Galápagos Land Iguana (Conolophus Subcristatus) As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relationships Among Native and Alien Plants on Pacific Islands with and Without Significant Human Disturbance and Feral Ungulates

RELATIONSHIPS AMONG NATIVE AND ALIEN PLANTS ON PACIFIC ISLANDS WITH AND WITHOUT SIGNIFICANT HUMAN DISTURBANCE AND FERAL UNGULATES Mark D. Merlin and James 0. Juvik ABSTRACT The native plants of remote tropical islands have been frequently characterized as poor competitors against seemingly more aggressive alien species.. Does this "weak competitor" characterization relate to some real adaptive consequences of island isolation and endemism, or does the generally concurrent presence of introduced ungulates and other forms of recurrent human disturbance also act to encourage alien plant dominance? A comparison of tropical islands with and without introduced ungulates suggests that some insular plant species competitively resist alien displacement in the absence of ungulates. INTRODUCTION For millions of years remote tropical islands in the Pacific Ocean have provided a variety of ecological opportunities for plant species that reached them through long-distance dispersal mechanisms. Many species that successfully established themselves on far-flung oceanic islands gave rise to extraordinary endemic forms, examples of adaptive radiation, and unusual adaptive shifts. Evolutionary developments occurred on isolated islands largely because of the limited numbers and kinds of colonizing taxa and varying environmental diversity within islands or groups of islands. Among the structural and physiological adaptations that frequently occur in remote island environments is the disappearance of typical defensive mechanisms such as poisons, strong odors, thorns, deep tap roots, and tough stems and branches in insular plant species. Some of these adaptations left many species especially vulnerable to a variety of alien ungulates introduced in the historic period (Fosberg 1965; Mangenot 1965; Mueller-Dombois 1975). In the Hawaiian Islands, for example, only a very small fraction of the endemic species of plants produce poisons, thorns, or other defensive strategies against herbivory (Carlquist 1974, 1980). -

„Fernandina“ – Itinerary

Beluga: „Fernandina“ – Itinerary This itinerary focuses on the Central and Western Islands, including visits to Western Isabela and Ferndina Island, two of the highlights of the Galapagos Islands. Day 1 (Friday): Arrive at Baltra Airport / Santa Cruz Island Santa Cruz Island • Highlands of Santa Cruz: Galapagos giant tortoises can be seen in the wild in the highlands of Santa Cruz • Charles Darwin Station: Visit the Charles Darwin Station is a research facility and National Park Information center. The Charles Darwin Station has a giant tortoise and land iguana breeding program and interpretation center. Day 2 (Saturday): Floreana Island Floreana Island: Floreana is best known for its colorful history of buccaneers, whalers, convicts, and early colonists. • Punta Cormorant: Punta Cormorant has two contrasting beaches and a large inland lagoon where pink flamingoes can be seen. • Devil’s Crown: This is a snorkeling site located just off Punta Cormorant. The site is a completely submerged volcano that has eroded to create the appearance of a jagged crown. • Post Office Bay: This is one of the few sites visited for its human history. Visit the wooden mail barrel where letters are dropped off and picked up and remains of the Norwegian fishing village. Day 3 (Sunday): Isabela Island Isabela Island (Albemarle): Isabela is the largest of the Galapagos Islands formed by five active volcanoes fused together. Wolf Volcano is the highest point in the entire Galapagos at 1707m. • Sierra Negra : Volcan Sierra Negra has a caldera with a diameter of 10km. View recent lava flows, moist highland vegetation, and parasitic cones. • Puerto Villamil: Puerto Villamil is a charming small town on a white sand beach. -

Cyclura Or Rock Iguanas Cyclura Spp

Cyclura or Rock Iguanas Cyclura spp. There are 8 species and 16 subspecies of Cyclura that are thought to exist today. All Cyclura species are endangered and are listed as CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) Appendix I, the highest level of pro- tection the Convention gives. Wild Cyclura are only found in the Caribbean, with many subspecies endemic to only one particular island in the West Indies. Cyclura mature and grow slowly compared to other lizards in the family Iguani- dae, and have a very long life span (sometimes reaches ages of 50+ years). The more common species in the pet trade in- clude the Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta cornuta), and Cuban Rock Iguana (juvenile), the Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila nubila). Cyclura nubila nubila Basic Care: Habitat: Cyclura care is similar to that of the Green Iguana (Iguana iguana), but there are some major differences. Cyclura Iguanas are generally ground-dwelling lizards, and require a very large cage with lots of floor space. The suggested minimum space to keep one or two adult Cyclura in captivity is usually a cage that is at the very least 10’X10’. Because of this space requirement, many cyclura owners choose to simply des- ignate a room of their home to free-roaming. If a male/female pair are to be kept to- gether, multiple basking spots, feeding stations, and hides will be required. All Cyclura are extremely territorial and can inflict serious injuries or even death to their cage- mates unless monitored carefully. The recommended temperature for Cyclura is a basking spot of about 95-100F during the day, with a temperature gradient of cooler areas to escape the heat. -

Sesuvium Portulacastrum (L.) L

Sesuvium portulacastrum (L.) L. Sea Purslane (Portulaca portulacastrum) Other Common Names: Cenicilla, Shoreline Sea Purslane, Shoreline Purslane. Family: Aizoaceae, subfamily Sesuvioideae. Cold Hardiness: Not well documented, but plants are winter hardy in USDA zones 9(8b) to 13, with shoots damaged by temperatures below the upper to mid-20°F, while established root systems may survive in mulched or sheltered locations in warmer parts of USDA zone 8b. Foliage: Evergreen, alternate, simple succulent leaves are up to about 2 long and more or less cylindrical or flattened oblong to narrowly oblanceolate, tapering to point; bases tend to clasp the stems; foliage is generally reminiscent of a robust coarse textured moss rose (Portulaca grandiflora); in cool weather or when plants are under stress, the foliage takes on a reddish cast, but is otherwise a strong dark green color. Flower: Small ¾diameter solitary star-shaped flowers are borne on ¼ long peduncles in the axils of the leaves; showy portions of the flowers are the white, pinkish purple to pale purple, or bicolor interior of the sepals; numerous stamens surround a single pistil; flowers occur whenever temperature conditions permit, but are small and scattered in the canopy minimizing their aesthetic contributions. Fruit: Aesthetically inconsequential small ¼ long conical capsules develop with tiny smooth shiny black seeds that are shaken out by the wind after the lid-like top of the capsule matures and is lost. Stem / Bark: Stems — stems are snaky, long, rope-like, and mostly prostrate or pendent, although some genotypes are erect for brief periods of time prior to being weighted down to the ground as they grow; stems are thickened and succulent, nearly round in cross-section and light green, green, or reddish on new stems, these typically mature to a dark green as stems age; Buds — the tiny, foliose buds do not develop bud scales; buds are usually a similar color as the stems; Bark — not applicable. -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

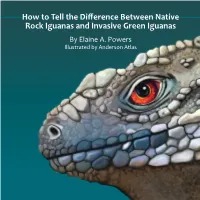

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Distribution and Current Status of Rodents in the Galapagos

April 1994 NOTICIAS DE GALÁPAGOS 2I DISTRIBUTION AND CURRENT STATUS OF RODENTS IN THE GALÁPAGOS By: Gillian Key and Edgar Muñoz Heredia. INTRODUCTION (GPNS) and the Charles Darwin Resea¡ch Station (CDRS) in their continuing efforts to protecr the The uniqueness and scientific importance of the unique wildlife of the islands. Galápagos Islands has longbeenrecognized, although the c¡eation of the National Park in 1959 came after ENDEMIC RODENTS several centuries of sporadic use and colonization by man. Undoubtedly, the lack of water in the islands Seven species of endemicricerats a¡eknown from has been thei¡ savior by limiting the extent and dura- the Archipelago, of which the seventh was only rel- tion of many early attempts to colonize. Even so the atively recently discove¡ed from owl pellets on impact of man has been severe in the Archipelago, Fernandina island (Ilutterer & Hirsch 1979), Brosset and the biggest problems for conservation today are ( 1 963 ) and Niethammer ( 1 9 64) have summarized the the introduced species of plants and animals. These available information on the six species known at introduced species are frequently pests to the human that time, including last sightings and probable dates inhabitants as well as to the native flora and fauna, to ofextinction. Galápagosricerats belongto twoclosely the former by damaging crops and goods, and to the related generaof oryzomys rodents and were distrib- latter by competition, predation and transmission of uted among the six islands (Table 1). disease. Patton and Hafner (1983) concluded that rats of The feral mammals in particular constitute a ma- the genus Nesoryzomys arrived in the Archipelago jorproblem, principally due to their size and numbers. -

Dietary Purslane (Portulaca Oleracea L.) Promotes the Growth Performance of Broilers by Modulation of Gut Microbiota

Wang et al. AMB Expr (2021) 11:31 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-021-01190-z ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Dietary purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) promotes the growth performance of broilers by modulation of gut microbiota Cong Wang1, Qing Liu1,2, Fengchun Ye3, Hongbo Tang1, Yanpeng Xiong1, Yongfei Wu1, Luping Wang1, Xuanbiao Feng1, Shuiyin Zhang1,2, Yongmei Wan1 and Jianhua Huang1,2* Abstract Purslane is a widespread wild vegetable with both medicinal and edible properties. It is highly appreciated for its high nutritional value and is also considered as a high-quality feed resource for livestock and poultry. In this study, Sanhuang broilers were used to investigate the efect of feeding purslane diets on the growth performance in broil- ers and their gut microbiota. A total of 48 birds with good growth and uniform weight were selected and randomly allocated to four treatment groups A (control), B, C and D. Dietary treatments were fed with basal diet without purslane and diets containing 1%, 2% and 3% purslane. The 16S rDNA was amplifed by PCR and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq platform to analyze the composition and diversity of gut microbiota in the four sets of samples. The results showed that dietary inclusion of 2% and 3% purslane could signifcantly improve the growth performance and reduce the feed conversion ratio. Microbial diversity analysis indicated that the composition of gut microbiota of San- huang broilers mainly included Gallibacterium, Bacteroides and Escherichia-Shigella, etc. As the content of purslane was increased, the abundance of Lactobacillus increased signifcantly, and Escherichia-Shigella decreased. LEfSe analysis revealed that Bacteroides_caecigallinarum, Lachnospiraceae, Lactobacillales and Firmicutes had signifcant diferences compared with the control group. -

Suggested Guidelines for Reptiles and Amphibians Used in Outreach

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS USED IN OUTREACH PROGRAMS Compiled by Diane Barber, Fort Worth Zoo Originally posted September 2003; updated February 2008 INTRODUCTION This document has been created by the AZA Reptile and Amphibian Taxon Advisory Groups to be used as a resource to aid in the development of institutional outreach programs. Within this document are lists of species that are commonly used in reptile and amphibian outreach programs. With over 12,700 species of reptiles and amphibians in existence today, it is obvious that there are numerous combinations of species that could be safely used in outreach programs. It is not the intent of these Taxon Advisory Groups to produce an all-inclusive or restrictive list of species to be used in outreach. Rather, these lists are intended for use as a resource and are some of the more common species that have been safely used in outreach programs. A few species listed as potential outreach animals have been earmarked as controversial by TAG members for various reasons. In each case, we have made an effort to explain debatable issues, enabling staff members to make informed decisions as to whether or not each animal is appropriate for their situation and the messages they wish to convey. It is hoped that during the species selection process for outreach programs, educators, collection managers, and other zoo staff work together, using TAG Outreach Guidelines, TAG Regional Collection Plans, and Institutional Collection Plans as tools. It is well understood that space in zoos is limited and it is important that outreach animals are included in institutional collection plans and incorporated into conservation programs when feasible. -

Introduction Itinerary

GALAPAGOS ISLANDS - ALYA | 6 DAY WESTERN ISLANDS TRIP CODE ECGSA6 DEPARTURE Select Mondays DURATION 6 Days LOCATIONS Galapagos Islands: Santa Cruz, Isabela, Fernandina and Santiago Islands INTRODUCTION GREAT CHIMU SALE EXCLUSIVE: Book and Save up to 33%* off select Departures Explore the Western islands of the Galapagos on this 6 Day Cruise. On board the luxury Alya catamaran you will find a unique blend of high service and comfortable modernity that makes cruising through the Galapagos an unbeatable experience. Within 6 Days you will explore 4 unique islands and smaller islets each extremely different from the last. On the shores of Bachas beach you will find the remnants of WWII US ships, in the highlands of Santa Cruz you may encounter roaming giant tortoises, at Urbina Bay you will witness large colonies of marine iguanas. Each experience in the Galapagos is entirely unique. The Alya Experience The Alya is designed to get the most out of your experience. Launched in 2017, this superior first-class motor catamaran offers comfort and luxury. This is the wonderful vessel to cruise the Galapagos. The ship offers 9 comfortable cabins, all tastefully decorated and featuring private facilities. The catamaran sails with a crew of 8 plus a bilingual, certified naturalist guide ensuring you get the most out of your time onboard the Alya and in the Galapagos. You have the opportunity to explore the Galapagos archipelago with activities such as hiking, snorkelling and kayaking. The cruise can provide you with a comfortable retreat after adventure-packed days of exploration. While sailing the pristine waters you can relax onboard and enjoy the panoramic views from the comfort of the ship. -

CARE of the GREEN IGUANA

Client Education—Green Iguana CARE of the GREEN IGUANA Iguanas in the Wild The green or common iguana (Iguana iguana) is a tree-dwelling reptile native to the tropical and subtropical regions of central and South America and parts of Mexico. The iguana is a solitary creature. Soon after hatching, the young go off to live alone. Iguanas come together only during the breeding season. The green iguana is a strict vegetarian, feeding primarily on vines, stems, leaves and flowers. The iguana also has a good sense of sight, smell and hearing. It tends to be a wary creature and will hide or flee at the first sign of danger. During the day, iguanas bask on tree branches that hang over the water. When threatened or frightened, the iguana will drop into the water or the ground below. Keeping a Pet Iguana Unlike domestic pets that have lived with human beings for multiple generations, pet reptiles, (even those that are captive bred) are still essentially wild animals. Our goal for keeping iguanas in captivity should be to copy their natural environment and diet as closely as possible. With proper care, iguanas can live for up to 12 to 15 years and reach six feet in length. Your Iguana’s Environment Iguanas are asocial, territorial animals and should be housed singularly. Young iguanas may seem to coexist well at first, but problems soon arise since the larger, more aggressive iguana will physically intimidate its cage mates and monopolize food and heat sources. Iguanas, particularly those less than 2 years of age, should be confined to their enclosure. -

Chassahowitzka Chassahowitzka Plan Comprehensive Conservation

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Chassahowitzka NationalWildlifeRefuge Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge Refuge Manager: Michael Lusk, (Project Leader) 1502 S.E. Kings Bay Drive Crystal River, FL 34429 Phone: (352) 563-2088 / ext. 202 Fax: (352) 795-7961 E-mail: [email protected] U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 1 800/344 WILD http://www.fws.gov Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive ConservationPlan September 2012 Comprehensive Conservation Plan USFWS Photos Photo Credits: Operation Migration, by Keith Ramos Dog Island, by Amber Breland Chass Aerial, by Joyce Kleen Comprehensive Conservation Plans provide long-term guidance for manage- ment decisions; set forth goals, objectives, and strategies needed to accom- plish refuge purposes; and identify the Fish and Wildlife Service’s best esti- mate of future needs. These plans detail program planning levels that are sometimes substantially above current budget allocations and, as such, are primarily for Service strategic planning and program prioritization purposes. The plans do not constitute a commitment for staffing increases, operational and maintenance increases, or funding for future land acquisition. Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region September 2012 COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN CHASSAHOWITZKA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Citrus and Hernando Counties, Florida U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia September