Shooter's Flinch and Other Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

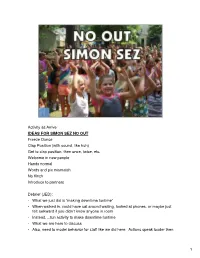

Activity As Arrive IDEAS for SIMON SEZ NO out Freeze Dance Clap Position (With Sound, Like Huh) Get to Clap Position, Then Once, Twice, Etc

Activity as Arrive IDEAS FOR SIMON SEZ NO OUT Freeze Dance Clap Position (with sound, like huh) Get to clap position, then once, twice, etc. Welcome in new people Hands normal Words and pix mismatch No flinch Introduce to partners Debrief (JED): - What we just did is “making downtime funtime” - When walked in, could have sat around waiting, looked at phones, or maybe just felt awkward if you didn’t know anyone in room - Instead….fun activity to make downtime funtime - What we are here to discuss - Also, need to model behavior for staff like we did here. Actions speak louder then 1 words….need to walk the talk! - Bonus Debrief! (ROZ) - Why great camp game? - For those that focus on building life skills or 21 st century skills, does it in a fun way…. - Listening Skills - Cooperation/ collaboration (instead of competition) - OK to laugh at yourself - Practice makes you better at everything! - Everyone can have a seat…. 1 ROZ 3:30 – 5 MRPA Thanks for joining us. Announcements from Conference…. Love this session because lots of play. ALSO….a fun benefit of technology…you are going to help determine the content in a few minutes. Going to talk about how you make every minute of the camp day a unique & special part of the experience. We will explore the different times in the camp day when staff can easily transition down-time into fun-time using creative games, activities, songs, dances and more. Can email presentation. Don’t waste paper…give cards at end to email or sign 3 sheet. -

Resource Manual EL Education Language Arts Curriculum

Language Arts Grades K-2: Reading Foundations Skills Block Resource Manual EL Education Language Arts Curriculum K-2 Reading Foundations Skills Block: Resource Manual EL Education Language Arts Curriculum is published by: EL Education 247 W. 35th Street, 8th Floor New York, NY 10001 www.ELeducation.org ISBN 978-1683622710 FIRST EDITION © 2016 EL Education Inc. Except where otherwise noted, EL Education’s Language Arts Curriculum is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/. Licensed third party content noted as such in this curriculum is the property of the respective copyright owner and not subject to the CC BY 4.0 License. Responsibility for securing any necessary permissions as to such third party content rests with parties desiring to use such content. For example, certain third party content may not be reproduced or distributed (outside the scope of fair use) without additional permissions from the content owner and it is the responsibility of the person seeking to reproduce or distribute this curriculum to either secure those permissions or remove the applicable content before reproduction or distribution. Common Core State Standards © Copyright 2010. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and Council of Chief State School Officers. All rights reserved. Common Core State Standards are subject to the public license located at http://www.corestandards.org/public-license/. Cover art from “First Come the Eggs,” a project by third grade students at Genesee Community Charter School. Used courtesy of Genesee Community Charter School, Rochester, NY. -

Scouting Games. 61 Horse and Rider 54 1

The MacScouter's Big Book of Games Volume 2: Games for Older Scouts Compiled by Gary Hendra and Gary Yerkes www.macscouter.com/Games Table of Contents Title Page Title Page Introduction 1 Radio Isotope 11 Introduction to Camp Games for Older Rat Trap Race 12 Scouts 1 Reactor Transporter 12 Tripod Lashing 12 Camp Games for Older Scouts 2 Map Symbol Relay 12 Flying Saucer Kim's 2 Height Measuring 12 Pack Relay 2 Nature Kim's Game 12 Sloppy Camp 2 Bombing The Camp 13 Tent Pitching 2 Invisible Kim's 13 Tent Strik'n Contest 2 Kim's Game 13 Remote Clove Hitch 3 Candle Relay 13 Compass Course 3 Lifeline Relay 13 Compass Facing 3 Spoon Race 14 Map Orienteering 3 Wet T-Shirt Relay 14 Flapjack Flipping 3 Capture The Flag 14 Bow Saw Relay 3 Crossing The Gap 14 Match Lighting 4 Scavenger Hunt Games 15 String Burning Race 4 Scouting Scavenger Hunt 15 Water Boiling Race 4 Demonstrations 15 Bandage Relay 4 Space Age Technology 16 Firemans Drag Relay 4 Machines 16 Stretcher Race 4 Camera 16 Two-Man Carry Race 5 One is One 16 British Bulldog 5 Sensational 16 Catch Ten 5 One Square 16 Caterpillar Race 5 Tape Recorder 17 Crows And Cranes 5 Elephant Roll 6 Water Games 18 Granny's Footsteps 6 A Little Inconvenience 18 Guard The Fort 6 Slash hike 18 Hit The Can 6 Monster Relay 18 Island Hopping 6 Save the Insulin 19 Jack's Alive 7 Marathon Obstacle Race 19 Jump The Shot 7 Punctured Drum 19 Lassoing The Steer 7 Floating Fire Bombardment 19 Luck Relay 7 Mystery Meal 19 Pocket Rope 7 Operation Neptune 19 Ring On A String 8 Pyjama Relay 20 Shoot The Gap 8 Candle -

Roberts Papers, 1973-77

John W. “Bill” Roberts Papers, 1973-77 Oral Diary, July 24-September 12, 1974 In 1991, Bill Roberts donated to the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library 14 linear feet of papers covering his work as an assistant press secretary to Gerald R. Ford during both the vice presidency and presidency. The collection includes Roberts's personal observations and recollections, which he tape- recorded every few days during July, August, and September 1974. These recollections, on four audio cassettes, provide insight into the last days of the Ford vice presidency, the transition to the presidency, and the persons and personalities involved in the events. The diary begins and ends abruptly, and it is sporadic. It covers only this brief period in time and is not part of a more complete diary. The Ford Library created the transcript that appears on succeeding pages of this document. Roberts, 7/24/74-9/12/74 - 1 July 24, 1974 Wednesday I'm starting this recording on July 24th. On the morning of July 24th, the Supreme Court, 8-0, ordered the President to surrender the tapes. The Vice President heard about this shortly after the Court decision was made public and decided that he wouldn't say anything as far as the press was concerned until or unless the President made some sort of response. We had quite a problem in fending off the press inquiries which were coming in at a great rate. The complicating factor was that CBS that day had chosen and been given the chance to follow the Vice President wherever he went, photograph him, and do a day in the life of the Vice President. -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ............................................................................................................................... -

The Road to Afghanistan

Introduction Hundreds of books—memoirs, histories, fiction, poetry, chronicles of military units, and journalistic essays—have been written about the Soviet war in Afghanistan. If the topic has not yet been entirely exhausted, it certainly has been very well documented. But what led up to the invasion? How was the decision to bring troops into Afghanistan made? What was the basis for the decision? Who opposed the intervention and who had the final word? And what kind of mystical country is this that lures, with an almost maniacal insistence, the most powerful world states into its snares? In the nineteenth and early twentieth century it was the British, in the 1980s it was the Soviet Union, and now America and its allies continue the legacy. Impoverished and incredibly backward Afghanistan, strange as it may seem, is not just a normal country. Due to its strategically important location in the center of Asia, the mountainous country has long been in the sights of more than its immediate neighbors. But woe to anyone who arrives there with weapon in hand, hoping for an easy gain—the barefoot and illiterate Afghans consistently bury the hopes of the strange foreign soldiers who arrive along with battalions of tanks and strategic bombers. To understand Afghanistan is to see into your own future. To comprehend what happened there, what happens there continually, is to avoid great tragedy. One of the critical moments in the modern history of Afghanistan is the period from April 27, 1978, when the “April Revolution” took place in Kabul and the leftist People’s Democratic Party seized control of the country, until December 27, 1979, when Soviet special forces, obeying their “international duty,” eliminated the ruling leader and installed 1 another leader of the same party in his place. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

CONSTITUTIONAL COURT of SOUTH AFRICA Case CCT 311/17 in the Matter Between: GELYKE KANSE First Applicant DANIËL JOHANNES ROSSOU

CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA Case CCT 311/17 In the matter between: GELYKE KANSE First Applicant DANIËL JOHANNES ROSSOUW Second Applicant PRESIDENT OF THE CONVOCATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH Third Applicant BERNARDUS LAMBERTUS PIETERS Fourth Applicant MORTIMER BESTER Fifth Applicant JAKOBUS PETRUS ROUX Sixth Applicant FRANCOIS HENNING Seventh Applicant ASHWIN MALOY Eighth Applicant RODERICK EMILE LEONARD Ninth Applicant and CHAIRPERSON OF THE SENATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH First Respondent CHAIRPERSON OF THE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH Second Respondent UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH Third Respondent Neutral citation: Gelyke Kanse and Others v Chairperson of the Senate of the University of Stellenbosch and Others [2019] ZACC 38 Coram: Mogoeng CJ, Cameron J, Froneman J, Jafta J, Khampepe J, Madlanga J, Mathopo AJ, Mhlantla J, Theron J, Victor AJ Judgments: Cameron J (unanimous): [1] to [51] Mogoeng CJ (concurring): [52] to [63] Froneman J (concurring): [64] to [98] Heard on: 8 August 2019 Decided on: 10 October 2019 Summary: Section 29(2) of the Constitution — “reasonably practicable” — constitutionality of the language policy of the University of Stellenbosch — Afrikaans as a medium of instruction – access to higher education Section 6 of the Constitution — protection and promotion of indigenous minority languages — diminished use and status ORDER On direct appeal from the High Court of South Africa, Western Cape Division, Cape Town: 1. Leave to appeal is granted. 2. The appeal is dismissed, with no order as to costs in this Court. 3. The costs orders in the High Court are set aside. 4. In their place is substituted: “There is no order as to costs.” 2 JUDGMENT CAMERON J (Mogoeng CJ, Froneman J, Jafta J, Khampepe J, Madlanga J, Mathopo AJ, Mhlantla J, Theron J and Victor AJ concurring): Introduction [1] At issue is the 2016 Language Policy (2016 Language Policy) of Stellenbosch University, the third respondent. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

Less Than Exciting Behaviors Associated with Unneutered

1 c Less Than Exciting ASPCA Behaviors Associated With Unneutered Male Dogs! Periodic binges of household destruction, digging and scratching. Indoor restlessness/irritability. N ATIONAL Pacing, whining, unable to settle down or focus. Door dashing, fence jumping and assorted escape behaviors; wandering/roaming. Baying, howling, overbarking. Barking/lunging at passersby, fence fighting. Lunging/barking at and fighting with other male dogs. S HELTER Noncompliant, pushy and bossy attitude towards caretakers and strangers. Lack of cooperation. Resistant; an unwillingness to obey commands; refusal to come when called. Pulling/dragging of handler outdoors; excessive sniffing; licking female urine. O UTREACH Sexual frustration; excessive grooming of genital area. Sexual excitement when petted. Offensive growling, snapping, biting, mounting people and objects. Masturbation. A heightened sense of territoriality, marking with urine indoors. Excessive marking on outdoor scent posts. The behaviors described above can be attributed to unneutered male sexuality. The male horomone D testosterone acts as an accelerant making the dog more reactive. As a male puppy matures and enters o adolescence his primary social focus shifts from people to dogs; the human/canine bond becomes g secondary. The limited attention span will make any type of training difficult at best. C a If you are thinking about breeding your dog so he can experience sexual fulfillment ... don’t do it! This r will only let the dog ‘know what he’s missing’ and will elevate his level of frustration. If you have any of e the problems listed above, they will probably get worse; if you do not, their onset may be just around the corner. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Un Scénario De Julien Rappeneau & Jérome Salle

Un scénario de Julien Rappeneau & Jérome Salle – Publication à but éducatif uniquement – Tous droits réservés - Merci de respecter le droit d’auteur et de mentionner vos sources si vous citez tout ou partie d’un scénario. ZULU Screenplay by Julien Rappeneau and Jérôme Salle Based on the novel by Caryl Férey A film by Jérôme Salle September 21 2012 "Forgiveness liberates the soul. It removes fear That is why it is such a powerful weapon." Nelson Mandela 2. 1 INT. KWAZULU-NATAL TOWNSHIP / ALI’S HOUSE - NIGHT 1 CU on a ten-year-old black child, Ali Sokhela. His face is pressed up to the window. ALI (frightened) Baba... Daddy... Outside, some twenty men in a state of frenzy throw a thirty- year-old black man to the ground. They hit him, insult him, screaming “This is what we do with scum like you!” “All you ANC shits will die!” “We’re gonna fry him like a pig!” KWAZULU-NATAL - SOUTH AFRICA - 1978 A tire is put around the man’s neck. The men throw a lit lighter at him. The tire bursts into flames. Screams of pain blend in with the torturers’ screams of joy. Still pressed up to the window, Ali’s face is lit by the flames. Suddenly a hooded man appears right in front of him, on the other side of the window. Terrified, Ali jumps back. He rushes for the door. Just as he reaches it, two hands try to grab him. He barely escapes. 2 EXT. KWAZULU-NATAL TOWNSHIP - NIGHT 2 In only his underpants, Ali runs as fast as he can.