter alia, performance on the instruments originally specified by the composer. And the instrument has been largely neglected by scholars. Leeson1 drew attention to the one-time popularity and current neglect of the instrument, in an article that inspired the current study, and Joppig2 has disussed the use of the various tonalities of clarinet, including the bass in A, by Gustav Mahler. He pointed out that the use of both A and Bb clarinets in both soprano and bass registers was absolutely normal in Mahler’s time, citing Heinrich Schenker writing as Artur Niloff in 19083. Otherwise it has been as neglected in the literature as it is in the orchestra. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

What Is the Sound of Modern Music?

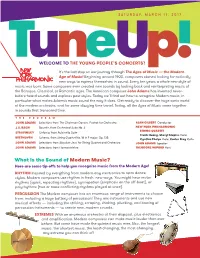

SATURDAY, MARCH 11, 2017 Mozart’s “Classical” European tour? A TuWELCOMEn TO THE YOUNGe PEOPLE’SU CONCERTS!TM p! It’s the last stop on our journey through The Ages of Music — the Modern Age of Music! Beginning around 1900, composers started looking for radically new ways to express themselves in sound. Every ten years a whole new style of music was born. Some composers even created new sounds by looking back and reinterpreting music of the Baroque, Classical, or Romantic ages. The American composer John Adams has invented never- before-heard sounds and explores past styles. Today we’ll find out how to recognize Modern music, in particular what makes Adams’s music sound the way it does. Get ready to discover the huge sonic world of the modern orchestra, and for some dizzying time travel. Today, all the Ages of Music come together in sounds that transcend time. THE PROGRAM JOHN ADAMS Selections from The Chairman Dances, Foxtrot for Orchestra ALAN GILBERT Conductor J.S. BACH Bourrée, from Orchestral Suite No. 3 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC STRING QUARTET STRAVINSKY Sinfonia, from Pulcinella Suite Frank Huang, Sheryl Staples Violin BEETHOVEN Scherzo, from String Quartet No. 16 in F major, Op. 135 Cynthia Phelps Viola; Carter Brey Cello JOHN ADAMS Selections from Absolute Jest, for String Quartet and Orchestra JOHN ADAMS Speaker JOHN ADAMS Selections from Harmonielehre THEODORE WIPRUD Host What Is the Sound of Modern Music? Here are some tip-offs to help you recognize music from the Modern Age! RHYTHM Inspired by everything from modern-day electronics to retro dance styles, Modern composers use rhythm in fresh, new ways. -

30N2 Programs

Sonata for Tuba and Piano Verne Reynolds FACULTY/PROFESSIONAL PERFORMANCES The Morning Song Roger Kellaway Edward R. Bahr, euphonium Salve Venere, Salve Marte John Stevens Concerto No. 1 for Hom, Op. 11 Richard Strauss Delta Sate University, Cleveland, MS 10/03/02 Csdrdds Vittorio Monti / arr. Ronald Davis Suite No. IV for Violoncello S. 1010 J.S. Bach Vocalises Giovanni Marco Bordogni Michael Fischer, tuba "Andante maestosoAndante mosso" Boise State University, Boise, ID WllljOl "Allegro" Central Missouri State University, Warrensburg, MO 11/1/02 (Johannes Rochut: Melodius Etudes No. 79, 24) Pittsburg State University, Pittsburg, KS 11/4/02 Concertino No. I in Bflat, op. 7 .Julius Klengel/an:. Leonard Falcone Romance Op. 36 Camille SaintSaens/arr. Michael Fischer GranA Concerto Friedebald Grafe Beelzebub Andrea V. Catozzi/arr. Julius S. Seredy Reverie et Balade Rene Mignion Three Romantic Pieces arr. Michael Fischer Danza Espagnola David Uber Du Ring an meinem Finger, Robert Schumann, Op. 42, No. 4 Velvet Brown, tuba Felteinsamkeit, Johannes Brahms Standchen, Franz Schubert *Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH 10/23/02 **Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 10/24/02 Gypsy Songs .Johannes Brahms/arr. by Michael Fischer Sonata Bruce Broughton The Liberation of Sisyphus John Stevens Chant du Menestrel, op. 71 Alexander Glazunov/arr. V. Brown Adam Frey, euphonium Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen Gustav Mahler/arr. D. Perantoni Mercer University, Macon, GAl0/01/02 *Te Dago Mi for tuba, euphonium and piano (U.S. premiere) Velvet Brown with Benjamin Pierce, euphonium Sormta in F Major.. Benedetto Marcello Blue Lake for Solo Euphonium **Mus!c for Two Big Instruments Alex Shapiro Fantasies David Gillingham Sonata for tuba and piano Juraj Filas Peace John Golland Rumanian Dance No.