Downloaded 2021-09-30T19:47:42Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae Simon Barron B

CURRICULUM VITAE SIMON BARRON B. Sc. (Hons), MCIEEM, CEnv EDUCATION 1991 – 1994 University of Plymouth Grade 2:1, B.Sc. (Hons.) in Geography. Modules studied include Biological Conservation, Environmental Impact Assessment, Vegetation Patterns and Processes and Surveying and Cartography. CAREER HISTORY Director of Ecology, BEC Consultants. July 2004 – Present Project manager and senior ecologist for many projects carried out at national, regional and site specific scales. These include the Pilot Survey and Phases 1-4 of the National Survey of Upland Habitats (2008 – 2014) and the National Survey of Irish Sea Cliffs (2011). I have also been project manager and lead ecologist for a number of rare plant translocation and monitoring projects. I have completed a number of Appropriate Assessments (AA), Ecological Impact Assessments (EcIA), Alien Invasive Species Surveys (AIS) rare plant surveys and habitat restoration projects. I have worked on a number of Local Biodiversity Action Plans and am a proficient habitat surveyor and botanist and have excellent report writing skills. As Director of Ecology I also have responsibility for company development, staff management and recruitment, and sit on the Senior Management Team, Project Management Team and Health and Safety Committee. A selection of projects I have worked on recently with BEC is listed below: Local Biodiversity Action Plans (2020): Project Ecologist. Conducting a review of the existing biodiversity interest of three areas: Omeath, Co. Louth, Navan Co. Meath, Griffeen River and Lucan Co. Dublin. Completing habitat surveys and preparing recommendations which could be implemented by local community groups to improve biodiversity and enhance engagement of local communities with biodiversity. -

HERITAGE PLAN 2016-2020 PHOTO: Eoghan Lynch BANKS of a CANAL by Seamus Heaney

HERITAGE PLAN 2016-2020 PHOTO: Eoghan Lynch BANKS OF A CANAL by Seamus Heaney Say ‘canal’ and there’s that final vowel Towing silence with it, slowing time To a walking pace, a path, a whitewashed gleam Of dwellings at the skyline. World stands still. The stunted concrete mocks the classical. Water says, ‘My place here is in dream, In quiet good standing. Like a sleeping stream, Come rain or sullen shine I’m peaceable.’ Stretched to the horizon, placid ploughland, The sky not truly bright or overcast: I know that clay, the damp and dirt of it, The coolth along the bank, the grassy zest Of verges, the path not narrow but still straight Where soul could mind itself or stray beyond. Poem Above © Copyright Reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. Waterways Ireland would like to acknowledge and thank all the participants in the Heritage Plan Art and Photographic competition. The front cover of this Heritage Plan is comprised solely of entrants to this competition with many of the other entries used throughout the document. HERITAGEPLAN 2016-2020 HERITAGEPLAN 2016-2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................4 Waterways Ireland ......................................................................................................................................6 Who are Waterways Ireland?................................................................................................................6 What -

NRA M50 Multi-Point Tolling

National Roads Authority Supplementary Report M50 Multi-Point Tolling Preliminary Implementation Plan Date: 20 May 2011 WORKING DRAFT (Issued) Information Note: This report was prepared for the Department of Transport by the National Roads Authority with the assistance of Roughan & O’Donovan AECOM Alliance and Goodbody Economic Consultants. National Roads Authority M50 Multi-Point Tolling Preliminary Implementation Plan Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction 2 2. Project Description (Scope & Objectives) 4 3. Legislative Framework 6 4. Proposed Tolling & Operational Regime 12 5. Delivery / Procurement Approach 24 Appendix A – Map of Proposed Tolling Locations Appendix B – Report on Network Tolling Options, 1 November 2010 Roughan & O'Donovan – Goodbody Economic Aecom Alliance Consultants Grand Canal House Ballsbridge Park Upper Grand Canal Street Ballsbridge Dublin 4 Dublin 4 www.aecom.com www.goodbody.ie/consultants Page 1 of 29 National Roads Authority M50 Multi-Point Tolling Preliminary Implementation Plan 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Background 1.1.1 In November 2010, the National Roads Authority submitted a feasibility report to the Department of Transport setting out a number of options for generating additional revenue from road tolling to support future transport investment and maintenance. This feasibility report (appended to this document for ease of reference) reviewed the following options: ▪ Work-package A: Raising Tolls at Existing Facilities; ▪ Work-package B: Introducing new tolls on existing roads comprising: ▪ Work-package B1: M50 Multi-Point Tolling (M50 MPT); ▪ Work-package B2: Tolling Charges on Dublin Radial Routes; ▪ Work-package B3: Tolling Charges on Jack Lynch Tunnel, Cork; ▪ Work-package B4: Tolling Charges on N18, N9 and N11; ▪ Work-package C: Introducing new toll charges on new roads. -

Leitrim Council

Development Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 County / City Council GIS X GIS Y Acorn Wood Drumshanbo Road Leitrim Village Leitrim Acres Cove Carrick Road (Drumhalwy TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Aigean Croith Duncarbry Tullaghan Leitrim Allenbrook R208 Drumshanbo Leitrim 597522 810404 Bothar Tighernan Attirory Carrick-on- Shannon Leitrim Bramble Hill Grovehill Mohill Leitrim Carraig Ard Lisnagat Carrick-on- Shannon Leitrim 593955 800956 Carraig Breac Carrick Road (Moneynure TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Canal View Leitrim Village Leitrim 595793 804983 Cluain Oir Leitrim TD Leitrim Village Leitrim Cnoc An Iuir Carrick Road (Moneynure TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Cois Locha Calloughs Carrigallen Leitrim Cnoc Na Ri Mullaghnameely Fenagh Leitrim Corr A Bhile R280 Manorhamilton Road Killargue Leitrim 586279 831376 Corr Bui Ballinamore Road Aughnasheelin Leitrim Crannog Keshcarrigan TD Keshcarrigan Leitrim Cul Na Sraide Dromod Beg TD Dromod Leitrim Dun Carraig Ceibh Tullylannan TD Leitrim Village Leitrim Dun Na Bo Willowfield Road Ballinamore Leitrim Gleann Dara Tully Ballinamore Leitrim Glen Eoin N16 Enniskillen Road Manorhamilton Leitrim 589021 839300 Holland Drive Skreeny Manorhamilton Leitrim Lough Melvin Forest Park Kinlough TD Kinlough Leitrim Mac Oisin Place Dromod Beg TD Dromod Leitrim Mill View Park Mullyaster Newtowngore Leitrim Mountain View Drumshanbo Leitrim Oak Meadows Drumsna TD Drumsna Leitrim Oakfield Manor R280 Kinlough Leitrim 581272 855894 Plan Ref P00/631 Main Street Ballinamore Leitrim 612925 811602 Plan Ref P00/678 Derryhallagh TD Drumshanbo -

Drumcree 4 Standoff: Nationalists Will

UIMH 135 JULY — IUIL 1998 50p (USA $1) Drumcree 4 standoff: Nationalists will AS we went to press the Drumcree standoff was climbdown by the British in its fifth day and the Orange Order and loyalists government. were steadily increasing their campaign of The co-ordinated and intimidation and pressure against the nationalist synchronised attack on ten Catholic churches on the night residents in Portadown and throughout the Six of July 1-2 shows that there is Counties. a guiding hand behind the For the fourth year the brought to a standstill in four loyalist protests. Mo Mowlam British government looks set to days and the Major government is fooling nobody when she acts back down in the face of Orange caved in. the innocent and seeks threats as the Tories did in 1995, The ease with which "evidence" of any loyalist death 1996 and Tony Blair and Mo Orangemen are allowed travel squad involvement. Mowlam did (even quicker) in into Drurncree from all over the Six Counties shows the The role of the 1997. constitutional nationalist complicity of the British army Once again the parties sitting in Stormont is consequences of British and RUC in the standoff. worth examining. The SDLP capitulation to Orange thuggery Similarly the Orangemen sought to convince the will have to be paid by the can man roadblocks, intimidate Garvaghy residents to allow a nationalist communities. They motorists and prevent 'token' march through their will be beaten up by British nationalists going to work or to area. This was the 1995 Crown Forces outside their the shops without interference "compromise" which resulted own homes if they protest from British policemen for in Ian Paisley and David against the forcing of Orange several hours. -

Report on the Accounts of the Public Services 2012

Comptroller and Auditor General Report on the Accounts of the Public Services 2012 September 2013 2 Report on the Accounts of the Public Services 2012 © Government Copyright Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General Report on the Accounts of the Public Services 2012 I am required under Section 3 of the Comptroller and Auditor General (Amendment) Act 1993 to report to Dáil Éireann on my audit of the appropriation accounts of departments and offices and the account of the receipt of revenue of the State. I have certified each appropriation account for the year ended 31 December 2012 and am submitting those accounts, together with my audit certificates, to Dáil Éireann. I hereby present my report on matters arising out of my audits of the accounts of the public services for 2012 to Dáil Éireann in accordance with Section 3 (11) of the Comptroller and Auditor General (Amendment) Act 1993. I am required under other statutes to report on certain matters along with my report on the appropriation accounts. The report is set out in four parts. Part 1 deals with matters relating to the Central Fund of the Exchequer and government debt. Part 2 outlines certain matters related to voted expenditure in 2012. Part 3 deals with matters arising out of the audit of the Revenue account and the examination of Revenue systems. Part 4 comprises my statutory report on the audits of the accounts of the National Treasury Management Agency and a report on the Clinical Indemnity Scheme. This report was prepared on the basis of audited information, where available, and other information, documentation and explanations obtained from the relevant Government departments and agencies. -

Page 1 of 3 Catherine Murphy, TD Dáil Éireann Kildare Street Dublin 2

Catherine Murphy, T.D. Dáil Éireann Kildare Street Dublin 2 - D02 A272 9th July 2020 Dear Deputy I am writing to you concerning the matter you raised in Parliamentary Question No. 935 on 3 June last to the Minister for Transport, Tourism and Sport, which has been referred to the National Transport Authority (NTA) for reply. Royal Canal Greenway The Royal Canal Greenway is a key element of the Dublin - Galway National Cycle Route, running through Dublin City, Fingal County and Kildare County Council areas. Within the Greater Dublin Area, the scheme is being developed by those local authorities in collaboration with, and funded by, the NTA. The alignment of the scheme parallels the Canal, swapping between the northern and southern sides so as to minimise impacts to the receiving environment. Construction of Phase 2 (between Sherriff Street Upper and North Strand Road - a distance of 0.72 km) began last year and is due for completion shortly. This section includes a new bridge, ramps, underpass and linear park. Phase 3 (between North Strand Road and Phibsborough Road) is currently at detailed design and will progress to construction in 2021. Phase 4 (between Ashtown and Cross Gunns Bridge) is also at detailed design and sections will progress to construction later this year. Consideration is being given to options for the development of the section between Castleknock and the border of Fingal / Kildare and the outcome of that work is expected to progress to planning later this year. Page 1 of 3 The remaining section, which extends from the Fingal / Kildare boundary to Maynooth has Part 8 planning approval. -

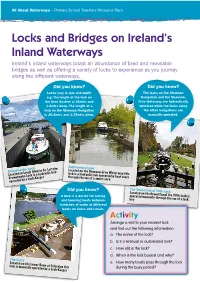

Locks and Bridges on Ireland's Inland Waterways an Abundance of Fixed

ack eachers Resource P ways – Primary School T All About Water Locks and Bridges on Ireland’s Inland Waterways Ireland’s inland waterways boast an abundance of fixed and moveable bridges as well as offering a variety of locks to experience as you journey along the different waterways. Did you know? Did you know? The locks on the Shannon Navigation and the Shannon- Locks vary in size and depth Erne Waterway are hydraulically e.g. the length of the lock on operated while the locks along the Erne System is 36mtrs and the other navigations are 1.2mtrs deep. The length of a manually operated. lock on the Shannon Navigation is 29.2mtrs and 1.35mtrs deep. Ballinamore Lock im aterway this Lock . Leitr Located on the Shannon-Erne W n in Co ck raulic lock operated by boat users gh Alle ulic lo lock is a hyd Drumshanbon Lou ydra ugh the use of a smart card cated o ock is a h thro Lo anbo L eeper rumsh ock-K D ed by a L operat The Grand Canal 30th Lock Did you know? Located on the Grand Canal the 30th Lock is operated manually through the use of a lock A lock is a device for raising key and lowering boats between stretches of water of different levels on rivers and canals. Activity Arrange a visit to your nearest lock and find out the following information: a. The name of the lock? b. Is it a manual or automated lock? c. How old is the lock? d. -

GROUP / ORGANISATION Name of TOWN/VILLAGE AREA AMOUNT

GROUP / ORGANISATION AMOUNT AWARDED by LCDC Name of TOWN/VILLAGE AREA Annaduff ICA Annaduff €728 Aughameeney Residents Association Carrick on Shannon €728 Bornacoola Game & Conservation Club Bornacoola €728 Breffni Family Resource Centre Carrick on Shannon €728 Carrick-on Shannon & District Historical Society Carrick on Shannon €646 Castlefore Development Keshcarrigan €728 Eslin Community Association Eslin €729 Gorvagh Community Centre Gorvagh €729 Gurteen Residents Association Gurteen €100 Kiltubrid Church of Ireland Restoration Kiltubrid €729 Kiltubbrid GAA Kiltubrid €729 Knocklongford Residents Association Mohill €729 Leitrim Cycle Club Leitrim Village €729 Leitrim Gaels Community Field LGFA Leitrim Village €729 Leitrim Village Active Age Leitrim Village €729 Leitrim Village Development Leitrim Village €729 Leitrim Village ICA Leitrim Village €729 Mohill GAA Mohill €729 Mohill Youth Café Mohill €729 O Carolan Court Mohill €728 Rosebank Mens Group Carrick on Shannon €410 Saint Mary’s Close Residence Association Carrick on Shannon €728 Caisleain Hamilton Manorhamilton €1,000 Dromahair Arts & Recreation Centre Dromahair €946 Killargue Community Development Association Killargue €423 Kinlough Community Garden Kinlough €1,000 Manorhamilton ICA Manorhamilton €989 Manorhamilton Rangers Manorhamilton €100 North Leitrim Womens Centre Manorhamilton €757 Sextons House Manorhamilton €1,000 Tullaghan Development Association Tullaghan €1,000 Aughavas GAA Club Aughavas €750 Aughavas Men’s Shed Aughavas €769 Aughavas Parish Improvements Scheme Aughavas -

Arthur's Way Heritage Trail

HERITAGE TRAIL Arthur’s Way is a heritage trail across northeast County Kildare that follows in the footsteps of Arthur Guinness. In just 16 km, it links many of the historic sites associated with Ireland’s most famous brewers – the Guinness family. Visitors are invited to explore Celbridge - where Arthur spent his childhood, Leixlip - the site of his first brewery and Oughterard graveyard - Arthur’s final resting place near his ancestral home. The trail rises gently from the confluence of the Liffey and Rye rivers at Leixlip to the Palladian Castletown House estate and onto Celbridge. It then departs the Liffey Valley to join the Grand Canal at Hazelhatch. The grassy towpaths guide visitors past beautiful flora and fauna and the enchanting Lyons Estate. At Ardclough, the route finally turns for Oughterard which offers spectacular views over Kildare, Dublin and the Province of Leinster. R o yaal l C a MAAYNOOTHYNOOTH nnala l R . L i e y 7 LEIXXLIXLLIP M4 6 5 N4 CELBBRIBRRIDGE DDUBLINUBLIN HHAZELHATCHAZELHAAAZZZELHATCELHHAATCH R . L i e y l a n a C d STRAFFAN n ra G NEWCASTLE 7 ARDCLOUGGHH N THHEE VVILLAGVILLAGEILLAGE AATT LLYONYONS CLLANEANE 4 RATHCOOLE OUGHTEERARDRRARDARD l 5 a nnal a C d nnd 6 a r G N7 y SSALLINSALLINS e 7 i L . R 8 9 NNAASAAS STAGES AND POINTS OF INTEREST STAGE POINTS OF INTEREST LEIXLIP to Arthur Guinness Square, Original Brewery Site, St. Mary’s Church, CELBRIDGE Leixlip Castle, The Wonderful Barn CELBRIDGE to Batty Langley Lodge, Castletown House, 22 Main Street, Oakley Park, HAZELHATCH Malting House, Celbridge Abbey, The Mill HAZELHATCH to Hazelhatch Railway Station, Hazelhatch Bridge, LYONS ESTATE The Grand Canal LYONS ESTATE to Aylmer’s Bridge, Lyons House, The Village at Lyons, OUGHTERARD Henry Bridge, Ardclough Village, Oughterard Graveyard LEIXLIP CELBRIDGE HAZELHATCH ARDCLOUGH OUGHTERARD 5 km 3 km 5 km 3 km 0 km Castletown House 5 km 8 km Lyons Estate 13 km 16 km LENGTH: 16km approx. -

Mount Kennett House, Limerick to LET - Ground & First Floors

For Sale / To Let Prime Office Investment Opportunity (Tenants not affected) Mount Kennett House, Limerick COMMERCIAL REA O’Connor Murphy www.reaoconnormurphy.ie 100 O’Connell Street +353 (0)61 279300 Limerick PSRA Licence No: 001988 Location The city of Limerick is located on the River Shannon in undergoing rapid transformation with a number of office the mid western region of Ireland within the province of and retail developments under construction including Munster. As the third largest city in Ireland, the combined Gardens International office and Bishops Quay. The main city and county population is estimated to be circa national road network and Limerick tunnel linking the city 192,000 with approximately 96,000 living within the city with the M7 Limerick to Dublin motorway and the main and suburbs. This historic city is divided from the northern Limerick to Shannon & Galway M9 motorway are all within suburbs & west of Ireland by the river Shannon with close proximity to Mount Kennett House. Surrounding access across the river via 3 main bridges and the recently occupiers include The Department of Foreign Affairs, constructed Limerick Tunnel. Holmes O’Malley Sexton Solicitors, Grant Thornton, Mazars, and Dunnes Stores. Under the Limerick Twenty Thirty plan the city is undergoing re-development, the core objective of which is Description to invest in Limerick city and county through the assembly, master planning and development of sites, thereby directly Mount Kennett House comprises a four storey over impacting employment levels and improving the general basement purpose built and fully fitted modern office socio-economic conditions of Limerick. -

Draft Limerick | Shannon METROPOLITAN AREA TRANSPORT STRATEGY 2040 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Bonneagar Iompair Eireann Transport Infrastructure Ireland Draft Limerick | Shannon METROPOLITAN AREA TRANSPORT STRATEGY 2040 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS National Transport Authority: Limerick City and County Council: Jacobs: Hugh Creegan Brian Kennedy John Paul FitzGerald David Clements Dan Slavin Kevin Burke Michael MacAree Maria Woods Marjely Caneva Jari Howard Jennifer Egan Transport Infrastructure Ireland: Robert Gallagher Sarah Cooper Martin Bourke Dara McGuigan Stephen Johnson Michael McCormack Tim Fitzgerald Colm Kelly Tara Spain Clare County Council Systra: Carmel Kirby Ian Byrne Liam Conneally Allanah Murphy Sean Lenihan Paul Hussey Ann Cronin Andrew Archer Brian McCarthy Sinead Canny John Leahy Tadgh McNamara Dolphin 3D Photomontages: Philip Watkin Date of publication: June 2020 Draft Limerick | Shannon METROPOLITAN AREA TRANSPORT STRATEGY The Strategy will deliver a high-quality, accessible, integrated and more sustainable transport network that supports the role of the Limerick-Shannon Metropolitan Area as the major growth engine of the Mid-West Region, an internationally competitive European city region and main international entry to the Atlantic Corridor. CONTENTS 01 Introduction 03 02 Policy Context 09 03 Study Area & Transport Context 19 04 Land Use 25 05 Strategy Development 29 06 Walking 33 07 Cycling 43 08 BusConnects 51 09 Rail 59 10 Roads and Streets 65 11 Parking 73 12 Freight, Delivery and Servicing 79 13 Supporting Measures 83 14 Implementation 91 15 Strategy Outcomes 95 2 LIMERICK SHANNON | METROPOLITAN AREA TRANSPORT STRATEGY 01 INTRODUCTION The Limerick-Shannon Metropolitan To mitigate this, land use and transport planning A flexible strategy with the ability to scale up Area Transport Strategy will be will be far more closely aligned.