Quantum Logic and Its Role in Interpreting Quantum Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Lattice Structure of Quantum Logic

BULL. AUSTRAL. MATH. SOC. MOS 8106, *8IOI, 0242 VOL. I (1969), 333-340 On the lattice structure of quantum logic P. D. Finch A weak logical structure is defined as a set of boolean propositional logics in which one can define common operations of negation and implication. The set union of the boolean components of a weak logical structure is a logic of propositions which is an orthocomplemented poset, where orthocomplementation is interpreted as negation and the partial order as implication. It is shown that if one can define on this logic an operation of logical conjunction which has certain plausible properties, then the logic has the structure of an orthomodular lattice. Conversely, if the logic is an orthomodular lattice then the conjunction operation may be defined on it. 1. Introduction The axiomatic development of non-relativistic quantum mechanics leads to a quantum logic which has the structure of an orthomodular poset. Such a structure can be derived from physical considerations in a number of ways, for example, as in Gunson [7], Mackey [77], Piron [72], Varadarajan [73] and Zierler [74]. Mackey [77] has given heuristic arguments indicating that this quantum logic is, in fact, not just a poset but a lattice and that, in particular, it is isomorphic to the lattice of closed subspaces of a separable infinite dimensional Hilbert space. If one assumes that the quantum logic does have the structure of a lattice, and not just that of a poset, it is not difficult to ascertain what sort of further assumptions lead to a "coordinatisation" of the logic as the lattice of closed subspaces of Hilbert space, details will be found in Jauch [8], Piron [72], Varadarajan [73] and Zierler [74], Received 13 May 1969. -

Relational Quantum Mechanics

Relational Quantum Mechanics Matteo Smerlak† September 17, 2006 †Ecole normale sup´erieure de Lyon, F-69364 Lyon, EU E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In this internship report, we present Carlo Rovelli’s relational interpretation of quantum mechanics, focusing on its historical and conceptual roots. A critical analysis of the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen argument is then put forward, which suggests that the phenomenon of ‘quantum non-locality’ is an artifact of the orthodox interpretation, and not a physical effect. A speculative discussion of the potential import of the relational view for quantum-logic is finally proposed. Figure 0.1: Composition X, W. Kandinski (1939) 1 Acknowledgements Beyond its strictly scientific value, this Master 1 internship has been rich of encounters. Let me express hereupon my gratitude to the great people I have met. First, and foremost, I want to thank Carlo Rovelli1 for his warm welcome in Marseille, and for the unexpected trust he showed me during these six months. Thanks to his rare openness, I have had the opportunity to humbly but truly take part in active research and, what is more, to glimpse the vivid landscape of scientific creativity. One more thing: I have an immense respect for Carlo’s plainness, unaltered in spite of his renown achievements in physics. I am very grateful to Antony Valentini2, who invited me, together with Frank Hellmann, to the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, in Canada. We spent there an incredible week, meeting world-class physicists such as Lee Smolin, Jeffrey Bub or John Baez, and enthusiastic postdocs such as Etera Livine or Simone Speziale. -

Chapter 2 Introduction to Classical Propositional

CHAPTER 2 INTRODUCTION TO CLASSICAL PROPOSITIONAL LOGIC 1 Motivation and History The origins of the classical propositional logic, classical propositional calculus, as it was, and still often is called, go back to antiquity and are due to Stoic school of philosophy (3rd century B.C.), whose most eminent representative was Chryssipus. But the real development of this calculus began only in the mid-19th century and was initiated by the research done by the English math- ematician G. Boole, who is sometimes regarded as the founder of mathematical logic. The classical propositional calculus was ¯rst formulated as a formal ax- iomatic system by the eminent German logician G. Frege in 1879. The assumption underlying the formalization of classical propositional calculus are the following. Logical sentences We deal only with sentences that can always be evaluated as true or false. Such sentences are called logical sentences or proposi- tions. Hence the name propositional logic. A statement: 2 + 2 = 4 is a proposition as we assume that it is a well known and agreed upon truth. A statement: 2 + 2 = 5 is also a proposition (false. A statement:] I am pretty is modeled, if needed as a logical sentence (proposi- tion). We assume that it is false, or true. A statement: 2 + n = 5 is not a proposition; it might be true for some n, for example n=3, false for other n, for example n= 2, and moreover, we don't know what n is. Sentences of this kind are called propositional functions. We model propositional functions within propositional logic by treating propositional functions as propositions. -

![Arxiv:1511.01069V1 [Quant-Ph]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2272/arxiv-1511-01069v1-quant-ph-202272.webp)

Arxiv:1511.01069V1 [Quant-Ph]

To appear in Contemporary Physics Copenhagen Quantum Mechanics Timothy J. Hollowood Department of Physics, Swansea University, Swansea SA2 8PP, U.K. (September 2015) In our quantum mechanics courses, measurement is usually taught in passing, as an ad-hoc procedure involving the ugly collapse of the wave function. No wonder we search for more satisfying alternatives to the Copenhagen interpretation. But this overlooks the fact that the approach fits very well with modern measurement theory with its notions of the conditioned state and quantum trajectory. In addition, what we know of as the Copenhagen interpretation is a later 1950’s development and some of the earlier pioneers like Bohr did not talk of wave function collapse. In fact, if one takes these earlier ideas and mixes them with later insights of decoherence, a much more satisfying version of Copenhagen quantum mechanics emerges, one for which the collapse of the wave function is seen to be a harmless book keeping device. Along the way, we explain why chaotic systems lead to wave functions that spread out quickly on macroscopic scales implying that Schr¨odinger cat states are the norm rather than curiosities generated in physicists’ laboratories. We then describe how the conditioned state of a quantum system depends crucially on how the system is monitored illustrating this with the example of a decaying atom monitored with a time of arrival photon detector, leading to Bohr’s quantum jumps. On the other hand, other kinds of detection lead to much smoother behaviour, providing yet another example of complementarity. Finally we explain how classical behaviour emerges, including classical mechanics but also thermodynamics. -

Why Feynman Path Integration?

Journal of Uncertain Systems Vol.5, No.x, pp.xx-xx, 2011 Online at: www.jus.org.uk Why Feynman Path Integration? Jaime Nava1;∗, Juan Ferret2, Vladik Kreinovich1, Gloria Berumen1, Sandra Griffin1, and Edgar Padilla1 1Department of Computer Science, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX 79968, USA 2Department of Philosophy, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX 79968, USA Received 19 December 2009; Revised 23 February 2010 Abstract To describe physics properly, we need to take into account quantum effects. Thus, for every non- quantum physical theory, we must come up with an appropriate quantum theory. A traditional approach is to replace all the scalars in the classical description of this theory by the corresponding operators. The problem with the above approach is that due to non-commutativity of the quantum operators, two math- ematically equivalent formulations of the classical theory can lead to different (non-equivalent) quantum theories. An alternative quantization approach that directly transforms the non-quantum action functional into the appropriate quantum theory, was indeed proposed by the Nobelist Richard Feynman, under the name of path integration. Feynman path integration is not just a foundational idea, it is actually an efficient computing tool (Feynman diagrams). From the pragmatic viewpoint, Feynman path integral is a great success. However, from the founda- tional viewpoint, we still face an important question: why the Feynman's path integration formula? In this paper, we provide a natural explanation for Feynman's path integration formula. ⃝c 2010 World Academic Press, UK. All rights reserved. Keywords: Feynman path integration, independence, foundations of quantum physics 1 Why Feynman Path Integration: Formulation of the Problem Need for quantization. -

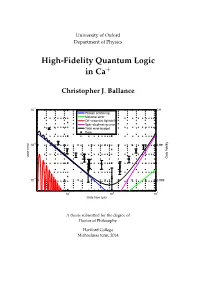

High-Fidelity Quantum Logic in Ca+

University of Oxford Department of Physics High-Fidelity Quantum Logic in Ca+ Christopher J. Ballance −1 10 0.9 Photon scattering Motional error Off−resonant lightshift Spin−dephasing error Total error budget Data −2 10 0.99 Gate error Gate fidelity −3 10 0.999 1 2 3 10 10 10 Gate time (µs) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Hertford College Michaelmas term, 2014 Abstract High-Fidelity Quantum Logic in Ca+ Christopher J. Ballance A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Michaelmas term 2014 Hertford College, Oxford Trapped atomic ions are one of the most promising systems for building a quantum computer – all of the fundamental operations needed to build a quan- tum computer have been demonstrated in such systems. The challenge now is to understand and reduce the operation errors to below the ‘fault-tolerant thresh- old’ (the level below which quantum error correction works), and to scale up the current few-qubit experiments to many qubits. This thesis describes experimen- tal work concentrated primarily on the first of these challenges. We demonstrate high-fidelity single-qubit and two-qubit (entangling) gates with errors at or be- low the fault-tolerant threshold. We also implement an entangling gate between two different species of ions, a tool which may be useful for certain scalable architectures. We study the speed/fidelity trade-off for a two-qubit phase gate implemented in 43Ca+ hyperfine trapped-ion qubits. We develop an error model which de- scribes the fundamental and technical imperfections / limitations that contribute to the measured gate error. -

Demnächst Auch in Ihrem Laptop?

The Measurement Problem Johannes Kofler Quantum Foundations Seminar Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics Munich, December 12th 2011 The measurement problem Different aspects: • How does the wavefunction collapse occur? Does it even occur at all? • How does one know whether something is a system or a measurement apparatus? When does one apply the Schrödinger equation (continuous and deterministic evolution) and when the projection postulate (discontinuous and probabilistic)? • How real is the wavefunction? Does the measurement only reveal pre-existing properties or “create reality”? Is quantum randomness reducible or irreducible? • Are there macroscopic superposition states (Schrödinger cats)? Where is the border between quantum mechanics and classical physics? The Kopenhagen interpretation • Wavefunction: mathematical tool, “catalogue of knowledge” (Schrödinger) not a description of objective reality • Measurement: leads to collapse of the wavefunction (Born rule) • Properties: wavefunction: non-realistic randomness: irreducible • “Heisenberg cut” between system and apparatus: “[T]here arises the necessity to draw a clear dividing line in the description of atomic processes, between the measuring apparatus of the observer which is described in classical concepts, and the object under observation, whose behavior is represented by a wave function.” (Heisenberg) • Classical physics as limiting case and as requirement: “It is decisive to recognize that, however far the phenomena transcend the scope of classical physical explanation, the -

David Hilbert's Contributions to Logical Theory

David Hilbert’s contributions to logical theory CURTIS FRANKS 1. A mathematician’s cast of mind Charles Sanders Peirce famously declared that “no two things could be more directly opposite than the cast of mind of the logician and that of the mathematician” (Peirce 1976, p. 595), and one who would take his word for it could only ascribe to David Hilbert that mindset opposed to the thought of his contemporaries, Frege, Gentzen, Godel,¨ Heyting, Łukasiewicz, and Skolem. They were the logicians par excellence of a generation that saw Hilbert seated at the helm of German mathematical research. Of Hilbert’s numerous scientific achievements, not one properly belongs to the domain of logic. In fact several of the great logical discoveries of the 20th century revealed deep errors in Hilbert’s intuitions—exemplifying, one might say, Peirce’s bald generalization. Yet to Peirce’s addendum that “[i]t is almost inconceivable that a man should be great in both ways” (Ibid.), Hilbert stands as perhaps history’s principle counter-example. It is to Hilbert that we owe the fundamental ideas and goals (indeed, even the name) of proof theory, the first systematic development and application of the methods (even if the field would be named only half a century later) of model theory, and the statement of the first definitive problem in recursion theory. And he did more. Beyond giving shape to the various sub-disciplines of modern logic, Hilbert brought them each under the umbrella of mainstream mathematical activity, so that for the first time in history teams of researchers shared a common sense of logic’s open problems, key concepts, and central techniques. -

Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamics in a Classical Transmon Circuit

Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamics in a Classical Transmon Circuit Sasu Tuohino B. Sc. Thesis Department of Physical Sciences Theoretical Physics University of Oulu 2017 Contents 1 Introduction2 2 Classical network theory4 2.1 From electromagnetic fields to circuit elements.........4 2.2 Generalized flux and charge....................6 2.3 Node variables as degrees of freedom...............7 3 Hamiltonians for electric circuits8 3.1 LC Circuit and DC voltage source................8 3.2 Cooper-Pair Box.......................... 10 3.2.1 Josephson junction.................... 10 3.2.2 Dynamics of the Cooper-pair box............. 11 3.3 Transmon qubit.......................... 12 3.3.1 Cavity resonator...................... 12 3.3.2 Shunt capacitance CB .................. 12 3.3.3 Transmon Lagrangian................... 13 3.3.4 Matrix notation in the Legendre transformation..... 14 3.3.5 Hamiltonian of transmon................. 15 4 Classical dynamics of transmon qubit 16 4.1 Equations of motion for transmon................ 16 4.1.1 Relations with voltages.................. 17 4.1.2 Shunt resistances..................... 17 4.1.3 Linearized Josephson inductance............. 18 4.1.4 Relation with currents................... 18 4.2 Control and read-out signals................... 18 4.2.1 Transmission line model.................. 18 4.2.2 Equations of motion for coupled transmission line.... 20 4.3 Quantum notation......................... 22 5 Numerical solutions for equations of motion 23 5.1 Design parameters of the transmon................ 23 5.2 Resonance shift at nonlinear regime............... 24 6 Conclusions 27 1 Abstract The focus of this thesis is on classical dynamics of a transmon qubit. First we introduce the basic concepts of the classical circuit analysis and use this knowledge to derive the Lagrangians and Hamiltonians of an LC circuit, a Cooper-pair box, and ultimately we derive Hamiltonian for a transmon qubit. -

Advanced Quantum Theory AMATH473/673, PHYS454

Advanced Quantum Theory AMATH473/673, PHYS454 Achim Kempf Department of Applied Mathematics University of Waterloo Canada c Achim Kempf, September 2017 (Please do not copy: textbook in progress) 2 Contents 1 A brief history of quantum theory 9 1.1 The classical period . 9 1.2 Planck and the \Ultraviolet Catastrophe" . 9 1.3 Discovery of h ................................ 10 1.4 Mounting evidence for the fundamental importance of h . 11 1.5 The discovery of quantum theory . 11 1.6 Relativistic quantum mechanics . 13 1.7 Quantum field theory . 14 1.8 Beyond quantum field theory? . 16 1.9 Experiment and theory . 18 2 Classical mechanics in Hamiltonian form 21 2.1 Newton's laws for classical mechanics cannot be upgraded . 21 2.2 Levels of abstraction . 22 2.3 Classical mechanics in Hamiltonian formulation . 23 2.3.1 The energy function H contains all information . 23 2.3.2 The Poisson bracket . 25 2.3.3 The Hamilton equations . 27 2.3.4 Symmetries and Conservation laws . 29 2.3.5 A representation of the Poisson bracket . 31 2.4 Summary: The laws of classical mechanics . 32 2.5 Classical field theory . 33 3 Quantum mechanics in Hamiltonian form 35 3.1 Reconsidering the nature of observables . 36 3.2 The canonical commutation relations . 37 3.3 From the Hamiltonian to the equations of motion . 40 3.4 From the Hamiltonian to predictions of numbers . 44 3.4.1 Linear maps . 44 3.4.2 Choices of representation . 45 3.4.3 A matrix representation . 46 3 4 CONTENTS 3.4.4 Example: Solving the equations of motion for a free particle with matrix-valued functions . -

Perceived Reality, Quantum Mechanics, and Consciousness

7/28/2015 Cosmology About Contents Abstracting Processing Editorial Manuscript Submit Your Book/Journal the All & Indexing Charges Guidelines & Preparation Manuscript Sales Contact Journal Volumes Review Order from Amazon Order from Amazon Order from Amazon Order from Amazon Order from Amazon Cosmology, 2014, Vol. 18. 231-245 Cosmology.com, 2014 Perceived Reality, Quantum Mechanics, and Consciousness Subhash Kak1, Deepak Chopra2, and Menas Kafatos3 1Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078 2Chopra Foundation, 2013 Costa Del Mar Road, Carlsbad, CA 92009 3Chapman University, Orange, CA 92866 Abstract: Our sense of reality is different from its mathematical basis as given by physical theories. Although nature at its deepest level is quantum mechanical and nonlocal, it appears to our minds in everyday experience as local and classical. Since the same laws should govern all phenomena, we propose this difference in the nature of perceived reality is due to the principle of veiled nonlocality that is associated with consciousness. Veiled nonlocality allows consciousness to operate and present what we experience as objective reality. In other words, this principle allows us to consider consciousness indirectly, in terms of how consciousness operates. We consider different theoretical models commonly used in physics and neuroscience to describe veiled nonlocality. Furthermore, if consciousness as an entity leaves a physical trace, then laboratory searches for such a trace should be sought for in nonlocality, where probabilities do not conform to local expectations. Keywords: quantum physics, neuroscience, nonlocality, mental time travel, time Introduction Our perceived reality is classical, that is it consists of material objects and their fields. On the other hand, reality at the quantum level is different in as much as it is nonlocal, which implies that objects are superpositions of other entities and, therefore, their underlying structure is wave-like, that is it is smeared out. -

The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski: 1900–1935

The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski: 1900–1935 Paolo Mancosu Richard Zach Calixto Badesa The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski: 1900–1935 Paolo Mancosu (University of California, Berkeley) Richard Zach (University of Calgary) Calixto Badesa (Universitat de Barcelona) Final Draft—May 2004 To appear in: Leila Haaparanta, ed., The Development of Modern Logic. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004 Contents Contents i Introduction 1 1 Itinerary I: Metatheoretical Properties of Axiomatic Systems 3 1.1 Introduction . 3 1.2 Peano’s school on the logical structure of theories . 4 1.3 Hilbert on axiomatization . 8 1.4 Completeness and categoricity in the work of Veblen and Huntington . 10 1.5 Truth in a structure . 12 2 Itinerary II: Bertrand Russell’s Mathematical Logic 15 2.1 From the Paris congress to the Principles of Mathematics 1900–1903 . 15 2.2 Russell and Poincar´e on predicativity . 19 2.3 On Denoting . 21 2.4 Russell’s ramified type theory . 22 2.5 The logic of Principia ......................... 25 2.6 Further developments . 26 3 Itinerary III: Zermelo’s Axiomatization of Set Theory and Re- lated Foundational Issues 29 3.1 The debate on the axiom of choice . 29 3.2 Zermelo’s axiomatization of set theory . 32 3.3 The discussion on the notion of “definit” . 35 3.4 Metatheoretical studies of Zermelo’s axiomatization . 38 4 Itinerary IV: The Theory of Relatives and Lowenheim’s¨ Theorem 41 4.1 Theory of relatives and model theory . 41 4.2 The logic of relatives .