Black Panther Transmedia: the Revolution Will Not Be Streamed Niels Niessen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2014 Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College Recommended Citation Hernandez, Dahnya Nicole, "Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960" (2014). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 60. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/60 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUNNY PAGES COMIC STRIPS AND THE AMERICAN FAMILY, 1930-1960 BY DAHNYA HERNANDEZ-ROACH SUBMITTED TO PITZER COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE FIRST READER: PROFESSOR BILL ANTHES SECOND READER: PROFESSOR MATTHEW DELMONT APRIL 25, 2014 0 Table of Contents Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................................................2 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................3 Chapter One: Blondie.....................................................................................................................................18 Chapter Two: Little Orphan Annie............................................................................................................35 -

Williams, Hipness, Hybridity, and Neo-Bohemian Hip-Hop

HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Maxwell Lewis Williams August 2020 © 2020 Maxwell Lewis Williams HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Maxwell Lewis Williams Cornell University 2020 This dissertation theorizes a contemporary hip-hop genre that I call “neo-bohemian,” typified by rapper Kendrick Lamar and his collective, Black Hippy. I argue that, by reclaiming the origins of hipness as a set of hybridizing Black cultural responses to the experience of modernity, neo- bohemian rappers imagine and live out liberating ways of being beyond the West’s objectification and dehumanization of Blackness. In turn, I situate neo-bohemian hip-hop within a history of Black musical expression in the United States, Senegal, Mali, and South Africa to locate an “aesthetics of existence” in the African diaspora. By centering this aesthetics as a unifying component of these musical practices, I challenge top-down models of essential diasporic interconnection. Instead, I present diaspora as emerging primarily through comparable responses to experiences of paradigmatic racial violence, through which to imagine radical alternatives to our anti-Black global society. Overall, by rethinking the heuristic value of hipness as a musical and lived Black aesthetic, the project develops an innovative method for connecting the aesthetic and the social in music studies and Black studies, while offering original historical and musicological insights into Black metaphysics and studies of the African diaspora. -

Captain America

TIMELY COMICS MARCH 1941 CAPTAIN AMERICA Captain America is a fictional character that appears in comic books published by Marvel Comics. Early Years and WWII Steve Rogers was a scrawny fine arts student specializing in industrialization in the 1940's before America entered World War II. He attempted to enlist in the army only to be turned away due to his poor constitution. A U.S. officer offered Rogers an alternative way to serve his country by being a test subject in project, Operation: Rebirth, a top secret defense research project designed to create physically superior soldiers. Rogers accepted and after a rigorous physical and combat training and selection process was selected as the first test subject. He was given injections and oral ingestion of the formula dubbed the "Super Soldier Serum" developed by the scientist Dr. Abraham Erskine. Rogers was then exposed to a controlled burst of "Vita-Rays" that activated and stabilized the chemicals in The Golden Age of Comics his system. The process successfully altered his physiology from its frail state The Golden Age of Comic Books among them Superman, Batman, to the maximum of human efficiency, was a period in the history of Captain America, and Wonder including greatly enhanced musculature American comic books, generally Woman. and reflexes. After the assassination of Dr. thought of as lasting from the late Erskine. Roger was re-imagined as a The period saw the arrival of the 1930s until the late 1940s. During superhero who served both as a counter- comic book as a mainstream art intelligence agent and a propaganda this time, modern comic books form, and the defining of the symbol to counter Nazi Germany's head of were first published and enjoyed a medium's artistic vocabulary and terrorist operations, the Red Skull. -

Avengers and Its Applicability in the Swedish EFL-Classroom

Master’s Thesis Avenging the Anthropocene Green philosophy of heroes and villains in the motion picture tetralogy The Avengers and its applicability in the Swedish EFL-classroom Author: Jens Vang Supervisor: Anne Holm Examiner: Anna Thyberg Date: Spring 2019 Subject: English Level: Advanced Course code: 4ENÄ2E 2 Abstract This essay investigates the ecological values present in antagonists and protagonists in the narrative revolving the Avengers of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The analysis concludes that biocentric ideals primarily are embodied by the main antagonist of the film series, whereas the protagonists mainly represent anthropocentric perspectives. Since there is a continuum between these two ideals some variations were found within the characters themselves, but philosophical conflicts related to the environment were also found within the group of the Avengers. Excerpts from the films of the study can thus be used to discuss and highlight complex ecological issues within the EFL-classroom. Keywords Ecocriticism, anthropocentrism, biocentrism, ecology, environmentalism, film, EFL, upper secondary school, Avengers, Marvel Cinematic Universe Thanks Throughout my studies at the Linneaus University of Vaxjo I have become acquainted with an incalculable number of teachers and peers whom I sincerely wish to thank gratefully. However, there are three individuals especially vital for me finally concluding my studies: My dear mother; my highly supportive girlfriend, Jenniefer; and my beloved daughter, Evie. i Vang ii Contents 1 Introduction -

Captain America and the Struggle of the Superhero This Page Intentionally Left Blank Captain America and the Struggle of the Superhero Critical Essays

Captain America and the Struggle of the Superhero This page intentionally left blank Captain America and the Struggle of the Superhero Critical Essays Edited by ROBERT G. WEINER Foreword by JOHN SHELTON LAWRENCE Afterword by J.M. DEMATTEIS McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London ALSO BY ROBERT G. WEINER Marvel Graphic Novels and Related Publications: An Annotated Guide to Comics, Prose Novels, Children’s Books, Articles, Criticism and Reference Works, 1965–2005 (McFarland, 2008) LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Captain America and the struggle of the superhero : critical essays / edited by Robert G. Weiner ; foreword by John Shelton Lawrence ; afterword by J.M. DeMatteis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3703-0 softcover : 50# alkaline paper ¡. America, Captain (Fictitious character) I. Weiner, Robert G., 1966– PN6728.C35C37 2009 741.5'973—dc22 2009000604 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2009 Robert G. Weiner. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover images ©2009 Shutterstock Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 6¡¡, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Dedicated to My parents (thanks for your love, and for putting up with me), and Larry and Vicki Weiner (thanks for your love, and I wish you all the happiness in the world). JLF, TAG, DW, SCD, “Lizzie” F, C Joyce M, and AH (thanks for your friend- ship, and for being there). -

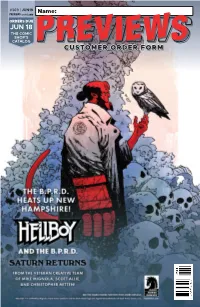

Jun 18 Customer Order Form

#369 | JUN19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE JUN 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Jun19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:08:57 PM June19 Humanoids Ad.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:15:02 PM SPAWN #300 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN/SUPERMAN #1 DC COMICS COFFIN BOUND #1 GLOW VERSUS IMAGE COMICS THE STAR PRIMAS TP IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN VS. RA’S AL GHUL #1 DC COMICS BERSERKER UNBOUND #1 DARK HORSE COMICS THE DEATH-DEFYING DEVIL #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS #1000 MARVEL COMICS HELLBOY AND THE B.P.R.D.: SATURN RETURNS #1 ONCE & FUTURE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS Jun19 Gem Page.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:24:56 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Bad Reception #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Flash: Crossover Crisis Book 1: Green Arrow’s Perfect Shot HC l AMULET BOOKS Archie: The Married Life 10 Years Later #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Warrior Nun: Dora #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars: Rey and Pals HC l CHRONICLE BOOKS 1 Lady Death Masterpieces: The Art of Lady Death HC l COFFIN COMICS 1 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons l DISNEY EDITIONS Moomin: The Lars Jansson Edition Deluxe Slipcase l DRAWN & QUARTERLY The Poe Clan Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Cycle of the Werewolf SC l GALLERY 13 Ranx HC l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Superman and Wonder Woman With Collectibles HC l HERO COLLECTOR Omni #1 l HUMANOIDS The Black Mage GN l ONI PRESS The Rot Volume 1 TP l SOURCE POINT PRESS Snowpiercer Hc Vol 04 Extinction l TITAN COMICS Lenore #1 l TITAN COMICS Disney’s The Lion King: The Official Movie Special l TITAN COMICS The Art and Making of The Expance HC l TITAN BOOKS Doctor Mirage #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT The Mall #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 2 World’s End Harem: Fantasia Volume 1 GN l GHOST SHIP My Hero Academia Smash! Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Kingdom Hearts: Re:Coded SC l YEN ON Overlord a la Carte Volume 1 GN l YEN PRESS Arifureta: Commonplace to the World’s Strongest Zero Vol. -

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

B E N N I N G T O N W R I T I N G S E M I N A

MFAW PUBLIC SCHEDULE June 15–24, 2017 NOTE: Schedule subject to change All faculty, guest, and graduate lectures and readings will be held in Tishman Lecture Hall, unless otherwise indicated. All evening Faculty and Guest Readings will be held in the Deane Carriage Barn. Thursday, June 15 7:00 Faculty & Guest Readings: Kaitlyn Greenidge and Amy Hempel Friday, June 16 Graduate Readings 4:00 Alexander Benaim 4:20 Andrea Caswell 4:40 Michael Connor 7:00 Faculty & Guest Readings: Benjamin Anastas and Mark Wunderlich 8:00 Historical Presentation: Lynne Sharon Schwartz: “Historic Recordings of Great 20th Century American Authors Reading their Work.” Deane Carriage Barn Saturday, June 17 Graduate Lectures 8:20 Ashley Olsen: “50 Shades of Consent: Sexual Desire and Sexual Violence in Contemporary Short Stories.” This lecture will examine tests from contemporary female authors including Mary Gaitskill, Margaret Atwood, and Roxane Gay. 9:00 Katie Pryor: “Persona & Violence in Ai’s Cruelty & Iliana Rocha’s Karankawa.” Both of these poets use persona poems to explore violence. What is powerful about this poetic device? How does the persona poem involve the reader and interrogate our notions of self? We’ll explore the connections and differences between these poets and their first books. 9:40 Karen Rile: “The Bad Writing Competition: Introducing Narrative Distance to Undergraduates.” A technique-centered workshop that offers coordinated readings and prompts can help beginning writers focus on discrete, achievable goals. But demonstrating smooth narrative distance shifts presents a practical challenge in an undergraduate workshop setting. The Bad Writing Competition, or mastery through parody, is a deft solution—with some unexpected ancillary benefits. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Ulating the American Man: Fear and Masculinity in the Post-9/11 American Superhero Film

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2011 Remas(k)ulating the American Man: Fear and Masculinity in the Post-9/11 American Superhero Film Carolyn P. Fisher College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Fisher, Carolyn P., "Remas(k)ulating the American Man: Fear and Masculinity in the Post-9/11 American Superhero Film" (2011). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 402. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/402 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Remas(k)ulating the American Man: Fear and Masculinity in the Post-9/11 American Superhero Film by Carolyn Fisher A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy from The College of William and Mary Accepted for _________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ______________________________________ Dr. Colleen Kennedy, Director ______________________________________ Dr. Frederick Corney ______________________________________ Dr. Arthur Knight Williamsburg, VA April 15, 2011 Fisher 1 Introduction Superheroes have served as sites for the reflection and shaping of American ideals and fears since they first appeared in comic book form in the 1930s. As popular icons which are meant to engage the American imagination and fulfill (however unrealistically) real American desires, they are able to inhabit an idealized and fantastical space in which these desires can be achieved and American enemies can be conquered. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Kirby: the Wonderthe Wonderyears Years Lee & Kirby: the Wonder Years (A.K.A

Kirby: The WonderThe WonderYears Years Lee & Kirby: The Wonder Years (a.k.a. Jack Kirby Collector #58) Written by Mark Alexander (1955-2011) Edited, designed, and proofread by John Morrow, publisher Softcover ISBN: 978-1-60549-038-0 First Printing • December 2011 • Printed in the USA The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. 18, No. 58, Winter 2011 (hey, it’s Dec. 3 as I type this!). Published quarterly by and ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. 919-449-0344. John Morrow, Editor/Publisher. Four-issue subscriptions: $50 US, $65 Canada, $72 elsewhere. Editorial package ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, a division of TwoMorrows Inc. All characters are trademarks of their respective companies. All artwork is ©2011 Jack Kirby Estate unless otherwise noted. Editorial matter ©2011 the respective authors. ISSN 1932-6912 Visit us on the web at: www.twomorrows.com • e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the publisher. (above and title page) Kirby pencils from What If? #11 (Oct. 1978). (opposite) Original Kirby collage for Fantastic Four #51, page 14. Acknowledgements First and foremost, thanks to my Aunt June for buying my first Marvel comic, and for everything else. Next, big thanks to my son Nicholas for endless research. From the age of three, the kid had the good taste to request the Marvel Masterworks for bedtime stories over Mother Goose. He still holds the record as the youngest contributor to The Jack Kirby Collector (see issue #21). Shout-out to my partners in rock ’n’ roll, the incomparable Hitmen—the best band and best pals I’ve ever had.