Conflict Escalation Scenarios and De-Escalation Pathways in South Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page3local.Qxd (Page 1)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2019 (PAGE 3) Impart quality education to India, Russia against outside influence students: Guv to teachers Modi briefs Putin on J&K decision, Excelsior Correspondent SRINAGAR, Sept 4: Governor Satya Pal Malik has greet- thanks him for support ed people particularly the teaching fraternity on the occasion VLADIVOSTOK, Sept 4: of Teachers’ Day which is celebrated in honour of Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, an eminent Indian teacher, philoso- With Russia firmly backing pher and statesman who served as the first Vice President of India on Kashmir, Prime Minister India (1952–1962) and the second President of India (1962 Narendra Modi today thanked to 1967). President Vladimir Putin for his In his message, Governor observed that Teachers’ Day is a support, explained the rationale very special occasion for recognizing and paying tribute to the behind the Government's move vital role played by teachers and honouring eminent teachers Union Minister Prahlad Singh Patel chairing a meeting of LAHDC at Leh. and apprised him of the "false and for their contributions in varied fields of learning and research. misleading" propaganda by Governor observed teachers are a very important element of Pakistan. Ladakh Festival concludes the society and deserve high respect for their instructing and During his summit talks with grooming the upcoming generations. He called upon the entire President Putin here in the Far Union Minister assures to reconsider Swadesh Darshan fraternity of teachers to put in their best efforts for imparting qual- Eastern port city, Prime Minister ity education to the youth and, besides, also encourage their holis- Modi himself brought up the Excelsior Correspondent Facilitator Programme (TFP) by cum Planetarium, tic development. -

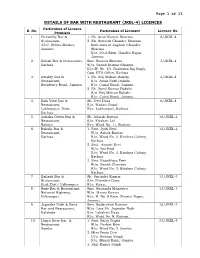

JKEL-4) LICENCES Particulars of Licence S

Page 1 of 13 DETAILS OF BAR WITH RESTAURANT (JKEL-4) LICENCES Particulars of Licence S. No. Particulars of Licensee Licence No. Premises 1. Piccadilly Bar & 1. Sh. Arun Kumar Sharma 2/JKEL-4 Restaurant, 2. Sh. Romesh Chander Sharma 23-C, Nehru Market, both sons of Jagdish Chander Jammu Sharma R/o. 20-A Extn. Gandhi Nagar, Jammu. 2. Satish Bar & Restaurant, Smt. Suman Sharma 3/JKEL-4 Kathua W/o. Satish Kumar Sharma R/o W. No. 10, Chabutra Raj Bagh, Opp. ETO Office, Kathua 3. Kwality Bar & 1. Sh. Brij Mohan Bakshi 4/JKEL-4 Restaurant, S/o. Amar Nath Bakshi Residency Road, Jammu R/o. Canal Road, Jammu. 2. Sh. Sunil Kumar Bakshi S/o. Brij Mohan Bakshi R/o. Canal Road, Jammu. 4. Ravi View Bar & Sh. Devi Dass 8/JKEL-4 Restaurant, S/o. Madan Gopal Lakhanpur, Distt. R/o. Lakhanpur, Kathua. Kathua. 5. Ashoka Green Bar & Sh. Adarsh Rattan 10/JKEL-4 Restaurant, S/o. Krishan Lal Rajouri R/o. Ward No. 11, Rajouri. 6. Bakshi Bar & 1. Smt. Jyoti Devi 12/JKEL-4 Restaurant, W/o. Ashok Kumar Kathua. R/o. Ward No. 3, Krishna Colony, Kathua. 2. Smt . Amarti Devi W/o. Sat Paul R/o. Ward No. 3, Krishna Colony, Kathua. 3. Smt. Kaushlaya Devi W/o. Satish Chander R/o. Ward No. 3, Krishna Colony, Kathua. 7. Kailash Bar & Sh. Surinder Kumar 13/JKEL-4 Restaurant, S/o. Pitamber Dass Kud, Distt. Udhampur. R/o. Katra. 8. Roxy Bar & Restaurant, Smt. Sunanda Mangotra 14/JKEL-4 National Highway, W/o. -

A Study of Sacred Groves Existing in Different Religious Patches of Poonch District

P: ISSN No. 2231-0045 RNI No. UPBIL/2012/55438 VOL.-IV, ISSUE-I, August-2015 E: ISSN No. 2349-9435 Periodic Research A Study of Sacred Groves Existing in Different Religious Patches of Poonch District Abstract The practice of dedicating groves to local deities has a long history. They are the ancient natural sanctuaries where all forms of living Please Send creatures are given protection by deity. These sacred groves have been traditional means of biodiversity are the patches of forest that support one passport forest-dwelling species within non-forest matrix. Sacred groves are not size photo in only the sacred ecosystems functioning as a rich repository of nature‟s our mail id unique biodiversity, but also a product of the socio-ecological philosophy, our forefathers have been cherishing since olden days. Many of these pristine ecosystems have either vanished or are disturbed to a great extent. But those still existing are living instances of Carbon pools and nature‟s preserved uniqueness. Rani Mughal Poonch district is the land of saints, sages, great philosophers Designation . ………………., and mystics.There are several sacred groves having rich diverse flora Deptt. of Botany, and their documentation did not get any attention so far. The present piece of work comprises study of 9 such most popular sacred groves in Govt. Degree College, which woody flora belonging to 24 families was observed with dominance Poonch of the family Rosaceae. Keywords: Biodiversity, Documentation, Flora, Sacred Groves, Socio- Ecological Philosophy, Wood. Introduction Sacred groves are the excellent traditional concept to maintain environment at village or regional level. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

NOTICE FOR APPOINTMENT OF REGULAR / RURAL RETAIL OUTLET DEALERSHIPS BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED (BPCL) PROPOSES TO APPOINT RETAIL OUTLET DEALERS IN THE STATE OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR AS PER FOLLOWING DETAILS: Estimated Fixed Fee / Security Minimum Dimension Type of monthly Type of Finance to be arranged by the Mode of Minimum Bid Deposit Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Category (in M.)/Area of the site (in Sq. RO Sales Site* applicant Selection amount (Rs.in (Rs.in M.). * Potential # Lakhs ) Lakhs ) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 CC / DC / SC CFS SC CC-1 SC CC-2 SC PH ST Estimated Estimated fund ST CC-1 working required for Regular / MS+HSD ST CC-2 capital Draw of Lots ST PH Frontage Depth Area development of Rural in Kls requirement / Bidding OBC infrastructure for operation OBC CC-1 at RO of RO OBC CC-2 OBC PH OPEN OPEN CC-1 OPEN CC-2 OPEN PH 1 Vill Khanpur on vijaypur to Khanpur road SAMBA RURAL 65 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 2 Village Madana, Purmandal Road SAMBA RURAL 60 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 3 VILLAGE DHOK JAGIR ON AKHNOOR TO KALEETH ROAD JAMMU RURAL 100 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 4 Village Nagrota(Between Ziyarat & Temple) LHS on Rajouri Budhal RoadRAJOURI RURAL 100 ST CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 5 Village Kotdhara (on Peeri to Rajouri Road) RAJOURI RURAL 30 ST CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 6 Village Magam on Magam to Pattan road BARAMULLA RURAL 75 ST CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 7 Hillar road, verinag to Qazigund ANANTNAG RURAL 50 ST CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of -

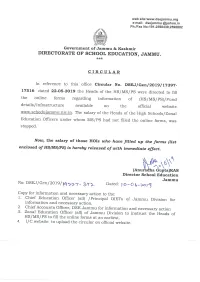

Circular on Drawal of Salary

LIST OF SCHOOLS WHO HAVE FILLED THE FORM TILL 10-6-19 S.NO DISTRICT NAME OF SCHOOL TYPE NAME OF INCHARGE 1 DODA BHALESSA HS THALORAN HS DEYAL SINGH PARIHAR 2 DODA ASSAR HS KALHOTA HS MOHD IQBAL 3 DODA ASSAR HS BAGAR HS RUKHSANA KOUSAR 4 DODA ASSAR HS BULANDPUR HS SURESH KUMAR 5 DODA ASSAR HS HAMBAL HS ROMESH CHANDER 6 DODA ASSAR LOWERHS JATHI HS NAZIR HUSSAIN 7 DODA ASSAR HS BARRI HS MOHD SAFDER 8 DODA ASSAR HS MANGOTA HS MOHD SAFDER 9 DODA ASSAR HS MALHORI HS YOG RAJ 10 DODA ASSAR HS THANDA PANI HS KULDEEP RAJ 11 DODA ASSAR HS ROAT HS MOHD ASSDULLAH 12 DODA ASSAR HS MOOTHI HS JAVED HUSSAIN 13 DODA BHADARWAH LHS NAGAR HS NUSRAT JAHAN 14 DODA BHADARWAH HS MATHOLA HS SHAHEEN BEGUM 15 DODA BHADARWAH GHS MANTHLA HS SAYEDA BEGUM 16 DODA BHADARWAH HS THANALLA HS AJIT SINGH MANHAS 17 DODA BHADARWAH HS BHEJA BHADERWAH HS MUMTAZ BEGUM 18 DODA BHAGWAH HS SOOLI HS GHULAM MOHD 19 DODA BHALESSA GHS KILHOTRAN HS(G) MOHD ABASS 20 DODA BHALESSA HS BATARA HS ABDUL RASHID 21 DODA BHALESSA HS DHAREWRI HS MOHD SHAFI KHAN 22 DODA BHALESSA HS BHARGI HS KHATAM HUSSAIN 23 DODA BHALESSA HS BHARTHI HS TALKING HUSSAIN 24 DODA BHALESSA HS ALNI HS TALIB HUSSAIN 25 DODA BHALESSA HS GANGOTA HS JAVID IQBALL MASTER 26 DODA BHALLA HS SERI HS SHAHEENA AKHTER 27 DODA BHALLA GHS CHATTRA HS HEADMASTER 28 DODA BHALLA HS BHAGRATHA HS KULBIR SINGH 29 DODA BHATYAD HS HADDAL HS MOHD ASLAM INCHARGE 30 DODA BHATYAS GHS CHILLY BALLA HS(G) RAM LAL 31 DODA BHATYAS HS TILOGRA HS ROMESH CHANDER 32 DODA BHATYAS HS CHAMPAL HS OM PARKASH 33 DODA BHATYAS HS KAHARA HS PIAR SINGH 34 DODA BHATYAS -

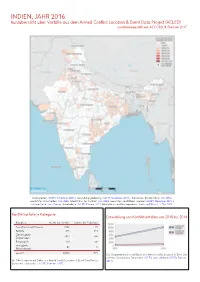

INDIEN, JAHR 2016: Kurzübersicht Über Vorfälle Aus Dem Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Zusammengestellt Von ACCORD, 9

INDIEN, JAHR 2016: Kurzübersicht über Vorfälle aus dem Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) zusammengestellt von ACCORD, 9. Februar 2017 Staatsgrenzen: GADM, November 2015a; Verwaltungsgliederung: GADM, November 2015b; Grenzstatus Bhutan/China: CIA, 2012; Grenzstatus China/Indien: CIA, 2006; Grenzstatus des Kashmir: CIA, 2004; Geo-Daten umstrittener Grenzen: GADM, November 2015a; Natural Earth, ohne Datum; Vorfallsdaten: ACLED, Februar 2017; Küstenlinien und Binnengewässer: Smith und Wessel, 1. Mai 2015 Konfliktvorfälle je Kategorie Entwicklung von Konfliktvorfällen von 2015 bis 2016 Kategorie Anzahl der Vorfälle Summe der Todesfälle Ausschreitungen/Proteste 9366 92 Kämpfe 475 613 Gewalt gegen 422 246 Zivilpersonen Fernangriffe 110 46 strategische 89 0 Entwicklungen gesamt 10462 997 Das Diagramm basiert auf Daten des Armed Conflict Location & Event Da- ta Project (verwendete Datensätze: ACLED, April 2016und ACLED, Februar Die Tabelle basiert auf Daten des Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project 2017). (verwendete Datensätze: ACLED, Februar 2017) INDIEN, JAHR 2016: KURZÜBERSICHT ÜBER VORFÄLLE AUS DEM ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) ZUSAMMENGESTELLT VON ACCORD, 9. FEBRUAR 2017 LOKALISIERUNG DER KONFLIKTVORFÄLLE Hinweis: Die folgende Liste stellt einen Überblick über Ereignisse aus den ACLED-Datensätzen dar. Die Datensätze selbst enthalten weitere Details (Ortsangaben, Datum, Art, beteiligte AkteurInnen, Quellen, etc.). In der Liste werden für die Orte die Namen in der Schreibweise von ACLED verwendet, -

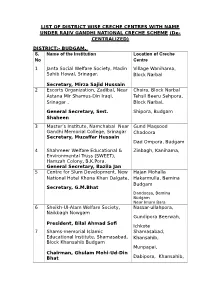

LIST of DISTRICT WISE CRECHE CENTRES with NAME UNDER RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL CRECHE SCHEME (De- CENTRALIZED)

LIST OF DISTRICT WISE CRECHE CENTRES WITH NAME UNDER RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL CRECHE SCHEME (De- CENTRALIZED) DISTRICT:- BUDGAM. S. Name of the Institution Location of Creche No Centre 1 Janta Social Welfare Society, Madin Village Wanihama, Sahib Hawal, Srinagar. Block Narbal Secretary, Mirza Sajid Hussain 2 Escorts Organization, Zadibal, Near Chaira, Block Narbal Astana Mir Shamus-Din Iraqi, Tehsil Beeru Sehpora, Srinagar . Block Narbal, General Secretary, Smt. Shipora, Budgam Shaheen 3 Master’s Institute, Namchabal Near Gund Maqsood Gandhi Memorial College, Srinagar Chadoora Secretary, Muzaffar Hussain Dad Ompora, Budgam 4 Shahmeer Welfare Educational & Zinbagh, Kanihama, Environmental Truss (SWEET), Hamzah Colony, B.K.Pora. General Secretary, Bazila Jan 5 Centre for Slum Development, New Hajan Mohalla National Hotel Khona Khan Dalgate, Hakarmulla, Bemina Budgam Secretary, G.M.Bhat Dandoosa, Bemina Budgam Near Imam Bara 6 Sheikh-Ul-Alam Welfare Society, Nassar-ullahpora, Naikbagh Nowgam Gundipora Beerwah, President, Bilal Ahmad Sof Ichkote 7 Shams-memorial Islamic Shamasabad, Educational Institute, Shamasabad, Khansahib, Block Khansahib Budgam Munpapai, Chairman, Ghulam Mohi-Ud-Din Bhat Dabipora, Khansahib, Braripora 8 Allamdar Social Welfare Society, Hushroo, Block Shamas abad Budgam Chandoora, Raithan, Block Khansahib, Chairman, Mohd Ramzan Bhat Kachwari, Porvora, Chandoora, Ichikoot, 9 NEAT NGO Education & Training B.K.Pora Chief Administrator, S.M Aslam Wahab Pora 10 Tameer-e-Mashira (NGO), Gulshan B.K.Pora Nagar Sringar Kral Pora President, Sajad Ahmad 11 Mother Land Women Welfare Alipora, Budgam Society, Srinagar Secretary, Mehjabeen Kamli 12 Welfare Project, Bugdam. Cheki Kawoosa Distt: Budgam. Sheelipura Chairman, Master Mohd. Dist:Budagm. Maqbool Nasrullapora. Distt:Budgam. Utilgam, Distt:Budgam PanzanChadora. Distt:Budgam Kenihama Chadora. -

Geographical Boundaries of District Poonch

Annexure to Notification SRO 447 dated 21 st October, 2014 Jurisdiction of Sub-Divisions of District Poonch Sub Division Headquartered at Tehsil Mendhar (Existing) Mendhar 1. Mendhar (Existing) 2. Balakote (New) 3. Mankote (New) Surankote (New) Surankote 1. Surankote (Existing) Area under the District HQ Poonch 1. Haveli (Existing) direct control of 2. Mandi (Existing) Deputy Commissioner, Poonch Re-Organized Geographical limits of the existing and new administrative units of district Poonch Name of the Name of the Name of Niabat Name of Patwar Name of the Sub Tehsil Halqa Revenue village Division District HQ Haveli 1.Haveli (Existing) 1.Sher khas 1. Sher Khas Poonch (Existing) 2.Dara Bagyal 1. Banvat 2. Dhokri 3. Dara Bagyal 4. Degwar Terwan 5. Dallan 2. Khaneter- 1. Khaneter 1. Khaneter Kanuyian (New) 2. Mangnar 1. Kuniyan HQ at Bainchh 2. Bhainch 3. Mangnar 3.Dara Dullian 1. Jhulass 1. Dara Dullian (New) HQ at Dara 2. Jhulass Dullian Near 3. Salootri Government High 4. Mendla (Un- School (Ziarat) inhabitated) 4. Gulpur (New) 2. Gulpur 1. Gulpur HQ at Gulpur 2. Dharamsal proper Khari 3. Karmara 4. Kosalian 5. Tetrinote (Un- inhabitated) 6. Polas 2. Degwar 1. Ajote Maldiyalan 2. Degwar Maldiyalan 3. Noorkote 4. Nakarkote 5. Seerian 5. Bandichechian 1. Bandichechian 1. Bandichechian (New) HQ at 2. Qasba Bandichechian 3. Kankote 2.Shahpur 1. Kirni 2. Mandhar 3. Shahpur 4. Islamabad 3.Nangali 1. Saral 2. Nangali 3. Noonabandi 6. Chandak 1.Chandak 1. Chandak (Existing) 2. Chaktroo 3. Timbra 4. Dana Doyian 5. Dingla 6. Janyar 2.Seri Khawaja 1. Seri Khawaja 2. -

Pakistan Deputy High Commissioner Summoned and Protest Lodged at the Killing of 5 Innocent Civilians in Unprovoked Firing by Pakistan Forces

Home › Media Center › Press Releases Pakistan Deputy High Commissioner summoned and protest lodged at the killing of 5 innocent civilians in unprovoked firing by Pakistan forces March 19, 2018 The Deputy High Commissioner of Pakistan, Syed Haider Shah was summoned today and strong protest was lodged at the loss of lives of five innocent Indian civilians (a family comprising of husband, wife and three children) and grievous injuries to two other minor children in unprovoked ceasefire violations by Pakistan forces on 18 March 2018 in Bhimber Gali Sector across the Line of Control in the Indian state of Jammu & Kashmir. It was conveyed that the deliberate targeting of innocent civilians, who are located two kilometers away from the forward line of defences, by Pakistan forces using high caliber weapons, is highly deplorable and is condemned in the strongest terms. Such heinous acts are against established humanitarian norms and professional military conduct. Pakistan authorities are called upon to investigate into such heinous acts and instruct its forces to desist from such acts immediately. Our strong concerns were shared at continued unprovoked firing and ceasefire violations across the Line of Control and the International Border. More than 560 such violations have been carried out by Pakistan forces at the Line of Control so far during 2018 in which 23 Indian civilians have been killed and 70 other have been injured. The Pakistan side was also asked to end the support being given to cross border infiltration of terrorists, including through covering fire. New Delhi March 19, 2018 Comments Terms & Conditions Privacy Policy Copyright Policy Hyperlinking Policy Accessibility Statement Help © Content Owned by Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. -

A Study of Sacred Groves Existing in Different Religious Patches of Poonch District

P: ISSN No. 2231-0045 RNI No. UPBIL/2012/55438 VOL.-IV, ISSUE-I, August-2015 E: ISSN No. 2349-9435 Periodic Research A Study of Sacred Groves Existing in Different Religious Patches of Poonch District Abstract The practice of dedicating groves to local deities has a long history. They are the ancient natural sanctuaries where all forms of living creatures are given protection by deity. These sacred groves have been traditional means of biodiversity are the patches of forest that support forest-dwelling species within non-forest matrix. Sacred groves are not only the sacred ecosystems functioning as a rich repository of nature‟s unique biodiversity, but also a product of the socio-ecological philosophy, our forefathers have been cherishing since olden days. Many of these pristine ecosystems have either vanished or are disturbed to a great extent. But those still existing are living instances of Carbon pools and nature‟s preserved uniqueness. Rani Mughal Poonch district is the land of saints, sages, great philosophers Sr. Assistant Professor, and mystics.There are several sacred groves having rich diverse flora Deptt. of Botany, and their documentation did not get any attention so far. The present piece of work comprises study of 9 such most popular sacred groves in Govt. Degree College, which woody flora belonging to 24 families was observed with dominance Poonch of the family Rosaceae. Keywords: Biodiversity, Documentation, Flora, Sacred Groves, Socio- Ecological Philosophy, Wood. Introduction Sacred groves are the excellent traditional concept to maintain environment at village or regional level. The sacred groves consist of a Shrine for the God / Goddess with a pond tank surrounded by a small forest or dense trees. -

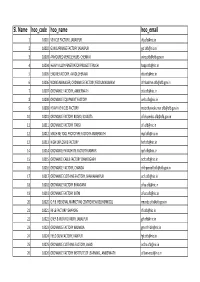

Sl. Name Hoo Code Hoo Name Hoo Email

Sl. Name hoo_code hoo_name hoo_email 1 10001 VEHICLE FACTORY, JABALPUR [email protected] 2 10002 GUN CARRIAGE FACTORY JABALPUR [email protected] 3 10003 ARMOURED VEHICLE HQRS. CHENNAI [email protected] 4 10004 HEAVY ALLOY PENETRATOR PROJECT TIRUCHI [email protected] 5 10005 ENGINE FACTORY, AVADI,CHENNAI [email protected] 6 10006 WORKS MANAGER, ORDNANCE FACTORY,YEDDUMAILARAM [email protected] 7 10007 ORDNANCE FACTORY, AMBERNATH [email protected] 8 10008 ORDNANCE EQUIPMENT FACTORY [email protected] 9 10009 HEAVY VEHICLES FACTORY [email protected] 10 10010 ORDNANCE FACTORY BOARD, KOLKATA [email protected] 11 10011 ORDNANCE FACTORY ITARSI [email protected] 12 10012 MACHINE TOOL PROTOTYPE FACTORY AMBERNATH [email protected] 13 10013 HIGH EXPLOSIVE FACTORY [email protected] 14 10014 ORDNANCE PARACHUTE FACTORY KANPUR [email protected] 15 10015 ORDNANCE CABLE FACTORY CHANDIGARH [email protected] 16 10016 ORDNANCE FACTORY, CHANDA [email protected] 17 10017 ORDNANCE CLOTHING FACTORY, SHAHJAHANPUR [email protected] 18 10018 ORDNANCE FACTORY BHANDARA [email protected] 19 10019 ORDNANCE FACTORY KATNI [email protected] 20 10020 O.F.B. REGIONAL MARKETING CENTRE NEW DELHI(RMCDL) [email protected] 21 10021 RIFLE FACTORY ISHAPORE [email protected] 22 10022 GREY & IRON FOUNDRY, JABALPUR [email protected] 23 10023 ORDNANCE FACTORY NALANDA gm‐ofn‐[email protected] 24 10024 FIELD GUN FACTORY, KANPUR [email protected] 25 10025 ORDNANCE CLOTHING FACTORY, AVADI [email protected] 26 10026 ORDNANCE FACTORY INSTITUTE OF LEARNING , AMBERNATH ofilam‐[email protected] 27 10027 OFB, -

Page1.Qxd (Page 2)

daily Vol No. 54 No. 361 JAMMU, MONDAY, DECEMBER 31, 2018 REGD. NO. JK-71/18-20 12 Pages ` 5.00 ExcelsiorRNI No. 28547/65 Mrinal Sen Only incapacitated & those with bad record to be removed Troops well passes away prepared: Rawat KOLKATA, Dec 30: Dadasaheb Phalke award- Admn withdraws order, allows ABU ROAD (RAJ), Dec 30: winning film director Mrinal Army chief General Bipin Sen passed Rawat today said soldiers of the away today country are always prepared to after a pro- VDC members to continue fight the problems of terrorism longed bat- and naxalism. tle with Speaking at an event organ- age-related VDCs to be further strengthened, trained ised here by spiritual group ailments, Brahmkumaris, General Rawat family Sanjeev Pargal those members, who were inca- members, who had turned 60, said those who serve their sources said. He was 95. pacitated or have criminal leading to panic among the mothers and the motherland get minorities in Doda, Kishtwar The Padma Bhushan JAMMU, Dec 30: record and not from all. heaven. "All VDC members of 60 and Ramban districts, where the awardee, best known for films Authorities have withdrawn Serving mother and mother- people had braved militancy for their decision to take back years or above, who have good land is similar. Not everyone such “Neel Akasher Neechey”, nearly three decades with help weapons from the Village record and can fight the militan- has luck to serve them. Those “Bhuvan Shome”, “Ek Din of the VDCs and didn't migrate. Defence Committee (VDC) cy, would continue to hold the who serve them get heaven.