The Professionalisation of Scottish Football Coaches: a Personal Construct Approach by Peter Thomas Clarke Thesis Submitted to T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Annual Review

2018 ANNUAL REVIEW SCOTTISH FA • 2018 ANNUAL REVIEW Scottish FA, Hampden Park, Glasgow, G42 9AY. 0141 616 6000 SCOTTISH FA ONLINE: Email: [email protected] 2018 ANNUAL REVIEW Website: www.scottishfa.co.uk Twitter: @ScottishFA CONTENTS 04 Scottish FA In Numbers IMPROVING FOOTBALL’S 06 President’s Report FINANCES 42 Financial Report PERFORMANCE OFFICE BEARERS: 44 Commercial Activities 10 JD Performance Schools President 46 Marketing And Communications 11 Project Brave Alan McRae 48 Digital Engagement 12 Pride Lab, Elite Coach Vice-President 49 Insight Rod Petrie Development, Pro Licence 50 Scotland Supporters Club Chief Executive 13 Oriam Ian Maxwell 14 National Youth Teams LEADING THE GAME as of 21 May 2018 16 Women’s National Team 54 Leading the Game 18 Men’s National Team 56 Referee Operations 20 Futsal 58 Compliance Review 21 Scottish Cup 60 Equality & Diversity 61 Children’s Wellbeing STRONG QUALITY GROWTH 62 Hampden Park Limited 24 Football for Life 63 UEFA EURO 2020 26 Cashback for Communities Designed and published 64 Scottish Football Museum 27 Tesco Bank on behalf of the 65 Hampden Sports Clinic Scottish FA by Ignition 28 Desire to Play Sports Media. www. 66 Convention 29 McDonald’s Grassroots Awards ignitionsportsmedia.com 67 Attendance Register The Scottish Football Association 30 Coach Education Limited is a private company 32 Big Lottery Fund limited by guarantee, registered in Scotland, with its registered 34 Club Development office at Hampden Park, Glasgow G42 9AY and company number 36 Para-Football SC005453. 38 The Girl’s -

A Vibrant and Diverse Festival of Talks and Events by Leading Authors Held at Your Local Libraries

a vibrant and diverse festival of talks and events by leading authors held at your local libraries. 2017 WEEK 1 Welcome to 8 – 13 MAY Booked! West Dunbartonshire’s WEEK 2 annual Festival 15 – 20 MAY of Words CONTENTS PAGE t is my privilege to introduce Ithis year’s Booked! literary festival Comic Invention 10 brought to you by West Dunbartonshire Council’s Libraries and Cultural Services Booked! Schools 19 section with sponsorship from Creative Scotland. Following on from last year’s Quick Guide: spectacular Rally and Broad event we Venues 22 will be hosting another cabaret line-up in Gartocharn’s Millennium Hall. We always Event Timetable 23 look to innovate and this year we will be Ticketing 23 incorporating our schools programme into Booked! with events in each of our High Schools. We also mark the launch of the forthcoming Comic Invention exhibition with a talk from one of Britain’s leading academics on comics and graphic novels, Dr. Mel Gibson. Booked! 2017 offers a wide range of authors, poets, and singer-songwriters and this year’s line-up has something for everyone. We are delighted to welcome Glasgow Girl Amal Azzudin, who will open the festival with our Alastair Pearson Lecture. Chitra Ramaswamy who will be talking Recently appointed as ambassador for The about her amazing book Expecting Scottish Refugee Council, and last year which is a meditation on the miracle of named as a young outstanding woman pregnancy. of Scotland by both the Young Women’s We have three treats to tempt those Movement and the Saltire Society, this will who love poetry, spoken word and be an inspiring start to the festival. -

The Professionalisation of Scottish Football Coaches: a Personal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository 1 The Professionalisation of Scottish Football Coaches: A Personal Construct Approach By Peter Thomas Clarke Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Health Sciences and Sport at the University of Stirling For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2017 2 Acknowledgements There are a number of people that need my thanks for helping me with this study. Of prime importance is Professor David Lavallee who was absolutely crucial in his ceaseless support and encouragement through the period of my study. Bob Brewer and Tony Lamb were also extremely helpful in discussing my literature chapters, making useful suggestions and corrections. Further thanks are due to two very close friends, Mal Reid and Nick Moody, two coaches with extensive knowledge of coaching at the elite elevel. Many discussions and debates on coaching have taken place with them over the many years that I have known them. Special thanks are due to my dearest friends, Tony and Maureen Lamb, who have been involved in teaching and teacher education over more years than they would like to be reminded of. Without their and their family’s unconditional support, the completion of this project would not have been possible. In addition, thanks are clearly due to the numerous players and especially the elite coaches at the various clubs where the data were collected. Without their active particpitation this work would never have come to fruition. Finally, thanks are due to my present tutor, Dr. -

Panini UK Players Collection 1992 Checklist

soccercardindex.com Panini UK Players Collection 1992 checklist England Crystal Palace Luton 160 Carl Tiler 52 Steve Coppell 107 David Pleat 161 Roy Keane Arsenal 53 Nigel Martyn 108 Alec Chamberlain 162 Garry Parker 1 George Graham 54 John Humphrey 109 Richard Harvey 163 Nigel Clough 2 David Seaman 55 Paul Bodin 110 John Dreyer 164 Gary Crosby 3 Lee Dixon 56 Lee Sinnott 111 Graham Rodger 165 Teddy Sheringham 4 Nigel Winterburn 57 Eric Young 112 Julian James 166 Nigel Jemson 5 Tony Adams 58 Andy Thorn 113 Darren McDonough 6 Steve Bould 59 Andy Gray 114 Ceri Hughes Notts County 7 David O'Leary 60 Geoff Thomas 115 David Preece 167 Neil Warnock 8 Michael Thomas 61 Mark Bright 116 Mark Pembridge 168 Steve Cherry 9 Paul Davis 62 Ian Wright 117 Kingsley Black 169 Charlie Palmer 10 David Hillier 63 John Salako 170 Alan Paris 11 David Rocastle Manchester City 171 Craig Short 12 Anders Limpar Everton 118 Peter Reid 172 Dean Yates 13 Kevin Campbell 64 Howard Kendall 119 Tony Coton 173 Don O'Riordan 14 Paul Merson 65 Neville Southall 120 Ian Brightwell 174 Phil Turner 15 Alan Smith 66 Neil McDonald 121 Neil Pointon 175 Mark Draper 67 Andy Hinchcliffe 122 Steve Redmond 176 Dave Regis Aston Villa 68 Kevin Ratcliffe 123 Keith Curle 177 Tommy Johnson 16 Ron Atkinson 69 Dave Watson 124 Colin Hendry 17 Nigel Spink 70 Alan Harper 125 Mark Brennan Oldham 18 Chris Price 71 John Ebbrell 126 David White 178 Joe Royle 19 Stuart Gray 72 Robert Warzycha 127 Niall Quinn 179 Jon Hallworth 20 Shaun Teale 73 Martin Keown 128 Adrian Heath 180 Gunnar Halle 21 Kent -

Glasgow Great Scottish Run 07-09-2003 Position Race Number

Glasgow Great Scottish Run 07-09-2003 Position Race Number Name FinishTime 1 5 Peter Kiprotich 01:01:49 2 2 Jason Mbote 01:01:49 3 3 Abner Chipu 01:01:55 4 4 Jimmy Muindi 01:01:58 5 7 Yuuki Abe 01:02:50 6 1 Sammy Kiprutu 01:03:16 7 8 Kazushi Hara 01:03:18 8 9 Leonid Shvetsov 01:04:57 9 30 Glen Stewart 01:06:17 10 20 Chris Cariss 01:06:33 11 34 Stephen Wylie 01:06:50 12 31 Allan Adams 01:07:25 13 22 Martin Scaife 01:07:50 14 21 Michael Green 01:07:52 15 102 Juan Mareque 01:09:34 16 32 Al Muir 01:09:48 17 10 Caroline Kwambai 01:10:56 18 12 Fumi Murata 01:11:02 19 135 Robert Gilroy 01:11:14 20 36 David Millar 01:11:26 21 37 Des Roache 01:11:31 22 35 Ryan Montgomery 01:12:21 23 11 Hiromi Ominami 01:12:37 24 104 Eddie Tonner 01:12:52 25 13 Yelena Burykina 01:13:26 26 105 Malcolm Bain 01:13:26 27 152 Ferens Maclean 01:13:32 28 3482 Iain Reid 01:13:52 29 165 Paul Sorrie 01:14:38 30 14 Galina Alek Sandrova 01:14:44 31 156 James Taggart 01:15:03 32 103 Dave Wright 01:15:10 33 7355 Andrew Laycock 01:15:15 34 113 Jason Barlow 01:15:18 35 41 Susan Partridge 01:15:19 36 15 Adelia Elias 01:15:45 37 57 Masahiko Takahashi 01:15:51 38 123 Andrew Cooney 01:15:52 39 42 Collette Fagan 01:16:04 40 58 Eric Negerman 01:16:04 41 139 Sean Cotter 01:16:19 42 43 Toni McIntosh 01:16:35 43 154 Nigel Grant 01:16:42 44 120 Francis Hurley 01:16:55 45 157 Ian Millar 01:16:56 46 117 Colin McKay 01:17:00 47 164 Robert McLennan 01:17:07 48 178 Alastair Maclachlan 01:17:27 49 204 Ewan Jack 01:17:37 50 168 Gordon Allsop 01:17:45 51 40 Trudi Thomson 01:17:49 52 146 Craig Stewart -

Glasgow Great Scottish Run 07-09-2003 Position

Glasgow Great Scottish Run 07-09-2003 Position Race Number Name FinishTime 1 5 Peter Kiprotich 01:01:49 2 2 Jason Mbote 01:01:49 3 3 Abner Chipu 01:01:55 4 4 Jimmy Muindi 01:01:58 5 7 Yuuki Abe 01:02:50 6 1 Sammy Kiprutu 01:03:16 7 8 Kazushi Hara 01:03:18 8 9 Leonid Shvetsov 01:04:57 9 30 Glen Stewart 01:06:17 10 20 Chris Cariss 01:06:33 11 34 Stephen Wylie 01:06:50 12 31 Allan Adams 01:07:25 13 22 Martin Scaife 01:07:50 14 21 Michael Green 01:07:52 15 102 Juan Mareque 01:09:34 16 32 Al Muir 01:09:48 17 10 Caroline Kwambai 01:10:56 18 12 Fumi Murata 01:11:02 19 135 Robert Gilroy 01:11:14 20 36 David Millar 01:11:26 21 37 Des Roache 01:11:31 22 35 Ryan Montgomery 01:12:21 23 11 Hiromi Ominami 01:12:37 24 104 Eddie Tonner 01:12:52 25 13 Yelena Burykina 01:13:26 26 105 Malcolm Bain 01:13:26 27 152 Ferens Maclean 01:13:32 28 3482 Iain Reid 01:13:52 29 165 Paul Sorrie 01:14:38 30 14 Galina Alek Sandrova 01:14:44 31 156 James Taggart 01:15:03 32 103 Dave Wright 01:15:10 33 7355 Andrew Laycock 01:15:15 34 113 Jason Barlow 01:15:18 35 41 Susan Partridge 01:15:19 36 15 Adelia Elias 01:15:45 37 57 Masahiko Takahashi 01:15:51 38 123 Andrew Cooney 01:15:52 39 42 Collette Fagan 01:16:04 40 58 Eric Negerman 01:16:04 41 139 Sean Cotter 01:16:19 42 43 Toni McIntosh 01:16:35 43 154 Nigel Grant 01:16:42 44 120 Francis Hurley 01:16:55 45 157 Ian Millar 01:16:56 46 117 Colin McKay 01:17:00 47 164 Robert McLennan 01:17:07 48 178 Alastair Maclachlan 01:17:27 49 204 Ewan Jack 01:17:37 50 168 Gordon Allsop 01:17:45 51 40 Trudi Thomson 01:17:49 52 146 Craig Stewart -

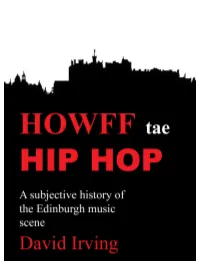

Edinburgh Scene to Be Unique, Nor Do I Think That It Has Made a Huge Contribution to World Music

HOWFF TAE HIP HOP David Irving. April 2013. David Irving asserts his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patent Acts 1988 to be identified as the author of this work. All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication, in part or in whole may be made without written permission, or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. Acknowledgements: Much of the detail within this text was checked against information contained on the Internet and in numerous periodicals and books on the period. My thanks go to all the people who created those sources. Where I have been able, I have obtained their permission and they are acknowledged at the end. Where I haven’t been able to trace them, my apologies for any inadvertent breaches of copyright which may have occurred. 1 For The Hipple People without whom ......... 2 CONTENTS Foreword 1: Shortbread and Tartan (1950-1959) 2: The First Paradiddley Dum Dum Era (1960-1966) 3: Incredible Psychedelia (1967-1969) 4: Tartan Trews and Braces (1970-1975) 5: Flying Saucers Over Arthur’s Seat (1976-1978) 6: Punk’s Still Not Dead (1979-1981) 7: Splashing In The Dolfinarium (1982-1986) 8: Some Of The Greatest Pop Never Heard (1987-1995) 9: Pioneering The Hauntological Approach (1996-2001) 10: Sending Out The S.O.S. (2002- 2011) Afterthought Acknowledgements Appendix : The Musicians and The Music 3 FOREWORD As Dee Robot of The Valves memorably pointed out, there ain’t no surf in Portobello, which is why, after we had exhausted the delights of Fun City, the Tower Amusements and Arcari’s ice-cream emporium, I and my mates Neil and Donny were at a loose end.