For Peer Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checking out on Plastics, EIA and Greenpeace

Checking out on plastics A survey of UK supermarkets’ plastic habits ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABOUT EIA ABOUT GREENPEACE CONTENTS We investigate and campaign against Greenpeace defends the natural We would like to thank The Network ©EIAimage 1. Executive summary 4 environmental crime and abuse. world and promotes peace by for Social Change, Susie Hewson- investigating, exposing and Lowe and Julia Davies. Our undercover investigations 2. Introduction 5 confronting environmental abuse expose transnational wildlife crime, We would would also like like to to thank thank our ABOUT EIA EIAand championingUK responsible with a focus on elephants, pangolins 3. Impacts of plastics on the environment and society 6 numerous other supporters whose 62-63solutions Upper for Street, our fragile Ximporae. Ut aut fugitis resti ut atia andWe investigate tigers, and and forest campaign crimes suchagainst long-term commitment to our Londonenvironment. N1 0NY UK nobit ium alici bla cone consequam asenvironmental illegal logging crime and and deforestation abuse. 4. Methodology 8 organisation’s mission and values T: +44 (0) 20 7354 7960 cus aci oditaquates dolorem volla for cash crops like palm oil. We helped make this work possible. Our undercover investigations E: [email protected] vendam, consequo molor sin net work to safeguard global marine Greenpeace, Canonbury Villas, London N1 5. Results of scorecard ranking 9 expose transnational wildlife crime, eia-international.org fugitatur, qui int que nihic tem ecosystems by addressing the 2PN, UK with a focus on elephants and asped quei oditaquates dolorem threats posed by plastic pollution, T: + 44 (0) 20 7865 8100 6. Summary of survey responses tigers, and forest crimes such as volla vendam, conseqci oditaquates bycatch and commercial EIAE: [email protected] US illegal logging and deforestation for dolorem volla vendam, consequo exploitation of whales, dolphins POgreenpeace.org.uk Box 53343 6.1 Single-use plastic packaging 10 cash crops like palm oil. -

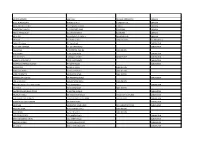

National Retailers.Xlsx

THE NATIONAL / SUNDAY NATIONAL RETAILERS Store Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Post Code M&S ABERDEEN E51 2-28 ST. NICHOLAS STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1BU WHS ST NICHOLAS E48 UNIT E5, ST. NICHOLAS CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW SAINSBURYS E55 UNIT 1 ST NICHOLAS CEN SHOPPING CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW RSMCCOLL130UNIONE53 130 UNION STREET ABERDEEN, GRAMPIAN AB10 1JJ COOP 204UNION E54 204 UNION STREET X ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY CONV E54 SOFA WORKSHOP 206 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY ALF PL E54 492-494 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1TJ TESCO DYCE EXP E44 35 VICTORIA STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1UU TESCO HOLBURN ST E54 207 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BL THISTLE NEWS E54 32 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BT J&C LYNCH E54 66 BROOMHILL ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6HT COOP GT WEST RD E46 485 GREAT WESTERN ROAD X ABERDEEN AB10 6NN TESCO GT WEST RD E46 571 GREAT WESTERN ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6PA CJ LANG ST SWITIN E53 43 ST. SWITHIN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6XL GARTHDEE STORE 19-25 RAMSAY CRESCENT GARTHDEE ABERDEEN AB10 7BL SAINSBURY PFS E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA ASDA BRIDGE OF DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA SAINSBURY G/DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA COSTCUTTER 37 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BN RS MCCOLL 17UNION E53 17 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BU ASDA ABERDEEN BEACH E55 UNIT 11 BEACH BOULEVARD RETAIL PARK LINKS ROAD, ABERDEEN AB11 5EJ M & S UNION SQUARE E51 UNION SQUARE 2&3 SOUTH TERRACE ABERDEEN AB11 5PF SUNNYS E55 36-40 MARKET STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5PL TESCO UNION ST E54 499-501 -

Survey of Retailers

1 1. Contents 1. Contents ............................................................................................................. 2 2. Executive summary .............................................................................................. 3 Background and methodology ..................................................................................... 3 Key findings ............................................................................................................. 3 3. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 5 Research objectives ................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 5 Sample .................................................................................................................... 5 Participation criteria .................................................................................................. 8 Fieldwork ................................................................................................................. 8 Presentation of results ............................................................................................... 9 Respondent profile .................................................................................................. 10 4. Supply arrangements and local competition ......................................................... -

Interplay of Socioeconomic Status and Supermarket Distance Is Associated with Excess Obesity Risk: a UK Cross‐Sectional Study

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, S1 of S2 Supplementary Materials: Interplay of Socioeconomic Status and Supermarket Distance Is Associated with Excess Obesity Risk: A UK Cross‐Sectional Study Thomas Burgoine, Joreintje D. Mackenbach, Jeroen Lakerveld, Nita G. Forouhi, Simon J. Griffin, Søren Brage, Nicholas J. Wareham and Pablo Monsivais Table S1. Details of the food outlet classification system used, according to primary retail function, with UK examples of chains and types (where applicable). This seven point food outlet classification system was derived from a more detailed 21‐point schema published by Lake et al (2010) [1]. Type of Outlet Common Defining Characteristics; Chain and Type Examples Food orders are taken by wait staff Food served to be consumed on the premises Food delivered to the table Restaurant Food paid for after eating Type: by cuisine, pizza, burger, fine dining; by origin, British, Chinese, Italian, Indian, American Chains: Pizza Express, Gourmet Burger Kitchen, Pizza Hut, Nando’s Sells limited range of groceries, newspapers/magazines, snacks, drinks, lottery, tobacco and alcohol products Convenience Often have extended opening hours store Usually small in size Type: convenience stores, newsagents, frozen, discount Chains: Londis, SPAR, Nisa, Premier Stores, Heron Foods, Poundland Departmentalised, self‐service mutiple chain store selling a wide range of groceries and household goods Supermarket Type: large, small Chains: Tesco, Sainsbury’s, ASDA, Morrisons, the Co‐operative, Waitrose, Aldi, -

Differences in Expenditure and Amounts of Fresh Foods, Fruits and Vegetables, and fish Purchased in Urban and Rural Scotland

Public Health Nutrition: 20(3), 524–533 doi:10.1017/S1368980016002688 Differences in expenditure and amounts of fresh foods, fruits and vegetables, and fish purchased in urban and rural Scotland Baukje de Roos*, Ferdinando Binacchi, Stephen Whybrow and Alan A Sneddon Rowett Institute of Nutrition & Health, University of Aberdeen, Foresterhill, Aberdeen AB25 2ZD, UK Submitted 5 April 2016: Final revision received 28 July 2016: Accepted 30 August 2016: First published online 5 October 2016 Abstract Objective: To quantitatively analyse expenditure on all fresh foods, fruits and vegetables (F&V) and fish across urban and rural households in Scotland. Fresh foods were chosen since, in general, they are perceived to contribute more to health than processed foods. Design: Descriptive analysis of purchase data of all foods brought into the home during 2012 from the Kantar Worldpanel database. Purchase data were restricted to fresh, unprocessed and raw foods or ‘fresh to frozen’ foods where freezing was part of harvesting. Total household purchases were adjusted for household size and composition. Setting: Scotland. Subjects: Households (n 2576). Results: Rural households reported the highest expenditure per person on fresh foods and F&V, but also bought the most (kilograms) of these items. There were linear trends of average prices paid with urban–rural location (P < 0·001), with average prices paid by large urban and remote rural households being £2·14/kg and £2·04/kg for fresh foods, £1·64/kg and £1·60/kg for F&V and £10·07/kg and £10·20/kg for fish, respectively, although differences were quantitatively small. -

Message to Shoppers

MESSAGE TO SHOPPERS We would like to assure shoppers that our members; your local convenience stores, are doing their best to keep products available to you at this extremely difficult time for everyone. Please be kind to them; they are doing their best and putting themselves on the front-line to help you – the consumer! Because our retailers are community based, not only may they be in a position to offer goods which you can no longer buy in the supermarkets; they may be able to help those who are most vulnerable but offering local deliveries. For those of you who aren’t sure of where your local store is, we’ve pulled together a list of these. Simply click on the store finder links below to help you source your nearest retailer: BEST ONE https://www.best-one.co.uk/store-locator CO-OP https://finder.coop.co.uk/food COSTCUTTER https://www.costcutter.co.uk/location-finder/ COSTCO https://www.costco.co.uk/store-finder DAY-TODAY https://www.day-today.co.uk/shops/ FAMILTY SHOPPER https://www.familyshopperstores.co.uk/our-stores FARMFOODS https://www.farmfoods.co.uk/store-finder.php GO LOCAL http://www.golocalextra.co.uk/ KEYSTORE https://www.keystore.co.uk/store-locator/ LIFESTYLE EXPRESS https://www.localstore.co.uk/stores/83092/lifestyle-express/ LONDIS https://www.londis.co.uk/our-stores MACE https://www.macestores.co.uk/ MORRISON’S https://my.morrisons.com/storefinder/ FORECOURTS MCCOLLS https://www.mccolls.co.uk/ MARGIOTTA http://www.margiotta.co.uk/contact NISA https://www.nisalocally.co.uk/ ONE STOP https://www.onestop.co.uk/ ONE-O-ONE http://one-o-one.co.uk/stores/ PREMIER https://www.premier-stores.co.uk/our-stores SCOTMID https://scotmid.coop/store-locator/ SPAR https://www.spar.co.uk/ U-SAVE http://www.usave.org.uk/locations/ . -

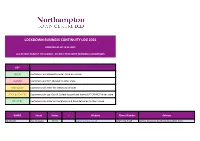

Lockdown Business Continuity Log 2021

LOCKDOWN BUSINESS CONTINUITY LOG 2021 UPDATED AS OF 15.01.2021 ALL DETAILS SUBJECT TO CHANGE - PLEASE CHECK WITH INDIVIDUAL BUSINESSES KEY OPEN Customers are allowed to enter store as normal CLOSED Customers are NOT allowed to enter store TAKEAWAY Customers can enter for takeaway services CLICK & COLLECT Customers can use Click & Collect to purchase items BUT CANNOT enter store DELIVERY Customers can order online/phone and have delivered to their house BANKS Street Status - Website Phone Number Address BARCLAYS The Drapery OPEN www.barclays.co.uk 0345 734 5345 18 The Drapery, Northampton, NN1 2HG COVENTRY BUILDING Abington Street OPEN www.coventrybuildingsociety.co.uk 01604 626372 10 Abington Street, Northampton, NN1 2AJ SOCIETY HALIFAX Market Square OPEN www.halifax.co.uk 0345 720 3040 17 Market Square, Northampton, NN1 2DW HSBC Abington Street OPEN www.hsbc.co.uk 03457 404 404 22 Abington St, Northampton NN1 2AJ LLOYDS BANK George Row OPEN www.lloydsbank.com 0345 602 1997 2 George Row, Northampton, NN1 1DJ METRO BANK Abington Street OPEN www.metrobankonline.co.uk 0203 402 8270 27-29 Abington Street, Northampton, NN1 2AN NATWEST The Drapery OPEN www.natwest.com 03457 888 444 41 The Drapery, Northampton, NN1 2EY NATIONWIDE Abington Street OPEN www.nationwide.co.uk 0800 554 0454 24 Abington Street, Northampton, NN1 2AJ BUILDING SOCIETY SKIPTON BUILDING Abington Street OPEN www.skipton.co.uk 01604 630105 2/2A Abington Street, Northampton, NN1 2AJ SOCIETY SANTANDER Market Square OPEN www.santander.co.uk 0800 9 123 123 1 Market Square, Northampton, -

Publishers Deny Broken Delivery Times Promises

03.04.2015 24HR SNACK SALES Six key daily opportunities CATEGORY GUIDE Page 32 » Big brands, great prices ‘We’re getting ready for Aldi’s arrival’ Page 28 » NEWS ● CONVENIENCE ● PROFIT www.betterretailing.com ● £2.20 Publishers deny broken delivery GOING DARK Trading times promises Standards: NFRN urges trade to meet after missed cut-off times jump 31%. Page 5 » We’ll police PARCELS ban with Click & tip-offs Collect Councils favour red tape collaboration over enforcement. Page 4 » removed Removing lockers DISPLAY BAN legislation opens market. Page 6 » Savvy suppliers LOTTERY seize ad Irish lotto openings nightmare Lyca Mobile offers Customers turned free shutters, away after terminal but retailers still waiting as deadline chaos. Page 14 » nears. Page 4 » Vol 126 No 14 Eat 17 your heart out FOR TRADE USE ONLY Some of the UK’s top independent retailers and their suppli- ers came together to celebrate the 2015 launch of the Independent Achievers Acad- Six experts’ advice 14 emy last week. Held at the trendy Spar Hackney store and Eat 17 restaurant, guests for keeping your store took up the chance to check out the store with owner James Brundle, pictured left. secure. Page 30 » Page 36 » “Our shoppers know they’re getting great value and it’s driving footfall in my store.” Steve Morris - ex Londis retailer FOOTFALL UP! SALES UP! PROFITS UP! Call us today on www.premier-stores.co.uk 01933 371757 63227 Retail Newsagents - Retailer Profile - 3rd April.indd 1 24/03/2015 14:43 Retail Newsagent 3 April 2015 3 In the book Winnie the Pooh, the characters are preparing for a trip to the North Pole when Pooh encounters Rabbit and asks: “Hello Rabbit, is that you?” Rabbit replies: “Let’s pretend it isn’t and see what happens.” More than A. -

Response to Request for Information

[NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED] Response to Request for Information Reference FOI 101587 Date 16 October 2015 Licensed Venues Request: Under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) we would like to request contact information for all Licensed Venues within your local authority. We would like an electronic copy only of this information, and would like the following included: Venue Name Address Owner name Landlord name Phone number Following reasonable enquiries, it has been established that the Council does not hold some of the above information. Consequently, we are unable to provide some of the information relating to the above, as per Section 1(1)(a) of the Act: "Any person making a request for information to a public authority is entitled to be informed in writing by the public authority whether it holds information of the description specified in the request". Additionl Description PLH Premises Address Post Code Bradmore Post Office & News Ravi Saini 17 Broad Lane WV3 9BN Sunridge News Ltd Sunridge News Ltd 34 Birchwood Road WV4 5UH Spice King Awlad Hussain 394 Penn Road WV4 4DF Sharma News Rajeev Kumar Sharma 130 Lime Street WV3 0EX Cosmo Midlands Investment Limited Unit B8 Bentley Bridge WV11 1UJ Heath Town Club Kirandeep Kaur Grewal Woden Road WV10 0AU Whetstone Green Convience Store Vinoshanth Alphonse Jayakumar 4a Whetstone Green WV10 9EZ Sing-Fellows Sing-fellows (Wton) Ltd 55-57 Lichfield Street WV1 1EQ 42/46 Mander Sq, Mander Discount UK PoundWorld Retail Limited Centre WV1 3NH Mr Sizzle Mr M A Smith, Mr SF Smith & Miss S L Smith -

Mr Richardson

MR RICHARDSON ASH VILLE NEVILLES CROSS BANK DURHAM D & C NEWSAGENTS 9 FRONT STREET SHERBURN HILL DURHAM BALIGANS OFF LICENCE 17 ST MARYS TERRACE COXHOE DURHAM ANDERSON'S BAKERY 5, CROWTREES LANE BOWBURN DURHAM PENNY PETROLEUM DALLYMORE DRIVE BOWBURN DURHAM MR KHAN 15 FREDERICK ST NORTH MEADOWFIELD DURHAM MR REAY 41 FRONT STREET LANGLEY PARK VIA WHSMITHS Lallys Off Licence 19, Yarm Road DARLINGTON B & G MINI MARKET 27 - 29 YARM ROAD DARLINGTON WHSMITHS 37 CORNMILL CENTRE DARLINGTON D & S NEWS 2, PREBEND ROAD DARLINGTON TESCO EXPRESS CORNMILL CENTRE MARKET WAY DARLINGTON MARKS & SPENCER PLC 70-76, NORTHGATE DARLINGTON MORRISONS PETROL STATION 97 NORTH ROAD DARLINGTON MORRISONS 97 NORTH ROAD DARLINGTON PARKGATE NEWS 117-119 PARKGATE DARLINGTON ASDA STORE 4796 HAUGHTON ROAD DARLINGTON THANDIS OFF LICENCE 64, FREEMANS PLACE DARLINGTON ONE STOP SHOP 218-220 YARM ROAD DARLINGTON B&N OFF LICENCE & CONVENIENCE 172, YARM ROAD DARLINGTON MC COLLS 364A YARM ROAD DARLINGTON SALTERS CONVENIENCE STORE 1, SALTERS AVENUE DARLINGTON PREMIER STORES 49, HAUGHTON GREEN HAUGHTON LE SKERNE DARLINGTON ALDI (STORE 105 DTON 2) 5 NORTH ROAD RETAIL PARK NORTH ROAD DARLINGTON NORTH ROAD MINI MARKET 88, NORTH ROAD DARLINGTON MR SINGH HAUGHTON ROAD NEWS 220 HAUGHTON ROAD DARLINGTON PHOENIX STORE 45-47 BARTON STREET DARLINGTON RANA NEWS 65 ALLEN STREET DARLINGTON LIFE STYLE EXPRESS 173, NORTH ROAD DARLINGTON BEST ONE (SEEMA NEWS) 221, NORTH ROAD DARLINGTON PHEONIX STORES 1-2 SPRINGFIELD ROAD DARLINGTON MC COLLS WHITE HART CRESCENT DARLINGTON MANDIP SINGH BAINS HARROWGATE -

We'll Help You Tap Into Tesco Expertise

If you’re not doing chilled properly, you’re doomed A tour around Peter Robinson’s latest shop STORE LOOKBOOK Page 8 RETAIL NEWS THAT MATTERS l £2.40 l 17.02.2017 » We’ll help you tap into Tesco expertise l Systems, support and range advice will help strengthen independent retailers l Exclusive interview with Booker chief exec Charles Wilson and retail MD Steve Fox Page 6 » things driving your magazine profits in 2017Vol 128 No 07 Page 36 » FOR TRADE USE ONLY +9 07 2 17 February 2017 RN CONTENTS Shaping the future What’s the future of independent retail for premium since 1889 tobacco? Page 32 Editor Associate editor News editor Chris Gamm Chris Rolfe Gurpreet Samrai @ChrisGammRN @ChrisRolfeRN @GurpreetS_RN 020 7689 3378 020 7689 3362 020 7689 3386 Features editor Reporter Reporter Tom Gockelen-Kozlowski Charlie Faulkner Dave Songer @TomGK_RN @CharlieFaulkRN @DaveSongerRN 020 7689 3361 020 7689 3357 020 7689 3358 Reporter Head of production Senior designer Jennifer Hardwick Darren Rackham Anne-Claire Pickard @JenniferH_RN @DarrenRackhamRN 020 7689 3391 020 7689 3350 020 7689 3373 “We know you don’t force a Designer Account managers Marketing executive retailer to do something they Emma Langschied Marta Dziok-Kaczynska Keelan Farley 020 7689 3380 020 7689 3354 020 7689 3356 don’t want to do ” Production Erin Swanson Financial controller coordinator 020 7689 3372 Parin Gohil Booker chief exec Charles Wilson Page 6 Billy Allen Marketing manager 020 7689 3375 020 7689 3368 Tom Mulready Managing director Director of sales 020 7689 3352 Nick -

Tesco/Booker Merger Inquiry Case Page

Tesco and Booker A report on the anticipated acquisition by Tesco PLC of Booker Group plc 20 December 2017 © Crown copyright 2017 You may reuse this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Website: www.gov.uk/cma Members of the Competition and Markets Authority who conducted this inquiry Simon Polito (Chair of the Group) Gavin Robert Robert Spedding Tim Tutton Chief Executive of the Competition and Markets Authority Andrea Coscelli The Competition and Markets Authority has excluded from this published version of the provisional findings report information which the inquiry group considers should be excluded having regard to the three considerations set out in section 244 of the Enterprise Act 2002 (specified information: considerations relevant to disclosure). The omissions are indicated by []. Some numbers have been replaced by a range. These are shown in square brackets. Non-sensitive wording is also indicated in square brackets. Contents Page Summary .................................................................................................................... 3 Findings .................................................................................................................... 16 1. The reference ....................................................................................................