Adivasi-Kurumba Corpses Perform Their Own Burial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu Connie Smith Tamil Nadu Overview

Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu Connie Smith Tamil Nadu Overview Tamil Nadu is bordered by Pondicherry, Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. Sri Lanka, which has a significant Tamil minority, lies off the southeast coast. Tamil Nadu, with its traceable history of continuous human habitation since pre-historic times has cultural traditions amongst the oldest in the world. Colonised by the East India Company, Tamil Nadu was eventually incorporated into the Madras Presidency. After the independence of India, the state of Tamil Nadu was created in 1969 based on linguistic boundaries. The politics of Tamil Nadu has been dominated by DMK and AIADMK, which are the products of the Dravidian movement that demanded concessions for the 'Dravidian' population of Tamil Nadu. Lying on a low plain along the southeastern coast of the Indian peninsula, Tamil Nadu is bounded by the Eastern Ghats in the north and Nilgiri, Anai Malai hills and Palakkad (Palghat Gap) on the west. The state has large fertile areas along the Coromandel coast, the Palk strait, and the Gulf of Mannar. The fertile plains of Tamil Nadu are fed by rivers such as Kaveri, Palar and Vaigai and by the northeast monsoon. Traditionally an agricultural state, Tamil Nadu is a leading producer of agricultural products. Tribal Population As per 2001 census, out of the total state population of 62,405,679, the population of Scheduled Castes is 11,857,504 and that of Scheduled Tribes is 651,321. This constitutes 19% and 1.04% of the total population respectively.1 Further, the literacy level of the Adi Dravidar is only 63.19% and that of Tribal is 41.53%. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kannur District from 19.04.2020To25.04.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kannur district from 19.04.2020to25.04.2020 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Name of the Age & Address of Cr. No & Police Sl. No. father of which Time of Officer, at which Accused Sex Accused Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 560/2020 U/s 269,271,188 IPC & Sec ZHATTIYAL 118(e) of KP Balakrishnan NOTICE HOUSE, Chirakkal 25-04- Act &4(2)(f) VALAPATTA 19, Si of Police SERVED - J 1 Risan k RASAQUE CHIRAkkal Amsom 2020 at r/w Sec 5 of NAM Male Valapattanam F C M - II, amsom,kollarathin Puthiyatheru 12:45 Hrs Kerala (KANNUR) P S KANNUR gal Epidermis Decease Audinance 2020 267/2020 U/s KRISNA KRIPA NOTICE NEW MAHE 25-04- 270,188 IPC & RATHEESH J RAJATH NALAKATH 23, HOUSE,Nr. New Mahe SERVED - J 2 AMSOM MAHE 2020 at 118(e) of KP .S, SI OF VEERAMANI, VEERAMANI Male HEALTH CENTER, (KANNUR) F C M, PALAM 19:45 Hrs Act & 5 r/w of POLICE, PUNNOL THALASSERY KEDO 163/2020 U/s U/S 188, 269 Ipc, 118(e) of Kunnath house, kp act & sec 5 NOTICE 25-04- Abdhul 28, aAyyappankavu, r/w 4 of ARALAM SERVED - J 3 Abdulla k Aralam town 2020 at Sudheer k Rashhed Male Muzhakunnu kerala (KANNUR) F C M, 19:25 Hrs Amsom epidemic MATTANNUR diseases ordinance 2020 149/2020 U/s 188,269 NOTICE Pathiriyad 25-04- 19, Raji Nivas,Pinarayi IPC,118(e) of Pinarayi Vinod Kumar.P SERVED - A 4 Sajid.K Basheer amsom, 2020 at Male amsom Pinarayi KP Act & 4(2) (KANNUR) C ,SI of Police C J M, Mambaram 18:40 Hrs (f) r/w 5 of THALASSERY KEDO 2020 317/2020 U/s 188, 269 IPC & 118(e) of KP Act & Sec. -

Socio-Economic Characteristics of Tribal Communities That Call Themselves Hindu

Socio-economic Characteristics of Tribal Communities That Call Themselves Hindu Vinay Kumar Srivastava Religious and Development Research Programme Working Paper Series Indian Institute of Dalit Studies New Delhi 2010 Foreword Development has for long been viewed as an attractive and inevitable way forward by most countries of the Third World. As it was initially theorised, development and modernisation were multifaceted processes that were to help the “underdeveloped” economies to take-off and eventually become like “developed” nations of the West. Processes like industrialisation, urbanisation and secularisation were to inevitably go together if economic growth had to happen and the “traditional” societies to get out of their communitarian consciousness, which presumably helped in sustaining the vicious circles of poverty and deprivation. Tradition and traditional belief systems, emanating from past history or religious ideologies, were invariably “irrational” and thus needed to be changed or privatised. Developed democratic regimes were founded on the idea of a rational individual citizen and a secular public sphere. Such evolutionist theories of social change have slowly lost their appeal. It is now widely recognised that religion and cultural traditions do not simply disappear from public life. They are also not merely sources of conservation and stability. At times they could also become forces of disruption and change. The symbolic resources of religion, for example, are available not only to those in power, but also to the weak, who sometimes deploy them in their struggles for a secure and dignified life, which in turn could subvert the traditional or establish structures of authority. Communitarian identities could be a source of security and sustenance for individuals. -

The Dravidian Languages

THE DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGES BHADRIRAJU KRISHNAMURTI The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Bhadriraju Krishnamurti 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Times New Roman 9/13 pt System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0521 77111 0hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page xi List of tables xii Preface xv Acknowledgements xviii Note on transliteration and symbols xx List of abbreviations xxiii 1 Introduction 1.1 The name Dravidian 1 1.2 Dravidians: prehistory and culture 2 1.3 The Dravidian languages as a family 16 1.4 Names of languages, geographical distribution and demographic details 19 1.5 Typological features of the Dravidian languages 27 1.6 Dravidian studies, past and present 30 1.7 Dravidian and Indo-Aryan 35 1.8 Affinity between Dravidian and languages outside India 43 2 Phonology: descriptive 2.1 Introduction 48 2.2 Vowels 49 2.3 Consonants 52 2.4 Suprasegmental features 58 2.5 Sandhi or morphophonemics 60 Appendix. Phonemic inventories of individual languages 61 3 The writing systems of the major literary languages 3.1 Origins 78 3.2 Telugu–Kannada. -

Origin Al Article

International Journal of History and Research (IJHR) ISSN (P): 2249–6963; ISSN (E): 2249–8079 Vol. 11, Issue 2, Dec 2021, 9–12 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. SOCIO-CULTURAL ASPECTS OF KURUMBAS IN THE NILGIRI DISTRICT – A STUDY D. KASTURI1 & DR. KANAGAMBAL2 1Ph.D. Scholar, Dept. of History, Govt. Arts College, Udhagamandalam, The Nilgiris. Tamil Nadu, India. 2 Asst. Professor and Head, Dept. of History, Govt. Arts College, Udhagamandalam, The Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India. ABSTRACT Kurumbas are a recognised scheduled tribe in Kerala and Tamil Nadu. They are one of the earliest known inhabitants of the Western Ghats, collecting and harvesting forest produce, primarily wild honey and wax. They have traditionally subsisted as hunters and gatherers. They live in jungles on the plateau's steep edge, where they conduct shifting agriculture as well as feeding and catching tiny birds and animals. Historically, the Kurumbas and other tribes have enjoyed a cooperative relationship that includes the trading of commodities and services. Members of this group are short, have a dark complexion and prominent brows of their community practise Hinduism and speak a language that is Original Article a hybrid of Dravidian dialects. KEYWORDS: Intricate Interpretation and Scrutiny of Bygone Occurrences Received: Jun 01, 2021; Accepted: Jun 21, 2021; Published: Jun 29, 2021; Paper Id.: IJHRDEC20212 INTRODUCTION The history of people who settled in the Nilgiris hills has been documented for ages. The Blue Mountains were most likely named for the abundant blue strobilanthes flowers that bloomed in the area's foggy atmosphere. The indigenous tribal peoples of the Toda, Kota, Kurumbas, and Irula have long lived in this area. -

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

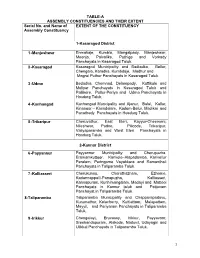

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Details of Crushers in Kannur District As on the Date of Completion Of

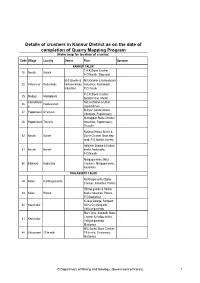

Details of crushers in Kannur District as on the date of completion of Quarry Mapping Program (Refer map for location of crusher) Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator KANNUR TALUK T.A.K.Stone Crusher , 16 Narath Narath P.O.Narath, Step road M/S Granite & M/S Granite & Hollowbricks 20 Valiyannur Kadankode Holloaw bricks, Industries, Kadankode , industries P.O.Varam P.C.K.Stone Crusher, 25 Madayi Madaippara Balakrishnan, Madai Cherukkunn Natural Stone Crusher, 26 Pookavanam u Jayakrishnan Muliyan Constructions, 27 Pappinisseri Chunkam Chunkam, Pappinissery Muthappan Stone Crusher 28 Pappinisseri Thuruthi Industries, Pappinissery, Thuruthi National Hollow Bricks & 52 Narath Narath Stone Crusher, Near step road, P.O.Narath, Kannur Abhilash Granite & Hollow 53 Narath Narath bricks, Neduvathu, P.O.Narath Maligaparambu Metal 60 Edakkad Kadachira Crushers, Maligaparambu, Kadachira THALASSERY TALUK Karithurparambu Stone 38 Kolari Karithurparambu Crusher, Industries, Porora Hill top granite & Hollow 39 Kolari Porora bricks industries, Porora, P.O.Mattannur K.Jose George, Sampath 40 Keezhallur Stone Crushing unit, Velliyamparambu Mary Jose, Sampath Stone Crusher & Hollow bricks, 41 Keezhallur Velliyamparambu, Mattannur M/S Santhi Stone Crusher, 44 Chavesseri 19 th mile 19 th mile, Chavassery, Mattannur © Department of Mining and Geology, Government of Kerala. 1 Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator M/S Conical Hollow bricks 45 Chavesseri Parambil industries, Chavassery, Mattannur Jaya Metals, 46 Keezhur Uliyil Choothuvepumpara K.P.Sathar, Blue Diamond Vellayamparamb 47 Keezhallur Granite Industries, u Velliyamparambu M/S Classic Stone Crusher 48 Keezhallur Vellay & Hollow Bricks Industries, Vellayamparambu C.Laxmanan, Uthara Stone 49 Koodali Vellaparambu Crusher, Vellaparambu Fivestar Stone Crusher & Hollow Bricks, 50 Keezhur Keezhurkunnu Keezhurkunnu, Keezhur P.O. -

A Sociolinguistic Survey of Nilgiri Irula

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2018-010 A Sociolinguistic Survey of Nilgiri Irula Researched and compiled by Sylvia Ernest, Clare O’Leary, and Juliana Kelsall A Sociolinguistic Survey of Nilgiri Irula Researched and compiled by Sylvia Ernest, Clare O’Leary, and Juliana Kelsall SIL International® 2018 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2018-010, October 2018 © 2018 SIL International® All rights reserved Data and materials collected by researchers in an era before documentation of permission was standardized may be included in this publication. SIL makes diligent efforts to identify and acknowledge sources and to obtain appropriate permissions wherever possible, acting in good faith and on the best information available at the time of publication Abstract The purpose of this sociolinguistic survey of three Nilgiri Irula [iru] speech varieties (Mele Nadu, Vette Kada, and Northern) was to provide an initial assessment of the viability of vernacular literature development. The fieldwork was conducted during the latter half of 1992 and the early part of 1993. The original report was written as an unpublished paper that was completed in mid-1993. The research instruments used for this survey were wordlists, Recorded Text Testing (RTT), sociolinguistic questionaires, and a Tamil Sentence Repetition Test (SRT) that was developed during the course of the fieldwork. SRT results indicated that more than half of Irula speakers, especially those living in more remote villages, would probably have difficulty using complex written materials in Tamil. Questionaire results indicated that Irula is a vital language and is being maintained consistently within the Irula community. RTT results, along with dialect attitudes and reported contact patterns, tentatively pointed to Mele Nadu Irula as the preferred form for language development and literacy materials. -

District Survey Report of Minor Minerals (Except River Sand)

GOVERNMENT OF KERALA DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT OF MINOR MINERALS (EXCEPT RIVER SAND) Prepared as per Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification, 2006 issued under Environment (Protection) Act 1986 by DEPARTMENT OF MINING AND GEOLOGY www.dmg.kerala.gov.in November, 2016 Thiruvananthapuram Table of Contents Page no. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 2 Administration ........................................................................................................................... 3 3 Drainage and Irrigation .............................................................................................................. 3 4 Rainfall and climate.................................................................................................................... 4 5 Other meteorological parameters ............................................................................................. 6 5.1 Temperature .......................................................................................................................... 6 5.2 Relative Humidity ................................................................................................................... 6 5.3 Evaporation ............................................................................................................................ 6 5.4 Sunshine Hours ..................................................................................................................... -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kannur District from 07.02.2021To13.02.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Kannur district from 07.02.2021to13.02.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kaippanplakkal Nariyanpara 13-02-2021 54/2021 U/s 27, ALACODE BAILED BY 1 Midhun K M Mohanan House,mavumthattu Alakode at 19:50 118(a) of KP Ranjith M K Male (KANNUR) POLICE ,Udayagiri Amsom Amsom Hrs Act 13-02-2021 49/2021 U/s Vinod.T, S I of Abdul 18, Ponnan house, S. S Dharmadam Bailed by 2 Nisthar Illikkunnu at 22:35 118(a) of KP Police, Basith Male Road, Thalassery (KANNUR) Police Hrs Act Dharmadam PS KEEZHUR THEKODAN HOUSE AMSOM 13-02-2021 54, PAYA M AMSOM 44/2021 U/s Iritty Bailed by 3 RAJAN THAKARAJ SOORYA BAR at 22:25 MOHANAN Male PERUPARAMBA 15 of KG Act (KANNUR) Police NEAR Hrs IRITTY PUHZAKARA KEEZHUR PULIKKAL HOUSE AMSOM 13-02-2021 29, PAYAM AMSOM 44/2021 U/s Iritty MOHANAN SI Bailed by 4 SANOJ George SOORYA BAR at 22:45 Male PERURUMPARAMBA 15 of KG Act (KANNUR) OF POLICE Police NEAR Hrs IRITTY PUHZAKARA KEEZHUR KAKKADATHU AMSOM 13-02-2021 39, HOUSE ARLAM 44/2021 U/s Iritty MOHANAN SI Bailed by 5 SANESH APPU SOORYA BAR at 22:25 Male AMSOM 15 of KG Act (KANNUR) OF POLICE Police NEAR Hrs KEEZHPALLY IRITTY PUHZAKARA Keerthi house, 13-02-2021 63/2021 U/s Subhash 45, Kathirur Abhilash,SI of BAILED BY 6 Chathukutty Kathirur amsam, Ponniam Palam at 20:05 118(a) of KP Chandran Male (KANNUR) Police POLICE Pullyodi Hrs Act 48/2021 U/s K. -

Covid-19 Outbreak Control and Prevention State Cell Health & Family

COVID-19 OUTBREAK CONTROL AND PREVENTION STATE CELL HEALTH & FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT GOVT. OF KERALA www.health.kerala.gov.in www.dhs.kerala.gov.in [email protected] Date: 20/08/2020 Time: 02:00 PM The daily COVID-19 bulletin of the Department of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Kerala summarizes the COVID-19 situation in Kerala. The details of hotspots identified are provided in Annexure-1 for quick reference. The bulletin also contains links to various important documents, guidelines, and websites for references. OUR HEALTH OUR RESPONSIBILITY • Maintain a distance of at least two metres with all people all the time. • Always wear clean face mask appropriately everywhere all the time • Perform hand hygiene after touching objects and surfaces all the time. • Perform hand hygiene before and after touching your face. • Observe cough and sneeze hygiene always • Stay Home; avoid direct social interaction and avoid travel • Protect the elderly and the vulnerable- Observe reverse quarantine • Do not neglect even mild symptoms; seek health care “OUR HEALTH OUR RESPONSIBILITY” Page 1 of 22 PART- 1 SUMMARY OF COVID CASES AND DEATH Table 1. Summary of COVID-19 cases till 19/08/2020 New Persons New persons added to New persons Positive Recovered added to Home, in Hospital Deaths cases patients Quarantine/ Institution Isolation Isolation quarantine 50231 32611 169687 155928 13759 182 Table 2. Summary of new COVID-19 cases (last 24 hours) New Persons New persons added to New persons Positive Recovered added to Home, in Hospital Deaths cases patients Quarantine/ Institution Isolation Isolation quarantine 1968 1217 11447 9249 2198 9 Table 3. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kannur District from 12.04.2020To18.04.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kannur district from 12.04.2020to18.04.2020 Name of Name of Name of Place at Date & Arresting the Court Name of the the father Age & Address of Cr. No & Police Sl. No. which Time of Officer, at which Accused of Sex Accused Sec of Law Station Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 286/2020 U/s NOTICE Sakeena 188,269,IPC 18-04- Ajith Kumar SERVED - J 35, Manzil Mukkile Anjerakandy &sec 118(e) Of Kuthuparamb 1 Sajeer M Assainar 2020 at KP, SI of F C M, Male peedika Jn KP Act&sec a (KANNUR) 19:35 Hrs Police KUTHUPARA Vellachal Bavod &sec. 4(2)(a)5 MBA KEDO 202 314/2020 U/s 269, 188 IPC & 118(e) of KP E K HOUSE, Edakkad Act & Sec. 5 NOTICE 18-04- 28, HUSSAN amsom r/w 4 of Edakkad SERVED - A 2 ASHRAF E K ASEES E K 2020 at Sheeju T K Male MUKKU, PO Hussan Kerala (KANNUR) C J M, 20:25 Hrs EDAKKAD Mukku Epidemic THALASSERY Diseases Ordinance 2020 313/2020 U/s 269, 188 IPC & 118(e) of KP Najamas, Edakkad Act & Sec. 5 NOTICE 18-04- 30, Hussan amsom r/w 4 of Edakkad SERVED - A 3 Shameel A M Mayan A P 2020 at Sheeju T K Male Mukku, Hussan Kerala (KANNUR) C J M, 20:10 Hrs Edakkad PO Mukku Epidemic THALASSERY Diseases Ordinance 2020 130/2020 U/s U/S 188 ,269 IPC and 118(e) Rubeena of KP Act and Umeshan.