Tracking Down South Branch House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution Fidler in Context

TABLE OF CONTENTS acknowledgements vii introduction Fidler in Context 1 first journal From York Factory to Buckingham House 43 second journal From Buckingham House to the Rocky Mountains 95 notes to the first journal 151 notes to the second journal 241 sources and references 321 index 351 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION FIDLER IN CONTEXT In July 1792 Peter Fidler, a young surveyor for the Hudson’s Bay Company, set out from York Factory to the company’s new outpost high on the North Saskatchewan River. He spent the winter of 1792‐93 with a group of Piikani hunting buffalo in the foothills SW of Calgary. These were remarkable journeys. The river brigade travelled more than 2000 km in 80 days, hauling heavy loads, moving upstream almost all the way. With the Piikani, Fidler witnessed hunts at sites that archaeologists have since studied intensively. On both trips his assignment was to map the fur-trade route from Hudson Bay to the Rocky Mountains. Fidler kept two journals, one for the river trip and one for his circuit with the Piikani. The freshness and immediacy of these journals are a great part of their appeal. They are filled with descriptions of regional landscapes, hunting and trading, Native and fur-trade cultures, all of them reflecting a young man’s sense of adventure as he crossed the continent. But there is noth- ing naive or spontaneous about these remarks. The journals are transcripts of his route survey, the first stages of a map to be sent to the company’s head office in London. -

The Archaeology of Brabant Lake

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF BRABANT LAKE A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sandra Pearl Pentney Fall 2002 © Copyright Sandra Pearl Pentney All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, In their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (S7N 5B 1) ABSTRACT Boreal forest archaeology is costly and difficult because of rugged terrain, the remote nature of much of the boreal areas, and the large expanses of muskeg. -

An Indian Chief, an English Tourist, a Doctor, a Reverend, and a Member of Ppparliament: the Journeys of Pasqua’S’S’S Pictographs and the Meaning of Treaty Four

The Journeys of Pasqua’s Pictographs 109 AN INDIAN CHIEF, AN ENGLISH TOURIST, A DOCTOR, A REVEREND, AND A MEMBER OF PPPARLIAMENT: THE JOURNEYS OF PASQUA’S’S’S PICTOGRAPHS AND THE MEANING OF TREATY FOUR Bob Beal 7204 76 Street Edmonton, Alberta Canada, T6C 2J5 [email protected] Abstract / Résumé Indian treaties of western Canada are contentious among historians, First Nations, governments, and courts. The contemporary written docu- mentation about them has come from one side of the treaty process. Historians add information from such disciplines as First Nations Tradi- tional Knowledge and Oral History to draw as complete a picture as possible. Now, we have an additional source of written contemporary information, Chief Pasqua’s recently rediscovered pictographs showing the nature of Treaty Four and its initial implementation. Pasqua’s ac- count, as contextualized here, adds significantly to our knowledge of the western numbered treaty process. The pictographs give voice to Chief Pasqua’s knowledge. Les traités conclus avec les Indiens de l’Ouest canadien demeurent liti- gieux pour les historiens, les Premières nations, les gouvernements et les tribunaux. Les documents contemporains qui discutent des traités ne proviennent que d’une seule vision du processus des traités. Les historiens ajoutent des renseignements provenant de disciplines telles que les connaissances traditionnelles et l’histoire orale des Autochto- nes. Ils bénéficient désormais d’une nouvelle source écrite contempo- raine, les pictogrammes récemment redécouverts du chef Pasqua, qui illustrent la nature du Traité n° 4 et les débuts de son application. Le compte rendu du chef, tel que replacé dans son contexte, est un ajout important à notre connaissance du processus des traités numérotés dans l’Ouest canadien. -

Lt. Aemilius Simpson's Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society August 2014 Lt. Aemilius Simpson’s Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826 Edited by William Barr1 and Larry Green CONTENTS PREFACE The journal 2 Editorial practices 3 INTRODUCTION The man, the project, its background and its implementation 4 JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE ACROSS THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA IN 1826 York Factory to Norway House 11 Norway House to Carlton House 19 Carlton House to Fort Edmonton 27 Fort Edmonton to Boat Encampment, Columbia River 42 Boat Encampment to Fort Vancouver 62 AFTERWORD Aemilius Simpson and the Northwest coast 1826–1831 81 APPENDIX I Biographical sketches 90 APPENDIX II Table of distances in statute miles from York Factory 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. 1. George Simpson, 1857 3 Fig. 2. York Factory 1853 4 Fig. 3. Artist’s impression of George Simpson, approaching a post in his personal North canoe 5 Fig. 4. Fort Vancouver ca.1854 78 LIST OF MAPS Map 1. York Factory to the Forks of the Saskatchewan River 7 Map 2. Carlton House to Boat Encampment 27 Map 3. Jasper to Fort Vancouver 65 1 Senior Research Associate, Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary, Calgary AB T2N 1N4 Canada. 2 PREFACE The Journal The journal presented here2 is transcribed from the original manuscript written in Aemilius Simpson’s hand. It is fifty folios in length in a bound volume of ninety folios, the final forty folios being blank. Each page measures 12.8 inches by seven inches and is lined with thirty- five faint, horizontal blue-grey lines. -

University of Alberta Perceptions and Parameters of Education As A

University of Alberta Perceptions and Parameters of Education as a Treaty Right within the Context of Treaty 7 Sheila Carr-Stewart A thesis submitted to the Faculîy of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Administration and Leadership Department of Educational Policy Studies Edmonton, Alberta spring 2001 National Library Bibliothèque nationale m*u ofCanada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographk Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Oîîawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenirise de celle-ci ne doivent êeimprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation . In memory of John and Betty Carr and Pat and MyrtIe Stewart Abstract On September 22, 1877, representatives of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Tsuu T'ha and Stoney Nations, and Her Majesty's Govemment signed Treaty 7. Over the next century, Canada provided educational services based on the Constitution Act, Section 91(24). -

In Saskatchewan

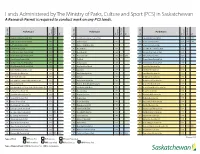

Lands Administered by The Ministry of Parks, Culture and Sport (PCS) in Saskatchewan A Research Permit is required to conduct work on any PCS lands. Park Name Park Name Park Name Type of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year HP Cannington Manor Provincial Park 1986 NE Saskatchewan Landing Provincial Park 1973 RP Crooked Lake Provincial Park 1986 PAA 2018 HP Cumberland House Provincial Park 1986 PR Anderson Island 1975 RP Danielson Provincial Park 1971 PAA 2018 HP Fort Carlton Provincial Park 1986 PR Bakken - Wright Bison Drive 1974 RP Echo Valley Provincial Park 1960 HP Fort Pitt Provincial Park 1986 PR Besant Midden 1974 RP Great Blue Heron Provincial Park 2013 HP Last Mountain House Provincial Park 1986 PR Brockelbank Hill 1992 RP Katepwa Point Provincial Park 1931 HP St. Victor Petroglyphs Provincial Park 1986 PR Christopher Lake 2000 PAA 2018 RP Pike Lake Provincial Park 1960 HP Steele Narrows Provincial Park 1986 PR Fort Black 1974 RP Rowan’s Ravine Provincial Park 1960 HP Touchwood Hills Post Provincial Park 1986 PR Fort Livingstone 1986 RP The Battlefords Provincial Park 1960 HP Wood Mountain Post Provincial Park 1986 PR Glen Ewen Burial Mound 1974 RS Amisk Lake Recreation Site 1986 HS Buffalo Rubbing Stone Historic Site 1986 PR Grasslands 1994 RS Arm River Recreation Site 1966 HS Chimney Coulee Historic Site 1986 PR Gray Archaeological Site 1986 RS Armit River Recreation Site 1986 HS Fort Pelly #1 Historic Site 1986 PR Gull Lake 1974 RS Beatty -

October 16, 2006 Province Officially Opens Anthony Henday Drive Southwest to 30,000 Daily Motorists First Completed Ring Road Se

October 16, 2006 Province officially opens Anthony Henday Drive Southwest to 30,000 daily motorists First completed ring road section in Alberta opens to traffic Edmonton...Motorists travelling between Highway 2 and Highway 16 around Edmonton have a new, more efficient travelling option, as the province officially opened the final eight-kilometre section of the Anthony Henday Drive Southwest Ring Road. Minister of Infrastructure and Transportation Ty Lund, joined by Edmonton Mayor Stephen Mandel, marked the official opening of the first complete leg of a ring road in Alberta. "The completion of the southwest ring road supports the ongoing growth of the Capital Region and creates a new and vital economic link within the province," said Lund. "Investing in Alberta's highway network, and in ring road infrastructure, supports the province's strong economy and contributes to Alberta's future growth." The provincial cost for completing the 18-kilometre southwest section of the Anthony Henday Drive was $310 million and includes five interchanges (Calgary Trail/Gateway Boulevard, Terwillegar Drive, 111 Street, Whitemud Drive, and 87 Avenue), three ravine crossings (Blackmud, Whitemud, and Wedgewood), and twin bridges over the North Saskatchewan River. "One of the City of Edmonton's key priorities is the swift completion of Anthony Henday Drive, and the opening and the southwest ring road is another important step toward realizing this goal," said Mayor Stephen Mandel. "The City is proud to work with the Government of Alberta on this project, as it both reinforces Edmonton's position as the service hub for northern development and meets the transportation needs of our citizens and the entire capital region." The expected traffic volume on Anthony Henday Drive Southwest is approximately 30,000 vehicles per day. -

News Release

News release July 16, 2012 Construction digs-in on final leg of Edmonton ring road Final leg of Anthony Henday Drive set to open to traffic in 2016 Edmonton ... The finish line on the Edmonton ring road is in sight with the final northeast leg of the Anthony Henday Drive scheduled to open in fall 2016. “It is very rewarding to turn sod on a project that is so far reaching. This new road improves our quality of life, supports a changing and expanding population and furthers Alberta’s economic growth,” said Minister of Transportation Ric McIver. “This is an exciting step in moving toward the long-range vision of the Edmonton Ring Road that began in the 1970s.” More than 50,000 Albertans use the Henday each day. The ring road, once completed, will change the way residents in the Capital Region connect with the people and services that matter to them – reducing commute times and traffic congestion. It will also dramatically benefit industry that uses the freeway as a vital route in all four directions, getting our products to market more quickly and efficiently. The Alberta government signed a 34-year contract with the Capital City Link General Partnership to design, build, operate, and partially finance Northeast Anthony Henday Drive. The public-private partnership (P3) contract is worth $1.81 billion in 2012 dollars, to be paid over the term of the contract, and follows a P3 selection process which began in March 2011. This is a savings of $370 million, compared to the estimated cost of $2.18 billion using traditional delivery. -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

Britain and the Fur Trade: Commerce and Consumers in the North-Atlantic World, 1783-1821

Citation: Hope, David (2016) Britain and the Fur Trade: Commerce and Consumers in the North-Atlantic World, 1783-1821. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/31598/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html Britain and the Fur Trade: Commerce and Consumers in the North-Atlantic World, 1783-1821 David Hope PhD 2016 Britain and the Fur Trade: Commerce and Consumers in the North-Atlantic World, 1783-1821 David Hope A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences September 2016 Abstract This is a study of the mercantile organisation of the British fur trade in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. -

Memoir-Sneak-Peek-For-Website1.Pdf

The Hargrave Ranch: Five Generations of Change (1888 – 2013) 1 Lorna Michael Butler2 3 The story of the Hargrave Ranch, Walsh, Alberta, as portrayed in 2013, blends the backgrounds and contributions of five unique generations. While this synopsis cannot begin to do justice to the contributions and experiences of each generation, it is an attempt to paint a brief picture of the roles that each generation played in shaping the Hargrave Ranch over 125 years. In retrospect, there have been many key individuals, both women and men, who have played important roles, and not all were family members. It is apparent that it takes a dedicated team to develop and operate a southern Alberta cattle ranch for 125 years. Each generation has made unique contributions, and has faced challenges that could not have been predicted. But the JH ranch and the natural resources that are key to its resilience have been husbanded in keeping with the best knowledge and technology that was available at the time. Five generation of Hargraves, and their families, neighbors and friends must be credited with making the JH Ranch the special place that it is today. The story that follows is intended to highlight the ranching business itself, however, the story cannot be told without glimpses of the lives of the people who have been involved. 1. The Founding Family and First Generation: James (‘Jimmy’) Hargrave and Alexandra “Lexie’ Helen Sissons The Ancestors of James Hargrave James Hargrave (1846-1935) was born in Beech Ridge (one source refers to his birthplace as Chataugee), Quebec (50 mi. -

Treaty Boundaries Map for Saskatchewan

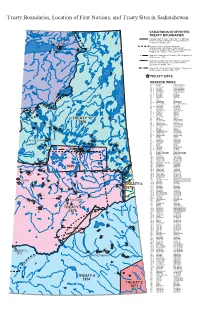

Treaty Boundaries, Location of First Nations, and Treaty Sites in Saskatchewan VARIATIONS IN DEPICTED TREATY BOUNDARIES Canada Indian Treaties. Wall map. The National Atlas of Canada, 5th Edition. Energy, Mines and 229 Fond du Lac Resources Canada, 1991. 227 General Location of Indian Reserves, 225 226 Saskatchewan. Wall Map. Prepared for the 233 228 Department of Indian and Northern Affairs by Prairie 231 224 Mapping Ltd., Regina. 1978, updated 1981. 232 Map of the Dominion of Canada, 1908. Department of the Interior, 1908. Map Shewing Mounted Police Stations...during the Year 1888 also Boundaries of Indian Treaties... Dominion of Canada, 1888. Map of Part of the North West Territory. Department of the Interior, 31st December, 1877. 220 TREATY SITES RESERVE INDEX NO. NAME FIRST NATION 20 Cumberland Cumberland House 20 A Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 B Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 C Muskeg River Cumberland House 20 D Budd's Point Cumberland House 192G 27 A Carrot River The Pas 28 A Shoal Lake Shoal Lake 29 Red Earth Red Earth 29 A Carrot River Red Earth 64 Cote Cote 65 The Key Key 66 Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 66 A Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 68 Pheasant Rump Pheasant Rump Nakota 69 Ocean Man Ocean Man 69 A-I Ocean Man Ocean Man 70 White Bear White Bear 71 Ochapowace Ochapowace 222 72 Kahkewistahaw Kahkewistahaw 73 Cowessess Cowessess 74 B Little Bone Sakimay 74 Sakimay Sakimay 74 A Shesheep Sakimay 221 193B 74 C Minoahchak Sakimay 200 75 Piapot Piapot TREATY 10 76 Assiniboine Carry the Kettle 78 Standing Buffalo Standing Buffalo 79 Pasqua