Statutory Acknowledgements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TP146 Kaipara River Catchment Water Allocation Strategy 2001 Part D

D – Supporting Information 135 References Chapter 1 Auckland Regional Council, 1999. Auckland Regional Policy Statement. Auckland Regional Water Board, 1984. Kaipara River Freshwater Resource Report and Interim Management Plan. Technical Publication No 27. Auckland Regional Water Board, 1989. Kaipara River Catchment Water and Allocation Plan. Technical Publication No 56. Chapter 2 Auckland Regional Council, 1991. Transitional Regional Plan. Auckland Regional Council, 1995. Proposed Regional Plan: Coastal. Auckland Regional Council, 1995. Proposed Regional Plan: Sediment Control. Auckland Regional Council, 1999a. Auckland Regional Policy Statement. Auckland Regional Council, 1999b. Regional Plan: Farm Dairy Discharges. Chapter 4 Auckland Regional Council, 1995. Kumeu-Hobsonville Groundwater Resource Assessment Report. New Zealand Meteorological Service, 1983. Climate Regions of New Zealand, Miscellaneous Publication No 174. Chapter 5 Section 5.1 Auckland Regional Council, 1995 History of Human Occupation. Hoteo River Catchment Resource Statement: Working Report. Auckland Regional Council, 1998. Rural Information System Farm Details. Auckland Regional Water Board, 1984. Kaipara River Freshwater Resource Report and Interim Management Plan. Technical Publication No 27. 136 Auckland Regional Water Board, 1989. Kaipara River Catchment Water and Allocation Plan. Technical Publication No 56. Beca Carter Hollings&Ferner Ltd, 1989. Kaipara River Flood Management Plan 1989 Beever J. A map of the Pre European vegetation of Lower Northland (in NZ Journal of Botany Vol.19 Best, S.B 1994 Rautawhiri Park Development Archaeological Survey. Unpublished Site Survey Report for Works Consultancy Ltd, Auckland. Best S.B. 1975 Site Recording in the Southern half of the South Kaipara Peninsula. New Zealand Historic Places Trust, Wellington. Best, S.B 1995 Telecom NZ Fibre Optic Cable Emplacement. -

Barriers to Fish Passage in the Waitakere Ranges and Muriwai Regional Parks : a Comprehensive Survey May 2005 TP 265

Barriers to fish passage in the Waitakere Ranges and Muriwai Regional Parks : a comprehensive survey May 2005 TP 265 Auckland Regional Council Technical Publication No. 265, May 2005 ISSN 1175 205X ISBN 1-877-353-83-3 www.arc.govt.nz Barriers to Fish Passage in the Waitakere Ranges and Muriwai Regional Parks: a comprehensive survey Prepared by: Grant E Barnes ARC Technical Publication 265 (TP 265) Auckland Regional Council Auckland May 2005 Acknowledgments The author wishes to thank Auckland Regional Council technical staff for their assistance with data collection; thanks to Colin McCready, Mike McMurtry and Joanne Wilks. Thanks to David Speirs, Environment Waikato, for his assistance with study design and assessment criteria and to Neil Dingle, Auckland Regional Council, for the development of the electronic field sheets. Permission to access the study sites was obtained from Watercare Service Ltd and the Auckland Regional Council. Contents Executive Summary i 1 Introduction and Rationale 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Study scope 2 2 Study sites 3 2.1 Waitakere Ranges Regional Park 3 2.2 Muriwai Regional Park 5 3 Methods 7 3.1 Structure Evaluation 7 3.2 Electronic Data Capture 8 3.3 Data Analysis 8 4 Results 9 4.1 Waitakere Ranges Water Supply Catchments 10 4.2 Other Waitakere Ranges Regional Park Sites 13 4.3 Muriwai Regional Park 13 5 Discussion 15 5.1 Legislative Obligations 17 5.2 Prioritisation of Fish Passage Restoration 17 6 Conclusion 19 References 21 Appendix 1: In-Stream Structure Record Sheet 23 Executive Summary A high proportion of New Zealand’s indigenous fish fauna are diadromous, requiring access between riverine habitat and marine or lake environments. -

AEBR 114 Review of Factors Affecting the Abundance of Toheroa Paphies

Review of factors affecting the abundance of toheroa (Paphies ventricosa) New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 114 J.R. Williams, C. Sim-Smith, C. Paterson. ISSN 1179-6480 (online) ISBN 978-0-478-41468-4 (online) June 2013 Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries websites at: http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-resources/publications.aspx http://fs.fish.govt.nz go to Document library/Research reports © Crown Copyright - Ministry for Primary Industries TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 2 2. METHODS ....................................................................................................................... 3 3. TIME SERIES OF ABUNDANCE .................................................................................. 3 3.1 Northland region beaches .......................................................................................... 3 3.2 Wellington region beaches ........................................................................................ 4 3.3 Southland region beaches ......................................................................................... -

Trade and Industry Momori Point GR 3976

3246 NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 141 Orpheus Point GR 5164. Adjacent to Orpheus Bay. Wigmore Bay GR 3976. Bay south of Te Henga locality. Pikaroro Point GR 5263. North side Manukau Entrance. Wing Head GR 4461. Bay south of Whatipu locality. Swanson Bay GR 5467. Bay north of Lawry Point. Wonga Wonga Bay GR 4460. Bay northern side of Manukau Symonds Bay GR 5468. Bay east of Parau locality. Entrance. Torea Bay GR 5363. North side of Manukau Entrance. Holder Lookout GR 7880. Lookout end of Glendowie Road, north of Orohe Point. North Auckland Land District Infomap 260 Qll Gisborne Land District Kitakita Falls GR 4370. Falls on Glen Esk Stream, SE of Piha. Pataua Island NZMS 1 N78 GR 1557. South-eastern arm, Glen Esk Stream GR 4271. Tributary of Piha Stream. Pataua (Trig) Ohiwa Harbour (spelling change from Kauwahaia Island GR 3878. Small island in O'Neill Bay. { Patawa). Lake Kawaupaka GR 4077. Small lake inland from Te Henga. Marawhara Stream GR 4172. Stream north of Piha. Canterbury Land District Ohaka Head GR 4263. High headland south of Pararaha Point. Te Wharau Stream Infomap 260 M36 GR 8528. Stream Panatahi Island GR 4166. Small island off Karekau Point. flowing through Orton Bradley Park to Paratutae Island GR 4460. Spelling error. Small island Charteris Bay. Manukau Entrance. Loch Cameron NZMSl SlO0 GR 7371. Castle Stream GR 4770. Correction from Snowys Stream. Lake Merino NZMSl Sl00 GR 7372. Stream north end Huia Reservoir. Twin Lakes NZMSl Sl00 GR 7471. Snowys Stream GR 4670. Stream NW end of Huia Lake Wardell NZMSl Sl00 GR 7974. -

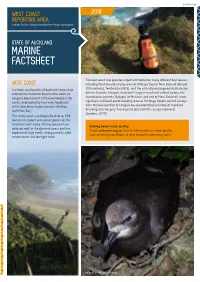

WEST COAST 2018 REPORTING AREA Includes Franklin, Rodney and Waitākere Ranges Local Boards

20-PRO-0199 WEST COAST 2018 REPORTING AREA Includes Franklin, Rodney and Waitākere Ranges local boards STATE OF AUCKLAND MARINE FACTSHEET The west coast also provides important habitat for many different bird species; WEST COAST including the dune and swamp areas of Whātipu Bay for New Zealand dotterel The black sand beaches of Auckland’s west coast (tūturiwhatu), fernbird (mātātā), and the critically endangered Australasian extend from Karioitahi Beach in the south, to bittern (matuku hūrepo), Auckland’s largest mainland seabird colony, the Rangitira Beach (north of Muriwai Beach) in the Australasian gannets (tākapu) at Muriwai, and one of New Zealand’s most north, interrupted by the rocky headlands significant mainland petrel breeding areas at Te Henga. Recent council surveys of the Waitākere Ranges between Whātipu from Muriwai south to Te Henga have also identified a number of mainland and Māori Bay. breeding sites for grey-faced petrel (ōi) and little penguin (korora) (Landers, 2017). The rocky coast is ecologically diverse, 598 documented plant and animal species on the intertidal reefs alone. Marine species have Bathing beach water quality: adapted well to the dynamic coast and the Check safeswim.org.nz for live information on water quality exposure of large swells, strong currents, cold and swimming conditions at your favourite swimming spots. temperatures and low light levels. Grey faced petrel, James Russell. WEST COAST BEACH PROFILING Beach profile (cross-shore change) monitoring is At southern Muriwai, following dune reshaping works undertaken at Piha and Muriwai beaches. Surveying in 2009 and 2016/2017, sand levels have remained high at northern Piha where the Wekatahi and Marawhara and have maintained a healthy shape despite significant streams run into the ocean has been carried out winter storms. -

Go West... Western Sector Regional Parks

18-PRO-0096 Go west... Western sector regional parks Waitākere Ranges Regional Park (Arataki, Huia, Cascade Kauri and Piha depots) • Muriwai Regional Park • Te Rau Puriri Regional Park Western parks at a glance... Being a student ranger in the west Most Aucklanders know the Waitākere Ranges, but not everyone Our students will take part in a five-day induction and will be knows that more than 16,500 hectares of the ranges is regional mentored by a ranger ‘buddy’ from the depot or location where they parkland with 240km of walking and tramping tracks. From the are based. Students will be assigned to Arataki but will be working gateway to the ranges, the Arataki Visitor Centre, over 155,000 across the western regional parks. One student will also be assigned people each year learn about the history of the ranges and get to the Arataki Visitor Centre but will also work in the field with other valuable advice on how to explore the parkland. students. The park has four lodges and four bookable baches, a scientific reserve You will meet the sector student liaison rangers and interact with at Whatipū, historic buildings, monuments and sites, including the duty rangers on a daily basis for work programmes and essential tasks. site of New Zealand’s worst maritime disaster in 1869 when 189 people perished in the wreck of the Orpheus. Tasks will range from visitor patrols, managing volunteer groups, nursery work, track maintenance, weed and pest control to farm work, Around 10,000 school kids take part in education programmes at amenity garden maintenance, sign and barrier maintenance, fencing Arataki each year. -

Hillary Trail Waitakere Ranges Regional Park

Hillary Trail Waitakere Ranges Regional Park 09 366 2000 www.arc.govt.nz 1 Introduction The Hillary Trail is a spectacular multi-day The trail was developed through the joint effort of the elected members, rangers and officers of tramping trip through native forest and along the Auckland Regional Council between 2005 and 2009. The ARC sees the creation of the the wild coast of the Waitakere Ranges Hillary Trail as an important legacy for the people Regional Park. Beginning and ending not of Auckland and New Zealand. far from metropolitan Auckland, this self- The ARC thanks the Hillary family for the use of guided 70km trail is a challenging wilderness Sir Edmund Hillary’s name. adventure designed to introduce families and young people, properly prepared, to the joys The Hillary connection The Hillary family has links of multi-day tramping. with the Waitakere Ranges going back to 1925, when The ranges are alive with history and the trail Sir Edmund’s father-in-law, Jim Rose, built a bach at links heritage areas connected with Te Kawerau Anawhata. Since then, five a Maki and the decades of kauri logging. It generations have come to passes through a wide range of environments – the west coast to walk and regenerating rainforest, stands of mature kauri, explore, to dream and to coastal forest, rocky shores and black-sand refresh their spirits. In 1981 beaches. And it seems as if around every corner Jim Rose wrote, ‘My family there is another magnificent view. look forward to the time when we will be able to walk from The inspiration behind the trail is New Zealand’s Huia to Muriwai on public great mountaineer, explorer and loved citizen, Sir walking tracks like the old time Edmund Hillary, who came to the rugged hills Maori could do.’ With the Hillary and beaches of the Waitakere Ranges to plan and Trail it is possible to do just that. -

West Coast Beaches West Including Muriwai, Bethells Beach, Anawhata, Piha and Karekare

West Coast Beaches West including Muriwai, Bethells Beach, Anawhata, Piha and Karekare uckland’s west coast is all deserted black sand beaches, crashing surf and steep bush- Aclad hillsides. This is a place for contemplation, rejuvenation and inspiration. Its soulful, severe beauty attracts artists, potters and art directors from Auckland’s adland. Karekare was the sullen, windswept backdrop for the 1993 movie The Piano and Xena has had many a sword and sandals moment here. It’s an environmentally sensitive area, with advocates constantly lobbying for the protection of the easily-trampled dunes in Piha, the coastline, native bush and rainforest. Piha is the most exclusive of the neighbourhoods and the only one with a road running alongside the beach. Muriwai appeals mainly because of its relative accessibility to Auckland. For others the stark, mystical remoteness of Bethells Beach, Anawhata and Karekare is a bonus, not a drawback. Population Profile Population 7,170 Muriwai % Aged Under 15 Years 23.43 % Aged Over 65 Years 5.61 Waitakere % European 78.58 % Maori 9.08 Swanson % Pacific Peoples 2.55 Bethells Beach % Asian 1.97 Te Henga Waitakere Reservoir Who Lives There? Anawhata i The West Coast beaches are not for the faint Waiatarua hearted – the drive to Piha alone needs to be undertaken with respect for the terrain, Piha and a good gearbox. It’s also not the place for Huia Reservoir faux lifestylers who think they can transplant Karekare their city designs on the landscape. As one real estate agent put so eloquently: “Start talking like that at a party out here and the music would stop all on its own.” An increasing number of city-siders are Whatipu choosing to relocate here and commute, Digital mapping data derived from Department of Survey. -

Intertidal Life Around the Waitakere Ranges

Intertidal Life Around the Coast of the Waitakere Ranges, Auckland January 2004 Technical Publication 298 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Auckland Regional Council Auckland Regional Council Technical Publication No. 298, January 2004 ISSN 1175–205X ISBN 1–877353–14–0 Printed on recycled paper www.arc.govt.nz i ii INTERTIDAL LIFE AROUND THE COAST OF THE WAITAKERE RANGES, AUCKLAND by Bruce W. Hayward1 and Margaret S. Morley2 1c/o Geomarine Research, 40 Swainston Rd, St Johns, Auckland 2c/o Auckland War Memorial Museum Prepared for Auckland Regional Council 2002 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Auckland Regional Council iii iv Foreword: Why is Auckland Regional Council publishing this Report? The Auckland Regional Council was given the opportunity to publish this report on the intertidal plants and animals of the Waitakere Ranges Coast by Bruce Hayward and Margaret Morley. The report is the result of a considerable amount of effort on the part of the authors and a wider group of participants and contributors during field-work, taxonomic identification, analysis and presentation of the information. The report presents the findings of this body of work accompanied by comprehensive species and habitat lists, coupled with an extensive array of handsome figures, illustrations and maps. The Council considers that the report provides a valuable information resource for those interested in Auckland's coastal ecology and biodiversity. The Council greatly appreciated the opportunity to make this valuable body of work available to the community through contribution of only the comparatively minor costs of formatting and printing. -

Waitakere Track Plan 6-6-19

Muriwai Regional Park Waitākere Ranges Track plan Key Open Rd Track in upcoming work programme hells Bet Pae O Te Rangi Long Road Farm Track Track not currently included in upcoming work programme Pae O Te Rangi Farm Te Henga Summit Track Walkway Whatatiri Track Bethells Auckland Road Lake Wainamu City Walk Track Lake Wainamu Long Road Te Henga Track Upper Kauri Waitakere Opanuku Pipeline Dam Walk Track Houghton Track Track Fence Line Spragg’s e Track v i Long Road r Bush D Track Waitākere Track c i Reservoir n e c S Kuataika Track Fairy Falls Track Anawhata Large Kauri Anawhata Beach Track Anawhata Farm Walk Loop Track Cutty Grass New Track Track Fishermans Rock Track Rose Track Anawhata Ian Wells Track Arataki Visitor Road Centre Laird ThomsonTrack Anawhata Arataki Arataki R White Track o Upper Nihotupu Nature Trail Nature Trail Marawhara Walk a e d Lower Loop Upper Loop Walk iv McElwain r D Maungaroa iha Ro Parker Track ic Lookout P ad en Lookout Track c Track Beveridge S Exhibition North Piha Road Upper Nihotupu Track Upper Dam Road Arataki Lookout Track Drive Nihotupu Seaview Slip Track Piha Road Reservoir Zigzag Byers Walk Track Lion Rock Track Glen Kitekite Track Esk Road Connect Track Pipeline Road Tasman Lookout Track Kauri Grove Track Lower Nihotupu Upper Huia Reservoir New Knutzen Reservoir Lower Nihotupu Dam Road Taitomo Track Track Te Āhuahu Road Winstone Track Log Race Road Parau Track Ussher Track Mercer Bay Piha Road Loop Track Huia Dam Road Comans Track d Lower Huia R e Reservoir Panto Track r a k d Ahu Ahu Track e a -

General SA2 Level 2018 Census Results (Charles Crothers, AUT)

General SA2 Level 2018 Census results (Charles Crothers, AUT) Pop 2013_2018 15_29_years_201 30_64_years_201 65_years_and_ov occupied pvt dwel unoccupied pvt SA2namet TA name Pop_Total_2018 percentChange 8 % 8 % er_2018 % 2018 dwel 2018 North Cape Far North District 1602.00 16.80 14.23 44.94 21.16 633 219 Rangaunu Far North District 2310.00 13.90 16.88 42.47 15.84 777 174 Harbour Inlets Far North Far North District 45.00 -28.60 6.67 60.00 33.33 75 3 District Karikari Peninsula Far North District 1251.00 7.50 9.83 46.28 25.90 483 657 Tangonge Far North District 1134.00 .30 15.34 45.77 16.40 393 66 Ahipara Far North District 1230.00 19.20 16.59 45.85 15.85 396 153 Kaitaia East Far North District 2388.00 20.40 20.85 38.57 13.44 768 87 Kaitaia West Far North District 3483.00 19.90 19.55 36.61 16.88 1119 105 Rangitihi Far North District 936.00 14.30 17.95 44.55 16.67 333 33 Oruru-Parapara Far North District 846.00 23.10 14.89 49.65 15.96 288 90 Taumarumaru Far North District 2193.00 21.00 11.08 40.90 31.60 882 516 Herekino-Takahue Far North District 963.00 3.90 14.64 44.86 17.13 330 105 Peria Far North District 1107.00 16.40 14.36 48.78 15.99 426 90 Taemaro-Oruaiti Far North District 867.00 30.20 13.49 49.13 19.38 282 243 Whakapaku Far North District 744.00 5.10 10.89 45.97 22.18 276 234 Hokianga North Far North District 795.00 6.90 15.09 39.25 20.00 297 114 Kohukohu- Far North District 726.00 16.30 11.57 46.28 23.14 285 81 Broadwood Whakarara Far North District 1344.00 31.00 15.40 43.75 20.31 480 231 Kaeo Far North District 1191.00 18.50 16.12 -

17990 Rongoā Selection & Engagement Framework

17990 RONGOĀ SELECTION & ENGAGEMENT FRAMEWORK JUNE 2018 Chris Pairama Director - Project Manager Kaipara Rohe – Te Whiti te Rā o Rēweti Marae Wānanga 2 1105 State Highway 16 Waimauku Auckland 0883 0210400072 [email protected] E NGA MATE HAERE. E MOKIMOKI ANA MATOU KAPUA POURI I TENEI WA. HAERE NGA MATE. RERE ATU I RUNGA I TE MATIMATI O TE TUPUNA MANU O WAITEMATA. TENEI TE TANGI I A MATOU NGA URI O TE MAUNGA TAPU TAUWHARE ME TE TUPUNA MANU KAIPARA. KA AO KA AO KA AWATEA Chris Pairama / Te MAMAI O KAURI pilot project report #2 / 2 TE MAMAI O KAURI PILOT PROJECT REPORT #2 by Chris Pairama (Te Taoū, Ngāti Whātua) Chris Pairama / Te MAMAI O KAURI pilot project report #2 / 3 Te Uhi Table of Contents Te MAMAI O KAURI pilot project report #2................................................................................ 2 Wānanga Report.............................................................................................................................. 4 Kupu Whakataki / Introduction .................................................................................................... 10 Terms of the Work Authorisation ............................................................................................. 10 Project Objectives ..................................................................................................................... 10 MPI Terms of Procurement ...................................................................................................... 11 Kupu Whakamārama ...................................................................................................................