1 Policing Shit, Or, Whatever Happened To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HUD Consolidated Plan

2018 – 2022 CONSOLIDATED PLAN CITY OF BELLINGHAM, WASHINGTON (covering the period from July 1, 2018 – June 30, 2023) May 29, 2018 This version of the Bellingham Consolidated Plan uses the organization and tables required by HUD’s Integrated Disbursement and Information System (IDIS). For a more user-friendly document, please view the Public version of the Consolidated Plan draft, published simultaneously, and available in the same locations as this version (online, at the Planning Department, and in the Bellingham Library branches). Please contact the Community Development Division, Department of Planning & Community Development, at [email protected] with any questions or comments, or visit http://www.cob.org. Consolidated Plan BELLINGHAM 1 OMB Control No: 2506-0117 (exp. 06/30/2018) This page is intentionally blank. Consolidated Plan BELLINGHAM 2 OMB Control No: 2506-0117 (exp. 06/30/2018) Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 6 ES-05 Executive Summary - 24 CFR 91.200(c), 91.220(b) ......................................................................... 6 The Process ................................................................................................................................................. 12 PR-05 Lead & Responsible Agencies 24 CFR 91.200(b) ........................................................................... 12 PR-10 Consultation - 91.100, 91.200(b), 91.215(l) ................................................................................ -

Nineteen Hundred Fifty-Two. Sixtieth Annual Report of the City of Laconia

XltbgralHrts fflxt TtLtttbtr&itp NINETEEN HUNDRED FIFTY -TWO + + + Sixtieth Annual Report of the CITY OF LACONIA NEW HAMPSHIRE for the Year Ending June 30, 1953 UNDER THE ADMINISTRATIONS OF Honorable Robinson W. Smith, Mayor and Councilmen Leo G. Roux NAUCURAL ADDRESS OF THE Honorable Gerard L Morin Thank you Mayor Smith, Members of the Clergy, Invited Guests, Members of the Outgoing Council, Members of the Board of Education, Gentlemen of the Council, Ladies and Gentlemen. In the exercise of your power and right of self-government, you have committed to me, one of your fellow citizens, a supreme and sacred trust —and I dedicate myself to your service. There is no legal requirement that the Mayor take the oath of office in the presence of the people, but I feel it is appropriate that the people of Laconia be invited to witness this solemn ceremonial. It affects a tie—a sort of convenant between the people of Laconia and its chief executive. I convenant to serve the whole body of our citizenry by a faithful execution of the duties of a Mayor as prescribed by law. Thus, my promise is spoken—yours un- spoken, but nevertheless real and solemn. May Almighty God give me wisdom, strength and fidelity. Let us pause for a moment in memory of those individuals who have, in the past, rendered public service—have unselfishly given of their time r and who have passed away during the past tw o years : George R. Bow- man, John O'Connor, Frederick Brockington, Perley Avery, William Kempton, Max Chertok, Albert R. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Emergency Medical Services at the Crossroads

Future of Emergency Care Series Emergency Medical Services At the Crossroads Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System Board on Health Care Services PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. This study was supported by Contract No. 282-99-0045 between the National Academy of Sciences and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); Contract No. B03-06 between the National Academy of Sciences and the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation; and Contract No. HHSH25056047 between the National Academy of Sciences and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the organizations or agencies that provided support for this project. International Standard Book Number 0-309-XXXXX-X (Book) International Standard Book Number 0-309- XXXXX -X (PDF) Library of Congress Control Number: 00 XXXXXX Additional copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press, 500 Fifth Street, N.W., Lockbox 285, Washington, DC 20055; (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313 (in the Washington metropolitan area); Internet, http://www.nap.edu. -

Medical Police and the History of Public Health

Medical History, 2002, 46: 461494 Medical Police and the History of Public Health PATRICK E CARROLL* These hovels were in many instances not provided with the commonest conveniences of the rudest police; contiguous to every door might be observed the dung heap on which every kind of filth was accumulated .. .1 In 1942, Henry Sigerist questioned the idea that "the German way in public health was to enforce health through the police while the English way consisted in acting through education and persuasion".2 Contrasts of this kind have, however, remained commonplace throughout the twentieth century.3 In the 1950s, George Rosen sought to reframe the history of public health in order to understand how it "reflected" its social and historical context. Despite critiques ofRosen's Whiggism, his work remains a source of current contrasts between public health and medical police. Rosen's analysis posited an inherent relationship between the idea of medical police and those of cameralism4 and mercantilism, particularly as developed in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Germany.' Treating cameralism and medical police as "super- structural" forms subordinate to the political and economic relations of the ancien regime, he concluded that medical police was essentially a centralized form of continental and despotic government. It was incompatible with the forms of liberal * Patrick Carroll, MA, PhD, Department of 3W F Bynum and Roy Porter (eds), Medical Sociology, One Shields Avenue, University of fringe & medical orthodoxy 1750-1850, London, California, Davis CA 95616, USA. E-mail: Croom Helm, 1987, pp. 187, 196 n. 33; [email protected]. Christopher Hamlin, Public health and social justice in the age of Chadwick: Britain 1800-1854, The research was facilitated by a Faculty Cambridge University Press, 1998. -

ANNUAL REPORT Department Town of Burlington Telephone (Area Code 781) E-Mail/Web Address Burlington Web

2010 TOWN OF BURLINGTON BURLINGTON, MASSACHUSETTS DIRECTORY ANNU A L REPO L ANNUAL REPORT Department Town of Burlington Telephone (Area Code 781) E-mail/Web Address Burlington Web ........................................................... www.burlington.org OF THE TOWN OFFICERS / YEAR ENDING DECEMBER 2010 Information/Connecting all Departments ............................. 270-1600 Main Fax Number Connecting Offices ............................... 270-1608 R Accounting ...................................................... 270-1610. [email protected] T Assessors ....................................................... 270-1650. [email protected] BCAT ........................................................... 273-5922. [email protected] BCAT Web ................................................................ www.bcattv.org B-Line Information ............................................... 270-1965 Board of Health Public Nurse ................................................. 270-1957 Sanitarian/Environmental Engineer .............................. 270-1954. [email protected] Building Inspector ................................................ 270-1615. [email protected] Community Life Center ............................................ 270-1961. [email protected] Conservation Commission ......................................... 270-1655. [email protected] Council On Aging ................................................ 270-1950. [email protected] C.O.A. Lunch Line ............................................... -

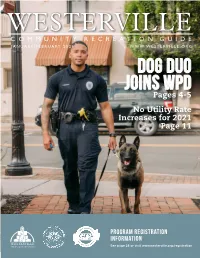

Dog Duo Joins WPD Pages 4-5 No Utility Rate Increases for 2021 Page 11

WESTERVILLE COMMUNITY RECREATION GUIDE JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2021 WWW.WESTERVILLE.ORG Dog Duo JoiNS WPD Pages 4-5 No Utility Rate Increases for 2021 Page 11 PROGRAM REGISTRATION INFORMATION parks & recreation See page 28 or visit www.westerville.org/registration 1 WESTERVILLE PARKS AND RECREATION DEPARTMENT • (614) 901-6500 • www.westerville.org PB Welcome Welcome to 2021, and let’s hope we can officially deem this the year of recovery. If you’re a Parks and Recreation family, this is the year for you! Starting with this issue, the Guide is now on a bi-monthly schedule, which means you’ll get one publication every other month (instead of quarterly) and MORE opportunities than ever before to register for programs and drop-in events and classes. The expanded Community Center is now open and operational, and the reviews are in. “Practically brand new,” WESTERVILLE “beautiful,” “expectations exceeded” are what we’re hearing CITY COUNCIL from guests. Visit www.westerville.org/onepass to sign up or schedule a tour. BACK ROW: Alex Heckman; Valerie Cumming, Vice Mayor; Diane Conley; Kenneth Wright The new year is also kicking off with new management for FRONT ROW: Craig Treneff, Vice Chair; Kathy the City of Westerville. We welcome Monica Irelan to the Cocuzzi, Mayor; Mike Heyeck, Chair City. Monica begins her term as City Manager this month, replacing David Collinsworth, who recently retired. Assistant City Manager Julie Colley retires at the end of the month, and Irelan is expected to name her replacement soon. Learn more about Irelan on page 6, and expect a full feature on her new role and objectives in the March/April issue. -

Administration of Retinal S Antigen As an Oral Tolerizing Ofrapport, the Benefit Is Less Clear, Particularly in the Later Agent

Postgraduate Medical Journal EDITOR B.I. HofTbrand, London ASSISTANT EDITOR P.J.A. Moult, London EDITORIAL BOARD J. Bamford, Leeds K.T. Khaw, Cambridge P.J. Barnes, London R.I. McCallum, Edinburgh A.H. Barnett, Birmingham P.H. Millard, London G.F. Batstone, Salisbury M.W.N. Nicholls, London C.J. Bulpitt, London N.T.J. O'Connor, Shrewsbury C. Coles, Southampton M. Sarner, London G.C. Cook, London M. Super, Manchester P.N. Durrington, Manchester I. Taylor, London J.C. Gingell, Bristol T. Treasure, London T.E.J. Healy, Manchester P. Turner, London C.R.K. Hind, Liverpool I.V.D. Weller, London D. Ingram, London P.D. Welsby, Edinburgh C.D. Johnson, Southampton W.F. Whimster, London P.G.E. Kennedy, Glasgow P.R. Wilkinson, Ashford, Middx National Association of Clinical Tutors Representatives I.J.T. Davies, Inverness R.D. Abernethy, Barnstaple International Editorial Representatives G.J. Schapel, Australia P. Tugwell, Canada J.W.F. Elte, The Netherlands E.S. Mayer, USA F.F. Fenech, Malta B.M. Hegde, India C.S. Cockram, Hong Kong Editorial Assistant Mrs J.M. Coops Volume 69, Number 818 December 1993 The Postgraduate Medical Journal is published Subscription price per volume oftwelve issues EEC monthly on behalf ofthe Fellowship of Postgraduate £E130.00; Rest ofthe World £140.00 or equivalent in Medicine by the Scientific & Medical Division, any other currency. Orders must be accompanied by Macmillan Press Ltd. remittance. Cheques should be made payable to Macmillan Press, and sent to: the Subscription Postgraduate Medical Journal publishes original Department, Macmillan Press Ltd, Brunel Road, papers on subjects ofcurrent clinical importance. -

Title # of Eps. # Episodes Male Caucasian % Episodes Male

2020 DGA Episodic TV Director Inclusion Report (BY SHOW TITLE) # Episodes % Episodes # Episodes % Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # of % Episodes % Episodes % Episodes % Episodes Male Male Female Female Title Male Males of Female Females of Network Studio / Production Co. Eps. Male Caucasian Males of Color Female Caucasian Females of Color Unknown/ Unknown/ Unknown/ Unknown/ Caucasian Color Caucasian Color Unreported Unreported Unreported Unreported 100, The 12 6.0 50.0% 2.0 16.7% 3.0 25.0% 1.0 8.3% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% CW Warner Bros Companies Paramount Pictures 13 Reasons Why 10 6.0 60.0% 2.0 20.0% 2.0 20.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% Netflix Corporation Paramount 68 Whiskey 10 7.0 70.0% 0.0 0.0% 3.0 30.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% Network CBS Companies 9-1-1 18 4.0 22.2% 6.0 33.3% 5.0 27.8% 3.0 16.7% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% FOX Disney/ABC Companies 9-1-1: Lone Star 10 5.0 50.0% 2.0 20.0% 3.0 30.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% FOX Disney/ABC Companies Absentia 6 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 6.0 100.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% Amazon Sony Companies Alexa & Katie 16 3.0 18.8% 3.0 18.8% 5.0 31.3% 5.0 31.3% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% Netflix Netflix Alienist: Angel of Darkness, Paramount Pictures The 8 5.0 62.5% 0.0 0.0% 3.0 37.5% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% TNT Corporation All American 16 4.0 25.0% 8.0 50.0% 2.0 12.5% 2.0 12.5% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% CW Warner Bros Companies All Rise 20 10.0 50.0% 2.0 10.0% 5.0 25.0% 3.0 15.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% CBS Warner Bros Companies Almost Family 12 6.0 50.0% 0.0 0.0% 3.0 25.0% 3.0 25.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% FOX NBC Universal Electric Global Almost Paradise 3 3.0 100.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% WGN America Holdings, Inc. -

Open-Ended Question: “How Do You — Patty Fernandez-Andres in Years Past, National Public Safety Encourage Someone to Overcome the Stress “Don't Give Up

INTERNATIONAL ACADEMIES OF EMERGENCY DISPATCH MAY | JUNE 2017 FIRST ACE STILL PROPER SUICIDE SAVING A LIFE 10 | GOING STRONG 32 | INTERVENTION 44 | AFTER HOURS PAGE | 17 EXCELLENCE IS KEY iaedjournal.org get the right information. ProQA® Paramount structured calltaking means all the right information is gathered. at the right time. Faster calltaking time means shorter time to dispatch. to the right people –every call. That means faster, safer responders and safer communities. prioritydispatch.net | 800.363.9127 • •• COLUMNS MAY • JUNE 2017 | VOL. 21 NO. 3 4 | contributors 5 | the skinny 6 | dear reader 7 | from the emd side 8 | ask doc 9 | research • •• SECTIONS BEST PRACTICES 10 | ace achievers 13 | center piece 15 | faq ON TRACK 32 | police cde 36 | medical cde 40 | blast from the past YOUR SPACE 43 | dispatch in action • •• FEATURES CASE EXIT 17 | fast facts—NAVIGATOR 46 | after the accident 18 | NAVIGATOR 2017 Another amazing NAVIGATOR event inspired and educated. See what happened at this year’s conference in New Orleans. 26 | APPS FOR DISPATCH A handful of smartphone apps are now available to help comm. centers provide enhanced service to their callers. COVER PHOTO BY JOSHUA BRASTED Follow IAED on social media. The following U.S. patents may apply to portions of the MPDS or software depicted in this periodical: 5,857,966; 5,989,187; 6,004,266; 6,010,451; 6,053,864; 6,076,065; 6,078,894; 6,106,459; 6,607,481; 7,106,835; 7,428,301; 7,645,234. The PPDS is protected by U.S. patent 7,436,937. -

PRESS ADVISORY December 3, 2019 OWN ANNOUNCES

PRESS ADVISORY December 3, 2019 OWN ANNOUNCES ADDITIONAL CAST AND DIRECTORIAL LINE-UP FOR AWARD-WINNING CREATOR AVA DuVERNAY’S NEW ORIGINAL ANTHOLOGY DRAMA ‘CHERISH THE DAY’ Michael Beach, Anne-Marie Johnson and Kellee Stewart Join the Cast of the New Drama Premiering Winter 2020 Directors Include Blitz Bazawule, Aurora Guerrero and Deborah Kampmeier Photo caption: (L to R) Michael Beach, Anne-Marie Johnson, Kellee Stewart Photo caption: Directors (L to R) Blitz Bazawule, Aurora Guerrero and DeBorah Kampmeier Los Angeles – OWN: Oprah Winfrey Network announceD toDay the Directorial lineup anD aDDitional casting for the first installment of the anticipateD new romantic anthology Drama “Cherish the Day,” createD anD executive produced by Emmy® winner/AcaDemy AwarD®-nominee Ava DuVernay (“Queen Sugar,” “When They See Us”). The series from Warner Horizon ScripteD Television aDDeD Michael Beach, Anne-Marie Johnson and Kellee Stewart in recurring roles. They join previously announced series regulars Xosha Roquemore, Alano Miller and legendary Emmy®-winning actress Cicely Tyson. The DuVernay leD series recently announceD it achieved full gender parity with a production crew of over 50% women, including 18 female department heaDs. Directors Blitz Bazawule, Aurora Guerrero anD Deborah Kampmeier join previously announceD director Tanya Hamilton. Chapter one of “Cherish the Day” chronicles the stirring relationship of one couple, with each episode spanning a single day. The narrative will unfold to reveal significant moments in a relationship that compel us to hold true to the ones we love, from the extraordinary to the everyday. Xosha Roquemore (“The Mindy Project”) stars as Gently James anD Alano Miller (“UnDergrounD”) stars as Evan Fisher. -

Medical Licensing in Late-Medieval Portugal

This is a repository copy of Medical licensing in late-medieval Portugal. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/80829/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: McCleery, IM (2014) Medical licensing in late-medieval Portugal. In: Turner, WJ and Butler, SM, (eds.) Medicine and Law in the Middle Ages. Brill , 196 - 219. ISBN 9789004269064 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ chapter 8 Medical Licensing in Late Medieval Portugal Iona McCleery1 On 11 February 1338, Aires Vicente was licensed to practice surgery by the chief-examiner Master Afonso, Master Domingos, “expert in the art of coughs,” and apothecary-surgeons Master Gil and Master Pero.2 A few days later on 22 February, Master Domingos was himself licensed in surgery by chief- examiners Master Afonso and Master Gonçalo.