Remains of Basilica at Lyminge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Folkestone School for Girls

Buses serving Folkestone School for Girls page 1 of 6 via Romney Marsh and Palmarsh During the day buses run every 20 minutes between Sandgate Hill and New Romney, continuing every hour to Lydd-on-Sea and Lydd. Getting to school 102 105 16A 102 Going from school 102 Lydd, Church 0702 Sandgate Hill, opp. Coolinge Lane 1557 Lydd-on-Sea, Pilot Inn 0711 Hythe, Red Lion Square 1618 Greatstone, Jolly Fisherman 0719 Hythe, Palmarsh Avenue 1623 New Romney, Light Railway Station 0719 0724 0734 Dymchurch, Burmarsh Turning 1628 St Mary’s Bay, Jefferstone Lane 0728 0733 0743 Dymchurch, High Street 1632 Dymchurch, High Street 0733 0738 0748 St. Mary’s Bay, Jefferstone Lane 1638 Dymchurch, Burmarsh Turning 0736 0741 0751 New Romney, Light Railway Station 1646 Hythe, Palmarsh Avenue 0743 0749 0758 Greatstone, Jolly Fisherman 1651 Hythe, Light Railway Station 0750 0756 0804 Lydd-on-Sea, Pilot Inn 1659 Hythe, Red Lion Square 0753 0759 0801 0809 Lydd, Church 1708 Sandgate Hill, Coolinge Lane 0806 C - 0823 Lydd, Camp 1710 Coolinge Lane (outside FSG) 0817 C - Change buses at Hythe, Red Lion Square to route 16A This timetable is correct from 27th October 2019. @StagecoachSE www.stagecoachbus.com Buses serving Folkestone School for Girls page 2 of 6 via Swingfield, Densole, Hawkinge During the daytime there are 5 buses every hour between Hawkinge and Folkestone Bus Station. Three buses per hour continue to Hythe via Sandgate Hill and there are buses every ten minutes from Folkestone Bus Station to Hythe via Sandgate Hill. Getting to school 19 19 16 19 16 Going -

A Guide to Parish Registers the Kent History and Library Centre

A Guide to Parish Registers The Kent History and Library Centre Introduction This handlist includes details of original parish registers, bishops' transcripts and transcripts held at the Kent History and Library Centre and Canterbury Cathedral Archives. There is also a guide to the location of the original registers held at Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre and four other repositories holding registers for parishes that were formerly in Kent. This Guide lists parish names in alphabetical order and indicates where parish registers, bishops' transcripts and transcripts are held. Parish Registers The guide gives details of the christening, marriage and burial registers received to date. Full details of the individual registers will be found in the parish catalogues in the search room and community history area. The majority of these registers are available to view on microfilm. Many of the parish registers for the Canterbury diocese are now available on www.findmypast.co.uk access to which is free in all Kent libraries. Bishops’ Transcripts This Guide gives details of the Bishops’ Transcripts received to date. Full details of the individual registers will be found in the parish handlist in the search room and Community History area. The Bishops Transcripts for both Rochester and Canterbury diocese are held at the Kent History and Library Centre. Transcripts There is a separate guide to the transcripts available at the Kent History and Library Centre. These are mainly modern copies of register entries that have been donated to the -

The Lyminge Newsletter

THE LYMINGE NEWSLETTER For the communities of LYMINGE, ETCHINGHILL, RHODES MINNIS and POSTLING Produced by THE LYMINGE ASSOCIATION April 2020 www.lyminge.org.uk From The Lyminge Association as accurate as possible when going to print - 23 March Trying to write a newsletter when there is so much going on in our lives it’s very difficult particularly when looking for the positives. We are certainly very lucky to live the living where we are in the countryside and with a very helpful and supportive community. As many of our community are going into self-isolation we are encouraged by the way others are willing and selflessly able to support them. However, now it’s not the time to forget the announcement you hear on planes “to put on your face mask before helping others“ which is very important in this current climate. Many of the events originally planned have been cancelled or suspended. The newsletter tries to reflect as accurately as possible the state of these particular events but I would recommend you check on their availability. On P4 and 9 you will find takeaway menus for both The Coach and Horses and The Gatekeeper. These, together with the other takeaways in our area, are to be applauded for providing a service; so please support them as best as you are able in order to maintain their business. On P17 you will find the details on how to maintain your health under the current circumstances. Needless to say these may have already been updated and I would encourage you to keep in touch with the government and NHS news releases. -

How Lyminge Parish Church Acquired an Invented Dedication

ANTIQUARIANS, VICTORIAN PARSONS AND RE-WRITING THE PAST: HOW LYMINGE PARISH CHURCH ACQUIRED AN INVENTED DEDICATION ROBERT BALDWIN For more than a century, the residents of Lyminge, on the North Downs in East Kent, have taken for granted that the parish church is dedicated to St Mary and St Ethelburga. Yet for many centuries before that, it was known as the church of St Mary and St Eadburg. The dedication to St Mary, the Virgin, is ancient and straightforward to explain, for it appears in the earliest of the surviving charters forLyminge dated probably to 697. 1 The second part of the dedication, whether this is correctly St Ethelburga or St Eadburg, is also likely to pre-date the Norman Conquest for both are clearly Anglo-Saxon names. But the uncertainty over the dedication invites investigation to understand who the patron saint actually is and the cause of the change, which is an unusual event by any standards. At first sight, St Ethelburga is apparently also easy to explain. Although there were a number of St Ethelburgas, the one traditionally connected with Lyminge was Queen LEthelburh2, daughter of LEthelberht I, King of Kent, and widow of Edwin, King of Northumbria. The story of her marriage to Edwin, his conversion to Christianity and the beginning of the conversion of Northumbria in the 620s was recorded by Bede, writing around a century later.3 AfterEdwin's death in battle in 633, Bede noted that LEthelburh returned to Kent where her brother Eadbald had become king. Other sources4 recounted that the king allowed his sister to retire to his estate at Lyminge where she established a 'minster'5 and subsequently died in 647.6 A dedication to St Ethelburga makes sense in the historical context ofLyminge. -

Folkestone & Hythe District Heritage Strategy

Folkestone & Hythe District Heritage Strategy Appendix 1: Theme 11 Archaeology PROJECT: Folkestone & Hythe District Heritage Strategy DOCUMENT NAME: Appendix 1 - Theme 11: Archaeology Version Status Prepared by Date V01 INTERNAL DRAFT F Clark 08.03.16 Comments – First draft of text. No illustrations or figures. Need to finalise references and check stats included. Need to check structure of Descriptions of Heritage Assets section. May also need additions from other theme papers to add to heritage assets – for example defence heritage. Version Status Prepared by Date V02 INTERNAL DRAFT F Clark 23.08.17 Comments – Same as above with some corrections throughout. Version Status Prepared by Date V03 RETURNED DRAFT D Whittington 16.11.18 Update back from FHDC Version Status Prepared by Date V04 CONSULTATION S MASON 29.11.18 DRAFT Final check and tidy before consultation – Title page added, pages numbered 2 | P a g e Appendix 1, Theme 11 - Archaeology 1. Summary The district is rich in archaeological evidence beginning from the first occupations by early humans in Britain 800,000 years ago through to the twentieth century. The archaeological remains are in many forms such as ruins, standing monuments and buried archaeology and all attest to a distinctive Kentish history as well as its significant geographical position as a gateway to the continent. Through the district’s archaeology it is possible to track the evolution of Kent as well as the changing cultures, ideas, trade and movement of different peoples into and out of Britain. The District’s role in the defence of the country is also highlighted in its archaeology and forms an important part of the archaeological record for this part of the British southern coastline. -

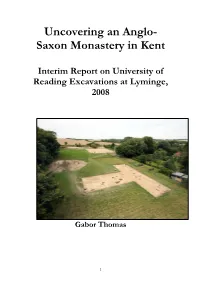

Saxon Monastery in Kent

Uncovering an Anglo- Saxon Monastery in Kent Interim Report on University of Reading Excavations at Lyminge, 2008 Gabor Thomas 1 Landscapes of the Anglo-Saxon Conversion: University of Reading Excavations at Lyminge, Kent, 2008 The following presents provisional results of the inaugural year of open-area excavation by the University of Reading within the precincts of the Anglo-Saxon monastic site of Lyminge, Kent. This work forms part of a wider project entitled ‘Landscapes of Conversion: the Anglo-Saxon Church within the Kingdom of Kent’, which seeks to construct a comparative framework in which to interpret and contextualize the evidence garnered from Lyminge. Historical and archaeological background The historical context surrounding the Anglo-Saxon monastery of St Mary’s, Lyminge has received full treatment in the Project Design (Thomas 2005). Since the initiation of the excavations a critical analysis of the historical sources relating to Lyminge minster has appeared in print (Kelly 2006). Kelly’s detective work has shaken many of the ‘truths’ surrounding the foundation legend of Lyminge minster derived from the largely post-Conquest hagiographical tradition associated with the Kentish saint, Mildrith (Rollason 1982). It is from this source that Lyminge derives its association with its founding abbess, the historical figure, Æthelburh, widow of King Edwin of Northumbria and daughter of King Æthelberht I of Kent, and with her its foundation date of A.D. 633. Contrary to received wisdom, Kelly points out that a Christian site of this comparatively early date was more likely to have been non-monastic in character, perhaps taking the form of a royal mortuary chapel. -

On a Roman Hypocaust Discovered at Folkestone in 1875

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 10 1876 ( 173 ) ON A ROMAN HYPOCATJST DISCOVERED AT FOLKESTONE, A.D. 1875. BY CANON R. 0. JENKINS, RECTOR OF LYMINGKE. IT will be within the recollection of those members of our Society who were at the meeting at Folkestone, that their attention was directed to the recent dis- covery of the foundations of a church or chapel, apparently of Romano-British origin, in a field adjoin- ing the Upper Station, at the eastern end of the town. These remains of early building, through the kind- ness of the proprietor (Mr. Major, of Folkestone), were left open for some time, and an opportunity was thus given for their fuller inspection. Unfortunately no ground-plan was taken, so that the only record of them is in the memories of those who saw them during the period of their exposure. Since then they have shared the fate which usually befals relics of antiquity in a rapidly increasing town. The founda- tion has been broken up, and removed for building purposes, and the ancient stones, covered with an almost imperishable concrete, will probably be hidden anew among the foundations of modern Folkestone. By many this early religious foundation was sup- posed to be that of the Chapel of St. Botolph, respecting which various records still exist; but it is difficult, without further evidence, to identify it, 174 ON A ROMAN HTPOOAUST though the character of the masonry, in which Roman "bricks of a large size were occasionally found as bonding courses, and the structure of the concrete, point to a very remote antiquity. -

Monasteries and Places of Power in Pre Viking England: Trajectories

Monasteries and places of power in pre- Viking England: trajectories, relationships and interactions Book or Report Section Published Version Thomas, G. (2017) Monasteries and places of power in pre- Viking England: trajectories, relationships and interactions. In: Thomas, G. and Knox, A. (eds.) Early medieval monasticism in the North Sea Zone: proceedings of a conference held to celebrate the conclusion of the Lyminge excavations 2008-15. Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History, 20. Oxford University School of Archaeology, Oxford, pp. 97-116. ISBN 9781905905393 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/70249/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher's version if you intend to cite from the work. Publisher: Oxford University School of Archaeology All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading's research outputs online An offprint from Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 20 EARLY MEDIEVAL MONASTICISM IN THE NORTH SEA ZONE Proceedings of a conference held to celebrate the conclusion of the Lyminge excavations 2008–15 Edited by Gabor Thomas and Alexandra Knox General Editor: Helena Hamerow Oxford University School of Archaeology Published by the Oxford University School of Archaeology Institute of Archaeology Beaumont Street Oxford -

THE LYMINGE NEWSLETTER for the Communities of LYMINGE, ETCHINGHILL, RHODES MINNIS and POSTLING

THE LYMINGE NEWSLETTER For the communities of LYMINGE, ETCHINGHILL, RHODES MINNIS and POSTLING Produced by THE LYMINGE ASSOCIATION April 2018 www.lyminge.org.uk The Lyminge Association brings you: STREAM CLEAN 7th April Well Field - 10am start Your chance to get wet, muddy and smiley as you help clear some vegetation and debris from a few of the water courses in the village. LYMINGE LITTER PICK Since the previous litter pick was postponed because of the poor weather, it has been rescheduled for Saturday 5th May Jointly sponsored by The Lyminge Association and Lyminge Parish Council, it will start from Lyminge Village Hall at 10am The Lyminge Association (LA) plays a significant role in shaping the communities in which we live. Often this is by way of the monthly Newsletter and a number of one-off events such as the Musical Evening, Garage Safaris, Stream Clean, etc. All profits are fed back into the community via grants or donations. This year, the LA is sponsoring a Junior Dragon’s Den giving young people an opportunity to secure funding for projects. There will be five £100 grants. Projects should aim to bring benefit to the community within the area of Lyminge, Etchinghill, Rhodes Minnis and Postling and entry is open to any age group (8-18 years of age) within the community. Applications are invited from groups of young people or individuals and they will be judged by a panel of six, made up of 3 young people and 3 committee members plus a chair. Now’s the time to start about possible projects!! Full details and application forms will be available from The Editor in late April and the event will take place in the Tayne Centre on 23rd June at 2pm. -

Newsletter.Pdf

E L H A M NEWSLETTE R Published by the Elham Village Hall Association, Charity No 1024757 Also available to read on the EVHA website, www.elhamvillagehall.co.uk. For further information www.elham.co.uk/ visit Elham OCTOBER 2021 Summer Meadow, picture by Hugh Carson, originally sent for ‘Talk on the Wild Side, 2020. What’s On, In and Around ELHAM Date Event Time Location Contact Page Saturday 2nd Elham Gardening Society Coffee Doug Martin 01303 tbc Elham Village Hall 13 October Morning and Bulb Sale 840276 Maggie Tappenden Monday 4th October Short Mat Bowls Begins Again 15.30 -18.00 Elham Village Hall 01303 862467 25 Anna Clayton Jim Clements Monday 4th October Table Tennis for All 19.00 25 Room EVH 01303840295 Wednesday 6th Social, Snacks and Cinema Peggy Pike Room Jan Stanyon 19.00 5 October EVHA Elham Village Hall 01303 840820 ST MARY’S CHURCH HALL Nicki’s Garden Design and Maintenance For parties, for the smaller function Hadlow Horticultural College and for Meetings trained and qualified More than fifteen years experience £12.00 for Mornings and Afternoons Garden Designing and planting from whole garden project to re-designing tired borders £15.00 for Evenings and Saturdays General Maintenance, Weeding, Pruning, Use of Kitchen included Planting, Lawn Mowing, Hedge Cutting Gardening can be provided on a weekly, fortnightly or Bookings: Mrs Pat Holmes seasonal basis 01303 840647 Call Nicki on 07748628993 Email: [email protected] Do you need a helping hand? Garden & Domestic Work House & Pet Sitting Small Animal Care Then please ’phone Fiona Johnson 01303 840507 (working locally for 28 years) Air Link Cars Airport, Seaport & Long Distance Travel Specialist The family run business where service really counts. -

18 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

18 bus time schedule & line map 18 Canterbury View In Website Mode The 18 bus line (Canterbury) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Canterbury: 7:15 AM - 5:10 PM (2) Hythe: 8:55 AM - 6:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 18 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 18 bus arriving. Direction: Canterbury 18 bus Time Schedule 45 stops Canterbury Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:15 AM - 5:10 PM Hythe Light Railway Station Hythe (DA) Tuesday 7:15 AM - 5:10 PM Sir John Moore Avenue, Hythe Wednesday 7:15 AM - 5:10 PM Red Lion Square, Hythe Thursday 7:15 AM - 5:10 PM Dymchurch Road, Hythe Civil Parish Friday 7:15 AM - 5:10 PM Old Prospect Road, Hythe Prospect Road, Hythe Civil Parish Saturday 7:20 AM - 5:10 PM Douglas Avenue, Hythe A259, Hythe Civil Parish Saltwood Care Centre, Hythe 18 bus Info Tanners Hill, Hythe Civil Parish Direction: Canterbury Stops: 45 Tanner's Hill Gardens, Hythe Trip Duration: 61 min Tanners Hill, Hythe Civil Parish Line Summary: Hythe Light Railway Station Hythe (DA), Sir John Moore Avenue, Hythe, Red Lion School Road, Hythe Square, Hythe, Old Prospect Road, Hythe, Douglas Avenue, Hythe, Saltwood Care Centre, Hythe, Quarry Road, Hythe Tanner's Hill Gardens, Hythe, School Road, Hythe, Quarry Road, Hythe, Hillcrest Road Middle, Hythe, Hillcrest Road Middle, Hythe Hillcrest Road, Saltwood, Brockhill Road, Saltwood, Seaton Avenue, Saltwood, Bartholomew Lane, Hillcrest Road, Saltwood Saltwood, Brockhill Park, Saltwood, Railway Station, Sandling, -

HAWKINGE ANNUAL TOWN MEETING – 10Th April 2018

HAWKINGE ANNUAL TOWN MEETING – 10th April 2018 Minutes of the Hawkinge Annual Town Meeting held on 10th April 2018, at Hawkinge Community Centre, Heron Forstal Avenue, Hawkinge. Councillor J Heasman, Town Mayor, was in the Chair. Present: Councillors J Heasman, G Hibbert, D Pascoe, G Ward, A Csiszar, L Palliser, P Martin, G Ward, D Godfrey, D Callahan. In attendance: Mrs T Wiles, Town Clerk; Mrs J Abbott, Financial & Project Officer and Miss L Cook, Administrative Assistant. There were 47 members of the public present. The Chairman opened the meeting and welcomed the guests and members of the local community. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Cllr S Manion, Cllr S Peall. MINUTES The Minutes of the Annual Town Meeting held on 11 April 2017, were submitted and approved as a correct record and signed by the Chairman. REPORT OF THE TOWN MAYOR OF HAWKINGE The Town Mayor Councillor John Heasman presented his report, copy attached at APPENDIX 1. REPORT OF KENT COUNTY COUNCILLOR Kent County Councillor Susan Carey delivered her annual report, and copies were distributed to those present. Copy attached at APPENDIX 2. REPORT OF FOLKESTONE AND HYTHE DISTRICT COUNCILLORS The Report of the District Councillors was presented by District Councillor David Godfrey, copies were distributed to those present. Copy attached at APPENDIX 3. ANY OTHER BUSINESS Questions raised to Susan Carey, Kent County Councillor: Q. The HGVS are making to road unsafe to use, would it be possible to have a restriction on high and weight of the A260? A. Unfortunately, this a main route that HGVS are directed to use therefore restrictions would not be approved.