How to Construct an Authentic Ruff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRAND NAME PRODUCTS Branded Male Marketing to Men.Pdf

Branded Male hb aw:Branded Male 15/1/08 10:10 Page 1 BRANDED MALE Mark Tungate is the “Tungate dissects the social trends that have been shaping the male consumer across a Men are not what they were. In article after author of the variety of sectors in recent years… Provides insights on how brands can tackle the article we’re told a new type of man is bestselling Fashion business of engaging men in a relevant way – and the influential role that the women in abroad – he’s more interested in looking Brands, as well as the their lives play.” good and he’s a lot keener on shopping. highly acclaimed Carisa Bianchi, President, TBWA / Chiat / Day, Los Angeles Adland: A Global Branded Male sets out to discover what History of Advertising, “Finally a book that uses humour, examples and clever storytelling to shed a new light on makes men tick as consumers and how both published by male trends. Helps us approach male consumers as human beings and not simply as products and services are effectively Kogan Page. Based in marketing targets.” branded for the male market. Using a day Photography: Philippe Lemaire Paris, he is a journalist in the life of a fictional “branded male”, specializing in media, marketing and Roberto Passariello, Marketing Director, Eurosport International Mark Tungate looks at communication. Mark has a weekly column BRANDED male-orientated brands and their in the French media magazine Stratégies, “Ideas, advice and insights that will help anyone aiming to get messages across marketing strategies in areas as diverse as: and writes regularly about advertising, style to men.” and popular culture for the trends David Wilkins, Special Projects Officer, Men’s Health Forum • grooming and skincare; intelligence service WGSN and the • clothes; magazine Campaign. -

That Was a T-Shirt!!! We Need Tops! While Cotton Tops Are Easy to Make, Knit Tops Are the Most Versatile Due to the Forgiving Stretch

That was a t-shirt!!! We need tops! While cotton tops are easy to make, knit tops are the most versatile due to the forgiving stretch. Because of the challenges in working with knit fabric, updating a t-shirt is the perfect compromise. Our goal is to have someone look at our top and say “that was a t-shirt?!” All hemlines need to be removed and restyled and the neckline needs to be either ruffled (size small and some medium) or trimmed. Here are some guidelines that we are looking for. Simply sewing a decorative stitch or zigzag over the existing hemline (sleeves and bottom hem) does not make visual changes to the t-shirt. Please cut off the existing hemline and if you like, you can make it shorter. If you have a serger, you can finish the edge prior to hemming but because the knit does not ravel it is not necessary. You also do not need to turn over the edge prior to hemming. Sleeves Match the sleeves and cut off both hems at the same time. You can cut straight or at an angle and make it a cap sleeve Use a decorative stitch for the hemming, variegated thread looks great! Use either white or black thread in the bottom as variegated thread is expensive. Remember to sew on the right side with your finger on the bottom feeling for the fabric edge. Watch for those sales and coupons!! Sulky blendables, 30 weight, 100% cotton is very nice to use. If you hem with a straight stitch, make it a little longer perhaps 3.0 and add some elastic to make it gathered at the hem edge. -

Notions: Fabrics: Sewing with Cuddle™

Fabrics: Sewing with Cuddle™ Notions: 1/2 yard Daisy Bouquet Coral from These patterns are very easy to put Sewing machine Crazy for Daisies by ADORNit (dress) together and sew. Cuddle™ fabric Basic sewing supplies: 1/2 yard Mini Zag Aqua/Red/Breeze works best when you take care to pin Thread from Nested Owls by ADORNit each seam before sewing. You Ballpoint needle (sleeve and ruffle for pants) should be able to complete this Pins 3/4 yard Cuddle™ Dimple Teal (pants) project in under 3 hours! Scissors 1/4” elastic and 3/4” elastic 1 Cuddle™ Bouquet Peasant Dress and Ruffle Pants Below you will find a guide to tape your PDF printed pages together. When you print, make sure to select “actual size” so that your pattern does not print at the wrong scale. Check the 1 inch test box before cutting out your fabric to make sure everything is the right size! Read through each step before beginning your project! If there are any questions please contact me at [email protected] and I will be happy to help you! I drafted these patterns off of my daughter’s measurements. She wears a 24m/2T in ready to wear clothes. The dress is meant to be worn with the ruffle pants. If you prefer to have the dress worn alone, add 3-4 inches to the length. To print only the pattern pieces for the dress, print pages 12-15 To print only the pattern pieces for the pants, print pages 16-18 LEVEL—Beginner Terms of Use: Items made from this pattern may be used to sell in limited quantities. -

…Unruffled…Unruffled

TheThe RufflerRuffler …Unruffled…Unruffled A Guide to Buying, Optimizing, and Using a Ruffler Attachment Downloaded by: H C - 9/13/2008 - DUPLICATION PROHIBITED - Downloaded at www.youcanmakethis.com Table of Contents Introduction 3 • Purchasing a Ruffler 4 • Ruffler Anatomy 5 Using Your Ruffler 6 • Pre-Ruffling Checklist 6 • Attaching the Ruffler 7 • Getting to Know Your Ruffler 10 Optimizing Your Ruffler 11 • Ruffling Factor 11 • Testing Your Ruffler 11 • Ruffling Calculations 16 • Ruffling Double Thicknesses 17 • Pleats 18 Attaching Ruffles 19 • “Wiggle Room” 20 • One-Step Gathering and Attachment 21 • One-Step Gathering and Attachment II 22 • Ruffles & Ribbons 23 • Embellishing with Ruffles 24 Other Materials 25 The Dedicated Ruffler 25 Troubleshooting 26 Tools 27 • Ruffler Optimization Worksheet 27 • Ruffler Optimization Gauge 28 • Pleating/Ruffling Ruler 29 You Can Make This! 30 The Ruffler…Unruffled. Copyright © 2007 by Carla Hegeman Crim. All rights reserved. This guide is complimentary, and may be shared freely as long as this copyright statement stays intact. No part of this guide may be resold or redistributed by sites other than http://youcanmakethis.com without permission from the author. I am not affiliated with any doll, pattern, or sewing machine company. Disclaimer: This guide offers instructions and suggestions for normal use of a ruffler. I am not responsible for any ruffler-related injuries or damage to equipment. http://www.dressydolly.com Downloaded by: H C - 9/13/2008 - DUPLICATION PROHIBITED - Downloaded at www.youcanmakethis.com Introduction Ruffles, ruffles everywhere! In both fashion and home décor, nothing adds femininity and flounce like a beautiful ruffle. The ruffle is an important element of custom boutique fashion. -

Halloween Ruffled Edged Apron

Halloween Ruffled Edged Apron Use the Baby Lock Verve sewing and embroidery machine to add a ruffled to the bottom edge of a purchased apron. The edges are finished off using the Overcast “G” foot and a glow in the dark thread. Baking Halloween treats will never be this much fun! Skill Level: Beginner Created by: Diane Kron, Software and Embroidery Project Manager Baby Lock Project: Halloween Ruffled edge Apron Page 1 of 3 Supplies: Baby Lock® Verve Sewing and Embroidery Machine Purchased Apron 1 Fat quarter (Halloween print) Madeira® Glow in the Dark thread Madeira black Cotona thread White bobbin thread Black rick-rack Instructions: 1. At the cutting table, cut (4) 4 ½” wide strips from the Halloween print fabric. These sections will be used for the ruffle. When deciding on how long the ruffle should be, measure the area where it will be placed. The length of the unruffled section should be 2 to 3 times the length of the area. This will give a nice full ruffle. If your apron is larger than the one used in the sample, more fabric may be needed. 2. Set the machine up for sewing: Thread the machine with the Glow in the Dark thread. Wind the bobbin with white bobbin thread and place in the bobbin case. Select the Overcasting stitch #118. Snap on the Overcasting “G” Foot. 3. With right sides together, piece together the 4 ½” wide Halloween print sections end to end. 4. Overcast each of the seams together. Press the seams in the same directions. 5. Overcast the top and bottom edges on the pieced section along with each of the ends. -

Condensed Data Are Available in VT 002 611. a Wide Variety Of

I N Arti M I r% I T II E S V 14r ED 023 796 VT 002 621 By -0 Donnell.Beatrice Descriptions of Home and Community Occupations Related to Home Economics:Descriptions ofSpecific Occupations Classified Into Suc Clusters. Index to Areas of Work and Worker Trait Groupsfor Individual Occupateons.Professional Education Series No.HE -8. Michigan State Univ., East Lansing.Educational Publication Services. Pub Date Jan 67 Note -204p. EDRS Price MI -SI 00 HC -51030 . Descriptors -.Home EconomicsSkills,*Occupational Clusters. Occupational Guidance, Occupational Home Economics. *Occupational Information. Occupations Identifiers -Dictionary of Occupational Titles This buletin is a relerence tool for the identification of homeeconomics-related occupations and requirements and methodsof entry into these occupations. A full description of 200 home econor,:s-related occupations as found inthe Dictionary of Occupational Titles. Volume I, and page references which will facilitate thelocation of descriptions of the "area of work" and "worker trait group" asindicated in Volume H of the Dictionary are presented. Occupations have been classified andalphabetically arranged into one of six clusters: (1) family relationships. (2) clothing andtextiles, (3) foods and nutrition, (4) housing and furnishings, (5) clothing maintenance,and (6) household maintenance and services. Home economics-related occupations were identified by independent analysisof thethirdedition of the Dictionary of Occupational Titles, Volume I. Lists were compared and organized intoclusters. Value judgments of 136 knowledgeable persons to the questions: (1)Is the occupation related to the duster in which it is dassified? (2) To what extent is home economics needed for job competence or lob training? and (3) What otherprofessional.business. -

Page 1 the Nature of Luxury 3

DEFINING LUXURY WHAT MAKES AN EXPERIENCE BETTER The Nature of Luxury 3 DEFINING LUXURY hat is luxury? In the highest form, luxury is a thing W of well-crafted beauty that combines dynamic performance with precision engineering. Luxury is also something that enriches your life, that saves you time, that makes your life more effortless. Luxury means creating experiences that are human, personalized, inspired and innovative. And when all of these attributes synthesize organically, the result is breathtaking, leaving us feeling effortlessly in control. That is the goal. Get ready to experience the 2017 Lincoln Continental. CHAPTERS 3 Exquisite Craftsmanship Andy Mooney, the CEO of Fender, on how craftsmanship influences the songs that come from within their guitars; reinventing craftsmanship around the globe; exquisitely cut gems that inspire works of art. 9 Dynamic Performance Kelly Slater, pro surfer and founder of Outerknown clothing, on the physical zen that defines a good surfing experience; the soaring future of aviation; the effortless sport of crew, deconstructed. 17 Exclusive Experience Geoffrey Kent, founder and CEO of Abercrombie & Kent, on the qualities that create an incredible travel experience; how a great mixologist can intuit your tastes; the modern era of members clubs. 23 Precision Engineering Margot Lee Shetterly, author of Hidden Figures, on which the landmark film is based, celebrates the unsung heroines of the American space program; engineering meets art in contemporary bridge design; the science of sound. 30 The Road to Serenity Author and columnist Stanley Bing experiences firsthand what occurs when the four Published by The Foundry at Time Inc. for the Lincoln Motor Company | thefoundry.nyc pillars of luxury converge, as he test-drives the 2017 Lincoln Continental. -

Ruffle Sleeve Top Issue 37

RUFFLE SLEEVE TOP ISSUE 37 SKILL LEVEL In the Folds patterns are designed to inspire and encourage modern makers to create garments that are beautiful both inside ABOUT CONTENTS and out. Through selected techniques and construction details, IN THE In the Folds aims to encourage thought-provoking and ABOUT IN THE FOLDS 3 memorable making experiences - helping you enjoy each stitch in PATTERNS FOLDS the process. PATTERNS GARMENT OVERVIEW 4 Techniques may differ slightly to the home sewing methods you (INCLUDING FABRIC SUGGESTIONS AND NOTIONS) are used to, but in some cases industrial finishes will give you the cleanest and most professional finish. SIZING + GARMENT 5 MEASUREMENTS Seam allowances are marked on each pattern piece and detailed (INCLUDING FABRIC REQUIREMENTS) in each step. You will notice that in some cases the seam allowances meet each PRINTING THE PATTERN 6 other at different angles at the end of the seam. This is so that PRINTING PLAN 7 when you press the seam allowances open the seams will sit flush with the edges and will help you get a really clean finish. CUTTING YOUR FABRIC 8 In the Folds patterns are designed to include thoughtful Consider using fabric SUGGESTED CUTTING PLAN 9 details and interesting techniques so that you can enjoy the from your stash before process of making the garment as much as the end result. going to buy something INSTRUCTIONS 10 new. I dare you. If we slow down and take in every stitch, we can better You might be surprised GLOSSARY 21 our skills, appreciate the amazing things we can do with by what you find there. -

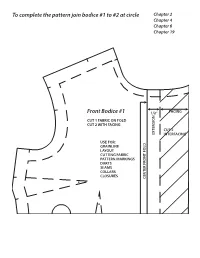

To Complete the Pattern Join Bodice #1 to #2 at Circle Front Bodice #1

To complete the pattern join bodice #1 to #2 at circle Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 19 Front Bodice #1 1/2” FACING N CUT 1 FABRIC ON FOLD CUT 2 WITH FACING CUT 2 EXTENSIO INTERFACING USE FOR: GRAINLINE LAYOUT CUTTING FABRIC PATTERN MARKINGS DARTS SEAMS COLLARS CLOSURES CENTER FRONT FOLD To completeTo the pattern join bodice #1 to #2 at circle TO COMPLETE THE PATTERN JOIN BODICE #1 TO #2 AT CIRCLE STITCH TO MATCHPOINTS FOR DART TUCK FRONT BODICE #2 Front Bodice #2 Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 19 STITCH TO MATCHPOINTS FOR DART TUCKS To complete the pattern join bodice #3 to #4 at circle Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Back Bodice #3 CUT 2 FABRIC USE FOR: CK SEAM GRAINLINE LAYOUT CUTTING FABRIC CK FOLD PATTERN MARKINGS DARTS SEAMS COLLARS CENTER BA CUT HERE FOR CENTER BA To completeTo the pattern join bodice #3 to #4 at circle STITCH TO MATCHPOINTS FOR DART TUCKS Back Bodice #4 Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 4 Chapter 11 Chapter 14 Chapter 17 MATCHPOINT Front Skirt #5 CUT 1 FABRIC USE FOR: V SHAPED SEAM WAISTBAND WAIST FACING BIAS WAIST FINISH CURVED/ALINE HEM BIAS FALSE HEM CENTER FRONT FOLD Chapter 4 Chapter 11 Chapter 14 Front Yoke #6 CUT 1 FABRIC CUT 1 INTERFACING USE FOR: V SHAPE SEAM WAISTBAND WAIST FACING BIAS WAIST FINISH C. F. FOLD C. F. MATCHPOINT Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 14 Chapter 17 MARK DART POINT HERE Back Skirt #7 CUT 2 FABRIC USE FOR: SEAMS ZIPPERS WAISTBAND WAIST FACING BIAS WAIST FINISH CURVED ALINE HEM BIAS FALSE HEM Chapter 4 CUT ON FOLD Chapter 12 Chapter 17 H TC NO WHEN -

Bella Morocco Runner Created by Susan Fears

Bella Morocco Runner Created by Susan Fears Combine the powerful and creative features of the BERNINA 780 with the Bella Morocco BERNINA Embroidery Collection to create a fantastic runner—for the table, or the bed. Vary the size just by adding or subtracting fabric strips or embroidery combinations. Finished Dimensions: approx 21” x 57” Supplies Machine & Accessories Green Fabric for edge ruffle & strips, approx ¾ yd BERNINA 780/830 Sewing & Embroidery Machine 1¼ yards backing fabric Oval Hoop Ultra Clean and Tearaway Stabilizer 10” & 15” Mega Hoop (optional) Fuse and Fleece, 10” & 15” Jumbo Hoop Warm & Natural Batting, 22” x 47” Teardrop Embroidery Foot #26 Organ Embroidery Needles, Size 80 Dual Feed Patchwork Foot w/Guide #57D Piecing & General Construction Needle, Universal #90 Dual Feed Patchwork Foot #37D Quilting Needle, Size 90 Dual Feed Edgestitch Foot #10D Master Hooper All-Purpose Dual Feed Foot #1D Threads BERNINA Stitch Regulator #42 Isacord embroidery thread to coordinate with fabrics Embroidery Design Collection (4410, 4032, 4421, 5722, 6141, 4620, 0761, 1874) BERNINA Exclusive Embroidery Collection - Bottom Line Neutral Embroidery Bobbin thread Bella Morocco #82005 Aurifil Cotton 50/2 Thread for decorative stitching & Fabric & Notions Free Motion Quilting (Color 2830) Mettler 50 weight thread for piecing & construction 3-4 Fat Quarters—Cream Fabrics in varying shades Variety of Blue, Green & Brown Fabrics in varying shades totaling, approx 1– 1½ yds (6 fabrics used in sample Visit bernina.com Projects ● Webinars ● Promotions ©2013 BERNINA of America, Inc. Page 1 of 8 Runner Diagram Diagram shows the layout from the center to one end; repeat the layout on the other side of the center to complete the runner. -

Almost Amish Apron, Children's Size

Almost Amish Apron, Children’s Size 7 ½” Selvages 1/2” Pocket 7 ½ ” Ruffle Ruffle Tie (makes 2) 17” waistband Body of Apron (cut 1) 11 ” Fold 3 ¾” 3 ¾” 3 ¾ ” 4 ½ ” 13” 1/2 yd red fabric for ruffles, ties, waistband, and pocket 3/8 yd floral fabric for body of apron (makes 2) 1. Make ties by sewing right sides together then turning right side out. 2. Form ruffle by sewing two pieces together to form one long piece, fold in half length-wise with wrong sides together, run gathering stitch (long machine stitch) with raw edges together. 3. Apply ruffle to side and bottom edges of apron, gathering up the ruffle to fit and discarding extra ruffle. 4. Prepare pocket and topstitch onto apron. Sew on button. 5. With right sides together stitch waistband to top edge of apron, folding ends of waistband under to be even with edge of ruffle. Fold waistband to inside and pin barely over seam. On right side of apron, topstitch waistband near seam line. 6. Insert ties into ends of waistband and stitch across. Almost Amish Apron, Detailed Instructions 1. Fabric amounts and cutting of pieces are shown below. 9” Selvages Pocket 9” Ruffle Ruffle Tie Tie 22” waistband Body of Apron (cut 1) 13 ¼” Fold 4” 4” 4 ¾ ” 4 ¾ ” 5” 19” 3/4 yd red fabric for ruffles, ties, waistband, and pocket 5/8 yd floral fabric for body of apron 2. Fold tie in half length-wise right sides together and press. Stitch long edge and one short edge 1/2” from raw edge. -

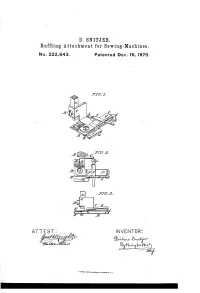

Ruffling Attachment for Sewing-Machines, No

D, SNITJER, Ruffling Attachment for Sewing-Machines, No. 222,643. Patented Dec. 16, 1879. UNITED STATES PATENT DRIKUS SNITJER, OF ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI, ASSIGNOR OF ONE-HALF OF HIS RIGHT TO THE SINGER MANUFACTURING COMPANY. MPROVEMENT IN RUFFLING ATTACHMENTS FOR SEWING-MACH NES, Specification forming part of Letters Patent No. 222,643, dated December 16, 1879; application filed December 17, 1878. To all whom it may concern: ing puckered by the tightening of the stitch. Be it known that I, DRIKUS SNITJER, of This is a matter of importance both on the the city of St. Louis, in the State of Missouri, score of appearance and strength. - have invented a certain new and useful Im The tongue H, by pressure of the ruffle upon provement in Ruffling Attachments for Sew the feed-dog behind the needle, enables the ing-Machines, of which the following is a full, feed-dog to pull the work along behind the clear, and exact description, reference being needle and to draw the band along from un had to the accompanying drawings, forming der the Spring-plate F by means of the seam part of this specification. connection. - My improvement relates to that class of In the absence of the tongue H, when the rufflers in which the pressure upon the ruffie stitch is tightened, the band is drawn a little piece is not received through the band-strip. at each stitch and becomes puckered, and the In the drawings, Figure 1 is an isometric appearance is bad. view of my ruffler. Fig. 2 is a top view, and When the band is puckered the whole strain Fig.